A Study of Popular Hong Kong Cinema from 2001 to 2004 As Resource for a Contextual Approach to Expressions of Christian Faith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

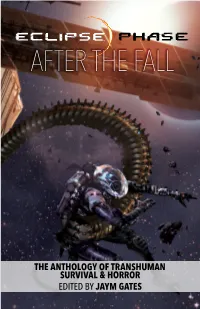

Eclipse Phase: After the Fall

AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 Advance THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN Reading SURVIVAL & HORROR Copy Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. Some content licensed under a Creative Commons License (BY-NC-SA); Some Rights Reserved. © 2016 AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN SURVIVAL & HORROR Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. -

Bullet in the Head

JOHN WOO’S Bullet in the Head Tony Williams Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Tony Williams 2009 ISBN 978-962-209-968-5 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Condor Production Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents Series Preface ix Acknowledgements xiii 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head 1 2 Bullet in the Head 23 3 Aftermath 99 Appendix 109 Notes 113 Credits 127 Filmography 129 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head Like many Hong Kong films of the 1980s and 90s, John Woo’s Bullet in the Head contains grim forebodings then held by the former colony concerning its return to Mainland China in 1997. Despite the break from Maoism following the fall of the Gang of Four and Deng Xiaoping’s movement towards capitalist modernization, the brutal events of Tiananmen Square caused great concern for a territory facing many changes in the near future. Even before these disturbing events Hong Kong’s imminent return to a motherland with a different dialect and social customs evoked insecurity on the part of a population still remembering the violent events of the Cultural Revolution as well as the Maoist- inspired riots that affected the colony in 1967. -

QUARTERLY REPORT 2005/2006 for the Nine Months Ended 31 December, 2005

PANORAMA INTERNATIONAL HOLDINGS LIMITED 鐳射國際控股有限公司* (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) (Stock Code: 8173) THIRD QUARTERLY REPORT 2005/2006 For the nine months ended 31 December, 2005 * For identification purposes only CHARACTERISTICS OF THE GROWTH ENTERPRISE MARKET (“GEM”) OF THE STOCK EXCHANGE OF HONG KONG LIMITED (THE “STOCK EXCHANGE”) GEM has been established as a market designed to accommodate companies to which a high investment risk may be attached. In particular, companies may list on GEM with neither a track record of profitability nor any obligation to forecast future profitability. Furthermore, there may be risks arising out of the emerging nature of companies listed on GEM and the business sectors or countries in which the companies operate. Prospective investors should be aware of the potential risks of investing in such companies and should make the decision to invest only after due and careful consideration. The greater risk profile and other characteristics of GEM mean that it is a market more suited to professional and other sophisticated investors. Given the emerging nature of companies listed on GEM, there is a risk that securities traded on GEM may be more susceptible to high market volatility than securities traded on the Main Board of the Stock Exchange and no assurance is given that there will be a liquid market in the securities traded on GEM. The principal means of information dissemination on GEM is publication on the Internet website operated by the Stock Exchange. Listed companies are not generally required to issue paid announcements in gazetted newspapers. Accordingly, prospective investors should note that they need to have access to the GEM website in order to obtain up-to-date information on GEM-listed issuers. -

Feff Press Kit

PRESS RELEASES, FILM STILLS & FESTIVAL PICS AND VIDEOS TO DOWNLOAD FROM WWW.FAREASTFILM.COM PRESS AREA Press Office/Far East Film Festival 19 Gianmatteo Pellizzari & Ippolita Nigris Cosattini +39/0432/299545 - +39/347/0950890 [email protected] - [email protected] Video Press Office Matteo Buriani +39/345/1821517 – [email protected] 21/29 April 2017 – Udine – Teatro Nuovo and Visionario FAR EAST FILM FESTIVAL 19: THE POWER OF ASIA! The irresistible road movie Survival Family opens the #FEFF19 on Friday the 21 st of April: a packed programme which testifies to the incredible vitality (both productive and creative) of Asian cinema. 83 titles selected from almost a thousand seen, and 4 world premiers, including Herman Yau's high-octane thriller Shock Wave , which will close the nineteenth edition. Press release of the 13 th of April 2017 For immediate release UDINE - Who turned out the lights? Nobody did, and the fuses haven't blown. And no, it's not even a power cut. Electricity has just suddenly ceased to exist, so the Suzuki family must now very quickly learn the art of survival: and facing a global blackout is not exactly a walk in the park! It's with the world screeching to a halt of the irresistible Japanese road movie Survival Family that the highly anticipated Far East Film Festival 19 opens: not just because Yaguchi Shinobu' s wonderful comedy is the festival's starting pistol on Friday the 21 st of April, but also for a question of symmetry: just like the blackout in Survival Family , the FEFF is an interruption . -

Electric Shadows PK

ELECTRIC SHADOWS A Film by Xiao Jiang 95 Minutes, Color, 2004 35mm, 1:1.85, Dolby SR In Mandarin w/English Subtitles FIRST RUN FEATURES The Film Center Building 630 Ninth Ave. #1213 New York, NY 10036 (212) 243-0600 Fax (212) 989-7649 Website: www.firstrunfeatures.com Email: [email protected] ELECTRIC SHADOWS A film by Xiao Jiang Short Synopsis: From one of China's newest voices in cinema and new wave of young female directors comes this charming and heartwarming tale of a small town cinema and the lifelong influence it had on a young boy and young girl who grew up with the big screen in that small town...and years later meet by chance under unusual circumstances in Beijing. Long Synopsis: Beijing, present. Mao Dabing (‘Great Soldier’ Mao) has a job delivering bottled water but lives for his nights at the movies. One sunny evening after work he’s racing to the movie theatre on his bike when he crashes into a pile of bricks in an alleyway. As he’s picking himself up, a young woman who saw the incident picks up a brick and hits him on the head... He awakens in the hospital with his head bandaged. The police tell him that he’s lost his job, and that his ex-boss expects him to pay for the wrecked bicycle. By chance he sees the young woman who hit him and angrily remonstrates with her. But she seems not to hear him, and hands him her apartment keys and a note asking him to feed her fish. -

Download This PDF File

Humanity 2012 Papers. ~~~~~~ “‘We are all the same, we are all unique’: The paradox of using individual celebrity as metaphor for national (transnational) identity.” Joyleen Christensen University of Newcastle Introduction: This paper will examine the apparently contradictory public persona of a major star in the Hong Kong entertainment industry - an individual who essentially redefined the parameters of an industry, which is, itself, a paradox. In the last decades of the 20th Century, the Hong Kong entertainment industry's attempts to translate American popular culture for a local audience led to an exciting fusion of cultures as the system that was once mocked by English- language media commentators for being equally derivative and ‘alien’, through translation and transmutation, acquired a unique and distinctively local flavour. My use of the now somewhat out-dated notion of East versus West sensibilities will be deliberate as it reflects the tone of contemporary academic and popular scholarly analysis, which perfectly seemed to capture the essence of public sentiment about the territory in the pre-Handover period. It was an explicit dichotomy, with commentators frequently exploiting the notion of a culture at war with its own conception of a national identity. However, the dwindling Western interest in Hong Kong’s fate after 1997 and the social, economic and political opportunities afforded by the reunification with Mainland China meant that the new millennia saw Hong Kong's so- called ‘Culture of Disappearance’ suddenly reconnecting with its true, original self. Humanity 2012 11 Alongside this shift I will track the career trajectory of Andy Lau – one of the industry's leading stars1 who successfully mimicked the territory's movement in focus from Western to local and then regional. -

Warriors As the Feminised Other

Warriors as the Feminised Other The study of male heroes in Chinese action cinema from 2000 to 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chinese Studies at the University of Canterbury by Yunxiang Chen University of Canterbury 2011 i Abstract ―Flowery boys‖ (花样少年) – when this phrase is applied to attractive young men it is now often considered as a compliment. This research sets out to study the feminisation phenomena in the representation of warriors in Chinese language films from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mainland China made in the first decade of the new millennium (2000-2009), as these three regions are now often packaged together as a pan-unity of the Chinese cultural realm. The foci of this study are on the investigations of the warriors as the feminised Other from two aspects: their bodies as spectacles and the manifestation of feminine characteristics in the male warriors. This study aims to detect what lies underneath the beautiful masquerade of the warriors as the Other through comprehensive analyses of the representations of feminised warriors and comparison with their female counterparts. It aims to test the hypothesis that gender identities are inventory categories transformed by and with changing historical context. Simultaneously, it is a project to study how Chinese traditional values and postmodern metrosexual culture interacted to formulate Chinese contemporary masculinity. It is also a project to search for a cultural nationalism presented in these films with the examination of gender politics hidden in these feminisation phenomena. With Laura Mulvey‘s theory of the gaze as a starting point, this research reconsiders the power relationship between the viewing subject and the spectacle to study the possibility of multiple gaze as well as the power of spectacle. -

How Superman Developed Into a Jesus Figure

HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE CRISIS ON INFINITE TEXTS: HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE By ROBERT REVINGTON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Robert Revington, September 2018 MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario, Religious Studies TITLE: Crisis on Infinite Texts: How Superman Developed into a Jesus Figure AUTHOR: Robert Revington, B.A., M.A (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies LAY ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. It argues that this connection was not integral to the character as he was originally created, but was imposed by later writers over time and mainly for cinematic adaptations. This thesis also tracks the history of how Christians and churches viewed Superman, as the film studios began to exploit marketing opportunities by comparing Superman and Jesus. This thesis uses the methodological framework of intertextuality to ground its treatment of the sources, but does not follow all of the assumptions of intertextual theorists. iii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. Superman was created in 1938, but the character developed significantly from his earliest incarnations. -

FLORENCE AS CHRIST-FIGURE in DOMBEY and SON Sarah Flenniken John Carroll University, [email protected]

John Carroll University Carroll Collected Masters Essays Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects Spring 2017 TOUCHED BY LOVE: FLORENCE AS CHRIST-FIGURE IN DOMBEY AND SON Sarah Flenniken John Carroll University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/mastersessays Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Flenniken, Sarah, "TOUCHED BY LOVE: FLORENCE AS CHRIST-FIGURE IN DOMBEY AND SON" (2017). Masters Essays. 61. http://collected.jcu.edu/mastersessays/61 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Essays by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOUCHED BY LOVE: FLORENCE AS CHRIST-FIGURE IN DOMBEY AND SON An Essay Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies College of Arts & Sciences of John Carroll University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Sarah Flenniken 2017 The essay of Sarah Flenniken is hereby accepted: ______________________________________________ __________________ Advisor- Dr. John McBratney Date I certify that this is the original document ______________________________________________ __________________ Author- Sarah E. Flenniken Date A recent movement in Victorian literary criticism involves a fascination with tactile imagery. Heather Tilley wrote an introduction to an essay collection that purports to “deepen our understanding of the interconnections Victorians made between mind, body, and self, and the ways in which each came into being through tactile modes” (5). According to Tilley, “who touched whom, and how, counted in nineteenth-century society” and literature; in the collection she introduces, “contributors variously consider the ways in which an increasingly delineated touch sense enabled the articulation and differing experience of individual subjectivity” across a wide range of novels and even disciplines (1, 7). -

Written & Directed by and Starring Stephen Chow

CJ7 Written & Directed by and Starring Stephen Chow East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor IHOP Public Relations Block Korenbrot PR Sony Pictures Classics Jeff Hill Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Jessica Uzzan Judy Chang Leila Guenancia 853 7th Ave, 3C 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 212-265-4373 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel 212-247-2948 fax 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax 1 Short Synopsis: From Stephen Chow, the director and star of Kung Fu Hustle, comes CJ7, a new comedy featuring Chow’s trademark slapstick antics. Ti (Stephen Chow) is a poor father who works all day, everyday at a construction site to make sure his son Dicky Chow (Xu Jian) can attend an elite private school. Despite his father’s good intentions to give his son the opportunities he never had, Dicky, with his dirty and tattered clothes and none of the “cool” toys stands out from his schoolmates like a sore thumb. Ti can’t afford to buy Dicky any expensive toys and goes to the best place he knows to get new stuff for Dicky – the junk yard! While out “shopping” for a new toy for his son, Ti finds a mysterious orb and brings it home for Dicky to play with. To his surprise and disbelief, the orb reveals itself to Dicky as a bizarre “pet” with extraordinary powers. Armed with his “CJ7” Dicky seizes this chance to overcome his poor background and shabby clothes and impress his fellow schoolmates for the first time in his life. -

Филмð¾ð³ñ€Ð°Ñ„иÑ)

Ng Man-tat Филм ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (ФилмографиÑ) The Wandering Earth https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-wandering-earth-57966215/actors The Royal Scoundrel https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-royal-scoundrel-4902561/actors My Heart Is That Eternal Rose https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/my-heart-is-that-eternal-rose-3331191/actors Gameboy Kids https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/gameboy-kids-2119212/actors A Better Tomorrow 2 https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-better-tomorrow-2-787091/actors Sixty Million Dollar Man https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/sixty-million-dollar-man-3485767/actors A Chinese Odyssey https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-chinese-odyssey-868483/actors All for the Winner https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/all-for-the-winner-2837581/actors Tricky Brains https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/tricky-brains-775390/actors A Chinese Odyssey Part Two: https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-chinese-odyssey-part-two%3A-cinderella- Cinderella 3278995/actors Lee Rock II https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/lee-rock-ii-10881515/actors Shaolin Soccer https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/shaolin-soccer-536299/actors Fight Back to School https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/fight-back-to-school-3071625/actors King of Beggars https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/king-of-beggars-6412210/actors The Mad Monk https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-mad-monk-3275152/actors Holy Weapon https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/holy-weapon-1092407/actors -

Some Ideas on the Direction of Chinese Theological Development

July-August 1969 Vol. XX, No.6 Library IlJ ~ 1 fj r,,,t<lw dYl al J 2 0t ll ~ ,lr ~ c tJ Ne w Yo r k . N Y 10 (,;,/ 1"If' p ii ollc (Arc" ;'>12) (,0 2 71 0 0 Subscription: $3 a year; 1-15 copies, 35¢ Edrtonat Otfice liol liO b / R. 47 5 Rl vcrSlclc Dr rve. New Yu rk N Y I OI)?1 each; 16-50 copies, 25¢ each; l ctepno ne (A red :' I ? ) H70 ? 1 / 5 Circulation OHice (,3 7 We" 1251 11 st .. Ncv. Yor k. N Y 100 21 more than 50 copies, 15¢ each re leph o ne ( Area :'12) 8,0 2') 10 SOME IDEAS ON THE DIRECTION OF CHINESE THEOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT (An analysis of the features contributing to the lack of Chinese theologi cal productivity and a presentation of some ideas on the biblical direction of Chinese theological development; together with a preliminary bibliogra phy. (Since the beginning of the Cultural Revolution in August 1966, there has been no word of any theological activity in mainland China. The last re maining theological center, Nanking Theological Seminary, has been closed.) Jonathan Tien-En Chao'" I. INTRODUCTION In recent years t he r e has been a gr owi ng interest within the Chinese Christian community in the a reas of "Chi nese native-colored theology," the relationship between Christianity and Chinese cul t ure, the appropriateness of Chinese foreign missions projects, and the "indigenous church." These topics usually arouse peculiar interest among most Chinese Christians. Their central appeal is to the concept of the dis tinctly indigenous "Chinese" approach.