SCOPYRIGHT This Copy Has Been Supplied by the Library of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making Our Own—Two Ethnographies of the Vernacular in New Zealand Music: Tramping Club Singsongs and the Māori Guitar Strumming Style

Making our own—two ethnographies of the vernacular in New Zealand music: tramping club singsongs and the Māori guitar strumming style by Michael Brown A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington/Massey University in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music New Zealand School of Music 2012 ii Abstract This work presents two ethnographies of the vernacular in New Zealand music. The ethnographies are centred on the Wellington region, and deal respectively with tramping club singsongs and the Māori guitar strumming style. As the first studies to be made of these topics, they support an overall argument outlined in the Introduction, that the concept of ―vernacular‖ is a valuable way of identifying and understanding some significant musical phenomena hitherto neglected in New Zealand music studies. ―Vernacular‖ is conceptualised as an informal, homemade approach that enables people to customise music-making, just as language is casually manipulated in vernacular speech. The different theories and applications which contribute to this perspective, taken from music studies and other disciplines, are examined in Chapter 1. A review of relevant New Zealand music literature, along with a methodological overview of the ethnographies is presented in Chapter 2. Each study is based upon different mixtures of techniques, including participant-observer fieldwork, oral history, interviews, and archival research. They can be summarised as follows: Tramping club singsongs: a medium of informal self-entertainment among New Zealand wilderness recreationists in the mid-twentieth century. The ethnography focuses on two clubs in the Wellington region, the Tararua Tramping Club and the Victoria University College Tramping Club, during the 1940s-1960s period, when changing social mores, tramping‘s camaraderie and individualism, and the clubs‘ different approaches, gave their singsongs a distinctive character. -

The Dunedin Sound: Your Photos Wanted!

e Dunedin Sound – Your photos wanted! Like the memories they capture, they may be blurry, fuzzy and have faded a little with time – but Department of Music senior lecturer Ian Chapman still wants to use your pictures in his latest book. Dr Chapman is writing a book on the music produced by bands such as The Verlaines, The Chills and The Bats from the 1970s to the early 1990s which is now described as the ‘Dunedin Sound’. Dr Chapman hopes to include images taken by former Otago students during the Dunedin Sound’s hey-day, or by those who were at some of the seminal performances. Whether the photos are big, small, black and white, colour, sharp, blurry, digital, or prints – and especially if they are previously unpublished – images will be considered for publication in the book, he says. In return, those who submit images included in the publication will receive a copy of the book. All original photos will be returned to their owners. As well as exploring the bands and the contribution they made to New Zealand music, Dr Chapman says the book will discuss definitions of the Dunedin Sound – the term, for example, is often equated with Flying Nun records, but he points out that not all bands signed to the New Zealand label were based in Dunedin. Dr Chapman has written extensively on the music and career of pop-icon David Bowie and previously performed as “alter-ego” Dr Glam until he retired the character in 2014. He has also written on New Zealand music, with publications on Kiwi 'rock chicks', and most recently, New Zealand glam rock. -

Fiona Hall Medicine Bundle for the Non-Born Child (Detail) 1994

Bulletin Summer Christchurch Art Gallery December 2008 — B.155 Te Puna o Waiwhetu February 2009 1 Bulletin B.155 Summer Christchurch Art Gallery December 2008 — Te Puna o Waiwhetu February 2009 Two cyclists use the custom-designed bikes that form Anne Veronica Janssens's Les Australoïdes installation in the Gallery foyer. Front and back cover images: Fiona Hall Medicine bundle for the non-born child (detail) 1994. Aluminium, rubber, plastic layette comprising matinee jacket. Collection of Queensland Art Gallery, purchased 2000. Queensland Art Gallery Foundation Grant. Courtesy of the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney 2 3 Contents B.155 4 DIRECTOR'S FOREWORD A few words from director Jenny Harper 5 EXHIBITIONS PROGRAMME What's on at the Gallery this season 6 FIONA HALL: FORCE FIELD Paula Savage on one of Australia's finest contemporary artists 15 LOOKING INTO FORCE FIELD Two personal responses 16 SHOWCASE Recent gifts to the Gallery's collection 18 WUNDERBOX A collection of collections from the collection 26 THE ART OF COLLECTING Four artists show us their personal collections 30 LET IT BE NOW Six emerging Canterbury artists 34 WHITE ON WHITE Exploring the myriad possibilities of white 42 OUTER SPACES Richard Killeen takes his art out to the street 44 LONG WIRES IN DARK An interview with MUSEUMS Alastair Galbraith 46 ARE YOU TALKING TO ME? Jim and Mary Barr on collecting 47 PAGEWORK #1 Eddie Clemens 50 TE HURINGA / Pākehā colonisation TURNING POINTS and Māori empowerment 56 SCAPE 2008 Looking back at some of the Gallery projects 58 MY FAVOURITE Film-maker Gaylene Preston makes her choice 60 TIME-LAPSE Installing United We Fall 62 NOTEWORTHY News bites from around the Gallery 64 STAFF PROFILE Martin Young 64 COMING SOON Previewing Rita Angus: Life & Vision and Miles: a life in architecture Please note: The opinions put forward in this magazine are not necessarily those of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu. -

MAKING MAORI AD 1000-1200 1642 1769 ENTER EUROPE 1772 1790S

© Lonely Planet Publications 30 lonelyplanet.com HISTORY •• Enter Europe 31 THE MORIORI & THEIR MYTH History James Belich One of NZ’s most persistent legends is that Maori found mainland NZ already occupied by a more peaceful and racially distinct Melanesian people, known as the Moriori, whom they exterminated. New Zealand’s history is not long, but it is fast. In less than a thousand One of NZ’s foremost This myth has been regularly debunked by scholars since the 1920s, but somehow hangs on. years these islands have produced two new peoples: the Polynesian Maori To complicate matters, there were real ‘Moriori’, and Maori did treat them badly. The real modern historians, James and European New Zealanders. The latter are often known by their Maori Belich has written a Moriori were the people of the Chatham Islands, a windswept group about 900km east of the name, ‘Pakeha’ (though not all like the term). NZ shares some of its history mainland. They were, however, fully Polynesian, and descended from Maori – ‘Moriori’ was their number of books on NZ with the rest of Polynesia, and with other European settler societies, but history and hosted the version of the same word. Mainland Maori arrived in the Chathams in 1835, as a spin-off of the has unique features as well. It is the similarities that make the differences so Musket Wars, killing some Moriori and enslaving the rest (see the boxed text, p686 ). But they TV documentary series interesting, and vice versa. NZ Wars. did not exterminate them. The mainland Moriori remain a myth. -

The Sound of Ruins: Sigur Rós' Heima and the Post

CURRENT ISSUE ARCHIVE ABOUT EDITORIAL BOARD ADVISORY BOARD CALL FOR PAPERS SUBMISSION GUIDELINES CONTACT Share This Article The Sound of Ruins: Sigur Rós’ Heima and the Post-Rock Elegy for Place ABOUT INTERFERENCE View As PDF By Lawson Fletcher Interference is a biannual online journal in association w ith the Graduate School of Creative Arts and Media (Gradcam). It is an open access forum on the role of sound in Abstract cultural practices, providing a trans- disciplinary platform for the presentation of research and practice in areas such as Amongst the ways in which it maps out the geographical imagination of place, music plays a unique acoustic ecology, sensory anthropology, role in the formation and reformation of spatial memories, connecting to and reviving alternative sonic arts, musicology, technology studies times and places latent within a particular environment. Post-rock epitomises this: understood as a and philosophy. The journal seeks to balance kind of negative space, the genre acts as an elegy for and symbolic reconstruction of the spatial its content betw een scholarly w riting, erasures of late capitalism. After outlining how post-rock’s accommodation of urban atmosphere accounts of creative practice, and an active into its sonic textures enables an ‘auditory drift’ that orients listeners to the city’s fragments, the engagement w ith current research topics in article’s first case study considers how formative Canadian post-rock acts develop this concrete audio culture. [ More ] practice into the musical staging of urban ruin. Turning to Sigur Rós, the article challenges the assumption that this Icelandic quartet’s music simply evokes the untouched natural beauty of their CALL FOR PAPERS homeland, through a critical reading of the 2007 tour documentary Heima. -

Hearing Ourselves: Globalisation, the State, Local Content and New Zealand Radio

HEARING OURSELVES: GLOBALISATION, THE STATE, LOCAL CONTENT AND NEW ZEALAND RADIO A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Sociology at the University of Canterbury by Zita Joyce University of Canterbury 2002 ii Abstract _____________________________________________________________________ Local music content on New Zealand radio has increased markedly in the years between 1997, when content monitoring began, and January 2002. Several factors have contributed to this increase, including a shift in approach from musicians themselves, and the influence of a new generation of commercial radio programmers. At the heart of the process, however, are the actions of the New Zealand State in the field of cultural production. The deregulation of the broadcasting industry in 1988 contributed to an apparent decline in local music content on radio. However, since 1997 the State has attempted to encourage development of a more active New Zealand culture industry, including popular music. Strategies directed at encouraging cultural production in New Zealand have positioned popular music as a significant factor in the development and strengthening of ‘national’ or ‘cultural’ identity in resistance to the cultural pressures of globalisation. This thesis focuses on the issue of airtime for New Zealand popular music on commercial radio, and examines the relationship between popular music and national identity. The access of New Zealand popular music to airtime on commercial radio is explored through analysis of airplay rates and other music industry data, and a small number of in-depth interviews with radio programmers and other people active in the industry. A considerable amount of control over the kinds of music supported and produced in New Zealand lies with commercial radio programmers. -

Jorgensen 2019 the Semi-Autonomous Rock Music of the Stones

Sound Scripts Volume 6 | Issue 1 Article 12 2019 The eS mi-Autonomous Rock Music of The tS ones Darren Jorgensen University of Western Australia Recommended Citation Jorgensen, D. (2019). The eS mi-Autonomous Rock Music of The tS ones. Sound Scripts, 6(1). Retrieved from https://ro.ecu.edu.au/soundscripts/vol6/iss1/12 This Refereed Article is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/soundscripts/vol6/iss1/12 Jorgensen: The Semi-Autonomous Rock Music of The Stones The Semi-Autonomous Rock Music of The Stones by Darren Jorgensen1 The University of Western Australia Abstract: The Flying Nun record the Dunedin Double (1982) is credited with having identified Dunedin as a place where independent, garage style rock and roll was thriving in the early 1980s. Of the four acts on the double album, The Stones would have the shortest life as a band. Apart from their place on the Dunedin Double, The Stones would only release one 12” EP, Another Disc Another Dollar. This essay looks at the place of this EP in both Dunedin’s history of independent rock and its place in the wider history of rock too. The Stones were at first glance not a serious band, but by their own account, set out to do “everything the wrong way,” beginning with their name, that is a shortened but synonymous version of the Rolling Stones. However, the parody that they were making also achieves the very thing they set out to do badly, which is to make garage rock. Their mimicry of rock also produced great rock music, their nonchalance achieving that quality of authentic expression that defines the rock attitude itself. -

Dunedin Sound Sources at the Hocken Collections

Reference Guide Dunedin Sound Sources at the Hocken Collections ‘Thanks to NZR Look Blue Go Purple + W.S.S.O.E.S Oriental Tavern 22-23 Feb’, [1985]. Bruce Russell Posters, Hocken Ephemera Collection, Eph-0001-ML-D-07/09. (W.S.S.O.E.S is Wreck Small Speakers on Expensive Stereos). Permission to use kindly granted by Lesley Paris, Norma O’Malley, Denise Roughan, Francisca Griffin, and Kath Webster. Hocken Collections/ Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago Library Nau Mai Haere Mai ki Te Uare Taoka o Hākena: Welcome to the Hocken Collections He mihi nui tēnei ki a koutou kā uri o kā hau e whā arā, kā mātāwaka o te motu, o te ao whānui hoki. Nau mai, haere mai ki te taumata. As you arrive We seek to preserve all the taoka we hold for future generations. So that all taoka are properly protected, we ask that you: place your bags (including computer bags and sleeves) in the lockers provided leave all food and drink including water bottles in the lockers (we have a researcher lounge off the foyer which everyone is welcome to use) bring any materials you need for research and some ID in with you sign the Readers’ Register each day enquire at the reference desk first if you wish to take digital photographs Beginning your research This guide gives examples of the types of material relating to the Dunedin Sound held at the Hocken. All items must be used within the library. As the collection is large and constantly growing not every item is listed here, but you can search for other material on our Online Public Access Catalogues: for books, theses, journals, magazines, newspapers, maps, and audiovisual material, use Library Search|Ketu. -

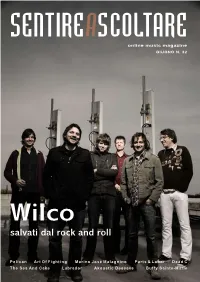

Salvati Dal Rock and Roll

SENTIREASCOLTARE online music magazine GIUGNO N. 32 Wilco salvati dal rock and roll Hans Appelqvist King Kong Laura Veirs Valet Keren Ann Feist Low PelicanStars Of The Art Lid Of Fighting Smog I Nipoti Marino del CapitanoJosé Malagnino Cristina Zavalloni Parts & Labor Billy Nicholls Dead C The Sea And Cake Labrador Akoustic Desease Buffys eSainte-Marie n t i r e a s c o l t a r e WWW.AUDIOGLOBE.IT VENDITA PER CORRISPONDENZA TEL. 055-3280121, FAX 055 3280122, [email protected] DISTRIBUZIONE DISCOGRAFICA TEL. 055-328011, FAX 055 3280122, [email protected] MATTHEW DEAR JENNIFER GENTLE STATELESS “Asa Breed” “The Midnight Room” “Stateless” CD Ghostly Intl CD Sub Pop CD !K7 Nuovo lavoro per A 2 anni di distan- Matthew Dear, uno za dal successo di degli artisti/produt- critica di “Valende”, È pronto l’omonimo tori fra i più stimati la creatura Jennifer debutto degli Sta- del giro elettronico Gentle, ormai nelle teless, formazione minimale e spe- sole mani di Mar- proveniente da Lee- rimentale. Con il co Fasolo, arriva al ds. Guidata dalla nuovo lavoro, “Asa Breed”, l’uomo di Detroit, si nuovo “The Midnight Room”, sempre su Sub voce del cantante Chris James, voluto anche rivela più accessibile che mai. Sì certo, rima- Pop. Registrato presso una vecchia e sperduta da DJ Shadow affinché partecipasse alle regi- ne il tocco à la Matthew Dear, ma l’astrattismo casa del Polesine ed ispirato forse da questa strazioni del suo disco, la formazione inglese usuale delle sue produzioni pare abbia lasciato sinistra collocazione, il nuovo album si districa mette insieme guitar sound ed elettronica, ri- uno spiraglio a parti più concrete e groovy. -

In This Issue: the Art of Flying Nun 01 Being an Urban Artist 02 the Den 03 at the Galleries 03 Place in Time, Tūranga 05 Reviews 08 Ronnie Van Hout 10

Issue 31 Exhibitions Ōtautahi www.artbeat.org.nz August 2021 Galleries Christchurch Studios Waitaha Street Art Canterbury Art in Public Places ARTBEAT In this issue: The Art of Flying Nun 01 Being an Urban Artist 02 The Den 03 At The Galleries 03 Place in Time, Tūranga 05 Reviews 08 Ronnie van Hout 10 Hellzapoppin’! The Art of Flying Nun writer Warren Feeney The opening of Hellzapoppin’! The Art of → Flying Nun Sneaky Feelings in August 2021 at the Christchurch Be My Friend Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū is no coinci- 1982. 7-inch dence. It celebrates to the month, forty years single, designed by Ronnie van ago that Roger Shepherd, then a record Hout store manager in Christchurch established →→ Flying Nun, its first ten years of recording the Tall Dwarfs Slug- predominant subject of a survey exhibition of buckethairy- the original artwork, record covers, posters, breathmonster videos, photographs, design and paintings by 1984. EP Designed by members of the labels’ various bands, musi- Chris Knox cians and associated designers and artists. While debate still fires up among music critics and musicians in Aotearoa about the critical role that Flying Nun played in the post-punk music scene in the 1980s, while Wellington and Auckland saw the emergence of bands that included Beat Rhythm Fashion and The Mockers, (both from Wellington) the anchor of a record label with a distinct attitude and personality has seen Shepherd’s Flying Nun remembered as the sound of that period. Certainly, The Clean, Straitjacket Fits and The Chills are high on the list of bands contributing to such perceptions and memories. -

Te Oro O Te Ao the Resounding of the World

Te Oro o te Ao The Resounding of the World Rachel Mary Shearer 2018 An exegesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Art and Design 1 2 ABSTRACT criteria of ihi—in this context, the intrinsic power of an event that draws a re- sponse from an audience, along with wehi—the reaction from an audience to this intrinsic power, and wana—the aura that occurs during a performance that encompasses both performer and audience, contribute to a series of sound events that aim at evocation or affect rather than interpretable narratives, stories or closed meanings. The final outcome of this research is realised as a sound installation, an exegesis and a 12” vinyl LP. Together these sound practices form a research-led practice document that demonstrates how and why listening to the earth matters, and pro- poses a multi-knowledge framework for understanding sound, space and environ- ment. Nō reira And so Tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou, tēnā tātou katoa Greetings, greetings, greetings to us all Tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou, tēnā tātou katoa Greetings, greetings, greetings to us all This practice-led PhD is a situated Pacific response to international critical dia- logues around materiality in the production and analysis of sonic arts. At the core of this project is the problem of what happens when questions asked in contexts of Pākehā knowledge frameworks are also asked within Māori knowledge frameworks. I trace personal genealogical links to Te Aitanga ā Māhaki, Rongowhakaata and Ngāti Kahungunu iwi. -

Our Contemporary Jewellery Artists Shine at Schmuck

feature Our contemporary jewellery artists shine at Schmuck What has New Zealand jewellery got going for it? Pretty much everything, Philip Clarke explains in this survey of some of our jewellery Olympians and their exploits overseas. chmuck’, the German word, rhymes with book about “the stages of schmuck; denial, anger, acceptance”. and means jewellery. ‘Schmuck’ the Yiddish word In 2017, work by four New Zealand jewellers was ‘S rhymes with yuck and means obnoxious person. selected for Schmuck – five if you include Flora Sekanova, But Schmuck is a jewellery exhibition, the centrepiece of who is now Munich-based. From 700 applications, 66 and shorthand name for the annual Munich Jewellery Week were accepted – and the New Zealand works, by Jane (MJW), described by Damian Skinner as “the Olympics of Dodd, Karl Fritsch, Kelly McDonald, Shelley Norton and ornament, the Venice Biennale of cerebral bling”. Sekanova, represent a stronger showing than the United The global contemporary jewellery calendar is States. Fritsch and Norton have had their work selected coordinated around Schmuck, and about 5000 curators, on multiple occasions and New Zealander Moniek Schrijer collectors, dealers, fans, makers and teachers attend. It’s a won a 2016 Schmuck best-in-show, a coveted Herbert marathon: tribal, fun, important, trivial – and shameless. In Hofmann Prize, as Fritsch has previously. Yet again, it 2014 I was approached at a metro station after midnight by seems, New Zealand is ‘punching above its weight’ – this an attractive young curator who advised, staring intently time in contemporary jewellery. at my Caroline Thomas brooch, that her museum acquired Auckland jeweller Raewyn Walsh has been to MJW “contemporary jewellery by donation”.