Mumbai (Bombay) & Maharashtra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Municipal Co-Operative Bank Ltd.,Mumbai DEAF DATA

The Municipal Co-operative Bank Ltd.,Mumbai DEAF DATA CUSTOMER_NAME ADDRESS DHAR DHONDU DHURI JAIRBAI WADIA RD MUNICIPAL CHAWL NO.92 3RD FLOOR 400012 PAREL,MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA DHAR GANGADHAR BEDEKAR G/S WARD PANDURANG BUDHKAR MARG NULL .,MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA DHAR HANUMANT PATWARDHAN C/202 MINAL CHHAYA CO OP HOS NULL NULL MAHARASHTRA KANT GANPATRAO KENI 750 BLISS APTS 1ST FLOOR ROAD 6 PAVJ I COLONY DADAR 4000014 DADAR,MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA PAD VISHNU DEO 3/32 AHMED SAILOR BLDG DADAR 400014 NULL NULL MAHARASHTRA A AND CDEPARMENT MUMBAI MUMBAI A B PARAB NAGRIK VIKAS SEVA MANDAL PAVWALLA CHAWL NO.5,SAVARKAR NAGARKHAR (E) MUMBAI 400055 A D KAMBLE . NULL NULL MAHARASHTRA A H HYMAVATHI 32/559, KANNAMVAR NAGAR-1 VIKROLI EAST MUMBAI-83 NULL MAHARASHTRA A K RELE MUMBAI MUMBAI A N CHAURASIYA RAM GOVIND STORES MURGIWALA CHAWL, SHOP NO 6, N M JOSHI MARG MUMBAI A S KARAMBELKAR 25/32 IBRAHIM MANSION DR B R AMBEDKAR R D 400012 PAREL,MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA A S SOLANKI . NULL NULL MAHARASHTRA ABBAJI PANDURANG CHUNGLE 16/B VIMAL NIWAS J B MARG 400012 NULL PAREL,MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA ABDON FERNANDES 3/9 MUNICIPAL BLOCK S,V ROAD KHAR MUMBAI ABDUL AHMED ABDUL MATUNGA LABOUR CAMP, TATA POWER HOUSE A-WARD CHAWL NO 2,R.NO 14 MATUNGA MUMBAI 400019 ABDUL BAPU MATUNGA LABOUR CAMP OPP BLDG NO 4 ZOPA DPATTI SHAKA NO 238 MILIND NAGAR 40001 NULL MAHARASHTRA ABDUL J A GAFOOR DHARVAI DONGARI KHANA SION ABDUL KADAR BUZARAT ALI TATA NAGAR ZOPADPATTI GOVANDI STATION,RO OM NO 533 DIVA E,MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA ABDUL MAJID SHAIKH NEW B D D CHAWL NO 21 ROOM NO 61 NAIGAON NULL DAHISAR,MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA ABDUL R BIPAT KADIPUR MOHALLAH JAWAHER NAGAR BADA POST KADIPUR DIST -SULTANPUR U.P. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

Tourism Development for Forts in Maharashtra, India

International Journal of Management, Technology And Engineering ISSN NO : 2249-7455 Modern Project Management for Heritage Conservation: Tourism Development for Forts in Maharashtra, India Dr. Parag Govardhan Narkhede , Prof. Mrudula Darade 1. BKPS College of Architecture, Pune 2. D Y Patil School of Architecture, Charholi, Pune, India ABSTRACT Modern project management techniques are essential for heritage preservation. Implementation of conservation proposals through management is more effective in terms of duration taken and on time completion. The paper deals with the study of forts in Maharashtra Region for the feasibility and potential to develop them as a tourist destination through conservation and preservation. The paper discusses the issues, constraints and potential of tourism in the study area for the future development. And suggest a methodology and guidelines for planning and development of forts considering Eco-Tourism to promote the Tourism activity. Affordability of people is increased due to Globalization and IT Sector, so there is demand for this kind of development. Since there are 350 odd forts in Maharashtra, standing as silent sentinels to history there is a very high Tourism Potential which could develop through the preservation and conservation of the same. Ideal management techniques for the same are to be identified and appropriate recommendations are to be suggested as an outcome of study. 1. INTRODUCTION Tourism in the form of activity influences the regions in which it is developed and received with economic, social, cultural, and environmental dimensions. In most of the development programmers and studies the focus is given only on economic and social dimensions where as environmental dimension is under estimated or ignored. -

Rise of India and the India-Pakistan Conflict

The Rise of India and the India-Pakistan Conflict MANJEET S. PARDESI AND SUMIT GANGULY India is the world's largest democracy and has the fourth-largest econ- omy in terms of purchasing power parity. It is a secular state and has the world's second-largest population. It is also a declared nuclear weapons state with the world's third-largest army and is among the top dozen states in the world in terms of overall defense expenditure. After opening its markets and implementing major structural reforms in its economy after the end of the Cold War, India emerged as one of the fastest-growing economies in the world. In tandem with its economic growth, India has been slowly but surely modernizing its conventional military capabilities as well as its nuclear and missile arsenals. This has led some long-time India-watchers to conclude that India is in the process of becoming a great power. However, India has remained trapped in a conflict with Pakistan-its subcontinental neighbor and rival-ever since the two states were created after the partition of British India in 1947. The two countries have fought four wars since their independence (in 1947-1948, 1965, 1971, and 1999) and have endured many crises during the past 60 years that brought them close to war. In the crises of 1990 and 2001 to 2002, they nearly resorted to the use of nuclear weapons. Pakistan also helped transform the mostly indigenous insurgency in Indian-administered Kashmir that erupted in the late 1980s by providing aid to Islamist terrorist organizations, such as Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) and Jaish-e-Muhammad (eM), which largely replaced the local insurgents. -

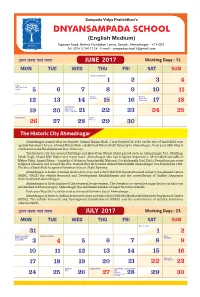

1 Dnynsampada Calender.Cdr

DNYANSAMPADA SCHOOL Tapovan Road, Behind Hundekari Lawns, Savedi, Ahmednagar - 414 003. Tel. (0241) 2411134. E-mail : [email protected] kmZ § ¶ñ¶ ~b § Vñ¶ JUNE 2017 Working Days : 12 MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN Teacher's Reporting X Std Objective Test begins School Parents Reopens Orientation Workshop Longest Day Music Day World Yoga Day Ramzan Eid School Election The Historic City Ahmednagar Ahmednagar named after its founder Ahmad Nizam Shah. I was founded in 1494 on the site of battlefield won against Bahamani forces. Ahmad Nizam Shah established Nizam Shahi Dynasty in Ahmednagar. Each year 28th May is celebrated as the Establishment Day of the city. The historic city has several buildings and sites from Nizam Shahi period such as Ahmednagar fort, Bhistbag, Farah Bagh, Chand Bibi Mahal and many more. Ahmednagar also has religious importance. Meherabad samadhi of Meher Baba. Anand Dham - Samadhi of Acharya Anandrishiji Maharaj, Gorakshanath Gad, Datta Devasthan are some religious places in and around the city. Named after its founder Ahmad Nizam Shah Ahmednagar was founded in 1494. The site of battlefield he against Bahamani forces. Shahi Dynasty. Ahmednagar is home to Indian Armoured corps and school (ACC&S) the Machauised Infautry Regimental centre (MIRC, VRDE) the vehicle Research and Development Establishment and the controllerate of Quality Assurance Vehicles (CQAV) Ahmednagar. Ahmednagar is th birth place of the cooperative movement. The foremost co-operative sugar factory in Asia was established at Pravaranagar, Ahmednagar has maximum number of sugar factories in India. Each year May 28th is celebrated as the establishment day of Ahmednagar. Ahmednagar is home to Indian Armoured corps and school (ACC&S); the Machanised Intantry Regiment at Centre (MIRC), The vehicle Research and Development Establishment (VRDE) and the controllerate of Quality Assurance vehicles (QAV). -

Gcrcbooks 4.Xls Page 1 of 5 15:58 on 22/06/2012 D19 the Cambridge Modern History Volume 02

This is a list of mostly history books from the library of Gervas Clay, who died 18 th April 2009 ( www.spanglefish.com/gervasclay ). Most of them have his bookplate; few have a dust cover. In general they are in good condition, though many covers are faded. Most are hardback; many are first editions. There is another catalogue of his modern books (mostly fiction) which you will find as a WORD document called "Books.doc" in the For Sale section of the Library at http://www.spanglefish.com/gervasclay/library.asp Alas! Though we have only read a few of these, and would love to read more, we just do not have the time. Nor do we have the space to store them. So all of these are BOOKS FOR SALE Box Title Author Publisher Original Publisher Date Edition Comment The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 1 Cambridge UP 1934 Vols. 1 to 10 The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 2 The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 3 The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 4 The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 5 The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 6 D24 The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 7 D23 The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 8 D23 The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 9 D25 The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 10 D24 The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 11 D25 The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 12 D22 Queen Victoria Roger Pulford Collins 1951 No. 2 D21 The Age of Catherine de Medici J.E. Neale Jonathan Cape 1943 1st Edition D22 The two Marshalls, Bezaine & Petain Philip Guedalla Hodder & Stoughton 1943 1st Edition D22 Napoleon and his Marshalls A.G. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX Aodayixike Qingzhensi Baisha, 683–684 Abacus Museum (Linhai), (Ordaisnki Mosque; Baishui Tai (White Water 507 Kashgar), 334 Terraces), 692–693 Abakh Hoja Mosque (Xiang- Aolinpike Gongyuan (Olym- Baita (Chowan), 775 fei Mu; Kashgar), 333 pic Park; Beijing), 133–134 Bai Ta (White Dagoba) Abercrombie & Kent, 70 Apricot Altar (Xing Tan; Beijing, 134 Academic Travel Abroad, 67 Qufu), 380 Yangzhou, 414 Access America, 51 Aqua Spirit (Hong Kong), 601 Baiyang Gou (White Poplar Accommodations, 75–77 Arch Angel Antiques (Hong Gully), 325 best, 10–11 Kong), 596 Baiyun Guan (White Cloud Acrobatics Architecture, 27–29 Temple; Beijing), 132 Beijing, 144–145 Area and country codes, 806 Bama, 10, 632–638 Guilin, 622 The arts, 25–27 Bama Chang Shou Bo Wu Shanghai, 478 ATMs (automated teller Guan (Longevity Museum), Adventure and Wellness machines), 60, 74 634 Trips, 68 Bamboo Museum and Adventure Center, 70 Gardens (Anji), 491 AIDS, 63 ack Lakes, The (Shicha Hai; Bamboo Temple (Qiongzhu Air pollution, 31 B Beijing), 91 Si; Kunming), 658 Air travel, 51–54 accommodations, 106–108 Bangchui Dao (Dalian), 190 Aitiga’er Qingzhen Si (Idkah bars, 147 Banpo Bowuguan (Banpo Mosque; Kashgar), 333 restaurants, 117–120 Neolithic Village; Xi’an), Ali (Shiquan He), 331 walking tour, 137–140 279 Alien Travel Permit (ATP), 780 Ba Da Guan (Eight Passes; Baoding Shan (Dazu), 727, Altitude sickness, 63, 761 Qingdao), 389 728 Amchog (A’muquhu), 297 Bagua Ting (Pavilion of the Baofeng Hu (Baofeng Lake), American Express, emergency Eight Trigrams; Chengdu), 754 check -

Shivaji the Great

SHIVAJI THE GREAT BY BAL KRISHNA, M. A., PH. D., Fellow of the Royal Statistical Society. the Royal Economic Society. London, etc. Professor of Economics and Principal, Rajaram College, Kolhapur, India Part IV Shivaji, The Man and His .Work THE ARYA BOOK DEPOT, Kolhapur COPYRIGHT 1940 the Author Published by The Anther A Note on the Author Dr. Balkrisbna came of a Ksbatriya family of Multan, in the Punjab* Born in 1882, be spent bis boyhood in struggles against mediocrity. For after completing bis primary education he was first apprenticed to a jewel-threader and then to a tailor. It appeared as if he would settle down as a tailor when by a fortunate turn of events he found himself in a Middle Vernacular School. He gave the first sign of talents by standing first in the Vernacular Final ^Examination. Then he joined the Multan High School and passed en to the D. A. V. College, Lahore, from where he took his B. A* degree. Then be joined the Government College, Lahore, and passed bis M. A. with high distinction. During the last part of bis College career, be came under the influence of some great Indian political leaders, especially of Lala Lajpatrai, Sardar Ajitsingh and the Honourable Gopal Krishna Gokhale, and in 1908-9 took an active part in politics. But soon after he was drawn more powerfully to the Arya Samaj. His high place in the M. A. examination would have helped him to a promising career under the Government, but he chose differently. He joined Lala Munshiram ( later Swami Shraddha- Btnd ) *s a worker in the Guruk.ul, Kangri. -

Assistance to the Formulation of the Management Plan for Visitor Centres Under the Ajanta Ellora Conservation and Tourism Development Project (II) in India

Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation, The Republic of India Assistance to the Formulation of the Management Plan for Visitor Centres under the Ajanta Ellora Conservation and Tourism Development Project (II) in India FINAL REPORT August 2010 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. IDO JR 10-002 Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation, The Republic of India Assistance to the Formulation of the Management Plan for Visitor Centres under the Ajanta Ellora Conservation and Tourism Development Project (II) in India FINAL REPORT August 2010 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. PREFACE Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) conducted the Study on the Assistance to the Formulation of the Management Plan for Visitor Centres under the Ajanta Ellora Conservation and Tourism Development Project (II) in the Republic of India, and organized a study team headed by Mr. Yuuichi FUKUOKA of Oriental Consultants Co., Ltd. from March 2010 to August 2010. The study team held a series of discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of India, and conducted several field investigations. As a result of further studies in Japan, the present report was finalized. I hope that this report will contribute to the project and to the enhancement of friendly relations between our two countries. Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the Government of the Republic of India for their close cooperation extended to the study team. August 2010 Shinichi YAMANAKA Chief Representative, JICA India Office Japan International Cooperation Agency SUMMARY SUMMARY 1. General This Summary is based on the main report which covers the findings and Operations and Management plans prepared by the JICA Study Team. -

Sri Lanka India 2018/ 19 & Beyond Featuring the Maldives

SRI LANKA INDIA 2018/ 19 & BEYOND FEATURING THE MALDIVES PRIVATE TOURS ESCORTED TOURS LUXURY TOURS discover unique destinations... RIVER CRUISES MOUNTAIN RETREATS BEACH RETREATS A life of travel is a life well spent Contents SRI LANKA 10-21 PRIVATE TOURS 12-19 SRI LANKA UNCOVERED 12 TRACES OF AN ANCIENT KINGDOM 14 SPLENDOURS OF THE NORTH 15 WILD ABOUT SRI LANKA 16 STUNNING SRI LANKA 18 MOUNTAIN & BEACH RETREATS 20-21 A LUXURY TEA TRAIL 20 BENTOTA 20 TANGALLE 21 TRINCOMALEE 21 SRI LANKA & MALDIVES PRIVATE TOUR 22-23 A TASTE OF SRI LANKA & THE MALDIVES 22 INDIA 24-42 ESCORTED TOUR 26 GOLDEN TRIANGLE 26 PRIVATE TOURS 27-41 GOLDEN TRIANGLE & RANTHAMBORE 27 LUXURY GOLDEN TRIANGLE & UDAIPUR 28 TEMPLES, TAJ & TIGERS 30 SHIMLA TO AMRITSAR 31 RURAL RAJASTHAN 32 COLOURS OF RAJASTHAN 34 GUJARAT TEXTILES, TRIBES & WILDLIFE 35 GOA – SUN, SAND & SPICES 36 MUMBAI & AJANTA CAVES 36 RELAX IN KERALA 37 HIGHLIGHTS OF SOUTH INDIA 38 RIVER CRUISE 40-41 CLASSIC RAJASTHAN & THE SACRED GANGES 40 CITY STAYS 42 SPOTLIGHT ON DELHI 42 SPOTLIGHT ON MUMBAI 42 SPOTLIGHT ON BANGALORE 42 SPOTLIGHT ON CHENNAI 42 TERMS AND CONDITIONS 43 With more than 120 weekly services from Australia, connect seamlessly to India and beyond via the award winning Singapore Changi Airport. Aboard one of the world's most respected airlines, Singapore Airlines guests enjoy unparalleled service and comfort, with gourmet cuisines, hand-selected wines, and state-of-the- art in-flight entertainment. Experience the difference with Singapore Airlines, a great way to fly. WORLD CLASS Service, UNBEATABLE Value & A POSITIVE Social Footprint When you book with Beyond Travel, you’re booking us…our people, our products and our social belief. -

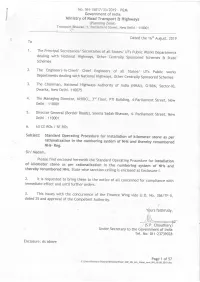

Chief Engineers of At{ States/ Uts Pubtic Works Subject: Stand

p&M n No. NH- 1501 7 / 33 t2A19 - lllnt r Govennment of India $ Ministry of Road Transport & Highways (Ptanning Zone) Transport Bhawan, 1, Partiarnent street, I.{ew Dethi - 110001 Dated the 16th August, 2019 To 1. The PrincipaL secretaries/ secretaries of atl states/ UTs Pubtic Works Departments dealing with National Highways, other centratty Sponsored Schemes & State Schemes 2. Engineers-in-Chief/ The Chief Engineers of at{ States/ UTs pubtic works Departments deating with National Highways, Other Centpatty Sponsored Schemes 3. The Chairman, Nationa[ Highways Authority of India (NHAI), G-5&6, Sector-10, Dwarka, New Dethi- 1rc075 4. The Managing Director, NHIDCL, 3'd Floor, PTI Buitding, 4-parliament Street, New Dethi - 110001 5. Director General (Border Roads), Seema Sadak Bhawan, 4- partiament Street, New Dethi - 1 10001 6. Att CE ROs / SE ROs Subject: Standard Operating Procedure for installation of kilometer stone as per rationalization in the numbering system of NHs and thereby renumbered NHs- Reg. Sir/ Madam, Ptease find enctosed herewith the Standard Operating Procedure for installation of kilometer stone as per rationalization in the numbering system of NHs and thereby renumbered NHs. State wise sanction ceiting is enclosed at Enclosure-;. is 2' lt requested to bring these to the notice of att concerned for comptiance with immediate effect and untiI further orders. 3- This issues with the concurrence of the Finance wing vide u.o. No. 356/TF-ll, dated 25 and approvat of the competent Authority. rs faithfulty, (5.P. Choudhary) Under Secretary to the rnment of India Tet. No. 01 1-23n9A28 f,nctosure: As above Page 1 of 57 c:\users\Hemont Dfiawan\ Desktop\Finat_sop_NH_km*stone*new_l.JH_ l6.0g.2019.doc - No. -

Mumbai Local Sightseeing Tours

Mumbai Local Sightseeing Tours HALF DAY MUMBAI CITY TOUR Visit Gateway of India, Mumbai's principle landmark. This arch of yellow basalt was erected on the waterfront in 1924 to commemorate King George V's visit to Mumbai in 1911. Drive pass the Secretariat of Maharashtra Government and along the Marine Drive which is fondly known as the 'Queen's Necklace'. Visit Jain temple and Hanging Gardens, which offers a splendid view of the city, Chowpatty, Kamala Nehru Park and also visit Mani Bhavan, where Mahatma Gandhi stayed during his visits to Mumbai. Drive pass Haji Ali Mosque, a shrine in honor of a Muslim Saint on an island 500 m. out at sea and linked by a causeway to the mainland. Stop at the 'Dhobi Ghat' where Mumbai's 'dirties' are scrubbed, bashed, dyed and hung out to dry. Watch the local train passing close by on which the city commuters 'hang out like laundry' ‐ a nice photography stop. Continue to the colorful Crawford market and to the Flora fountain in the large bustling square, in the heart of the city. Optional visit to Prince of Wales museum (closed on Mondays). TOUR COST : INR 1575 Per Person The tour cost includes : • Tour in Ac Medium Car • Services of a local English‐speaking Guide during the tour • Government service tax The tour cost does not include: • Entry fees at any of the monuments listed in the tour. The same would be on direct payment basis. • Any expenses of personal nature Note: The above tour is based on minimum 2 persons traveling together in a car.