Power and Politics in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Teams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London Fall International Open 2015

Last Update: 10/12/2015 13:00 (UTC) Dublin, Edinburgh, Lisbon, London London Fall International Open 2015 WHITE / Juvenile / Male / Middle Carlson Gracie UK Byron Carlito Cox Dynamix Fighting Sports Daniel Alexander Persson Frota Team Matthew James Ball Pound for Pound José Maria Ferreira Mariz Ruivo Total: 4 WHITE / Juvenile / Female / Feather Brasa/99 Helima Nadheem Rahman Fight Move BJJ Charlyne Marzo Total: 2 WHITE / Juvenile / Female / Medium Heavy Dynamix Fighting Sports Karin Mika Brorsson Total: 1 WHITE / Adult / Male / Light Feather Batatinha Team Italia Gilberto Sitzia BJJ Globetrotters Terence Sibley Brigadeiro BJJ - UK Livio Dinaj Carlson Gracie UK Linas Mickevicius CheckMat International Anderson Gavioli Dos Santos CheckMat International Erick Da Silva Chiswick BJJ Artiom Bobko New School BJJ Lee Watts New School BJJ Romeo Carlo Pagulayan Oxford Shootfighter Paul Antonioni Ribeiro Jiu-Jitsu International Aaron Kane Ribeiro Jiu-Jitsu International Andrew Devlin Roger Gracie Joseph Moscardini Roger Gracie Academy Max Moscardini Total: 14 WHITE / Adult / Male / Feather Aeterna Jiu Jitsu Emanuele Fellico BJJ Academy LV - Pedro Sauer Team Aleksandrs Ruzga Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Team Malta Matthew Camilleri Brigadeiro BJJ - UK Harpreet Manku Carlson Gracie UK Henry Timson Carlson Gracie UK Samuel Forsythe CFS BJJ Alastair Henry CheckMat Ozan Kurtulus CheckMat International Olufemi Oshatogbe Dragon's Den Jaroslaw Sadowski Norwich BJJ Team Chrisostomos Hayes Norwich BJJ Team Jan Duplinszki Nova Uniao Europa Buttet Malik Nova Uniao Europa -

New York Spring International Open Jiu-Jitsu 2016 Final Results

Last Update: 04/10/2016 22:40 (UTC-05:00) Eastern Time (US & Canada) New York Spring International Open Jiu-Jitsu 2016 Final Results Academies Results Overall 1 - Ribeiro Jiu-Jitsu - 380 2 - Team Lloyd Irvin - 150 3 - Alliance Marcelo Garcia - 133 4 - Soul Fighters BJJ Connecticut - 109 5 - Renzo Gracie Academy - 108 6 - Gracie Barra - 95 7 - TAC Team BJJ - 87 8 - Nova União - 86 9 - SAS Team USA - 79 10 - Ground Control - 72 Athletes Results By Category WHITE / Adult / Male / Light Feather First - John Kim - Plus One Defense Systems Second - M. Andrew Heo - Ground Control Third - Barry Cheung Yee - Behring Puerto Rico Third - Henry Yengles Rodriguez - Capital Jiu-Jitsu WHITE / Adult / Male / Feather First - Shawn Arcelay - Carlson Gracie Team Second - Isaias Madeira - Renzo Gracie International Third - Roberson Lopez - SAS Team Third - Nicholas Pokoy - Ribeiro Jiu-Jitsu International WHITE / Adult / Male / Light First - Kyle Shaw - Workshop Second - Joseph Huggins - Ivey League Mixed Martial Arts Third - Joao Morselli - New England United BJJ Third - Tenzin Monlam - Ribeiro Jiu-Jitsu WHITE / Adult / Male / Middle First - Shane Kissinger - Ribeiro Jiu-Jitsu Second - Christian Macarilla - Team Robson Moura Third - Franc Korini - Ribeiro Jiu-Jitsu International WHITE / Adult / Male / Medium Heavy First - Ronald Tisdale - Team Jucão USA Second - Dennis Fliller - Soca BJJ Third - John Irving - Ribeiro Jiu-Jitsu Third - Wesley Rochelle - RMNU Team WHITE / Adult / Male / Heavy First - Tyler Welsh - Ribeiro Jiu-Jitsu Second - Gabriel Garcia -

Powerlifter to Bodybuilder: Matt Kroc Mark Bell Sits Down with Kroc to Get the Story Behind His Amazing Physique and His Journey Toward Becoming a Pro Bodybuilder

240SEP12_001-033.qxp 8/16/12 7:36 AM Page 1 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2012 SEP/OCT 2012 • VOL. 3, NO. 5 Content is copyright protected and provided for personal use only - not for reproduction or retransmission. For reprints please contact the Publisher. 240SEP12_001-033.qxp 8/16/12 7:36 AM Page 2 Content is copyright protected and provided for personal use only - not for reproduction or retransmission. For reprints please contact the Publisher. 240SEP12_001-033.qxp 8/16/12 7:36 AM Page 3 Content is copyright protected and provided for personal use only - not for reproduction or retransmission. For reprints please contact the Publisher. 240SEP12_001-033.qxp 8/16/12 7:36 AM Page 4 MAGAZINE VOLUME 3 • ISSUE 5 PUBLISHER Andee Bell POWER: YOUR WEAPON AGAINST WEAKNESS [email protected] EDITOR-AT-XTRA-LARGE ’m going to give myself a much needed pat on the back (if I can figure out how to reach it). Mark Bell • [email protected] For my wifey, the publisher, I’ll give her a much needed spank on the ass for yet another job Iwell done with Power. Yes, she gets spanked whether she’s good or bad. Also, not to brag, MANAGING EDITOR (OK here comes some bragging) but we are the only strength/powerlifting publication in the Heather Peavey world and we will continue to grow and expand. Power is devoted and honored to be your strength manual and your ultimate weapon against weakness! ASSOCIATE EDITOR I’d like to welcome a new addition to the Sling Shot family, Sam McDonald. -

First Name Last Name Age Class Belt Weight

First Name Last Name Age Class Belt Weight Class Academy / School Winter Nash 4-5 Years Old White-Grey Light-Feather Atlas Wyatt Bullock 4-5 Years Old White-Grey Feather Renzo Gracie Milford Academy Jandiel Garcia 4-5 Years Old White-Grey Feather Renzo Gracie Aca Gray Kachmar 4-5 Years Old White-Grey Feather ECU BJJ Liam Haughwout 4-5 Years Old White-Grey Middleweight Renzo Gracie Westchester Kieran Burke 6-7 Years Old White-Grey Feather Black Hole Jiu Jitsu ABIGAIL LUCERO 6-7 Years Old White-Grey Feather CARLSON GRACE TEAM-CT/CESAR PEREIRA BJJ Joshua Latham 6-7 Years Old White-Grey Feather Fit club thor souza 6-7 Years Old White-Grey Feather emerson souza bjj Dean Abdelkader 6-7 Years Old White-Grey Lightweight Emerson Souza Jayce Aviles 6-7 Years Old White-Grey Lightweight Vincent Gracie BJJ Isabelle Cornelius 6-7 Years Old White-Grey Lightweight Greenwich Jiu Jitsu Academy Liam Gatto 6-7 Years Old White-Grey Lightweight Cage JSA Wyatt Svendberg 6-7 Years Old White-Grey Lightweight TEAM BRIGHTMAN CARLSON GRACIE MMA & BRAZILIAN JIU JITSU Aristotelis Cimino 6-7 Years Old White-Grey Middleweight Soca BBJJ Rowan Falkson 6-7 Years Old White-Grey Middleweight Renzo Gracie Westchester Edwardo Guerrero 6-7 Years Old White-Grey Middleweight GF Connecticut Edwardo Guerrero-Garcia 6-7 Years Old White-Grey Middleweight GFTeam Connecticut Gabriella Musso 6-7 Years Old White-Grey Middleweight Endure Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Academy Landon Sigovitch 6-7 Years Old White-Grey Middleweight Renzo Gracie Milford Triton Cimino 6-7 Years Old White-Grey Light-Heavyweight -

Martial Arts from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia for Other Uses, See Martial Arts (Disambiguation)

Martial arts From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For other uses, see Martial arts (disambiguation). This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2011) Martial arts are extensive systems of codified practices and traditions of combat, practiced for a variety of reasons, including self-defense, competition, physical health and fitness, as well as mental and spiritual development. The term martial art has become heavily associated with the fighting arts of eastern Asia, but was originally used in regard to the combat systems of Europe as early as the 1550s. An English fencing manual of 1639 used the term in reference specifically to the "Science and Art" of swordplay. The term is ultimately derived from Latin, martial arts being the "Arts of Mars," the Roman god of war.[1] Some martial arts are considered 'traditional' and tied to an ethnic, cultural or religious background, while others are modern systems developed either by a founder or an association. Contents [hide] • 1 Variation and scope ○ 1.1 By technical focus ○ 1.2 By application or intent • 2 History ○ 2.1 Historical martial arts ○ 2.2 Folk styles ○ 2.3 Modern history • 3 Testing and competition ○ 3.1 Light- and medium-contact ○ 3.2 Full-contact ○ 3.3 Martial Sport • 4 Health and fitness benefits • 5 Self-defense, military and law enforcement applications • 6 Martial arts industry • 7 See also ○ 7.1 Equipment • 8 References • 9 External links [edit] Variation and scope Martial arts may be categorized along a variety of criteria, including: • Traditional or historical arts and contemporary styles of folk wrestling vs. -

Jun Fan Jeet Kune Do Terminology

THE SCIENCE OF FOOTWORK The JKD key to defeating any attack By: Ted Wong "The essence of fighting is the art of moving."- Bruce Lee Bruce Lee E-Paper - II Published by - The Wrong Brothers Click Here to Visit our Home page Email - [email protected] Jun Fan Jeet Kune Do Terminology Chinese Name English Translation 1) Lee Jun Fan Bruce Lee’s Chinese Name 2) Jeet Kune Do Way of the Intercepting Fist 3) Yu-Bay! Ready! 4) Gin Lai Salute 5) Bai Jong Ready Position 6) Kwoon School or Academy 7) Si-jo Founder of System (Bruce Lee) 8) Si-gung Your Instructor’s Instructor 9) Si-fu Your Instructor 10) Si-hing Your senior, older brother 11) Si-dai Your junior or younger brother 12) Si-bak Instructor’s senior 13) Si-sook Instructor’s junior 14) To-dai Student 15) Toe-suen Student’s Student 16) Phon-Sao Trapping Hands 17) Pak sao Slapping Hand 18) Lop sao Pulling Hand 19) Jut sao Jerking Hand 20) Jao sao Running Hand 21) Huen sao Circling Hand 22) Boang sao Deflecting Hand (elbow up) 23) Fook sao Horizontal Deflecting Arm 24) Maun sao Inquisitive Hand (Gum Sao) 25) Gum sao Covering, Pressing Hand, Forearm 26) Tan sao Palm Up Deflecting Hand 27) Ha pak Low Slap 28) Ouy ha pak Outside Low Slap Cover 29) Loy ha pak Inside Low Slap Cover 30) Ha o’ou sao Low Outside Hooking Hand 31) Woang pak High Cross Slap 32) Goang sao Low Outer Wrist Block 33) Ha da Low Hit 34) Jung da Middle Hit 35) Go da High Hit 36) Bil-Jee Thrusting fingers (finger jab) 37) Jik chung choi Straight Blast (Battle Punch) 38) Chung choi Vertical Fist 39) Gua choi Back Fist 40) -

A Glossary of Guards Part 1: the Closed Guard

Contents A Glossary of Guards Part 1: The Closed Guard ............... 3 Basic Closed Guard .......................................................................................4 High Guard ....................................................................................................5 Rubber Guard ................................................................................................6 Leghook Guard ..............................................................................................7 Shawn Williams Guard ..................................................................................8 A Glossary of Guards Part 2: The Open Guard .................. 9 Standard Open Guard ..................................................................................10 Spider Guard ...............................................................................................11 Butterfly Guard ...........................................................................................12 De la Riva Guard .........................................................................................13 Reverse de la Riva ......................................................................................14 Cross Guard ................................................................................................15 Sitting Open Guard ......................................................................................15 Grasshopper Guard .....................................................................................16 Upside -

Chicago Summer International Open 2014

Last Update: 08/08/2014 21:00 (UTC-06:00) Central Time (US & Canada) Chicago Summer International Open 2014 WHITE / Juvenile / Male / Middle Carlson Gracie Team John Brish Gracie Barra Allen Rinderle Gracie Barra Robert Rinderle Gracie Barra JJ Spencer Teplitz Total: 4 WHITE / Adult / Male / Light Feather Alliance Louis Verdera Andre Maneco BJJ Jeffrey Sanchez Brasa Justin Hallman Brasa Melvin Germino Carlson Gracie Team Joshua Liu Gracie Barra Zachary Pridemore McVicker's BJJ Andrew Hopple McVicker's BJJ Richard Cummings Valko BJJ Wilfred Mejia Total: 9 WHITE / Adult / Male / Feather Bonsai JJ - USA Adrian Kurzac Bonsai JJ - USA Horacio Rosiles Brasa Rohan Patel Carlson Gracie kyle barron Carlson Gracie Team Adam White Carlson Gracie Team Nathan Strening Clark Gracie Jiu Jitsu Academy Jeffrey Gotthardt Detroit Jiu-Jitsu Academy Jordon Sosa Gracie Barra Michael Sells Gracie Barra Mitchell Gaffney Gracie Barra JJ Davion Trotter Renato Tavares Association Aaron DeWitt Roufusport BJJ / Carlson Gracie Joshua Marsh Roufusport BJJ / Carlson Gracie Justin Chappelle Total: 14 WHITE / Adult / Male / Light Alliance Manuel Lara Andre Maneco BJJ Braulio Dominguez Bonsai JJ - USA Bryan Johnson Bonsai JJ - USA Tony Cruz Brasa Ashwin Kadaba Brasa Brian Herrera Brazil 021 International Nolan Mcguire Carlson Gracie daniel schapiro Carlson Gracie Team Jeremy Chavis Carlson Gracie Team Tony Garza Clark Gracie Jiu Jitsu Academy Nathan Boeve Clark Gracie Team International Brandon McNees Gracie Barra Kyle Wendt Gracie Barra Mahak Mukhi Gracie Elite Team America -

Master Instructor of Krav Maga Elite & Diamond Mixed Martial Arts

Master Instructor of Krav Maga Elite & Diamond Mixed Martial Arts: Joseph Diamond Joe Diamond is the Master Instructor of Krav Maga Elite and Diamond Mixed Martial Arts located in Northfield, NJ and Philadelphia, PA. Master Diamond is a licensed Real Estate salesperson currently working at Long and Foster in Ocean City, NJ. He is currently studying for the NJ Real Estate Broker’s exam. Master Diamond’s first experience with martial arts began when he trained at the Veteran’s Stadium with Kung Fu Expert and Phillies head trainer, Gus Hefling, alongside Phillies players: Mike Schmidt, Steve Carlton, Tug McGraw and John Vukovich, Master Diamond’s uncle. He continued his martial art training at the age of 12. He loved the workout and the confidence it gave him for protecting himself, family and friends. Upon achieving his Black Belt, he knew that Martial Arts would help develop a healthy lifestyle that made him stronger and confident. It became his passion to make it an essential part of his life. Master Diamond is a Level 3 US Army Combatives Instructor, and has taught Combatives and Brazilian Jiujitsu to enlisted and reserve soldiers for several years at Ft. Dix, NJ, Ft. Benning, GA, The Burlington Armory, NJ and ROTC Programs at local universities. Master Diamond is also a Level 5 Certified Instructor in Commando Krav Maga under Moni Aizik, world renowned Krav Maga expert. Master Diamond has taught law enforcement officers and military personnel from the following: New Jersey State Police, US Air Marshalls, FBI, US Army, US Marines, US Navy Seals and several local law enforcement agencies. -

San Diego 2017 San Diego - October 22 2016January 21 2017

Tap Cancer Out - San Diego 2017 San Diego - October 22 2016January 21 2017 TEAM RESULTS Only Top 10 Teams are listed. ADULT GI Academy Points 1 Gracie Humaita South Bay 54 2 Carlson Gracie Team Paul Silva 44 3 Clark Gracie 42 4 ATOS 40 5 The Stronghold 37 6 Apex Jiu Jitsu Bonita 33 7 Victory MMA 25 8 Carlson Gracie National City 21 9 Ocean Beach Brazilian Jiu Jitsu 19 10 The Arena 18 KIDS OVERALL (GI + NOGI) Academy Points 1 The Stronghold 70 2 Outliers 62 3 Gracie Humaita South Bay 59 4 Carlson Gracie National City 45 5 Nunez Jiu Jitsu 23 6 Clark Gracie 18 7 Apex Jiu Jitsu Bonita 17 8 Barum Jiu Jitsu 16 9 Alliance Jiu-Jitsu 15 10 HONU BJJ 14 OVERALL Academy Points 1 Gracie Humaita South Bay 113 2 The Stronghold 107 3 Outliers 77 4 Carlson Gracie National City 66 5 Clark Gracie 60 6 Carlson Gracie Team Paul Silva 56 7 Apex Jiu Jitsu Bonita 50 8 ATOS 40 9 Nunez Jiu Jitsu 34 10 Victory MMA 28 MATA LEAO - Martial Arts Tournament Management(www.mataleao.ca) 01/28/2017 4:46:51 PM Tap Cancer Out - San Diego 2017 San Diego - October 22 2016January 21 2017 GI DIVISIONS KIDS 1 OPEN - WHITE BELT GI - KIDS 1 OPEN - WHITE BELT - LIGHT FEATHER 1 Arianna Jade Yasay The Stronghold 2 Regan Cass fight lab GI - KIDS 1 OPEN - WHITE BELT - LIGHT 1 Nikolas Lacson The Stronghold 2 Easton Lyon San Diego Fight Club 3 Luis Palacio The Stronghold KIDS 2 OPEN - WHITE BELT GI - KIDS 2 OPEN - WHITE BELT - LIGHT FEATHER 1 Payton Patison Ramona BJJ 2 Evan Janus The Stronghold 3 Ivanna Espinosa Apex Jiu Jitsu Bonita GI - KIDS 2 OPEN - WHITE BELT - FEATHER 1 Troy Kovar -

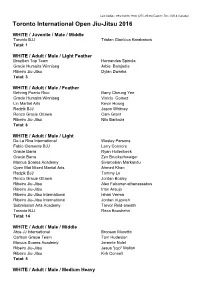

Toronto International Open Jiu-Jitsu 2016

Last Update: 09/23/2016 19:00 (UTC-05:00) Eastern Time (US & Canada) Toronto International Open Jiu-Jitsu 2016 WHITE / Juvenile / Male / Middle Toronto BJJ Tristan Gianluca Karabanow Total: 1 WHITE / Adult / Male / Light Feather Brazilian Top Team Hernandes Spinola Gracie Humaita Winnipeg Arbie Balajadia Ribeiro Jiu-Jitsu Dylan Dwarka Total: 3 WHITE / Adult / Male / Feather Behring Puerto Rico Barry Cheung Yee Gracie Humaita Winnipeg Vinicio Gomez Lin Martial Arts Kevin Hoang Radzik BJJ Jason Whitney Renzo Gracie Ottawa Cam Grant Ribeiro Jiu-Jitsu Nilo Barboza Total: 6 WHITE / Adult / Male / Light De La Riva International Wesley Parsons Fabio Clemente BJJ Larry Connors Gracie Barra Ryan Hollenbeck Gracie Barra Zen Bruckschwaiger Marcus Soares Academy Sivarooban Markandu Open Mat Mixed Martial Arts Ahmed Khan Radzik BJJ Tommy Le Renzo Gracie Ottawa Jordan Bosley Ribeiro Jiu-Jitsu Alex Falconer-athanassakos Ribeiro Jiu-Jitsu Irlan Araujo Ribeiro Jiu-Jitsu International Ishan Verma Ribeiro Jiu-Jitsu International Jordan Vujovich Submission Arts Academy Trevor Reid-sneath Toronto BJJ Reza Boushehri Total: 14 WHITE / Adult / Male / Middle Atos JJ International Bronson Morettin Carlson Gracie Team Tom Hudelson Marcus Soares Academy Jeremie Nolet Ribeiro Jiu-Jitsu Jesus "jojo" Mallari Ribeiro Jiu-Jitsu Kirk Connell Total: 5 WHITE / Adult / Male / Medium Heavy Action & Reaction Mixed Martial Arts Toronto Alex Green Body of Four Emile Perez Ribeiro Jiu-Jitsu Mason Foerter Ribeiro Jiu-Jitsu Shaun Mazzocca Ribeiro Jiu-Jitsu International Bryon Richards -

Sub League Qualifier 1 MEN's WHITE BELT

Sub League Qualifier 1 Saturday, April 20, 2019 Liberty High School, Hillsboro, Oregon Gi Results: Pages 1-12 No-Gi Results: Pages 13-18 2019 SUB LEAGUE QUALIFIER 1 TEAM RANKINGS 3 points for every 1st place* + 2 points for every 2nd place* + 1 point for every submission (excluding submissions earned in tie-breaker or bonus rounds) * No points were awarded in single competitor divisions or bonus rounds. 1st Impact Jiu Jitsu 6th CTA 2nd Renzo Gracie 7th Connection Rio Academy 3rd 10th Planet 8th Clark’s University of Martial Arts 4th Gracie Barra 9th Solid Base Grappling Academy 5th The Base 10th NWFA Sub League Season Team Champions are decided based on athletes’ cumulative performance over the entire season. MEN’S WHITE BELT White, Light Feather: 127.1 to 141.5 lbs. - Adult 1 Samuel Perry, Connection Rio Academy 2 Anthony Malang, Impact Jiu Jitsu 3 Tyler Hioe, Adamson Bros White, Light Feather: 127.1 to 141.5 lbs. - Master 1 1 Eric Farley, Impact Jiu Jitsu - Beaverton 2 Michael Beck, The Base White, Feather: 141.6 to 154.5 lbs. - Adult 1 Trayton Enick, Solid Base Grappling Academy 2 Kyle Augur, Gracie Technics 3 Justin Murray, Zenith/Next Level 4 Nicholas Mercado, Impact Jiu Jitsu - Hillsboro 5 Miguel Sales, Gracie Technics Troutdale White, Feather: 141.6 to 154.5 lbs. - Master 1 1 Henry Obelnicki, Renzo Gracie PDX 2 Robert Campisi, Connection Rio Academy 3 Fred Coletta, Connection Rio Academy 3 William Searles, Zenith/Next Level 4 Andy Nguyen, Impact Jiu Jitsu subleague.com Page 1 of 18 White, Light: 154.6 to 168.0 lbs.