Voice, Not Choice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voice, Not Choice

Book Review Voice, Not Choice Politics, Markets, and America's Schools. By John E. Chubb* and Terry M. Moe.** Washington: The Brookings Institution, 1990. Pp.xvii, 311. $28.95 (cloth), $10.95 (paper). James S. Liebmant You can actively flee, then, and you can actively stay put.' In John Chubb and Terry Moe's book,' choice is hot; voice is not.3 As influential as their book has become in current policy debates,4 however, its * Senior Fellow, The Brookings Institution. ** Professor of Political Science, Stanford University. f Professor of Law, Columbia University School of Law. Bob Crain, Sam Gross, Susan Lusi, James Meier, Richard Murnane, Harriet Rabb, Chuck Sabel, Janet Sabel, Barbara Bennett Woodhouse, and participants in the Columbia Faculty Workshop provided helpful comments on earlier drafts. This Review is part of a larger work being published by Oxford University Press, tentatively entitled POLITICAL DESEGREGATION AND EDUCATIONAL REFORM (forthcoming 1992). 1. ERIK H. ERIKSON, INSIGHT AND RESPONSIBILITY 86 (1964). 2. JOHN E. CHUBB & TERRY M. MOE, PoLmCs, MARKETS, AND AMERICA'S SCHOOLS (1990) [hereinafter by page only]. 3. By "choice" I mean reliance on consumers' purchase or rejection of services to determine the services' future traits and distribution. By "voice" I mean reliance on constituents' expressions about the value of particular services to make the same determination. "Choice" typically uses market mechanisms to coordinate individual actions. See infra notes 163-72 and accompanying text. "Voice" often uses democratic procedures to shape collective action. See infra notes 255-68 and accompanying text. 4. The extensive press coverage given to the book includes Susan Chira, The Rules of the Marketplace Are Applied to the Classroom, N.Y. -

"1683-1920"; the Fourteen Points and What Became of Them--Foreign

^^0^ ^oV^ '•^0^ 4^°^ '/ COPYRIGHT BY 1920 g)CU566029 ^ PUBLISHED BY CONCORD PUBLISHING COMPANY INCORPORATED NEW YORK, U. S. A. ^^^^^eM/uj^ v//^j^#<>tdio ^t^^u^^ " 1 683- 1 920 The Fourteen Points and What Became of Them— Foreign Propaganda in the Public Schools — Rewriting the History of the United States—The Espionage Act and How it Worked— "Illegal and Indefensible Blockade" of the Central Powers— 1.000.000 Victims of Starvation—Our Debt to France and to Germany—The War Uote in Congress — Truth About the Belgian Atrocities— Our Treaty with Germany and How Observed— The Alien Property Custodianship- Secret Will of Cecil Rhodes— Racial Strains in American Life — Germantown Settle- ment of 1683 And a Thousand Other Topics by Frederick Frankun Schrader Former Secretary Republican Congressional Committee and Author "Republican Campaign Text Book. 1898.** (i PREFACE WITH the ending of the war many books will be released dealing with various questions and phases of the great struggle, some of them perhaps impartial, but the majority written to make propaganda for foreign nations with a view to rendering us dissatisfied with our country and imposing still "•- -v,^^ ,it^^,n fiiA iVnorance. indifference and credulity of the Amer- NOTE The short quotations from Mere Literature, by President raised Wi -fvr'i oodrow Wilson, printed on pages II, 95, 166, 224, and 226 of ,, this volume are used by special arrangement with Messrs. Houghton g and Mifflin Company, A blanket indictment has been found against a whole race. That race comprises upward of 26 per cent, of the American people and has been a stalwart factor in American life since the middle of the seventeenth century. -

American Tax Resisters

American Tax Resisters AMERICAN TAX RESISTERS Romain D. Huret Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, En gland 2014 Copyright © 2014 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Publication of this book has been supported through the generous provisions of the Maurice and Lula Bradley Smith Memorial Fund. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Huret, Romain. American tax resisters / Romain D. Huret. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 674- 28137- 0 (alk. paper) 1. Taxation— United States— History. 2. Income tax— United States— History. 3. Tax evasion— United States— History. 4. Finance, Public— United States— History. 5. Equality— United States— History. I. Title. HJ2362.H87 2014 336.200973—dc23 2013032961 To Ariane, Emilien, Melvil, and Raphaël Contents Prologue 1 1. Unconstitutional War Taxes 13 2. Down with Internal Taxes 45 3. The Odious Income Tax 78 4. Not for Mothers, Not for Soldiers 110 5. The Bread- and- Circus Democracy 141 6. From the Kitchen to the Capital? 173 7. The Tyranny of the “Infernal Revenue Ser vice” 208 8. Tea Parties All Over Again? 241 Epilogue 274 List of Abbreviations 283 Notes 285 Ac know ledg ments 356 Index 359 American Tax Resisters Prologue In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes. —Benjamin Franklin (1789) Benjamin Franklin’s witty remark is familiar today to most American citizens. Each year, on April 15, many share his fatalistic sentiment when they rush to fi ll in their tax return and send it to the Internal Revenue Ser vice. -

View on the Quest for Racial Justice in the United States and Across the African

Pride and Protest in Letters and Song: Jazz Artists and Writers during the Civil Rights Movement, 1955-1965 A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Jack R. Marchbanks May 2018 © 2018 Jack R. Marchbanks. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Pride and Protest in Letters and Song: Jazz Artists and Writers during the Civil Rights Movement, 1955-1965 by JACK R. MARCHBANKS has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Kevin Mattson, PhD Professor of Contemporary History Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT MARCHBANKS JACK R., Ph.D., May 2018, History Pride and Protest in Letters and Song: Jazz Artists and Writers during the Civil Rights Movement, 1955-1965 Director of Dissertation: Kevin Mattson Pride and Protest in Letters and Song is a traditional historical narrative which examines racial justice advocacy, as expressed in artistic works by several preeminent jazz musicians and the writers who allied with them during the pivotal 1955 to 1965 span of the American Civil Rights Movement. The work interrogates milestone confrontations during the civil rights movement, such as the Little Rock Nine Crisis, the African Anticolonial Movement, and the pivotal 1963 direct action campaigns waged by Martin Luther King, Jr. and the SCLC, the NAACP and SNCC. The aim of this method of historical inquiry is to determine why and how these events motivated the profiled musicians and writers to use their gifts to express opinions on the racial tumult of the era. -

Meyer and Pierce and the Child As Property

William & Mary Law Review Volume 33 (1991-1992) Issue 4 Article 2 May 1992 "Who Owns the Child?": Meyer and Pierce and the Child as Property Barbara Bennett Woodhouse Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Family Law Commons Repository Citation Barbara Bennett Woodhouse, "Who Owns the Child?": Meyer and Pierce and the Child as Property, 33 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 995 (1992), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol33/iss4/2 Copyright c 1992 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr William and Mary Law Review VOLUME 33 SUMMER 1992 NUMBER 4 "WHO OWNS THE CHILD?": MEYER AND PIERCE AND THE CHILD AS PROPERTY BARBARA BENNETT WOODHOUSE* I. THE NATURE OF THE PROJECT ...................................... 996 II. LANGUAGE LAWS, COMMON SCHOOLING, AND THE POLITICS OF PLURALISM .................................................. 1002 A. Language Laws and Common Schooling in HistoricalContext .................................................... 1003 B. Americanization as a National Progressive Reform Movement ..................................................... 1009 C. A Test Case: Metamporphosis from Religious Liberty to ParentalRights ...................................... 1012 * Assistant Professor of Law, University of Pennsylvania Law School. B.S., University of the State of New York, 1980; J.D., Columbia Law School, 1983. I owe a debt to the many librarians and archivists who extended courtesies and assistance to me, expecially archivist Marsha Trimble of the University of Virginia Law Library Special Collections (McReynolds Papers), Philip Oxley of the Columbia Law Library (Guthrie materials), the Philadelphia Public Library, the New York Public Library, and the Manu- script Division of the Library of Congress (Sutherland Papers). -

View PDF Editionarrow Forward

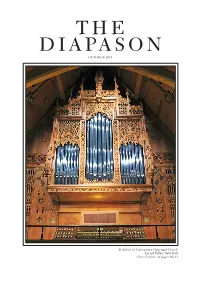

THE DIAPASON OCTOBER 2014 St. John’s of Lattingtown Episcopal Church Locust Valley, New York Cover feature on pages 30–31 “A true revelation…. He is an eloquent musician. His rhythmic sense is clear-cut American. His feet elegantly tap dance on the pedals. Everything he plays is sharply and smartly delineated. His tempos were on the satisfyingly quick side, yet so naturally that nothing felt rushed or unduly showy. ….Most listened to emotionally and musically challenging, unfamiliar pieces with riveted attention…an unnervingly honest and direct performance, astonishing for so young a performer. The Houli fans can give themselves high fives. They’ve helped launch a major career.” CHRISTOPHER Mark Swed, Music Critic, HOULIHAN Los Angeles Times [email protected] (860)-560-7800 www.concertartists.com THE DIAPASON Editor’s Notebook Scranton Gillette Communications One Hundred Fifth Year: No. 10, In this issue Whole No. 1259 Composer, performer, and teacher William Albright would OCTOBER 2014 have celebrated his seventieth birthday this month, and Established in 1909 Douglas Reed has paid tribute in a pair of interviews with two Joyce Robinson ISSN 0012-2378 persons very close to Albright; they provide a portrait with both 847/391-1044; [email protected] personal and professional views. www.TheDiapason.com An International Monthly Devoted to the Organ, Cicely Winter reports on the organ and early music festival the Harpsichord, Carillon, and Church Music that took place in Oaxaca, Mexico, in February; the group of All this is in addition to our regular columns of news, reviews, which she is president has led the restoration efforts for an international calendar, and organ recitals. -

BARBARA BENNETT WOODHOUSE Emory University School of Law 1301 Clifton Rd

BARBARA BENNETT WOODHOUSE Emory University School of Law 1301 Clifton Rd. Rm. 512 Atlanta, Georgia 30322 [email protected] Current as of 2/2019 ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Emory University Emory University School of Law L.Q.C. Lamar Professor of Law (2009 to present) Center for Comparative and International Law, Faculty (2010 to present) Center for the Study of Law and Religion, Faculty (2010 to present) Vulnerability and the Human Condition Initiative, Faculty (2009 to present) Child Rights Project, Founding Director (2011 to present) Barton Child Law and Policy Center, Co-Director and Acting Director (2009 to 2011) University of Florida Fredric G. Levin College of Law David H. Levin Chair in Family Law (2001 to 2009) David H. Levin Chair Emeritus (2009 to present) Center on Children and Families, Founding Director (2001to 2009) University of Pennsylvania Professor of Law (1988-2001) Center for Children’s Policy Practice and Research, Founding Co-Director (1998 to 2001) European University Institute Fernand Braudel Senior Fellow Firenze, Italia Fall 2007 to Spring 2008 COURSES AND SEMINARS* Adoption Child, Parent and State Child Welfare Law Children’s Rights Children’s Rights Appellate Practicum 1 Comparative and International Family Law Conflict of Laws Constitutional Law Education for the Professions Family Law Perspectives on the Family Child Law Policy and Advocacy Clinic Equality and the 14th Amendment Seminar* Public Interest Practice Seminar* The Supreme Court and the Family* Selected Topics in Family Law* Critical Perspectives on Intimate Partner Violence* EDUCATION Columbia University Law School Juris Doctor 1983 Columbia Law Review: Notes and Comments Editor Comment: Powell v.