The American Alpine Journal. I992

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Umbrella Falls Trail #667 Northwest Forest Pass Required Recreation Opportunity Guide May 15 - Oct 1

Umbrella Falls Trail #667 Northwest Forest Pass Required Recreation Opportunity Guide May 15 - Oct 1 Distance ........................................ 3.1 miles (one way) Elevation ....................................... 4550-5750 feet Snow Free .................................... July to October More Difficult Trail Highlights: This trail is on the southeast side of Mount Hood. The trail passes Umbrella Falls on the way to the Mount Hood Meadows Ski Area. The trail provides easy access to Timberline Trail #600. Trail Description: This trail begins at its junction with Timberline Trail #600, heads southeast and ends at its junction with Sahalie Falls Trail #667C. From Timberline Trail #600 (5,800’), the trail heads southeast through a meadow and crosses two small creeks. After 0.4 miles, the trail switches back several times before heading north another 0.3 mile to Mitchell Creek (5,540’). Cross Mitchell Creek on the wooden bridge and continue downhill (southeast) 0.5 mile to Mount Hood Meadows Road (5,200’). (This is a good place to start the hike). Cross Mount Hood Meadows Road and follow the trail north 0.25 mile to Umbrella Falls (5,250’). Continue past the falls 0.25 mile to the first junction with Sahalie Falls Trail #667C. Continue from the junction, crossing several ski runs, 1.3 miles to the second junction with Sahalie Falls Trail #667C and the end of this trail. Hikers can return on this trail or take Sahalie Falls Trail #667C 2.1 miles back to the first junction with this trail. Regulations & Leave No Trace Information: There are no bikes allowed between Timberline Trail #600 and Forest Road 3555. -

Lewis and Clark Mount Hood Final Wilderness Map 2009

!( !( !( !( !( !( !( R. 4 E. R. 5 E. R. 6 E. R. 7 E. R. 8 E. R. 9 E. R. 10 E. R. 11 E. R. 12 E. R. 13 E. (!141 !( !( !( n (!14 o ER 142 t RIV (! !( 14 (! 30 !( g IA ¤£ HOOD a MB 84 e LU ¨¦§ RIVER n Ar CO !( i WYETH VIENTO c !( i en !( h ROCKFORD MOSIER !( c 14 S !( !( (! ROWENA s l a ¤£30 a CASCADE 00 ! n !( 20 o LOCKS OAK GROVE i !( !( t !35 a R. ( 30 W N Hood !(VAN ¤£ T. HORN 2 !( 197 ge ¤£ N. or CRATES G BONNEVILLE 84 POINT !( ¨¦§ ODELL !( !( Gorge Face !( 84 500 er ¨¦§ (! 140 v MARK O. HATFIELD !( !( (! i !( R WILDERNESS !( !( a HOOD RIVER WASCO i !( WINANS THE DALLES !( b COUNTY COUNTY um !( l DEE !( !( !( o E !( ER . C IV F Wahtum R k. !( Ea Lake g . le r Cr. MULTNOMAH A C BI FALLS!( l . M a R LU p d O O E C o o . F T. 14 H 17 T. ! . ( k Ý BRIDAL k . !( H 1 VEIL F 1 . o N. ! M o !( N. !( !( 84 d MOUNT § R FAIRVIEW ¨¦ 15 HOOD 30 !( Ý . !( !( !( Byp 0 TROUTDALE CORBETT LATOURELL FALLS 0 ¤£ 0 2 Ý13 !( !( Ý20 !( HOOD RIVER WASCO PARKDALE !( !( !( !( !( COUNTY COUNTY TWELVEMILE SPRINGDALE Bu Ý18 Larch Mountain ll CORNER R 16 !( !( Ý10 u Ý ENDERSBY n !( !( R Lost !( Bull Run . Middle Fork !( Lake !( !( !( GRESHAM Reservoir #1 Hood River ! !( T. T. !( Elk Cove/ 1 Mazama 1 S. Laurance 35 S. !( Ý12 (! ORIENT Ý MULTNOMAH COUNTY Lake DUFUR !( !( !( CLACKAMAS COUNTY ! COTRELL Bull Run ! !( Lake Shellrock ile Cr. -

Los Cien Montes Más Prominentes Del Planeta D

LOS CIEN MONTES MÁS PROMINENTES DEL PLANETA D. Metzler, E. Jurgalski, J. de Ferranti, A. Maizlish Nº Nombre Alt. Prom. Situación Lat. Long. Collado de referencia Alt. Lat. Long. 1 MOUNT EVEREST 8848 8848 Nepal/Tibet (China) 27°59'18" 86°55'27" 0 2 ACONCAGUA 6962 6962 Argentina -32°39'12" -70°00'39" 0 3 DENALI / MOUNT McKINLEY 6194 6144 Alaska (USA) 63°04'12" -151°00'15" SSW of Rivas (Nicaragua) 50 11°23'03" -85°51'11" 4 KILIMANJARO (KIBO) 5895 5885 Tanzania -3°04'33" 37°21'06" near Suez Canal 10 30°33'21" 32°07'04" 5 COLON/BOLIVAR * 5775 5584 Colombia 10°50'21" -73°41'09" local 191 10°43'51" -72°57'37" 6 MOUNT LOGAN 5959 5250 Yukon (Canada) 60°34'00" -140°24’14“ Mentasta Pass 709 62°55'19" -143°40’08“ 7 PICO DE ORIZABA / CITLALTÉPETL 5636 4922 Mexico 19°01'48" -97°16'15" Champagne Pass 714 60°47'26" -136°25'15" 8 VINSON MASSIF 4892 4892 Antarctica -78°31’32“ -85°37’02“ 0 New Guinea (Indonesia, Irian 9 PUNCAK JAYA / CARSTENSZ PYRAMID 4884 4884 -4°03'48" 137°11'09" 0 Jaya) 10 EL'BRUS 5642 4741 Russia 43°21'12" 42°26'21" West Pakistan 901 26°33'39" 63°39'17" 11 MONT BLANC 4808 4695 France 45°49'57" 06°51'52" near Ozero Kubenskoye 113 60°42'12" c.37°07'46" 12 DAMAVAND 5610 4667 Iran 35°57'18" 52°06'36" South of Kaukasus 943 42°01'27" 43°29'54" 13 KLYUCHEVSKAYA 4750 4649 Kamchatka (Russia) 56°03'15" 160°38'27" 101 60°23'27" 163°53'09" 14 NANGA PARBAT 8125 4608 Pakistan 35°14'21" 74°35'27" Zoji La 3517 34°16'39" 75°28'16" 15 MAUNA KEA 4205 4205 Hawaii (USA) 19°49'14" -155°28’05“ 0 16 JENGISH CHOKUSU 7435 4144 Kyrghysztan/China 42°02'15" 80°07'30" -

Geologic Maps of the Eastern Alaska Range, Alaska, (44 Quadrangles, 1:63360 Scale)

Report of Investigations 2015-6 GEOLOGIC MAPS OF THE EASTERN ALASKA RANGE, ALASKA, (44 quadrangles, 1:63,360 scale) descriptions and interpretations of map units by Warren J. Nokleberg, John N. Aleinikoff, Gerard C. Bond, Oscar J. Ferrians, Jr., Paige L. Herzon, Ian M. Lange, Ronny T. Miyaoka, Donald H. Richter, Carl E. Schwab, Steven R. Silva, Thomas E. Smith, and Richard E. Zehner Southeastern Tanana Basin Southern Yukon–Tanana Upland and Terrane Delta River Granite Jarvis Mountain Aurora Peak Creek Terrane Hines Creek Fault Black Rapids Glacier Jarvis Creek Glacier Subterrane - Southern Yukon–Tanana Terrane Windy Terrane Denali Denali Fault Fault East Susitna Canwell Batholith Glacier Maclaren Glacier McCallum Creek- Metamorhic Belt Meteor Peak Slate Creek Thrust Broxson Gulch Fault Thrust Rainbow Mountain Slana River Subterrane, Wrangellia Terrane Phelan Delta Creek River Highway Slana River Subterrane, Wrangellia Terrane Published by STATE OF ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF GEOLOGICAL & GEOPHYSICAL SURVEYS 2015 GEOLOGIC MAPS OF THE EASTERN ALASKA RANGE, ALASKA, (44 quadrangles, 1:63,360 scale) descriptions and interpretations of map units Warren J. Nokleberg, John N. Aleinikoff, Gerard C. Bond, Oscar J. Ferrians, Jr., Paige L. Herzon, Ian M. Lange, Ronny T. Miyaoka, Donald H. Richter, Carl E. Schwab, Steven R. Silva, Thomas E. Smith, and Richard E. Zehner COVER: View toward the north across the eastern Alaska Range and into the southern Yukon–Tanana Upland highlighting geologic, structural, and geomorphic features. View is across the central Mount Hayes Quadrangle and is centered on the Delta River, Richardson Highway, and Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS). Major geologic features, from south to north, are: (1) the Slana River Subterrane, Wrangellia Terrane; (2) the Maclaren Terrane containing the Maclaren Glacier Metamorphic Belt to the south and the East Susitna Batholith to the north; (3) the Windy Terrane; (4) the Aurora Peak Terrane; and (5) the Jarvis Creek Glacier Subterrane of the Yukon–Tanana Terrane. -

Annual Climate Monitoring Report for Denali National Park and Preserve, Wrangell-St-Elias National Park and Preserve and Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve

Annual Climate Monitoring Report for Denali National Park and Preserve, Wrangell-St-Elias National Park and Preserve and Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve Pamela J. Sousanes Denali National Park and Preserve P.O. Box 9 Denali Park, AK 99755 2005 Central Alaska Network NPS Report Series Number: NPS/AKCAKN/NRTR-2006/0xx Project Number: CAKN-xxxxxx Funding Source: Central Alaska Network Denali National Park and Preserve Draft 2005 Annual Climate Monitoring Report – March 2006 Central Alaska Inventory and Monitoring Network File Name: Sousanes_P_2006_ClimateMonitoringCAKN_0315.doc Recommended Citation: Sousanes, Pamela J. 2006. Annual Climate Monitoring Report for Denali National Park and Preserve, Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, and Yukon- Charley Rivers National Preserve. NPS/AKCAKN/NRTR-2006/xx. National Park Service. Denali Park, AK. 75 pg. Acronyms: I&M Inventory and Monitoring CAKN Central Alaska Network DENA Denali National Park and Preserve WRST Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve YUCH Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve NPS National Park Service WRCC Western Regional Climate Center NRCS Natural Resources Conservation Service NWS National Weather Service RAWS Remote Automated Weather Station NCDC National Climatic Data Center AWOS Automated Weather Observation Station SNOTEL Snow Telemetry ii Draft 2005 Annual Climate Monitoring Report – March 2006 Central Alaska Inventory and Monitoring Network Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................. -

Alaska Range

Alaska Range Introduction The heavily glacierized Alaska Range consists of a number of adjacent and discrete mountain ranges that extend in an arc more than 750 km long (figs. 1, 381). From east to west, named ranges include the Nutzotin, Mentas- ta, Amphitheater, Clearwater, Tokosha, Kichatna, Teocalli, Tordrillo, Terra Cotta, and Revelation Mountains. This arcuate mountain massif spans the area from the White River, just east of the Canadian Border, to Merrill Pass on the western side of Cook Inlet southwest of Anchorage. Many of the indi- Figure 381.—Index map of vidual ranges support glaciers. The total glacier area of the Alaska Range is the Alaska Range showing 2 approximately 13,900 km (Post and Meier, 1980, p. 45). Its several thousand the glacierized areas. Index glaciers range in size from tiny unnamed cirque glaciers with areas of less map modified from Field than 1 km2 to very large valley glaciers with lengths up to 76 km (Denton (1975a). Figure 382.—Enlargement of NOAA Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) image mosaic of the Alaska Range in summer 1995. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration image mosaic from Mike Fleming, Alaska Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, Anchorage, Alaska. The numbers 1–5 indicate the seg- ments of the Alaska Range discussed in the text. K406 SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD and Field, 1975a, p. 575) and areas of greater than 500 km2. Alaska Range glaciers extend in elevation from above 6,000 m, near the summit of Mount McKinley, to slightly more than 100 m above sea level at Capps and Triumvi- rate Glaciers in the southwestern part of the range. -

Chapter Four

Chapter Four South Denali Visitor Center Complex: Interpretive Master Plan Site Resources Tangible Natural Site Features 1. Granite outcroppings and erratic Resources are at the core of an boulders (glacial striations) interpretive experience. Tangible resources, those things that can be seen 2. Panoramic views of surrounding or touched, are important for connecting landscape visitors physically to a unique site. • Peaks of the Alaska Range Intangible resources, such as concepts, (include Denali/Mt. McKinley, values, and events, facilitate emotional Mt. Foraker, Mt. Hunter, Mt. and meaningful experiences for visitors. Huntington, Mt. Dickey, Moose’s Effective interpretation occurs when Erratic boulders on Curry Ridge. September, 2007 Tooth, Broken Tooth, Tokosha tangible resources are connected with Mountains) intangible meanings. • Peters Hills • Talkeetna Mountains The visitor center site on Curry Ridge maximizes access to resources that serve • Braided Chulitna River and valley as tangible connections to the natural and • Ruth Glacier cultural history of the region. • Curry Ridge The stunning views from the visitor center site reveal a plethora of tangible Mt. McKinley/Denali features that can be interpreted. This Mt. Foraker Mt. Hunter Moose’s Tooth shot from Google Earth shows some of the major ones. Tokosha Ruth Glacier Mountains Chulitna River Parks Highway Page 22 3. Diversity of habitats and uniquely 5. Unfettered views of the open sky adapted vegetation • Aurora Borealis/Northern Lights • Lake 1787 (alpine lake) • Storms, clouds, and other weather • Alpine Tundra (specially adapted patterns plants, stunted trees) • Sun halos and sun dogs • High Brush (scrub/shrub) • Spruce Forests • Numerous beaver ponds and streams Tangible Cultural Site Features • Sedge meadows and muskegs 1. -

California's Fourteeners

California’s Fourteeners Hikes to Climbs Sean O’Rourke Cover photograph: Thunderbolt Peak from the Paliasde Traverse. Frontispiece: Polemonium Peak’s east ridge. Copyright © 2016 by Sean O’Rourke. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without express permission from the author. ISBN 978-0-98557-841-1 Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Who should read this .......................... 1 1.2 Route difficulty ............................. 2 1.3 Route points .............................. 3 1.4 Safety and preparedness ........................ 4 1.5 Climbing season ............................ 7 1.6 Coming from Colorado ........................ 7 2 Mount Langley 9 2.1 Southwest slope ............................ 10 2.2 Tuttle Creek ............................... 11 3 Mount Muir 16 3.1 Whitney trail .............................. 17 4 Mount Whitney 18 4.1 Whitney trail .............................. 19 4.2 Mountaineer’s route .......................... 20 4.3 East buttress *Classic* ......................... 21 5 Mount Russell 24 5.1 East ridge *Classic* ........................... 25 5.2 South Face ............................... 26 5.3 North Arête ............................... 26 6 Mount Williamson 29 6.1 West chute ............................... 30 7 Mount Tyndall 31 7.1 North rib ................................ 32 7.2 Northwest ridge ............................ 32 8 Split Mountain 36 8.1 North slope ............................... 37 i 8.2 East Couloir .............................. 37 8.3 St. Jean Couloir -

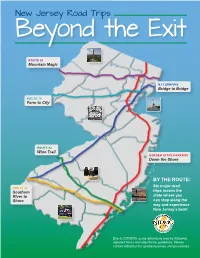

Beyond the Exit

New Jersey Road Trips Beyond the Exit ROUTE 80 Mountain Magic NJ TURNPIKE Bridge to Bridge ROUTE 78 Farm to City ROUTE 42 Wine Trail GARDEN STATE PARKWAY Down the Shore BY THE ROUTE: Six major road ROUTE 40 Southern trips across the River to state where you Shore can stop along the way and experience New Jersey’s best! Due to COVID19, some attractions may be following adjusted hours and attendance guidelines. Please contact attraction for updated policies and procedures. NJ TURNPIKE – Bridge to Bridge 1 PALISADES 8 GROUNDS 9 SIX FLAGS CLIFFS FOR SCULPTURE GREAT ADVENTURE 5 6 1 2 4 3 2 7 10 ADVENTURE NYC SKYLINE PRINCETON AQUARIUM 7 8 9 3 LIBERTY STATE 6 MEADOWLANDS 11 BATTLESHIP PARK/STATUE SPORTS COMPLEX NEW JERSEY 10 OF LIBERTY 11 4 LIBERTY 5 AMERICAN SCIENCE CENTER DREAM 1 PALISADES CLIFFS - The Palisades are among the most dramatic 7 PRINCETON - Princeton is a town in New Jersey, known for the Ivy geologic features in the vicinity of New York City, forming a canyon of the League Princeton University. The campus includes the Collegiate Hudson north of the George Washington Bridge, as well as providing a University Chapel and the broad collection of the Princeton University vista of the Manhattan skyline. They sit in the Newark Basin, a rift basin Art Museum. Other notable sites of the town are the Morven Museum located mostly in New Jersey. & Garden, an 18th-century mansion with period furnishings; Princeton Battlefield State Park, a Revolutionary War site; and the colonial Clarke NYC SKYLINE – Hudson County, NJ offers restaurants and hotels along 2 House Museum which exhibits historic weapons the Hudson River where visitors can view the iconic NYC Skyline – from rooftop dining to walk/ biking promenades. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air Canada (Alberta – VE6/VA6) Association Reference Manual (ARM) Document Reference S87.1 Issue number 2.2 Date of issue 1st August 2016 Participation start date 1st October 2012 Authorised Association Manager Walker McBryde VA6MCB Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged Page 1 of 63 Document S87.1 v2.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) 1 Change Control ............................................................................................................................. 4 2 Association Reference Data ..................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Programme derivation ..................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 General information .......................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Rights of way and access issues ..................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Maps and navigation .......................................................................................................................... 9 2.5 Safety considerations .................................................................................................................. -

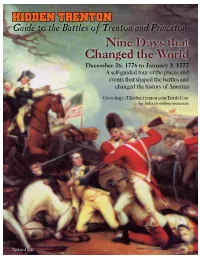

Guide to the Battles of Trenton and Princeton

Hidden Trenton Guide to the Battles of Trenton and Princeton Nine Days that Changed the World December 26, 1776 to January 3, 1777 A self-guided tour of the places and events that shaped the battles and changed the history of America Go to http://HiddenTrenton.com/BattleTour for links to online resources Updated 2017 Copyright © 2011, 2017 all rights reserved. The pdf file of this document may be distributed for non- commercial purposes over the Internet in its original, complete, and unaltered form. Schools and other non-profit educational institutions may print and redistribute sections of this document for classroom use without royalty. All of the illustrations in this document are either original creations, or believed by the author to be in the public domain. If you believe that you are the copyright holder of any image in this document, please con- tact the author via email at [email protected]. Forward I grew up in NJ, and the state’s 1964 Tricentennial cel- Recently, John Hatch, my friend and business partner, ebration made a powerful impression on me as a curious organized a “Tour of the Battle of Trenton” as a silent 4th grader. Leutez’ heroic portrait of Washington Cross- auction item for Trenton’s Passage Theatre. He used ing the Delaware was one of the iconic images of that Fischer’s book to research many of the stops, augmenting celebration. My only memory of a class trip to the park his own deep expertise concerning many of the places a year or two later, is peering up at the mural of Wash- they visited as one of the state’s top restoration architects. -

Wsgs-2002-Gn-74.Pdf (5.967Mb)

WWyyoommiinngg GGeeoo--nnootteess NNuummbbeerr7744 In this issue: Hoback Basin and northern Overthrust Belt 3-D interactive images: Landscapes and Wyoming State Geological Survey landslides Lance Cook, State Geologist The Blue Trail Slide Laramie, Wyoming July, 2002 Wyoming Geo-notes No. 74 July, 2002 Featured Articles Hoback Basin and northern Overthrust Belt . 2 3-D interactive images: Landscapes and landslides . 28 The Blue Trail Slide in the Snake River Canyon . 30 Contents Minerals update ...................................................... 1 Geologic hazards update .................................. 27 Overview............................................................... 1 Highway-affecting landslides of the Snake Calendar of upcoming events ............................ 5 River Canyon–Part III, Blue Trail Slide........ 30 Oil and gas update............................................... 6 Publications update .............................................. 34 Coal update......................................................... 13 New publications available from the Coalbed methane update.................................. 18 Wyoming State Geological Survey ............... 34 Industrial minerals and uranium update....... 19 Ordering information ........................................ 35 Metals and precious stones update ................. 22 Location maps of the Wyoming State Rock hound’s corner: Calcite and onyx .......... 23 Geological Survey ........................................... 36 Geologic mapping and hazards update ............