Song, Protest, the University, and the Nation: Delhi, 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Star Campaigners of Lndian National Congress for West Benqal

, ph .230184s2 $ t./r. --g-tv ' "''23019080 INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 24, AKBAR ROAD, NEW DELHI'110011 K.C VENUGOPAL, MP General Secretary PG-gC/ }:B U 12th March,2021 The Secretary Election Commission of lndia Nirvachan Sadan New Delhi *e Sub: Star Campaigners of lndian National Congress for West Benqal. 2 Sir, The following leaders of lndian National Congress, who would be campaigning as per Section 77(1) of Representation of People Act 1951, for the ensuing First Phase '7* of elections to the Legislative Assembly of West Bengat to be held on 2ffif M-arch br,*r% 2021. \,/ Sl.No. Campaiqners Sl.No. Campaiqners \ 1 Smt. Sonia Gandhi 16 Shri R"P.N. Sinqh 2 Dr. Manmohan Sinqh 17 Shri Naviot Sinqh Sidhu 3 Shri Rahul Gandhi 18 ShriAbdul Mannan 4 Smt. Priyanka Gandhi Vadra 19 Shri Pradip Bhattacharva w 5 Shri Mallikarjun Kharqe 20 Smt. Deepa Dasmunsi 6 ShriAshok Gehlot 21 Shri A.H. Khan Choudhary ,n.T 7 Capt. Amarinder Sinqh 22 ShriAbhiiit Mukheriee 8 Shri Bhupesh Bhaohel 23 Shri Deependra Hooda * I Shri Kamal Nath 24 Shri Akhilesh Prasad Sinqh 10 Shri Adhir Ranian Chowdhury 25 Shri Rameshwar Oraon 11 Shri B.K. Hari Prasad 26 Shri Alamqir Alam 12 Shri Salman Khurshid 27 Mohd Azharuddin '13 Shri Sachin Pilot 28 Shri Jaiveer Sherqill 14 Shri Randeep Singh Suriewala 29 Shri Pawan Khera 15 Shri Jitin Prasada 30 Shri B.P. Sinqh This is for your kind perusal and necessary action. Thanking you, Yours faithfully, IIt' I \..- l- ;i.( ..-1 )7 ,. " : si fqdq I-,. elS€ (K.C4fENUGOPAL) I t", j =\ - ,i 3o Os 'Ji:.:l{i:,iii-iliii..d'a !:.i1.ii'ji':,1 s}T ji}'iE;i:"]" tiiaA;i:i:ii-q;T') ilem€s"m} il*Eaacr:lltt,*e Ge rt r; l-;a. -

Global Digital Cultures: Perspectives from South Asia

Revised Pages Global Digital Cultures Revised Pages Revised Pages Global Digital Cultures Perspectives from South Asia ASWIN PUNATHAMBEKAR AND SRIRAM MOHAN, EDITORS UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS • ANN ARBOR Revised Pages Copyright © 2019 by Aswin Punathambekar and Sriram Mohan All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid- free paper First published June 2019 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication data has been applied for. ISBN: 978- 0- 472- 13140- 2 (Hardcover : alk paper) ISBN: 978- 0- 472- 12531- 9 (ebook) Revised Pages Acknowledgments The idea for this book emerged from conversations that took place among some of the authors at a conference on “Digital South Asia” at the Univer- sity of Michigan’s Center for South Asian Studies. At the conference, there was a collective recognition of the unfolding impact of digitalization on various aspects of social, cultural, and political life in South Asia. We had a keen sense of how much things had changed in the South Asian mediascape since the introduction of cable and satellite television in the late 1980s and early 1990s. We were also aware of the growing interest in media studies within South Asian studies, and hoped that the conference would resonate with scholars from various disciplines across the humanities and social sci- ences. -

The Radical Humanist on Website

Articles and Features: Present Social Scenario In our country there is continuous fall in the economic or standard of all democratic institutions. administrative, one Particularly the increasing criminalization among finds that it is political life of India where known criminals are enveloped in gloom, elected and become members of apex political frustration (Late Ramesh Korde institutions called parliament and also of V.M.Tarkunde). provincial legislative assemblies that administer At present as reported, nearly more than all the aspects of country. This has resulted into about thirty percent population live below enormous rise in administrative corruption. poverty line with million unemployed or semi- Present scenario presents criminals and employed and at the same time rapid growth of anti-social elements have been gaining population aggravating both poverty and acceptability in social and political area. It is unemployment. The result is, Indian democracy reported that in several parts of our country is and invariably continue to be weak, shaky where mafia leaders have become political and unstable. bosses. This has led to enormous increase of The present prevailing economic, social, administrative corruption by leaps and bounds. cultural inequalities, democracy is confined to It has become all pervasive and threatens to political sphere in not likely to continue in India become way of life so that it does not evoke for long time and will not lead to deeper and any moral revulsion. moral meaningful democracy. Even though civil liberties are guaranteed by In India political parties are involved in our constitution, however in present prevailing unprincipled struggle for power that has political and economic situation where only divorced moral principle from political practice. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Indian student protests and the nationalist–neoliberal nexus Journal Item How to cite: Gupta, Suman (2019). Indian student protests and the nationalist–neoliberal nexus. Postcolonial Studies, 22(1) pp. 1–15. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2019 The Institute of Postcolonial Studies Version: Accepted Manuscript Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1080/13688790.2019.1568163 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Postcolonial Studies Vol. 22 Issue 1, 2019, Print ISSN: 1368-8790 Online ISSN: 1466- 1888 Accepted, pre-copy edited version Indian Student Protests and the Nationalist-Neoliberal Nexus Suman Gupta Professor of Literature and Cultural History / Head of the Department of English and Creative Writing, The Open University UK [email protected] Abstract: This paper discusses the wider relevance of recent, 2014 and onwards, student protests in Indian higher education institutions, with the global neoliberal reorganisation of the sector in mind. The argument is tracked from specific high-profile junctures of student protests toward their grounding in the national/state level situation and then their ultimate bearing on the prevailing global condition. In particular, this paper considers present-day management practices and their relationship with projects to embed conservative and authoritarian norms in the higher education sector. -

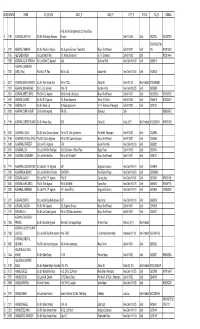

Main Voter List 08.01.2018.Pdf

Sl.NO ADM.NO NAME SO_DO_WO ADD1_R ADD2_R CITY_R STATE TEL_R MOBILE 61-B, Abul Fazal Apartments 22, Vasundhara 1 1150 ACHARJEE,AMITAVA S/o Shri Sudhamay Acharjee Enclave Delhi-110 096 Delhi 22620723 9312282751 22752142,22794 2 0181 ADHYARU,YASHANK S/o Shri Pravin K. Adhyaru 295, Supreme Enclave, Tower No.3, Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 745 9810813583 3 0155 AELTEMESH REIN S/o Late Shri M. Rein 107, Natraj Apartments 67, I.P. Extension Delhi-110 092 Delhi 9810214464 4 1298 AGARWAL,ALOK KRISHNA S/o Late Shri K.C. Agarwal A-56, Gulmohar Park New Delhi-110 049 Delhi 26851313 AGARWAL,DARSHANA 5 1337 (MRS.) (Faizi) W/o Shri O.P. Faizi Flat No. 258, Kailash Hills New Delhi-110 065 Delhi 51621300 6 0317 AGARWAL,MAM CHANDRA S/o Shri Ram Sharan Das Flat No.1133, Sector-29, Noida-201 301 Uttar Pradesh 0120-2453952 7 1427 AGARWAL,MOHAN BABU S/o Dr. C.B. Agarwal H.No. 78, Sukhdev Vihar New Delhi-110 025 Delhi 26919586 8 1021 AGARWAL,NEETA (MRS.) W/o Shri K.C. Agarwal B-608, Anand Lok Society Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 9312059240 9810139122 9 0687 AGARWAL,RAJEEV S/o Shri R.C. Agarwal 244, Bharat Apartment Sector-13, Rohini Delhi-110 085 Delhi 27554674 9810028877 11 1400 AGARWAL,S.K. S/o Shri Kishan Lal 78, Kirpal Apartments 44, I.P. Extension, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22721132 12 0933 AGARWAL,SUNIL KUMAR S/o Murlidhar Agarwal WB-106, Shakarpur, Delhi 9868036752 13 1199 AGARWAL,SURESH KUMAR S/o Shri Narain Dass B-28, Sector-53 Noida, (UP) Uttar Pradesh0120-2583477 9818791243 15 0242 AGGARWAL,ARUN S/o Shri Uma Shankar Agarwal Flat No.26, Trilok Apartments Plot No.85, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22433988 16 0194 AGGARWAL,MRIDUL (MRS.) W/o Shri Rajesh Aggarwal Flat No.214, Supreme Enclave Mayur Vihar Phase-I, Delhi-110 091 Delhi 22795565 17 0484 AGGARWAL,PRADEEP S/o Late R.P. -

Reuters Institute Fellowship Paper University of Oxford

1 Reuters Institute Fellowship Paper University of Oxford IN NEED OF A LEVESON? JOURNALISM IN INDIA IN TIMES OF 1 PAID NEWS AND ‘PRIVATE TREATIES’ By Anuradha Sharma2 Hilary & Trinity 2013 Sponsor: Thomson Reuters Foundation ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1 I take part of my title from Arghya Sengupta’s article “Does India need its Leveson?” Free Speech Debate website, May 13, 2013, http://freespeechdebate.com/en/discuss/does-india-need-its-leveson/ 2 Anuradha Sharma was a journalist fellow at the Reuters Institute in 2013. She worked at the Economic Times from July 2008 to January 2011. She is now a freelance journalist writing on politics and culture in South Asia. 2 To the Reuters Institute, I am grateful for selecting me for the programme. To the Thomson Reuters Foundation, I shall always remain indebted for being my sponsor, and for making this experience possible for me. Supervision by John Lloyd was a sheer privilege. My heartfelt gratitude goes to John for being a wonderful guide, always ready with help and advice, and never once losing patience with my fickle thoughts. Thank you, James Painter for all the inputs, comments and questions that helped me to shape my research paper. Dr. David Levy and. Tim Suter‘s contributions to my research were invaluable. Prof. Robert Picard‘s inputs on global media businesses and observations on ―private treaties‖ were crucial. My heartfelt thanks also go to Alex, Rebecca, Kate, Tanya and Sara for taking care of every small detail that made my Oxford experience memorable and my research enriching. To the other fellows I shall remain indebted for the gainful exchanges and fun I had in Oxford. -

Pss Files Songs Acknowledgements in “Photostage

[Type(Mr) here] Soman RAGAVAN. www.somanragavan.org PSS-02. Songs acknowledgements in “Photostage” Slideshows. 2 June, 2021. Placed on website. Mauritius. SONGS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS IN “PHOTOSTAGE” SLIDESHOWS PSS FILES ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS : ➢ Song : “Tumko Dekha To” ➢ From the film : “Saath Saath,” 1982 ➢ Singers : Jagjit Singh; Chitra Singh ➢ Director : Raman Kumar ➢ Producer : Dilip Dhawan ➢ Music : Kuldeep Singh ➢ Lyricist : ➢ Cinematography : Sunil Sharma + other rights holders + photos from the Internet ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- PSS-10 - SR life --Page 1 of 10 -- [Type(Mr) here] Soman RAGAVAN. www.somanragavan.org PSS-02. Songs acknowledgements in “Photostage” Slideshows. 2 June, 2021. Placed on website. Mauritius. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS See file PSS-00. No copyright infringements intended. *Song : “Ye safar” *From the film : “1942 A Love Story,” 1994 *Singer : S. Chattopadhyay *Director : V. V. Chopra *Producer : V. V. Chopra *Music : R. D. Burman *Lyricist : J. Akthar *Cinematography : B. Pradhan + other rights holders + photos from the Internet PSS-11 www.somanragavan.org --Page 2 of 10 -- [Type(Mr) here] Soman RAGAVAN. www.somanragavan.org PSS-02. Songs acknowledgements in “Photostage” Slideshows. 2 June, 2021. Placed on website. Mauritius. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ➢ See file PSS-00. No copyright infringements intended. ➢ Song : “Tumko dekha to” ➢ From the film : “Hamara dil aap ke paas,” 2000 ➢ Singers : Kumar Sanu; Alka Yagnik ➢ Director : S. Kaushik ➢ Producers : S. Kapoor; B. Kapoor ➢ Music : Sanjeev-Darshan ➢ Lyricist : ➢ Cinematography : K. Lal ➢ other rights holders ➢ photos from the Internet PSS-12 www.somanragavan.org ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- --Page 3 of 10 -- [Type(Mr) here] Soman RAGAVAN. www.somanragavan.org PSS-02. Songs acknowledgements in “Photostage” Slideshows. 2 June, 2021. Placed on website. Mauritius. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS See file PSS-00. No copyright infringements intended. -

Where Is This Self-Proclaimed Nationalism Coming From?

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Where is this Self-Proclaimed Nationalism Coming From? Kanhaiya Kumar's Speech in JNU KANHAIYA KUMAR Vol. 51, Issue No. 10, 05 Mar, 2016 Kanhaiya Kumar is the president of the Jawaharlal Nehru University Students Union (JNUSU). He was arrested on 13 February 2016 on charges of sedition and was granted a six-month interim bail on 2 March by the Delhi High Court. Jawaharlal Nehru University Students Union President Kanhaiya Kumar gave a speech in JNU after he was released from judicial custody on being granted a six month interim bail by the Delhi High Court. We reproduce an English translation of sections of his Hindi speech. From this platform on behalf of all of you, as JUNUSU president I take this opportunity of the media’s presence to thank and salute the people of this country. I want to thank all the people across the world, academicians and students, who have stood with JNU. I salute them (lal salaam). I have no rancour against anyone – none whatsoever against the ABVP [Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad, student wing of the BJP]. You know why? (crowd roars – why?) Because the ABVP on our campus is actually more rational than the ABVP outside the campus. I have one suggestion for all those people who consider themselves political pundits – kindly watch the recording of the last presidential debate to see the state the ABVP candidate was reduced to. When we decimated the sharpest ABVP intellect there is in the country, which happens to be in the ABVP of JNU, you can draw your own conclusions about what awaits you in the rest of the country. -

Urgent Action

UA: 49/16 Index: ASA 20/3578/2016 India Date: 4 March 2016 URGENT ACTION PROFESSOR AND STUDENTS DETAINED FOR SEDITION A professor from Delhi University and two students from the Jawaharlal University (JNU) in Delhi are in detention for allegedly chanting ‘anti-India’ slogans at two separate events. If convicted, they could face a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. Another student arrested on suspicion of the same offence has been released on bail. According to the Delhi police’s First Information Report (FIR) against Syed Abdul Rehman Geelani, a television news report on 11 February highlighted an event at the Press Club of India to mark the anniversary of the execution of Afzal Guru, who was convicted of involvement in an attack on the Indian Parliament in 2001. The police say that Syed Abdul Rehman Geelani led a group of about 50 people in chanting ‘anti-India’ slogans at the event and declaring Afzal Guru a martyr. The police arrested the professor on 16 February. A Delhi court denied him bail on 20 February. He has been remanded in judicial custody. The FIR against students Kanhaiya Kumar, Umar Khalid and Anirban Bhattacharya states that the police received a complaint on 9 February about an event on the JNU campus, also to mark the anniversary of the execution of Afzal Guru. The police said that on 10 February, a television news report about the event showed ‘anti-national’ slogans being chanted. Media reports have suggested that the footage had been doctored. The Delhi police arrested Kanhaiya Kumar, who attended the event, on 12 February, and summoned other students who were present. -

Anil Biswas – Filmography Source: Hamraz’S Hindi Film Geet Kosh (Digitization: Ketan Dholakia, Vinayak Gore, and Balaji Murthy)

Anil Biswas – Filmography Source: Hamraz’s Hindi Film Geet Kosh (Digitization: Ketan Dholakia, Vinayak Gore, and Balaji Murthy) Contents Anil Biswas – Filmography ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1) Dharam Ki Devi ..................................................................................................................... 3 2) Fida-e-Vatan (alias Tasveer-e-vafa) ...................................................................................... 3 3) Piya Ki Jogan (alias Purchased Bride) ................................................................................... 3 4) Pratima (alias Prem Murti) ..................................................................................................... 4 5) Prem Bandhan (alias Victims of Love) .................................................................................. 4 6) Sangdil Samaj ......................................................................................................................... 4 7) Sher Ka Panja ......................................................................................................................... 5 8) Shokh Dilruba ......................................................................................................................... 5 9) Bulldog ................................................................................................................................... 5 10) Dukhiari (alias A Tale of Selfless Love) -

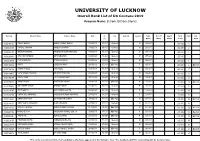

UNIVERSITY of LUCKNOW Overall Rank List of UG Courses-2019 Program Name: B.Com./B.Com.(Hons)

UNIVERSITY OF LUCKNOW Overall Rank List of UG Courses-2019 Program Name: B.Com./B.Com.(Hons) Roll No. Student Name Father's Name DoB Hs. Cat. Sub Cat. Gender Total NCC 'B' Sports Final Rank Cat. (%) Marks Marks Marks Index Rank 1921188424 SURAJ BAGLA MANOJ KUMAR BAGLA 12/04/2002 95.000 General M 289.000 289.000 1 1921238087 VATSAL SHARMA RAKESH SHARMA 03/09/2001 96.500 General M 282.000 282.000 2 1921228151 GAURAV BANSAL RAJENDRA KUMAR BANSAL 19/04/2001 95.000 General M 278.000 278.000 3 1921268380 SHAYAN RAHMANI SOFIYAN KHAN 30/07/2001 76.000 General M 275.000 275.000 4 1921218379 PARAS MISHRA PREM SHANKAR 20/07/2002 95.000 General M 265.000 265.000 5 1921188204 SWATI LOKESH KUMAR 28/07/2002 95.000 OBC-NCL F 265.000 265.000 6 BC0001 1921128124 TANISHA GOEL AJAY GOEL 12/10/2001 90.200 General F 261.000 261.000 7 1921198405 VIJAY SINGH TAMANG MR MANY TAMANG 25/07/2001 93.000 General M 260.000 260.000 8 1921188087 ABHAY DIXIT LALIT KUMAR DIXIT 07/01/2003 90.667 General M 257.000 257.000 9 1921278172 AMAN YADAV SURENDRA YADAV 08/04/2001 88.500 OBC-NCL M 253.000 253.000 10 BC0002 1921178453 ANUSHREE SINGH KESHAR SINGH 11/04/2002 95.000 General F 252.000 252.000 11 1921128147 ADITI GUPTA AJAY KUMAR GUPTA 14/04/2001 96.333 General F 250.000 250.000 12 1921288358 CHANCHAL AGARWAL VIRENDRA KUMAR AGARWAL 27/03/2001 96.200 General F 250.000 250.000 13 1921208492 DHRUV KRISHNA OM PRAKASH VERMA 09/07/2001 90.833 OBC-NCL M 248.000 248.000 14 BC0003 1921138033 ABHYUDAYA CHADDHA ALOK CHADDHA 27/08/2001 95.000 General M 247.000 247.000 15 1921138172 -

Carvaan Mini 2,0 Songlist

SONGS LIST 01. Chura Liya Hai Tumne Jo Dil Ko 11. Badan Pe Sitare Lapete Huye 21. Mere Khwabon Mein 31. O Saathi Re 41. Aaj Mausam Bada Beimaan Hai 51. Hum Dono Do Premi 61. Kuchh To Log Kahenge 71. Taarif Karoon Kya Uski 81. Mere Dil Mein Aaj Kya Hai 91. Tune O Rangeele 101. Aaj Rapat Jaayen To 111. Jeena Yahan Marna Yahan Film: Yaadon Ki Baaraat Film: Prince Film: Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge Film: Muqaddar Ka Sikandar Film: Loafer Film: Ajanabee Film: Amar Prem Film: Kashmir Ki Kali Film: Daag Film: Kudrat Film: Namak Halaal Film: Mera Naam Joker Artistes: Mohammed Rafi, Asha Bhosle Artiste: Mohammed Rafi Artiste: Lata Mangeshkar Artiste: Kishore Kumar Artiste: Mohammed Rafi Artistes: Kishore Kumar, Lata Mangeshkar Artiste: Kishore Kumar Artiste: Mohammed Rafi Artiste: Kishore Kumar Artiste: Lata Mangeshkar Artistes: Kishore Kumar, Asha Bhosle Artiste: Mukesh Lyricist: Majrooh Sultanpuri Lyricist: Hasrat Jaipuri Lyricist: Anand Bakshi Lyricist: Anjaan Lyricist: Anand Bakshi Lyricist: Anand Bakshi Lyricist: Anand Bakshi Lyricist: S.H.Bihari Lyricist: Sahir Ludhianvi Lyricist: Majrooh Sultanpuri Lyricist: Anjaan Lyricist: Shaili Shailendra Music Director: R.D. Burman Music Directors: Shankar - Jaikishan Music Directors: Jatin-Lalit Music Directors: Kalyanji - Anandji Music Directors: Laxmikant - Pyarelal Music Director: R.D. Burman Music Director: R.D. Burman Music Director: O.P. Nayyar Music Directors: Laxmikant - Pyarelal Music Director: R.D. Burman Music Director: Bappi Lahiri Music Directors: Shankar - Jaikishan 02. O Mere Dil Ke Chain 12. Ek Ajnabee Haseena Se 22. Pyar Diwana Hota Hai 32. Chaudhvin Ka Chand Ho 42. Gaata Rahe Mera Dil 52. Phoolon Ke Rang Se 62.