The Economic Dimension of Yemeni Unity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Special-Purpose Carrier of Pipe Joints

15JULY1988 MEED 25 Ramazarnanpour Ramazanianpour held talks Denktash. says he is ready for financial aspects of its offer. The group — with the ccfnmerce, heavy and light industry unconditional talks with Greek Cypnot Impreqilo, Cogefar and Gruppo m ministers arid visited the Iranian pavilion at the President George Vassiliou about the Industrie Elettromeccaniche per 24th Algiers international fair. future of the divided island. Impiantl all'Estero (GIE)—plans to start • The Mauntanian towns ot Ak|ou|t and Zouerat In March. Denktash insisted any talks work on the diversionary canal for the dam have received equipment including trucks, must be based on a proposal put forward m September (MEED 24:6:88). trailers, water tanks and tractors from their by UNSecretary-General Javier Perez de Bids for construction of the dam, which Algerian twin towns of Staoueli and Ouenza. Cuellar. The proposal has been reacted will replace the old Esna barrage, were by Greek Cypnots. submitted by 12 international groups in Denktash issued his statement on 6 July December 1986. The field was eventually after a three-day visit to Ankara, where he narrowed to three bidders — the Italian BAHRAIN met Turkey's President Evren and Prime group, Yugoslavia's Energoprojekt, and a Minister TurgutOzal. Canadian consortium of The SWC Group • Bahrain National Gas Company (Banagaa) Vassiliou has refused previous offers to and Canadian International produced 3.2 million barrels a day (b/d) ot Construction Corporation. liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) in 1987. This was meet Denktash on the grounds that the highest daily average since 1979 — its first unacceptable preconditions have been The Italian group brought in Switzerland's year of operations — and 5 percent up on the attached to any meeting. -

Economic Update

Economic Update NBK Economic Research Department I 3 November 2020 Projects > Ensaf Al-Matrouk Research Assistant +965 2259 5366 Kuwait: Project awards pick up in 3Q as [email protected] > Omar Al-Nakib lockdown measures ease Senior Economist +965 2259 5360 [email protected] Highlights The value of project awards increased almost 82% q/q to KD 192 million in 3Q20. Projects awarded were transport and power/water-related; no oil/gas or construction projects were signed. KD 2.1bn worth of awards were penciled in for 2020, however, we expect a smaller figure to materialize. Project awards gather pace in 3Q20, but still fall short of However, with the economy experiencing only a partial recovery expectations so far the projects market is likely to remain subdued; only projects essential to the development plan are likely to be After reaching a multi-year low of KD 106 million in 2Q20, a prioritized. (Chart 3.) quarter that saw business activity heavily impacted by the coronavirus pandemic, the value of project awards increased . Chart 2: Annual project awards nearly 82% q/q in 3Q20 to reach KD 192 million. This is still KD billion, *includes awarded and planned modest by previous standards, however, and is 45% lower than 9 9 the KD 350 million worth of projects approved in in 3Q19. (Chart 8 Transport 8 Power & Water 1). One project award from the Ministry of Public Works’ (MPW), 7 7 accounted for the bulk (86%) of total project awards in the Oil & Gas 6 Construction 6 quarter. 5 Industrial 5 Total projects awarded in 2020 so far stand at KD 866 million 4 4 (cumulative), with about KD 1.3 billion still planned for 4Q20. -

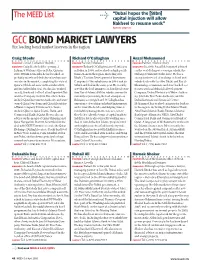

42 MEED Listfinal.Indd

“Dubai hopes the [$8bn] The MEED List Q capital injection will allow Nakheel to resume work” Agenda page 20 GCC BOND MARKET LAWYERS Six leading bond market lawyers in the region Craig Stoehr Richard O’Callaghan Anzal Mohammed POSITION Counsel, Latham & Watkins POSITION Partner, Linklaters POSITION Partner, Allen & Overy BIOGRAPHY Craig Stoehr led the opening of BIOGRAPHY Richard O’Callaghn joined Linklaters BIOGRAPHY In 2009, Anzal Mohammed advised Latham & Watkins office in Doha, Qatar in in Dubai in 2008, and worked on high-profile on the world’s largest sovereign sukuk, the 2008. Within 12 months he had worked on transactions in the region, including Abu Dubai government’s $2bn issue. He has a probably more bond deals by value than any- Dhabi’s Tourism Development & Investment strong track-record of working on bond and one else in the market, completing the state of Company’s $1bn sukuk issue in 2009, and its sukuk deals with the Abu Dhabi and Ras al- Qatar’s $7bn bond issue in November 2009, $1bn bond deal in the same year. He recently Khaimah governments, and state-backed cor- and its earlier $3bn deal. Stoehr also worked acted for the lead arrangers on Saudi real estate porates such as Mubadala Development on a $2.3bn bond for Ras Laffan Liquefied Nat- firm Dar al-Arkan’s $450m sukuk issue and is Company, Dubai Electricity & Water Author- ural Gas Company in 2009. His other clients currently representing the lead arrangers on ity, Jebel Ali Free Zone Authority, and the include Qatar Investment Authority, and state- Bahrain’s sovereign bond. -

Thought Leadership Report GCC LOGISTICS 2017

Thought Leadership Report GCC LOGISTICS 2017 Sponsored By: FOREWORD Mark Geilenkirchen, Chief Executive Officer SOHAR Port and Freezone The office we sit in, the clothes we wear and the food we eat all rely on business planning frameworks that manage material, service, information and capital flows around the globe. This is logistics and by necessity, in today’s increasingly complex business environment, it centres on the communication and control systems required to keep our world moving twenty-four hours a day, each and every day of the year. As one of the world’s fastest growing Port and Freezone developments, logistics is at the core of our business in SOHAR and connects us with markets all over the world. As this is our Year of Logistics, we asked MEED Insight to prepare this special report on the Middle East logistics industry as part of a series of SOHAR sponsored thought leadership reports. We define thought leaders as people or organisations whose efforts are aligned to improve the world by sharing their expertise, knowledge, and lessons learned with others. We believe this knowhow can be the spark behind innovative change, and that’s what we’ve set out to inspire by commissioning this series of reports. 2 GCC LOGISTICS 2016 The GCC Economy GCC Macroeconomic Overview GDP GROWTH GCC VISION PLANS The petrodollar fuelled GCC economies been fairly successful in lowering its oil All the GCC states have formalised strategic, have had a strong run during the first dependency to 42% of GDP in 2014, long- term plans aimed at transforming decade of this millennium, registering a down from 55% in 2008. -

The Dubai Logistics Cluster

THE DUBAI LOGISTICS CLUSTER Alanood Bin Kalli, Camila Fernandez Nova, Hanieh Mohammadi, Yasmin Sanie-Hay, Yaarub Al Yaarubi MICROECONOMICS OF COMPETITENESS COUNTRY OVERVIEW The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is a federation of seven emirates, each governed by its own monarch. The seven Emirates - Abu Dhabi, Ajman, Dubai, Fujairah, Ras al-Khaimah, Sharjah, and Umm al-Quwain - jointly form the Federal Supreme Council, which chooses a president every five years. Since independence from Britain in 1971, the ruler of Abu Dhabi has been elected as the president, while the ruler of Dubai has been elected as the Vice President and Prime Minister. Abu Dhabi serves as the capital and each emirate enjoys a high degree of autonomy. The country is strategically located in the Middle East, bordering the Persian Gulf, the Arabian Sea, Oman and Saudi Arabia. It occupies a total area of 83,600 km2 with around 1,318 km of coastline1. The population is estimated to be 9.3 million in 2015 with only 13% nationals2. UAE Economic Performance The UAE is an oil rich country, with most of its oil and gas production coming from Abu Dhabi. The country was ranked eighth worldwide in terms of oil and gas production in 2012 and seventh in terms of reserves3. Since the UAE’s establishment, oil revenues have been used strategically to develop basic infrastructure and provide UAE citizens with government services including subsidized utilities, free education, and medical services. As a result of oil price fluctuation, the country has understood the importance of diversifying away from this resource and started to develop its petrochemical sector. -

MEED Industry Special Reports 2021

2021-22 Navigate the Middle East The worlds leading source of Middle East business intelligence Launched on International Women’s Day 1957, MEED is a well-known and trusted brand that is used by governments and businesses operating in the region. MEED is a business intelligence service covering the Middle East and North Africa. MEED.com provides daily exclusive news, data and analysis that keeps its subscribers informed about what is going on in the region. Your essential partner for business in the Middle East Supports your planning MEED keeps you up to and decision making date with the region MEED explains changing client needs and policies MEED helps you understand the Middle East Helps you identify new Allows you to track business opportunities your competitors Helps you to identify Supports research challenges and mitigate risks and analysis Unrivalled premium service for business in the Middle East Unique 25-year Archive of Over Middle East Business Newsletters 7,000 direct to your articles published every year inbox MENA MENA MENA economic companies deals indicators database database 60exclusive news and analysis articles a week Access to MEED’s exclusive MENA MENA Middle East city profiles economics market databases 80tender announcements every week MEED Business Review MEED Business Review is the magazine of MEED. It provides MEED subscribers with a monthly report on the Middle East that keeps them informed about what is going on in the region. Delivered in a convenient and beautifully designed format, MEED Business Review is a premium resource curated to help everybody who needs to understand the Middle East. -

Gender and Migration in Arab States

International Labour Organisation GENDER AND MIGRATION IN ARAB STATES: THE CASE OF DOMESTIC WORKERS Edited by Simel Esim & Monica Smith June 2004 Regional Office for Arab States, Beirut International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the of its frontiers. The responsibility for opinions expressed in this study rests solely on the authors and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Office of opinions expressed in them. For more information, please contact: Simel Esim Gender & Women Workers’ Specialist Tel: 961 - 1 - 752400 Fax: 961 - 1 - 752405 Email: [email protected] 4 Gender & Migration in Arab States : The Case of Domestic Workers Foreword Domestic workers, the majority of whom are women, constitute a large portion of today's migrant worker population. As part of the international trend of feminization of international labour, much of this work remains invisible in national statistics and national labour legislation. It is not certain whether the increasing participation of women in international migration provides them with a decent wage, good working conditions, social security coverage and labour protection. It is therefore important to provide more attention to the labour situation of the growing number of women migrant workers. To identify critical issues of concern to women migrant domestic workers and to determine the extent of their vulnerability, the ILO has been analyzing the situation in several regions. These studies reveal practices and patterns that are the key causes of the vulnerability of women domestic migrant workers and suggest effective alternative strategies. This publication presents an ILO regional review and four country studies from the Arab States: Bahrain, Kuwait, Lebanon and United Arab Emirates. -

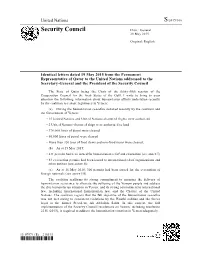

Security Council Distr.: General 20 May 2015

United Nations S/2015/360 Security Council Distr.: General 20 May 2015 Original: English Identical letters dated 19 May 2015 from the Permanent Representative of Qatar to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council The State of Qatar being the Chair of the thirty-fifth session of the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf, I write to bring to your attention the following information about humanitarian efforts undertaken recently by the coalition to restore legitimacy in Yemen: (a) During the humanitarian ceasefire initiated recently by the coalition and the Government of Yemen: • 15 United Nations and United Nations-chartered flights were authorized • 2 United Nations-chartered ships were authorized to land • 370,000 litres of diesel were cleared • 50,000 litres of petrol were cleared • More than 320 tons of food items and non-food items were cleared; (b) As at 15 May 2015: • 431 permits had been issued for humanitarian relief and evacuation (see annex I) • 83 evacuation permits had been issued to international relief organizations and other entities (see annex II); (c) As at 16 May 2015, 306 permits had been issued for the evacuation of foreign nationals (see annex III). The coalition reaffirms its strong commitment to ensuring the delivery of humanitarian assistance to alleviate the suffering of the Yemeni people and address the dire humanitarian situation in Yemen, and its strong commitment to international law, including international humanitarian law, and the Charter of the United Nations. The coalition regrets that the full objective of the humanitarian ceasefire was not met owing to consistent violations by the Houthi militias and the forces loyal to the former President, Ali Abdullah Saleh. -

GCC Projects Overview

GCC Projects Overview A briefing to MEED Projects Customers Abu Dhabi, 19 November 2012 Headlines Baghdad approves $118bn draft budget for 2013 – MEED 5 Nov Saudi Arabia's king appoints new interior minister – BBC, 5 Nov UN: Iran not cooperating on nuclear probe – Daily Star, 5 Nov Bahrain bomb blasts kill two foreign workers – BBC, 5 Nov Syria opposition groups hold Qatar meeting – MEED, 4 Nov UAE approves deficit-free budget for 2013 – MEED, 31 Oct IMF warns GCC to cut government spending – MEED, 30 Nov Adviser lined up for NWC privatisation – MEED, 30 Oct Kuwait awards $2.6bn Subiya Causeway contract – MEED, 29 Oct Contractors submit bids for Doha Metro Red Line - MEED 16 Oct Kuwait approves $433m worth of road projects – MEED, 10 Oct The economic outlook (IMF) Real GDP growth forecast for 2012 and 2013 (%) - IMF • Regionally/globally, outlook is uncertain 10.0 • Global outlook worsened, although emerging economies 8.0 have performed well 6.0 • MENA disrupted by upheaval, but high oil prices boost oil exporters 4.0 • IMF forecasting MENA growth of 2.0 5.3% in 2012, downturn in 2013 • Oil price outlook - $110 barrel in 0.0 2012 and $94/barrel in 2013, up 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 from $104/barrel in 2011 and -2.0 $79/barrel in 2010 -4.0 • GCC growth = 5.3% in 2012 (3.9.% (oil), 6.4% (non oil)) -6.0 World Advanced economies Emerging economies • MENA oil exporters = 5.5% MENA GCC MENA oil importers • MENA oil importers = 2.2% UAE • Iraq = 10.2% (14.7% in 2013) Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2012 The risks to -

The Mineral Industry of the United Arab Emirates in 2014

2014 Minerals Yearbook UNITED ARAB EMIRATES U.S. Department of the Interior December 2017 U.S. Geological Survey THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF THE UNITED ARAB EMIRATES By Waseem A. Abdulameer and Mowafa Taib In 2014, the United Arab Emirates (UAE)1 continued to be Government Policies and Programs a regional industrial center and a global trade and financial hub. Revenue from the country’s large hydrocarbon sector As of yearend 2014, the UAE did not have a specific, was supplemented with revenue from downstream mineral comprehensive Federal law covering the mining industry. The industries. The UAE was the world’s fourth-ranked producer Abu Dhabi Emirate, which is the largest of the UAE’s seven of primary aluminum after China, Russia, and Canada, and Emirates in terms of land area, controlled 94% of the UAE’s accounted for 4.6% of the total global output in 2014. The UAE national oil and gas reserves; the Dubai Emirate controlled 4% was a major regional producer of industrial minerals and metals, of the national oil and gas reserves, and combined the other five including cement, iron and steel, and nitrogen fertilizers. In Emirates controlled the remaining 2%. Article 23 of the UAE 2014, the country was the world’s ninth-ranked direct-reduced Federal Constitution considers each Emirate responsible for iron (DRI) producer. The UAE was also the world’s 11th-ranked managing its own natural resources, including oil and natural sulfur producer and accounted for about 2.7% of the world’s gas. The Supreme Petroleum Council (SPC) regulates the total in 2014. -

Managers' Perception of Corporate Social Responsibility

Managers’ Perception of Corporate Social Responsibility: Evidence from Least Developed Country Managers’ Perception of Corporate Social Responsibility: Evidence from Least Developed Country تصور المديرين للمسؤولية اﻻجتماعية للشركات.. أدلة من البلدان اﻷقل نموا D.Nahg Abdul Majid Alawi D. Abdullah Masood D. Khaled Salmen Aljaaidi Faculty of Economics Faculty of Administrative science Hadhramout University University of Aden University of Aden [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract : This study examines the CSR perception in one of the least develped countries, named; Yemen. The present study contributes to the CSR literature by investigating the level of CSR perception in 73 most active shareholding companies registered in Yemen. A survey questionnaire was used to collect data from CEOs, CFOs, marketing/public relations managers and philanthropy/ CSR managers regarding the determination of the level of CSR perception. The main result concluded by this study is that managers have high degrees of CSR perception. The study has bridged the literature gaps in such that it offers empirical evidence and new insights on CSR body of knowledge which could be used to further improvement of the CSR perception amongst companies in Yemen and similar economies. Keywords: CSR, CSR perception,. management ,Yemen الملخص: تبحث هذه الدراسة تصور املسؤولية اﻻجتماعية للشركات يف واحدة من البلدان اﻷقل منوا ) اليمن(. تساهم هذه الدراسة يف أدبيات املسؤولية اﻻجتماعية للشركات وذلك من خﻻل التحقيق يف مستوى إدراك املسؤولية اﻻجتماعية للشركات يف 27 شركة مسامهة مينيه أكثر نشاطا. وقدمت استخدام استبيان استقصائي جلمع البيانات من املدراء التنفيذيني واملدير املايل ومدراء التسويق / العﻻقات العامة و اﻷعمال اخلريية / مدراء املسؤولية اﻻجتماعية للشركات فيما يتعلق بتحديد مستوى إدراك املسؤولية اﻻجتماعية للشركات. -

The Political Economy of the Peace Process in a Changing Middle East

UNU World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU/WIDER) World Development Studies 8 The Political Economy of the Peace Process in a Changing Middle East Moustafa Ahmed Moustafa UNU World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU/WIDER) A research and training centre of the United Nations University The Board of UNU/WIDER Philip Ndegwa Sylvia Ostry Maria de Lourdes Pintasilgo, Chairperson Antti Tanskanen George Vassiliou Ruben Yevstigneyev Masaru Yoshitomi Ex Officio Heitor Gurgulino de Souza, Rector of UNU Mihaly Simai, Director of UNU/WIDER UNU World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU/WIDER) was established by the United Nations University as its first research and training centre and started work in Helsinki, Finland, in 1985. The principal purpose of the Institute is policy-oriented research on the main strategic issues of development and international cooperation, as well as on the interaction between domestic and global changes. Its work is carried out by staff researchers and visiting scholars in Helsinki and through networks of collaborating institutions and scholars around the world. UNU World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU/WIDER) Katajanokanlaituri 6 B 00160 Helsinki, Finland Copyright © UNU World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU/WIDER) Cover illustration by Jouko Vatanen Camera-ready typescript prepared by Liisa Roponen at UNU/WIDER Printed at Hakapaino Oy, 1996 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s). Publication does not imply endorsement