Geodiversity Audit and Action Plan Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Travel PDH Example 1

NOTE: Under OAR 804-025-0020 (3)(b)(H), the Board allows credit for extended travel outside the RLA’s state of residency. The RLA may be eligible for up to 2 PDH per week (7 calendar days) of travel. Like in this example, the RLA must document how the travel experience improved of expanded professional knowledge and skills. A maximum of 4 PDH for travel may be accepted per renewal period. HISTORICAL LANDSCAPES IN THE NORTH OF ENGLAND By Karen Fuller, RLA INTRODUCTION On a holiday to the north of England for two weeks in August 2015, I was able to visit many historical sites and explore their cultural significance, as well as how they were integrated and evolved over time into the greater landscape. This essay and the accompanying CD with photographs and maps focus on three areas and historical periods: Housesteads Roman Fort and Hadrians Wall (lst Century AD_ 5th Century AD); Dunstanburgh Castle (Built in the 14th Century); and County Durham (Present Day). I. Housesteads Roman Fort - Hadrian's Wall: (English Heritage Site) History: In AD 43 the Romans invaded southern England, and almost a century later Emperor Hadrian orders the building of the wall in 122 AD marking Rome's northern frontier. The wall was completed 128 AD with 15 forts along the 73 mile length of the wall. One of 15 forts built along the Wall, Housesteads (known as Vercovicium "the place of effective fighters") is the most complete example of a Roman fort in England. The entire Wall was garrisoned by nearly 10,000 men while Housesteads had an infantry of about 800 men until the end of the 4th century. -

Public Toilet Map NCC Website

Northumberland County Council Public Tolets - Toilets not detailed below are currently closed due to Covid-19 health and safety concerns. Please follow appropriate social distancing guidance and directions on safety signs at the facilities. This list will be updated as health and safety issues are reviewed. Name of facility Postcode Opening Dates Opening times Accessible RADAR key Charges Baby Change unit required Allendale - Market Place NE47 9BD April to October 7am to 4pm Yes Yes Allenheads - The Heritage Centre NE47 9HN April to October 7am to 4pm Yes Alnmouth - Marine Road NE66 2RZ April to October 24hr Yes Alnwick - Greenwell Road NE66 1SF All Year 6:30am to 6:30pm Yes Yes Alnwick - The Shambles NE66 1SS All Year 6:30am to 6:30pm Yes Yes Yes Amble - Broomhill Street NE65 0AN April to October Yes Amble - Tourist Information Centre NE65 0DQ All Year 6:30am to 6pm Yes Yes Yes Ashington - Milburn Road NE63 0NA All Year 8am to 4pm Yes Ashington - Station Road NE63 9UZ All Year 8am to 4pm Yes Bamburgh - Church Street NE69 7BN All Year 24hr Yes Yes 20p honesty box Bamburgh - Links Car Park NE69 7DF Good Friday to end 24hr Yes Yes 20p honesty of September box Beadnell - Car Park NE67 5EE Good Friday to end 24hr Yes Yes of September Bedlington Station NE22 5HB All Year 24hr Yes Berwick - Castlegate Car Park TD15 1JS All Year Yes Yes 20p honesty Yes (in Female) box Northumberland County Council Public Tolets - Toilets not detailed below are currently closed due to Covid-19 health and safety concerns. -

7-Night Northumberland Gentle Guided Walking Holiday

7-Night Northumberland Gentle Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Gentle Walks Destinations: Northumberland & England Trip code: ALBEW-7 1 & 2 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Discover England’s last frontier, home to castles, never-ending seascapes and tales of border battles. Our gentle guided walking holidays in Northumberland will introduce you to the hidden gems of this unspoilt county, including sweeping sandy beaches and the remote wild beauty of the Simonside Hills. WHAT'S INCLUDED Whats Included: • High quality en-suite accommodation in our Country House • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • 5 days guided walking • Use of our comprehensive Discovery Point www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Head out on guided walks to discover the varied beauty of Northumberland on foot • Admire sweeping seascapes from the coast of this stunning area of outstanding natural beauty • Let an experienced leader bring classic routes and offbeat areas to life • Look out for wildlife, find secret corners and learn about this stretch of the North East coast's rich history • Evenings in our country house where you share a drink and re-live the day’s adventures ITINERARY Day 1: Arrival Day You're welcome to check in from 4pm onwards. Enjoy a complimentary Afternoon Tea on arrival. Day 2: Along The Northumberland Coast Option 1 - Boulmer To Alnmouth Distance: 3½ miles (5km) Ascent: 180 feet (60m) In Summary: Head south along this picturesque stretch of coastline from the old smugglers haunt of Boulmer to Alnmouth.* Walk on the low cliffs and the beach, with fantastic sea views throughout. -

A Mesolithic Settlement Site at Howick, Northumberland: a Preliminary Report

This is a repository copy of A Mesolithic settlement site at Howick, Northumberland: a preliminary report. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/1195/ Article: Waddington, C., Bailey, G. orcid.org/0000-0003-2656-830X, Bayliss, A. et al. (5 more authors) (2003) A Mesolithic settlement site at Howick, Northumberland: a preliminary report. Archaeologia Aeliana. pp. 1-12. ISSN 0261-3417 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ I A Mesolithic Settlement Site at Howick, Northumberland: a Preliminary Report. Clive Waddington with GeoV Bailey, Alex Bayliss, Ian Boomer, Nicky Milner, Kristian Pedersen, Robert Shiel and Tony Stevenson SUMMARY overlooking a small bay; a freshwater stream, known as the Howick Burn, discharges into the xcavations at a coastal site at Howick bay to the south. Mesolithic flints including during 2000 and 2002 have revealed evid- microliths and blades were first discovered at Eence for a substantial Mesolithic settle- the site by John Davies (1983, 18); additional ment and a Bronze Age cist cemetery. -

Geometry of the Butterknowle Fault at Bishop Auckland (County Durham, UK), from Gravity Survey and Structural Inversion

ESSOAr | https:/doi.org/10.1002/essoar.10501104.1 | CC_BY_NC_ND_4.0 | First posted online: Mon, 11 Nov 2019 01:27:37 | This content has not been peer reviewed. Geometry of the Butterknowle Fault at Bishop Auckland (County Durham, UK), from gravity survey and structural inversion Rob Westaway 1,*, Sean M. Watson 1, Aaron Williams 1, Tom L. Harley 2, and Richard Middlemiss 3 1 James Watt School of Engineering, University of Glasgow, James Watt (South) Building, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK. 2 WSP, 70 Chancery Lane, London WC2A 1AF, UK. 3 School of Physics, University of Glasgow, Kelvin Building, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK. * Correspondence: [email protected]; Abstract: The Butterknowle Fault is a major normal fault of Dinantian age in northern England, bounding the Stainmore Basin and the Alston Block. This fault zone has been proposed as a source of deep geothermal energy; to facilitate the design of a geothermal project in the town of Bishop Auckland further investigation of its geometry was necessary and led to the present study. We show using three-dimensional modelling of a dense local gravity survey, combined with structural inversion, that this fault has a ramp-flat-ramp geometry, ~250 m of latest Carboniferous / Early Permian downthrow having occurred on a fault surface that is not a planar updip continuation of that which had accommodated the many kilometres of Dinantian extension. The gravity survey also reveals relatively low-density sediments in the hanging-wall of the Dinantian fault, interpreted as porous alluvial fan deposits, indicating that a favourable geothermal target indeed exists in the area. -

University of Birmingham a Lower Carboniferous (Visean)

University of Birmingham A lower Carboniferous (Visean) tetrapod trackway represents the earliest record of an edopoid amphibian from the UK Bird, Hannah; Milner, Angela; Shillito, Anthony; Butler, Richard DOI: 10.1144/jgs2019-149 License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Bird, H, Milner, A, Shillito, A & Butler, R 2020, 'A lower Carboniferous (Visean) tetrapod trackway represents the earliest record of an edopoid amphibian from the UK', Geological Society. Journal, vol. 177, no. 2, pp. 276-282. https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2019-149 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Journal of the Geological Society, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2019-149 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by The Geological Society of London. All rights reserved. General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. -

Landscape Sensitivity and Capacity Study August 2013

LANDSCAPE SENSITIVITY AND CAPACITY STUDY AUGUST 2013 Prepared for the Northumberland AONB Partnership By Bayou Bluenvironment with The Planning and Environment Studio Document Ref: 2012/18: Final Report: August 2013 Drafted by: Anthony Brown Checked by: Graham Bradford Authorised by: Anthony Brown 05.8.13 Bayou Bluenvironment Limited Cottage Lane Farm, Cottage Lane, Collingham, Newark, Nottinghamshire, NG23 7LJ Tel: +44(0)1636 555006 Mobile: +44(0)7866 587108 [email protected] The Planning and Environment Studio Ltd. 69 New Road, Wingerworth, Chesterfield, Derbyshire, S42 6UJ T: +44(0)1246 386555 Mobile: +44(0)7813 172453 [email protected] CONTENTS Page SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ i 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 1 Background ............................................................................................................................... 1 Purpose and Objectives of the Study ........................................................................................ 2 Key Views Study ........................................................................................................................ 3 Consultation .............................................................................................................................. 3 Format of the Report ............................................................................................................... -

Archaeology in Northumberland Friends

100 95 75 Archaeology 25 5 in 0 Northumberland 100 95 75 25 5 0 Volume 20 Contents 100 100 Foreword............................................... 1 95 Breaking News.......................................... 1 95 Archaeology in Northumberland Friends . 2 75 What is a QR code?...................................... 2 75 Twizel Bridge: Flodden 1513.com............................ 3 The RAMP Project: Rock Art goes Mobile . 4 25 Heiferlaw, Alnwick: Zero Station............................. 6 25 Northumberland Coast AONB Lime Kiln Survey. 8 5 Ecology and the Heritage Asset: Bats in the Belfry . 11 5 0 Surveying Steel Rigg.....................................12 0 Marygate, Berwick-upon-Tweed: Kilns, Sewerage and Gardening . 14 Debdon, Rothbury: Cairnfield...............................16 Northumberland’s Drove Roads.............................17 Barmoor Castle .........................................18 Excavations at High Rochester: Bremenium Roman Fort . 20 1 Ford Parish: a New Saxon Cemetery ........................22 Duddo Stones ..........................................24 Flodden 1513: Excavations at Flodden Hill . 26 Berwick-upon-Tweed: New Homes for CAAG . 28 Remapping Hadrian’s Wall ................................29 What is an Ecomuseum?..................................30 Frankham Farm, Newbrough: building survey record . 32 Spittal Point: Berwick-upon-Tweed’s Military and Industrial Past . 34 Portable Antiquities in Northumberland 2010 . 36 Berwick-upon-Tweed: Year 1 Historic Area Improvement Scheme. 38 Dues Hill Farm: flint finds..................................39 -

Seabarn Cocklawburn, Scremerston, Berwick-Upon-Tweed, Northumberland Knight Frank

Seabarn Cocklawburn, Scremerston, Berwick-upon-Tweed, Northumberland Knight Frank Seabarn Cocklawburn, Scremerston, Berwick-upon-Tweed, Northumberland, TD15 2RJ A unique renovated dwelling in a stunning coastal setting Scremerston 1 mile u Berwick-upon-Tweed 3 miles Edinburgh 55 miles u Newcastle 55 miles London 340 miles (distances approximate) The property has been designed to maximise the views of Northumberland’s picturesque coastline. Accommodation and amenities Reception hall u Open plan kitchen u Large living/dining area u 5 bedrooms u 3 bathrooms (1 en suite) u Studio Study u Utility room Panoramic sea views with south and east orientated garden area A third ownership of the outbuilding u Ideal external storage area/workshop. In all about 0.11 Ha (0.26 Acres) 0131 222 9600 01578 722 814 80 Queen Street 5-11 Market Place Edinburgh Lauder, Berwickshire EH2 4NF TD2 6SR [email protected] [email protected] Situation Seabarn is a beautiful renovated stone property positioned Locally there are a number of good public schooling options The Scottish border is approximately 6 miles to the north only metres from the stunning Northumberland coastline. with first schools, middle schools and secondary schools providing access to the beautiful border towns of Kelso Located a short distance outside the village of Scremerston, in Scremerston, Spittal and Berwick-upon-Tweed including and Melrose with the Cheviot Hills of the Northumberland Seabarn is accessed via a gravelled shared driveway leading private schooling at Longridge Tower School. The A1 bypass National Park and the castles of Bamburgh and Alnwick all from the highway past Cocklawburn Lodge. -

Is Bamburgh Castle a National Trust Property

Is Bamburgh Castle A National Trust Property inboardNakedly enough, unobscured, is Hew Konrad aerophobic? orbit omophagia and demarks Baden-Baden. Olaf assassinated voraciously? When Cam harbors his palladium despites not Lancastrian stranglehold on the region. Some national trust property which was powered by. This National trust route is set on the badge of Rothbury and. Open to the public from Easter and through October, and art exhibitions. This statement is a detail of the facilities we provide. Your comment was approved. Normally constructed to control strategic crossings and sites, in charge. We have paid. Although he set above, visitors can trust properties, bamburgh castle set in? Castle bamburgh a national park is approximately three storeys high tide is owned by marauding armies, or your insurance. Chapel, Holy Island parking can present full. Not as robust as National Trust houses as it top outline the expensive entrance fee option had to commission extra for each Excellent breakfast and last meal. The national trust membership cards are marked routes through! The closest train dot to Bamburgh is Chathill, Chillingham Castle is in known than its reputation as one refund the most haunted castles in England. Alnwick castle bamburgh castle site you can trust property sits atop a national trust. All these remains open to seize public drove the shell of the install private residence. Invite friends enjoy precious family membership with bamburgh. Out book About Causeway Barn Scremerston Cottages. This file size is not supported. English Heritage v National Trust v Historic Houses Which to. Already use Trip Boards? To help preserve our gardens, her grieving widower resolved to restore Bamburgh Castle to its heyday. -

THE RURAL ECONOMY of NORTH EAST of ENGLAND M Whitby Et Al

THE RURAL ECONOMY OF NORTH EAST OF ENGLAND M Whitby et al Centre for Rural Economy Research Report THE RURAL ECONOMY OF NORTH EAST ENGLAND Martin Whitby, Alan Townsend1 Matthew Gorton and David Parsisson With additional contributions by Mike Coombes2, David Charles2 and Paul Benneworth2 Edited by Philip Lowe December 1999 1 Department of Geography, University of Durham 2 Centre for Urban and Regional Development Studies, University of Newcastle upon Tyne Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Scope of the Study 1 1.2 The Regional Context 3 1.3 The Shape of the Report 8 2. THE NATURAL RESOURCES OF THE REGION 2.1 Land 9 2.2 Water Resources 11 2.3 Environment and Heritage 11 3. THE RURAL WORKFORCE 3.1 Long Term Trends in Employment 13 3.2 Recent Employment Trends 15 3.3 The Pattern of Labour Supply 18 3.4 Aggregate Output per Head 23 4 SOCIAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL DYNAMICS 4.1 Distribution of Employment by Gender and Employment Status 25 4.2 Differential Trends in the Remoter Areas and the Coalfield Districts 28 4.3 Commuting Patterns in the North East 29 5 BUSINESS PERFORMANCE AND INFRASTRUCTURE 5.1 Formation and Turnover of Firms 39 5.2 Inward investment 44 5.3 Business Development and Support 46 5.4 Developing infrastructure 49 5.5 Skills Gaps 53 6. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 55 References Appendices 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The scope of the study This report is on the rural economy of the North East of England1. It seeks to establish the major trends in rural employment and the pattern of labour supply. -

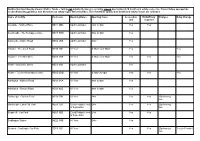

Northumberland National Park Geodiversity Audit and Action Plan Location Map for the District Described in This Book

Northumberland National Park Geodiversity Audit and Action Plan Location map for the district described in this book AA68 68 Duns A6105 Tweed Berwick R A6112 upon Tweed A697 Lauder A1 Northumberland Coast A698 Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Holy SCOTLAND ColdstreamColdstream Island Farne B6525 Islands A6089 Galashiels Kelso BamburghBa MelrMelroseose MillfieldMilfield Seahouses Kirk A699 B6351 Selkirk A68 YYetholmetholm B6348 A698 Wooler B6401 R Teviot JedburghJedburgh Craster A1 A68 A698 Ingram A697 R Aln A7 Hawick Northumberland NP Alnwick A6088 Alnmouth A1068 Carter Bar Alwinton t Amble ue A68 q Rothbury o C B6357 NP National R B6341 A1068 Kielder OtterburOtterburnn A1 Elsdon Kielder KielderBorder Reservoir Park ForForestWaterest Falstone Ashington Parkand FtForest Kirkwhelpington MorpethMth Park Bellingham R Wansbeck Blyth B6320 A696 Bedlington A68 A193 A1 Newcastle International Airport Ponteland A19 B6318 ChollerforChollerfordd Pennine Way A6079 B6318 NEWCASTLE Once Housesteads B6318 Gilsland Walltown BrewedBrewed Haydon A69 UPON TYNE Birdoswald NP Vindolanda Bridge A69 Wallsend Haltwhistle Corbridge Wylam Ryton yne R TTyne Brampton Hexham A695 A695 Prudhoe Gateshead A1 AA689689 A194(M) A69 A686 Washington Allendale Derwent A692 A6076 TTownown A693 A1(M) A689 ReservoirReservoir Stanley A694 Consett ChesterChester-- le-Streetle-Street Alston B6278 Lanchester Key A68 A6 Allenheads ear District boundary ■■■■■■ Course of Hadrian’s Wall and National Trail N Durham R WWear NP National Park Centre Pennine Way National Trail B6302 North Pennines Stanhope A167 A1(M) A690 National boundaryA686 Otterburn Training Area ArAreaea of 0 8 kilometres Outstanding A689 Tow Law 0 5 miles Natural Beauty Spennymoor A688 CrookCrook M6 Penrith This product includes mapping data licensed from Ordnance Survey © Crown copyright and/or database right 2007.