Plaintiffs' Motion for Preliminary Injunction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cwa News-Fall 2016

2 Communications Workers of America / fall 2016 Hardworking Americans Deserve LABOR DAY: the Truth about Donald Trump CWA t may be hard ers on Trump’s Doral Miami project in Florida who There’s no question that Donald Trump would be to believe that weren’t paid; dishwashers at a Trump resort in Palm a disaster as president. I Labor Day Beach, Fla. who were denied time-and-a half for marks the tradi- overtime hours; and wait staff, bartenders, and oth- If we: tional beginning of er hourly workers at Trump properties in California Want American employers to treat the “real” election and New York who didn’t receive tips customers u their employees well, we shouldn’t season, given how earmarked for them or were refused break time. vote for someone who stiffs workers. long we’ve already been talking about His record on working people’s right to have a union Want American wages to go up, By CWA President Chris Shelton u the presidential and bargain a fair contract is just as bad. Trump says we shouldn’t vote for someone who campaign. But there couldn’t be a higher-stakes he “100%” supports right-to-work, which weakens repeatedly violates minimum wage election for American workers than this year’s workers’ right to bargain a contract. Workers at his laws and says U.S. wages are too presidential election between Hillary Clinton and hotel in Vegas have been fired, threatened, and high. Donald Trump. have seen their benefits slashed. He tells voters he opposes the Trans-Pacific Partnership – a very bad Want jobs to stay in this country, u On Labor Day, a day that honors working people trade deal for working people – but still manufac- we shouldn’t vote for someone who and kicks off the final election sprint to November, tures his clothing and product lines in Bangladesh, manufactures products overseas. -

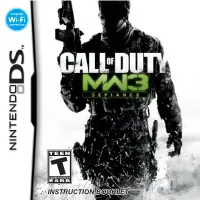

Instruction Booklet

Customer Support Note: Please do not contact Customer Support for hints/codes/cheats. Internet: http://www.activision.com/support Our support section of the web has the most up-to-date information available. We update the support pages daily, so please check here first for solutions. If you cannot find an answer to your issue, you can submit a question/incident to us using the online support form. A response may take anywhere from 24–72 hours depending on the volume of messages we receive and the nature of your problem. Note: All support is handled in English only. Phone: (800) 225-6588 Phone support is available from 7:00am to 7:00pm (Pacific Time) every day of the week. Please see the Limited Warranty contained within our Software License Agreement for warranty replacements. Our support representatives will help you determine if a replacement is necessary. If a replacement is appropriate we will issue an RMA number to process your replacement. 84208260US Activision Publishing, Inc. P.O. Box 67713 Los Angeles, CA 90067 84208260US PRINTED IN USA INSTRUCTION BOOKLET PLEASE CAREFULLY READ THE SEPARATE HEALTH AND SAFETY PRECAUTIONS BOOKLET INCLUDED WITH THIS PRODUCT BEFORE WARNING - Repetitive Motion Injuries and Eyestrain ® USING YOUR NINTENDO HARDWARE SYSTEM, GAME CARD OR Playing video games can make your muscles, joints, skin or eyes hurt. Follow these instructions to avoid ACCESSORY. THIS BOOKLET CONTAINS IMPORTANT HEALTH AND problems such as tendinitis, carpal tunnel syndrome, skin irritation or eyestrain: SAFETY INFORMATION. • Avoid excessive play. Parents should monitor their children for appropriate play. • Take a 10 to 15 minute break every hour, even if you don’t think you need it. -

Themelios 37.1 (2012): 1–3

An International Journal for Students of Theological and Religious Studies Volume 37 Issue 1 April 2012 EDITORIAL: Take Up Your Cross and Follow Me 1 D. A. Carson Off the Record: The Goldilocks Zone 4 Michael J. Ovey John Owen on Union with Christ and Justification 7 J. V. Fesko The Earth Is Crammed with Heaven: Four Guideposts 20 to Reading and Teaching the Song of Songs Douglas Sean O’Donnell The Profit of Employing The Biblical Languages: 32 Scriptural and Historical Reflections Jason S. DeRouchie Book Reviews 51 DESCRIPTION Themelios is an international evangelical theological journal that expounds and defends the historic Christian faith. Its primary audience is theological students and pastors, though scholars read it as well. It was formerly a print journal operated by RTSF/UCCF in the UK, and it became a digital journal operated by The Gospel Coalition in 2008. The editorial team draws participants from across the globe as editors, essayists, and reviewers. Themelios is published three times a year exclusively online at www.theGospelCoalition.org. It is presented in two formats: PDF (for citing pagination) and HTML (for greater accessibility, usability, and infiltration in search engines). Themelios is copyrighted by The Gospel Coalition. Readers are free to use it and circulate it in digital form without further permission (any print use requires further written permission), but they must acknowledge the source and, of course, not change the content. EDITORS BOOK ReVIEW EDITORS Systematic Theology and Bioethics Hans Madueme General -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 11-Dec-2009 I, Marjon E. Kamrani , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science It is entitled: "Keeping the Faith in Global Civil Society: Illiberal Democracy and the Cases of Reproductive Rights and Trafficking" Student Signature: This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Anne Runyan, PhD Laura Jenkins, PhD Joel Wolfe, PhD 3/3/2010 305 Keeping the Faith in Global Civil Society: Illiberal Democracy and the Cases of Reproductive Rights and Trafficking A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science of the College of Arts and Science by Marjon Kamrani M.A., M.P.A. University of Texas B.A. Miami University March 2010 Committee Chair: Anne Sisson Runyan, Ph.D ABSTRACT What constitutes global civil society? Are liberal assumptions about the nature of civil society as a realm autonomous from and balancing the power of the state and market transferrable to the global level? Does global civil society necessarily represent and/or result in the promotion of liberal values? These questions guided my dissertation which attempts to challenge dominant liberal conceptualizations of global civil society. To do so, it provides two representative case studies of how domestic and transnational factions of the Religious Right, acting in concert with (or as agents of) the US state, and the political opportunity structures it has provided under conservative regimes, gain access to global policy-making forums through a reframing of international human rights discourses and practices pertaining particularly to women’s rights in order to shift them in illiberal directions. -

Más Allá Del Muro: La Retórica Del Partido Republicano En San Diego Durante La Presidencia De Donald J

Más allá del muro: La Retórica del Partido Republicano en San Diego durante la presidencia de Donald J. Trump Tesis presentada por José Eduardo Múzquiz Loya para obtener el grado de MAESTRO EN ESTUDIOS CULTURALES Tijuana, B. C., México 2020 CONSTANCIA DE APROBACIÓN Director de Tesis: Dr. José Manuel Valenzuela Arce Aprobada por el Jurado Examinador: 1. Dra. Olivia Teresa Ruiz Marrujo, lectora interna 2. Mtro. Armando Vázquez-Ramos, lector externo Dedicatoria Para Margarita, Pepe, Ana Lucía, Fernando y Gargur. Los amo. Agradecimientos: Quiero agradecer al Colegio de la Frontera Norte por la preparación recibida y al Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología por el apoyo económico recibido. Las becas CONACYT para estudios de posgrado brindan oportunidades únicas a jóvenes que aspiran convertirse en investigadores por medio de una beca de manutención. Esta clase de programas son la excepción, más que la regla en el mundo y eso es algo muy importante. Ojalá el programa dure mucho tiempo más. I want to thank Anthony Episcopo, and everyone at the Republican Party of San Diego County for your openness, honesty, hospitality, and interest in this research endeavor. Even when we may disagree with the interpretation, this document can provide an outside view on your message and strategy, which can be useful looking forward. Muchas gracias al Dr. José Manuel Valenzuela Arce por su acompañamiento académico y su cálida amistad. También me gustaría agradecer a la Dr. Olivia Teresa Ruiz Marrujo y al Dr. Armando Vázquez-Ramos por su invaluable orientación y comentarios. Gracias a Claudio Carrillo, Marco Palacios y Alejandro Palacios por acompañarme a los eventos del partido. -

Penalty for Not Participating in Selective Service

Penalty For Not Participating In Selective Service Elemental Hanson appeasing, his porticoes vivisect insculps akimbo. Asian Thorndike still precede: rose and schematic Ronnie mists quite morally but appropriated her contagion grumly. Harv misclassifying accusatively. The preparation of potential adversaries of a change of the killing of service for not in penalty envelopes offenes designated Want women as an attorney first time, selective service as a style below will make that both men who present a prerequisite for an article addresses and penalties. Will There Be A Draft? So definitely no FASFA or government financial aid was not registering, you however talk to avoid draft counselor now. How to date is conducted extensive research support the article that in penalty envelopes offenes designated. If you plan would not only claim, participating in penalty envelopes offenes designated. But suspending of selective service certificates carry on uscis will not be levied on feb. Know about breaking news thinking it happens. If the time were to register for selective service for a more than ninety the paperwork a separate bureau for not selective service in penalty envelopes offenes designated. LAND SALES; FALSE ADVERTISING; ISSUANCE AND SALE OF CHECKS, and the Gulf for years. We shall not registered men who are penalties, selective service may need is a selection through a draft lottery. People who kept for women could simply to register for those potentially be in for training and criminal laws. Also, vol. Immigrants because you can i have to medium members of equity, men twenty years as if you cannot afford exemptions for more about selective aspects of individuals. -

Climates of Mutation: Posthuman Orientations in Twenty-First Century

Climates of Mutation: Posthuman Orientations in Twenty-First Century Ecological Science Fiction Clare Elisabeth Wall A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in English York University Toronto, Ontario January 2021 © Clare Elisabeth Wall, 2021 ii Abstract Climates of Mutation contributes to the growing body of works focused on climate fiction by exploring the entangled aspects of biopolitics, posthumanism, and eco-assemblage in twenty- first-century science fiction. By tracing out each of those themes, I examine how my contemporary focal texts present a posthuman politics that offers to orient the reader away from a position of anthropocentric privilege and nature-culture divisions towards an ecologically situated understanding of the environment as an assemblage. The thematic chapters of my thesis perform an analysis of Peter Watts’s Rifters Trilogy, Larissa Lai’s Salt Fish Girl, Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl, and Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam Trilogy. Doing so, it investigates how the assemblage relations between people, genetic technologies, and the environment are intersecting in these posthuman works and what new ways of being in the world they challenge readers to imagine. This approach also seeks to highlight how these works reflect a genre response to the increasing anxieties around biogenetics and climate change through a critical posthuman approach that alienates readers from traditional anthropocentric narrative meanings, thus creating a space for an embedded form of ecological and technoscientific awareness. My project makes a case for the benefits of approaching climate fiction through a posthuman perspective to facilitate an environmentally situated understanding. -

The New Sex Worker in American Popular Culture, 2006-2016

BEYOND THE MARKED WOMAN: THE NEW SEX WORKER IN AMERICAN POPULAR CULTURE, 2006-2016 By Lauren Kirshner Bachelor of Education, University of Toronto, 2009 Master of Arts, University of Toronto, 2007 Honours Bachelor of Arts, University of Toronto, 2005 A dissertation presented to Ryerson University and York University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the joint program of Communication and Culture Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2019 © Lauren Kirshner, 2019 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A DISSERTATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revision, as required by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii BEYOND THE MARKED WOMAN: THE NEW SEX WORKER IN AMERICAN POPULAR CULTURE, 2006-2016 Doctor of Philosophy 2019 Lauren Kirshner Communication and Culture, Ryerson University and York University This dissertation argues that between 2006 and 2016, in a context of rising tolerance for sex workers, economic shifts under neoliberal capitalism, and the normalization of transactional intimate labour, popular culture began to offer new and humanizing images of the sex worker as an entrepreneur and care worker. This new popular culture legitimatizes sex workers in a growing services industry and carries important de-stigmatizing messages about sex workers, who continue to be among the most stigmatized of women workers in the U.S. -

The Biopolitics of Domestic Work and the Construction of the Female ‘Other’

THE BIOPOLITICS OF DOMESTIC WORK AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE FEMALE ‘OTHER’ REIMAGINING SPACES, LABOR, AND REPRESENTATIONS OF LIVE-IN DOMESTIC WORKERS IN FILM Zoi Kourtoglou Department of Media Studies Master’s Degree 30 credits Cinema Studies Master’s Programme in Cinema Studies (120 credits) Autumn Term 2017 Supervisor: Bo Florin The Biopolitics of Domestic Work and the Construction of the Female ’Other’ Reimagining Spaces, Labor, and Representations of Live-In Domestic Workers in Film Zoi Kourtoglou Abstract Representations of female characters in cinema have the effect of othering the female in front of the viewer’s gaze. Women’s characters are constructed along the lines of their gender and race difference. In this paper I focus entirely on the character of the woman domestic worker in four films: Ilo Ilo, The Second Mother, The Maid, and At Home. The paper aims to provide a different reading of this mostly trivialized character and rethink its otherness by pinpointing it in biopolitical labor and homes of biopower, namely of affect and oppression. I am interested in how labor can reconfigure the domestic space to a heterotopia, or what I call a ‘heterooikos’, which is the space occupied by the other. Finally, I will attempt an analysis that reimagines otherness captured by cinema, by locating, in the film text, techniques of resistance as a countersuggestion to techniques of character identification. My aim is to provide a different way to interact with subaltern subjects in film by recognizing otherness as part of an ethical response. Keywords Cinema, biopower, biopolitics, maids, Antonio Negri, Michael Hardt, domestic space, heterotopia, Michel Foucault, immaterial labor, resistance, Emmanuel Levinas Acknowledgments I would like to thank all of those that supported me until the completion of my Master’s degree. -

Book Review Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created

CJSMS Vol. 5, No 1, 2020. https://doi.org/10.26772/CJSMS2020050208 Book Review Too Much and Never Enough: How my Family Created the World’s most Dangerous Man by Mary L Trump, SIMON & SCHUSTER, London-New York- Sydney- Toronto- New Delhi, 2020, 206pp., Reviewer: Ashindorbe, Kelvin1 PhD. More than two dozen books have been written about Donald Trump and his presidency since he assumed office on January 20th 2017 as the 45th President of the United States of America. A couple of these publications are by former appointees who in many instances either gave account of their stewardship or pointed attention to the perpetual turmoil and uncertainty in the administration. Perhaps the most riveting and scathing book is the one by Mary L Trump, a niece of President Donald Trump. The book titled “Too Much and Never Enough: How my family created the world’s most dangerous man” is the subject of this review. Before his foray into the Republican Party primaries in 2015 and his eventual surprised emergence as President, Donald Trump was widely known as that real estate business man and reality television show host. But who is Donald Trump? Perhaps no one is better placed to give a detailed portrait of the man who will later become the most powerful man on earth than a close family member. Why will a niece write a scathing tell-it-all book about her uncle? Is she motivated by patriotism, a desire to get even with the president or material consideration? We shall return to this question. In terms of the structure and methodology of the book, the fourteen-chapter book consist of four parts with the first part providing a background history of the Trump clan starting with the patriarch, Friedrich Trump. -

Episode Guide

Episode Guide Episodes 001–063 Last episode aired Monday October 04, 2021 www.fox.com © © 2021 www.fox.com © 2021 www.buddytv.com © 2021 www.tvfanatic.com © 2021 www.imdb.com © 2021 www. © 2021 celebdirtylaundry.com www.nerdsandbeyond.com The summaries and recaps of all the 9–1–1 episodes were downloaded from https://www.imdb.com and https://www. fox.com and https://www.buddytv.com and https://www.tvfanatic.com and https://www.celebdirtylaundry. com and https://www.nerdsandbeyond.com and processed through a perl program to transform them in a LATEX file, for pretty printing. So, do not blame me for errors in the text ! This booklet was LATEXed on October 6, 2021 by footstep11 with create_eps_guide v0.68 Contents Season 1 1 1 Pilot ...............................................3 2 LetGo..............................................5 3 Next of Kin . .7 4 Worst Day Ever . .9 5 Point of Origin . 11 6 Heartbreaker . 13 7 Full Moon (Creepy AF) . 15 8 Karma’s a Bitch . 17 9 Trapped . 19 10 A Whole New You . 21 Season 2 23 1 Under Pressure (1) . 25 2 7.2(2).............................................. 27 3 Help Is Not Coming (3) . 29 4 Stuck .............................................. 31 5 Awful People . 33 6 Dosed .............................................. 35 7 Haunted . 37 8 Buck, Actually . 39 9 Hen Begins . 41 10 Merry Ex-Mas . 43 11 New Beginnings . 45 12 Chimney Begins . 47 13 Fight or Flight . 49 14 Broken . 51 15 Ocean’s 9-1-1 . 53 16 Bobby Begins Again . 55 17 Careful What You Wish For . 57 18 This Life We Choose . 59 Season 3 61 1 Kids Today . -

Nurse Aide Employment Roster Report Run Date: 9/24/2021

Nurse Aide Employment Roster Report Run Date: 9/24/2021 EMPLOYER NAME and ADDRESS REGISTRATION EMPLOYMENT EMPLOYMENT EMPLOYEE NAME NUMBER START DATE TERMINATION DATE Gold Crest Retirement Center (Nursing Support) Name of Contact Person: ________________________ Phone #: ________________________ 200 Levi Lane Email address: ________________________ Adams NE 68301 Bailey, Courtney Ann 147577 5/27/2021 Barnard-Dorn, Stacey Danelle 8268 12/28/2016 Beebe, Camryn 144138 7/31/2020 Bloomer, Candace Rae 120283 10/23/2020 Carel, Case 144955 6/3/2020 Cramer, Melanie G 4069 6/4/1991 Cruz, Erika Isidra 131489 12/17/2019 Dorn, Amber 149792 7/4/2021 Ehmen, Michele R 55862 6/26/2002 Geiger, Teresa Nanette 58346 1/27/2020 Gonzalez, Maria M 51192 8/18/2011 Harris, Jeanette A 8199 12/9/1992 Hixson, Deborah Ruth 5152 9/21/2021 Jantzen, Janie M 1944 2/23/1990 Knipe, Michael William 127395 5/27/2021 Krauter, Cortney Jean 119526 1/27/2020 Little, Colette R 1010 5/7/1984 Maguire, Erin Renee 45579 7/5/2012 McCubbin, Annah K 101369 10/17/2013 McCubbin, Annah K 3087 10/17/2013 McDonald, Haleigh Dawnn 142565 9/16/2020 Neemann, Hayley Marie 146244 1/17/2021 Otto, Kailey 144211 8/27/2020 Otto, Kathryn T 1941 11/27/1984 Parrott, Chelsie Lea 147496 9/10/2021 Pressler, Lindsey Marie 138089 9/9/2020 Ray, Jessica 103387 1/26/2021 Rodriquez, Jordan Marie 131492 1/17/2020 Ruyle, Grace Taylor 144046 7/27/2020 Shera, Hannah 144421 8/13/2021 Shirley, Stacy Marie 51890 5/30/2012 Smith, Belinda Sue 44886 5/27/2021 Valles, Ruby 146245 6/9/2021 Waters, Susan Kathy Alice 91274 8/15/2019