Relations of Amber (Jaipur) State with Mughal Court, 1 694-1 744

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

REPORT of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) "1932'

EAST INDIA (CONSTITUTIONAL REFORMS) REPORT of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) "1932' Presented by the Secretary of State for India to Parliament by Command of His Majesty July, 1932 LONDON PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased directly from H^M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses Adastral House, Kingsway, London, W.C.2; 120, George Street, Edinburgh York Street, Manchester; i, St. Andrew’s Crescent, Cardiff 15, Donegall Square West, Belfast or through any Bookseller 1932 Price od. Net Cmd. 4103 A House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online. Copyright (c) 2006 ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. The total cost of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) 4 is estimated to be a,bout £10,605. The cost of printing and publishing this Report is estimated by H.M. Stationery Ofdce at £310^ House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online. Copyright (c) 2006 ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page,. Paras. of Members .. viii Xietter to Frim& Mmister 1-2 Chapter I.—^Introduction 3-7 1-13 Field of Enquiry .. ,. 3 1-2 States visited, or with whom discussions were held .. 3-4 3-4 Memoranda received from States.. .. .. .. 4 5-6 Method of work adopted by Conunittee .. .. 5 7-9 Official publications utilised .. .. .. .. 5. 10 Questions raised outside Terms of Reference .. .. 6 11 Division of subject-matter of Report .., ,.. .. ^7 12 Statistic^information 7 13 Chapter n.—^Historical. Survey 8-15 14-32 The d3masties of India .. .. .. .. .. 8-9 14-20 Decay of the Moghul Empire and rise of the Mahrattas. -

General Awareness Capsule for AFCAT II 2021 14 Points of Jinnah (March 9, 1929) Phase “II” of CDM

General Awareness Capsule for AFCAT II 2021 1 www.teachersadda.com | www.sscadda.com | www.careerpower.in | Adda247 App General Awareness Capsule for AFCAT II 2021 Contents General Awareness Capsule for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ............................................................................ 3 Indian Polity for AFCAT II 2021 Exam .................................................................................................. 3 Indian Economy for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ........................................................................................... 22 Geography for AFCAT II 2021 Exam .................................................................................................. 23 Ancient History for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ............................................................................................ 41 Medieval History for AFCAT II 2021 Exam .......................................................................................... 48 Modern History for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ............................................................................................ 58 Physics for AFCAT II 2021 Exam .........................................................................................................73 Chemistry for AFCAT II 2021 Exam.................................................................................................... 91 Biology for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ....................................................................................................... 98 Static GK for IAF AFCAT II 2021 ...................................................................................................... -

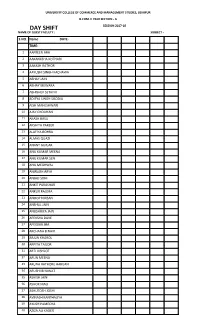

Day Shift Session 2017-18 Name of Guest Faculty : Subject - S.No

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMERCE AND MANAGEMENT STUDIES, UDAIPUR B.COM. II YEAR SECTION - A DAY SHIFT SESSION 2017-18 NAME OF GUEST FACULTY : SUBJECT - S.NO. Name DATE- TIME- 1 AAFREEN ARA 2 AAKANKSHA KOTHARI 3 AAKASH RATHOR 4 AAYUSHI SINGH KACHAWA 5 ABHAY JAIN 6 ABHAY MEWARA 7 ABHISHEK SETHIYA 8 ADITYA SINGH SISODIA 9 AISH MAHESHWARI 10 AJAY CHOUHAN 11 AKASH BASU 12 AKSHITA PAREEK 13 ALAFIYA BOHRA 14 ALMAS QUAZI 15 ANANT GURJAR 16 ANIL KUMAR MEENA 17 ANIL KUMAR SEN 18 ANIL MEGHWAL 19 ANIRUDH ARYA 20 ANJALI SONI 21 ANKIT PARASHAR 22 ANKUR RAJORA 23 ANOOP NIRBAN 24 ANSHUL JAIN 25 ANUSHRIYA JAIN 26 APEKSHA DAVE 27 APEKSHA JHA 28 ARCHANA B NAIR 29 ARJUN KHAROL 30 ARPITA TAILOR 31 ARTI VISHLOT 32 ARUN MEENA 33 ARUNA RATHORE HARIJAN 34 ARUSHI BIYAWAT 35 ASHISH JAIN 36 ASHOK MALI 37 ASHUTOSH JOSHI 38 AVINASH KANTHALIYA 39 AYUSH PAMECHA 40 AZIZA ALI KADER 41 BATUL 42 BHARAT LOHAR 43 BHARAT MEENA 44 BHARAT PURI GOSWAMI 45 BHAVIN JAIN 46 BHAWANA SOLANKI 47 BHUMIKA JAIN 48 BHUMIKA PALIYA 49 BHUMIT SEVAK 50 BHUPENDRA JAIN 51 BINISH KHAN 52 BURHANUDDIN MOOMIN 53 CHANCHAL SOLANKI 54 CHETAN KOTIA 55 DAKSH VYAS 56 DANISH KHAN 57 DARSHIT DOSHI 58 DEEPAK NAGDA 59 DEEPAK SHRIMALI 60 DEEPIKA SAHU 61 DEEPIKA SINGH KHARWAR 62 DEEPIKA YADAV 63 DEEPTI KUMAWAT 64 DHRUVIT KUMAWAT 65 DIKSHANT VAIRAGI 66 DINESH KUMAR MEENA 67 DINESH NAGDA 68 DINESH RAJPUROHIT 69 DIPESH JAIN 70 DIVYA GUPTA 71 DIVYA JAIN 72 DIVYA MALI 73 DIVYA NAKWAL 74 DIVYA SONI 75 DURGA BHATT 76 DURGA SHANKAR MALI 77 FATEMA BOHRA 78 FIRDOSH MANSURI 79 GAJENDRA MENARIA 80 GAJENDRA PUSHKARNA Signature of Guest Faculty DEAN UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMERCE AND MANAGEMENT STUDIES, UDAIPUR B.COM. -

Robert's Roughguide to Rajasthan

Robert’s Royal Rajasthan Rider’s Roughguide in association with All work herein has been sourced and collated by Robert Crick, a participant in the 2007 Ferris Wheels Royal Rajasthan Motorcycle Safari, from various resources freely available on the Internet. Neither the author nor Ferris Wheels make any assertions as to the relevance or accuracy of any content herein. 2 CONTENTS 1 HISTORY OF INDIA - AN OVERVIEW ....................................... 3 POLITICAL INTRODUCTION TO INDIA ..................................... 4 TRAVEL ADVISORY FOR INDIA ............................................... 6 ABOUT RAJASTHAN .............................................................. 9 NEEMRANA (ALWAR) ........................................................... 16 MAHANSAR ......................................................................... 16 BIKANER ............................................................................ 17 PHALODI ............................................................................ 21 JAISALMER ......................................................................... 23 JODPHUR ........................................................................... 26 PALI .................................................................................. 28 MT ABU .............................................................................. 28 UDAIPUR ............................................................................ 31 AJMER/PUSKAR ................................................................... 36 JAIPUR -

Killer Khilats, Part 1: Legends of Poisoned ªrobes of Honourº in India

Folklore 112 (2001):23± 45 RESEARCH ARTICLE Killer Khilats, Part 1: Legends of Poisoned ªRobes of Honourº in India Michelle Maskiell and Adrienne Mayor Abstract This article presents seven historical legends of death by Poison Dress that arose in early modern India. The tales revolve around fears of symbolic harm and real contamination aroused by the ancient Iranian-in¯ uenced customs of presenting robes of honour (khilats) to friends and enemies. From 1600 to the early twentieth century, Rajputs, Mughals, British, and other groups in India participated in the development of tales of deadly clothing. Many of the motifs and themes are analogous to Poison Dress legends found in the Bible, Greek myth and Arthurian legend, and to modern versions, but all seven tales display distinc- tively Indian characteristics. The historical settings reveal the cultural assump- tions of the various groups who performed poison khilat legends in India and display the ambiguities embedded in the khilat system for all who performed these tales. Introduction We have gathered seven ª Poison Dressº legends set in early modern India, which feature a poison khilat (Arabic, ª robe of honourº ). These ª Killer Khilatº tales share plots, themes and motifs with the ª Poison Dressº family of folklore, in which victims are killed by contaminated clothing. Because historical legends often crystallise around actual people and events, and re¯ ect contemporary anxieties and the moral dilemmas of the tellers and their audiences, these stories have much to tell historians as well as folklorists. The poison khilat tales are intriguing examples of how recurrent narrative patterns emerge under cultural pressure to reveal fault lines within a given society’s accepted values and social practices. -

State-Building and the Management of Diversity in India (Thirteenth to Seventeenth Centuries) Corinne Lefèvre

State-building and the Management of Diversity in India (Thirteenth to Seventeenth Centuries) Corinne Lefèvre To cite this version: Corinne Lefèvre. State-building and the Management of Diversity in India (Thirteenth to Sev- enteenth Centuries). Medieval History Journal, SAGE Publications, 2014, 16 (2), pp.425-447. 10.1177/0971945813514907. halshs-01955988 HAL Id: halshs-01955988 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01955988 Submitted on 7 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Medieval History Journal http://mhj.sagepub.com/ State-building and the Management of Diversity in India (Thirteenth to Seventeenth Centuries) Corinne Lefèvre The Medieval History Journal 2013 16: 425 DOI: 10.1177/0971945813514907 The online version of this article can be found at: http://mhj.sagepub.com/content/16/2/425 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for The Medieval History Journal can be found at: Email Alerts: http://mhj.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://mhj.sagepub.com/subscriptions -

Result Gazette

UNIVERSITY OF JAMMU RESULT GAZETTE B.Ed. Semester-I Examination 2019-21 Held in February 2020 (Errors & Omissions Excepted) PUBLISHED BY: Controller of Examinations University of Jammu Baba Sahib Ambedkar Road Jammu-180006 Date: 21st August 2020 With Best Compliments From Controller of Examinations Re-evaluation Dates With prescribed Fee upto 31-08-2020 With late Fee upto 03-09-2020 The applicants shall submit their Online application forms for re-evaluation by following the below mentioned steps w. e. f. 22-08-2020 : - I. Logon to www.coeju.com II. Click on Re-evaluation of 1st Semester icon, fill up their Roll No. and a pre-filled candidate specific re-evaluation form will pop-up. III. Select the subject(s) in which the candidate is desirous of availing the re- evaluation. IV. The candidates shall submit the prescribed fee through online mode only. V. The candidates are not required to submit the hard copy of the re-evaluation form. VI. The candidates are required to get the print of the receipt for online payment and preserve it for reference. ATTENTION ALL CANDIDATES Candidates wishing to apply for Re-evaluation are advised to conscientiously peruse the below mentioned Statutes before doing so:- 1. The fee for Re-evaluation shall be Rs. 810/- (or as notified from time to time) per answer script for a count of 10 days from the date of declaration of main result (excluding the day of declaration of main result). The form shall also be accepted with a late fee of Rs. 450/- (or as notified from time to time) per answer script for another count of 3 days, Late fee of Rs. -

Jogsanjog.Com Classified Adveritsement Last Updated on :- 1

Jogsanjog.com Classified Adveritsement Last Updated on :- 30 September 2021 DOB, time and birth Education Profession / Salary/Income PM/PA/Occupation Matri id Name Nanihal , Origin Height Father 's information place 'M' if manglik Details MBBS MBBS MD in respiratory Pursuing Stipend Rs 87500 Retired as Chief General Manager from ONGC (38 30 November 1993 , 3 : Dr Vijendrapal Singh Kachwaha Rajput , PM Resident Doctor, MD in Respiratory Medicine (FINAL Years Service). Presently looking own agriculture work 2885 69 10 , Chhattisgarh , Chouhan Uttar Pradesh Year), Dhiraj Hospital, Sumandeep Vidyapeeth, Pipariya, situated at Kalar ka Nagra, Manigaon, Tehsil Saifai, Raipur (C.G.) Vadodara Etawah (UP) 5 August 1992 , 23 : 15 Dr Raghuraj Singh Rawlot Bhati , Andaman Nicobar Islands Institute of Medical Sciences Port 3122 71 , Rajasthan , Khangar Government Teacher Jodha Rajasthan Blair Nagaur 30 April 1992 , Not Dr Devendra Singh Available , Madhya 2428 Rathore , Rajasthan 72 MBBS, MS ( Ear Nose and Throat) , 10 Lakh ENT Surgeon Business Chawda Pradesh , Barnagar ujjain 20 December 1993 , 10 B.PHARMA , Field Officer Kansa, Co.Jalandhar baranch balawat (Rathore) , Senior Teacher (Hindi) Govt High School Siwana 2184 Keshar Partap Dewda 65 : 30 , Rajasthan , Jodhpur (Raj ) Rs 4.00 LPA, Field Officer unimark helth thcare Rajasthan (Barmer) Raj siwana LTD Jodhpur (Raj ) 3 February 1990 , 11 : Dr.Aditya Singh Jhala , Madhya Retired deputy commissioner (ministry of labor and 2866 70 30 , Madhya Pradesh , MBBS - MUHS, nashik MS (ophthalmology)- Jaipur Rathore Pradesh welfare, central government) Ujjain 25 December 1996 , 9 : Dr. Ishmadhu Singh Chouhan/Vats(Gotra) , M.B.B.S. M.B.B.S. Completed In March 2021 and currently 3132 70 15 , Rajasthan , Sawai Manager Baroda Rajasthan Kshetriya Gramin Bank Rajawat Rajasthan preparing for Post Graduation. -

Rajasthan University of Health Sciences, Jaipur B.Sc Nursing Online Entrance Examination 2017 Provisional Marks List

Rajasthan University of Health Sciences, Jaipur B.Sc Nursing Online Entrance examination 2017 Provisional Marks list Marks in State Class 12th Class Class Sl. No Roll No. Form No. Candidate Name Father Name Gender Category PH Dob Online Domicile Attempts 10th % 12th % Exam 1 112974 404293 AACHUKI BHANWAR LAL Female SC RAJ 1 4-May-00 51.83 56.50 33 2 118314 411913 AAFREEN GAURI AFTAB HUSSAIN Female OBCNCL RAJ 1 12-Oct-00 55.67 52.50 30 3 118755 406260 AAFTAB ALI ALVI HABIB SHAH Male OBCNCL RAJ 1 21-Jun-00 52.00 64.50 31 4 111616 408953 AAFTAB KHAN SUBANA KHAN Male OBCNCL RAJ 1 12-Mar-00 72.33 74.75 43 5 118729 404602 AAINA BANO GULAM HUSSAIN BHATI Female OBCNCL RAJ 1 4-Jun-00 64.67 77.25 35 6 116796 414279 AAKANSHA BARIA RAJENDRA BARIA Female ST RAJ 1 15-Dec-98 61.67 70.50 22 7 111092 410727 AAKANSHA BHOI BHARAT LAL BHOI Female OBCNCL RAJ 1 5-Nov-99 72.67 51.25 29 8 123095 408685 AAKASH RAKESH KUMAR Male GEN Others 1 19-Nov-98 70.20 65.25 54 9 111204 402810 AAKASH BOLA RAMCHANDRA Male OBCNCL RAJ 1 13-May-00 71.83 78.50 40 10 120286 400621 AAKASH GEHLOT JITENDRA GEHLOT Male OBCNCL RAJ 1 22-Aug-99 64.17 69.75 34 11 119337 411162 AAKASH KUMAR SHIVCHARAN Male SC RAJ 1 15-May-00 62.33 72.00 30 12 113626 408018 AAKASH KUMAR JANGID SURENDRA KUMAR JANGID Male OBCNCL RAJ 1 16-Jan-98 86.00 81.25 54 13 114930 414800 AAKASH RAO PURUSHOTTAM RAO Male OBCNCL RAJ 1 26-Aug-99 57.57 69.00 44 14 114886 415733 AAKASH VERMA RAJESH KUMAR VERMA Male SC RAJ 2 23-May-98 52.33 79.00 33 15 116465 407718 AAKASH VIJAYVARGIYA RAMBABU VIJAYVARGIYA Male GEN RAJ 1 10-Mar-98 78.00 56.75 51 16 117259 408125 AALIND SEHRAWAT MALIK RAJ Male GEN Others 1 18-May-00 89.30 64.50 43 17 114229 408978 AALISHA DODIYAR HIRALAL Female STA RAJ 1 20-Mar-99 54.67 58.75 35 18 122488 409022 AAMIR KHAN ASRUDEEN Male OBCNCL RAJ 1 16-Mar-99 61.33 70.25 36 19 116803 406538 AAMIR SOHAIL MOH. -

388 22 - 28 February 2008 16 Pages Rs 30

#388 22 - 28 February 2008 16 pages Rs 30 Weekly Internet Poll # 388 Q. How would you describe the Madhes general strike? Total votes: 4,735 Dark Ages hronic shortages of electricity, fuel, water and now food have brought about a serious dislocation of Weekly Internet Poll # 389. To vote go to: www.nepalitimes.com C businesses, trade and livelihoods throughout the country. Q. Given the crisis in the Madhes should the elections be: The shortages come at a time of deepening political crisis in the Madhes in the run-up to elections. They feed the public’s perception of government incompetence. What is surprising is that people are still queuing up for fuel, gas and water without complaining. But public patience is running thin, and relatively minor incidents can spiral out of control as seen last week in Bhaktapur. Photo essay: p 8-9. SAM KANG LI 2 EDITORIAL 22 - 28 FEBRUARY 2008 #388 Published by Himalmedia Pvt Ltd, Editor: Kunda Dixit Design: Kiran Maharjan Director Sales and Marketing: Sunaina Shah marketing(at)himalmedia.com Circulation Manager: Samir Maharjan sales(at)himalmedia.com Subscription: subscription(at)himalmedia.com,5542525/535 Hatiban, Godavari Road, Lalitpur editors(at)nepalitimes.com GPO Box 7251, Kathmandu 5250333/845, Fax: 5251013 www.nepalitimes.com Printed at Jagadamba Press, Hatiban: 5250017-19 A War on Tolerance When the people feel abandoned... AMSTERDAM — When ‘tolerance’ He thinks that Europe is in peril hostile to capital cities. Brussels, becomes a term of abuse in a place of being ‘Islamized’. “There will the capital of the European Union, POWER TO THE PEOPLE like the Netherlands, you know soon be more mosques than stands for everything that Not even if someone wanted to deliberately sabotage the country that something has gone seriously churches,” he says, if true populists, whether left or right, would they be as successful as the Seven Minus One party wrong.