ED Ophthalmology Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plastics-Roadmap

Oculoplastics Roadmap Idea for New Intern Curriculum Interns should spend at least 1 Friday afternoon in VA Oculoplastics OR; Friday PM is already protected time. Interns should practice 100 simple interrupted stitches and surgeon’s knots in the Wet Lab before PGY2. Lectures (2 hour interactive sessions) Basic Principles of Plastic Surgery and Oculoplastics (Year A = Year B) Trauma Management (Year A: Orbit trauma. Year B: Eyelid trauma.) Eyelid malpositions and dystopias (Year A: Entropion, Ectropion, Ptosis. Year B: spasm, dystonias) Eyelid Lesions: benign and malignant (Year A = Year B) Lacrimal Disorders (Year A: Pediatric. Year B: Adult.) Orbital Disorders (Year A: Acquired. Year B: Congenital.) Core Topics (to be discussed on rotation) Thyroid eye disease management Ptosis evaluation and recommendations Ectropion/entropion management Orbital fracture management Orbit imaging modalities Home Study Topics Orbit anatomy Congenital malformations Surgical steps and instruments Clinical Skills (to be learned on rotation) External photography Lid and orbit measurements Chalazion and lid lesion excisions Punctal plug placement Local anesthetic injection of lids (important for call!) Schirmer Testing, Jones Testing NLD probing/irrigation Canthotomy/cantholysis (in the OR) Directed Reading (residents will read BCSC and article abstracts at home) BCSC Henderson et al. Photographic standards for facial plastic surgery. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2005. Strazar et al. Minimizing the pain of local anesthesia injection. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2013. Simon et al. External levator advancement vs Müller’s muscle–conjunctival resection for correction of upper eyelid involutional ptosis. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2005. Harris and Perez. Anchored flaps in post-Mohs reconstruction of the lower eyelid, cheek, and lateral canthus. -

Online Ophthalmology Curriculum

Online Ophthalmology Curriculum Video Lectures Zoom Discussion Additional videos Interactive Content Assignment Watch these ahead of the assigned Discussed together on Watch these ahead of or on the assigned Do these ahead of or on the Due as shown (details at day the assigned day day assigned day link above) Basic Eye Exam (5m) Interactive Figures on Eye Exam and Eye exam including slit lamp (13m) Anatomy Optics (24m) Day 1: Eye Exam and Eye Anatomy Eyes Have It Anatomy Quiz Practice physical exam on Orientation Anatomy (25m) (35m) Eyes Have It Eye Exam Quiz a friend Video tutorials on eye exam Iowa Eye Exam Module (from Dr. Glaucomflecken's Guide to Consulting Physical Exam Skills) Ophthalmology (35 m) IU Cases: A B C D Online MedEd: Adult Ophtho (13m) Eyes for Ears Podcast AAO Case Sudden Vision Loss Day 2: Acute Vision Loss (30m) Acute Vision Loss and Eye Guru: Dry Eye Ophthalmoscopy and Red Eye Eye Guru: Abrasions and Ulcers virtual module IU Cases: A B C D E Red Eye (30m) Corneal Transplant (2m) Eyes for Ears Podcast AAO Case Red Eye #1 AAO Case Red Eye #2 EyeGuru: Cataract EyeGuru: Glaucoma Cataract Surgery (11m) EyeGuru: AMD Glaucoma Surgery (6m) IU Cases: A B Day 3: Intravitreal Injection (4m) Eyes for Ears Podcast Independent learning Chronic Vision Loss (34m) Chronic Vision Loss AAO Case Chronic Vision Loss reflection (due Day 3 at 8 and and Systemic Disease pm) Systemic Disease (32m) EyeGuru: Diabetic Retinopathy IU Cases: A B Eyes Have It Systemic Disease Quiz AAO Case Systemic Disease #1 AAO Case Systemic Disease #2 Mid-clerkship -

Oculoplastics/Orbit 2017-2019

Academy MOC Essentials® Practicing Ophthalmologists Curriculum 2017–2019 Oculoplastics and Orbit *** Oculoplastics/Orbit 2 © AAO 2017-2019 Practicing Ophthalmologists Curriculum Disclaimer and Limitation of Liability As a service to its members and American Board of Ophthalmology (ABO) diplomates, the American Academy of Ophthalmology has developed the Practicing Ophthalmologists Curriculum (POC) as a tool for members to prepare for the Maintenance of Certification (MOC) -related examinations. The Academy provides this material for educational purposes only. The POC should not be deemed inclusive of all proper methods of care or exclusive of other methods of care reasonably directed at obtaining the best results. The physician must make the ultimate judgment about the propriety of the care of a particular patient in light of all the circumstances presented by that patient. The Academy specifically disclaims any and all liability for injury or other damages of any kind, from negligence or otherwise, for any and all claims that may arise out of the use of any information contained herein. References to certain drugs, instruments, and other products in the POC are made for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to constitute an endorsement of such. Such material may include information on applications that are not considered community standard, that reflect indications not included in approved FDA labeling, or that are approved for use only in restricted research settings. The FDA has stated that it is the responsibility of the physician to determine the FDA status of each drug or device he or she wishes to use, and to use them with appropriate patient consent in compliance with applicable law. -

University of Rochester Flaum Eye Institute

University of Rochester Flaum Eye Institute State-of-the-art eye care… it’s available right here in Rochester. No one should live with vision that is less than what it can be. People who have trouble seeing often accept their condition, not knowing that treatment is available — from the simplest of medications and visual tools to state-of-the-art surgical procedures. Now you can easily refer them to the help they need — all at the Flaum Eye Institute at the University of Rochester. See the dierence we can make in your patients’ quality of life. Refer them today to 585-273-EYES. University of Rochester Flaum Eye Institute A world-class team of ophthalmologists, sub- specialists, and researchers, the faculty practice is committed to developing and applying advanced technologies for the preservation, enhancement, and restoration of vision. Working through a unique partnership of academic medicine, private industry, and the community, we are here to serve you and your patients. One phone number for all faculty practice appoint- ments and new centralized systems make the highest quality eye care more accessible than ever before. Working together, our physicians provide a full range of treatment options for the most common to the most complex vision problems. Glaucoma Cataract Macular Degeneration Diabetic Retinopathy Orbital Diseases Low Vision Dry Eye Syndrome Refractive Surgery Optic Neuropathies Corneal Disease Oculoplastics Motility Disorders Comprehensive Eye Care All-important routine eye exams and a wide range of procedures are oered through the Comprehensive Eye Care service. Consultative, diagnostic, and treatment services are all provided for patients with conditions or symptoms common to cataracts, dry eye, glaucoma, and corneal surface disorders. -

ICO Residency Curriculum 2Nd Edition and Updated Community Eye Health Section

ICO Residency Curriculum 2nd Edition and Updated Community Eye Health Section The International Council of Ophthalmology (ICO) Residency Curriculum offers an international consensus on what residents in ophthalmology should be taught. While the ICO curriculum provides a standardized content outline for ophthalmic training, it has been designed to be revised and modified, with the precise local detail for implementation left to the region’s educators. Download the Curriculum from the ICO website: icoph.org/curricula.html. www.icoph.org Copyright © International Council of Ophthalmology 2016. Adapt and translate this document for your noncommercial needs, but please include ICO credit. All rights reserved. First edition 201 6 . First edition 2006, second edition 2012, Community Eye Health Section updated 2016. International Council of Ophthalmology Residency Curriculum Introduction “Teaching the Teachers” The International Council of Ophthalmology (ICO) is committed to leading efforts to improve ophthalmic education to meet the growing need for eye care worldwide. To enhance educational programs and ensure best practices are available, the ICO focuses on "Teaching the Teachers," and offers curricula, conferences, courses, and resources to those involved in ophthalmic education. By providing ophthalmic educators with the tools to become better teachers, we will have better-trained ophthalmologists and professionals throughout the world, with the ultimate result being better patient care. Launched in 2012, the ICO’s Center for Ophthalmic Educators, educators.icoph.org, offers a broad array of educational tools, resources, and guidelines for teachers of residents, medical students, subspecialty fellows, practicing ophthalmologists, and allied eye care personnel. The Center enables resources to be sorted by intended audience and guides ophthalmology teachers in the construction of web-based courses, development and use of assessment tools, and applying evidence-based strategies for enhancing adult learning. -

2018-2019 Curso De Liderazgo

Pan-American Association of Ophthalmology 2018-2019 Curso de Liderazgo Participant List Dr. Alexandre Antonio Marques Rosa Conselho Brasileiro de Oftalmologia ................................................................................................................................... 1 Dra. Andreia de Faria Martins Rosa* Sociedade Portuguesa de Oftalmologia ................................................................................................................................ 3 Dra. Carla Sabrina Vitelli* Consejo Argentino de Oftalmología ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Dr. Carlos Andrés Wong Morales APTO (Asociación Panamericana de Trauma Ocular) ......................................................................................................... 5 Dra. Claudia Acosta Sociedad Colombiana de Oftalmología ................................................................................................................................ 6 Dr. Francisco Arnalich Montiel Sociedad Española de Oftalmología ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Dr. Gabriel Salomón Lazcano Gomez PAGS (Sociedad Panamericana de Glaucoma) .................................................................................................................... 8 Dr. Jaime Soria Viteri* Sociedad Ecuatoriana de Oftalmología ............................................................................................................................... -

Punctal Stenosis: Definition, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Clinical Ophthalmology Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article REVIEW Punctal stenosis: definition, diagnosis, and treatment Uri Soiberman1 Abstract: Acquired punctal stenosis is a condition in which the external opening of the lacrimal Hirohiko Kakizaki2 canaliculus is narrowed or occluded. This condition is a rare cause of symptomatic epiphora, Dinesh Selva3 but its incidence may be higher in patients with chronic blepharitis, in those treated with various Igal Leibovitch1 topical medications, including antihypertensive agents, and especially in patients treated with taxanes for cancer. The purpose of this review is to cover the medical literature, focusing in 1Division of Oculoplastic and Orbital Surgery, Department of particular on definition, incidence, risk factors, etiology and treatment options. Ophthalmology, Tel-Aviv Medical Keywords: acquired punctal stenosis, definition, epiphora, etiology, treatment Center, Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv, Israel; 2Department of Ophthalmology, Aichi Medical University, Nagakute, Introduction Japan; 3South Australian Institute of Ophthalmology and Discipline of Epiphora is a common complaint encountered by ophthalmologists, with a broad dif- Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, ferential diagnosis. One of the least discussed etiologies of epiphora is stenosis of the University of Adelaide, South Australia, Australia external lacrimal punctum. When it occurs, the most common presenting symptom is tearing, but patients may have vague complaints of ocular discomfort.1 Stenosis must be distinguished from complete occlusion of the puncti, which differs in its treatment and prognosis. This review relates only to punctal stenosis. Anatomically, acquired punctal stenosis is a condition in which the external opening of the lacrimal canaliculus, located in the nasal part of the palpebral margin, is narrowed or occluded. -

Visionamerica of Birmingham

VisionAmerica of Birmingham EYE HEALTH PARTNERS OF ALABAMA AND TENNESSEE TRENTON CLEGHERN, OD, FAAO Our Mission Provide the highest quality of medical and surgical eye care available while advocating the cooperative efforts of optometry and ophthalmology through clinical care, education and research. Multi-specialty medical and surgical eye Care No Primary Care Services Medical eye care Cataract and refractive surgery Cornea surgery Retina Oculoplastics Medical and surgical management of glaucoma Neuro-ophthalmology Pediatrics and strabismus Genetic eye disease and electrophysiological testing VisionAmerica of Birmingham Paul Batson, OD Regional Executive Director Jill Helton, OD Assistant Center Director Trenton Cleghern, OD Consultative Optometrist Rod Nowakowski, OD, PhD Genetic Eye Disease and Electrodiagnostics Donald McCurdy, MD Cataract Surgeon Jeff Fuller, MD Retinal Specialist Irene Ludwig, MD Pediatric and Strabismus Surgeon Matthew Albright, MD Cataract and Cornea Surgeon Dale Brown, MD Retina Specialist Kristin Madonia, MD Neuro-ophthalmologist and Oculoplastics Michael Eddins, MD Cataract Surgeon Anterior Segment/General Medical Eye Care Topical/Clear Cornea Cataract Surgery Same Day Cataract Surgery Toric and Presbyopic IOL’s YAG Capsulotomy Laser Trabeculoplasty Laser Peripheral Iridotomy Pterygium Surgery Uveitis Glaucoma Management Cornea Corneal Ulcers Superficial Keratectomy Intacs for Keratoconus Corneal Transplants Descemet Stripping Endothelial Keratoplasty (DSAEK) Oculoplastics Blepharoplasty Ptosis repair Forehead -

Evisceration in the Modern Age

Review Article Evisceration in the Modern Age Laura T. Phan1,2, Thomas N. Hwang3, Timothy J. McCulley1,2 ABSTRACT Access this article online Website: Evisceration is an ophthalmic surgery that removes the internal contents of the eye www.meajo.org followed usually by placement of an orbital implant to replace the lost ocular volume. DOI: Unlike enucleation, which involves removal of the entire eye, evisceration potentially causes 10.4103/0974-9233.92113 exposure of uveal antigens; therefore, historically there has been a concern about sympathetic Quick Response Code: ophthalmic (SO) associated with evisceration. However, critical review of the literature shows that SO occurs very rarely, if ever, as a consequence of evisceration. Its clinical applications overlap with those of enucleation in cases of penetrating ocular trauma and blind painful eyes, but it is absolutely contraindicated in the setting of suspected intraocular malignancy and may be preferred for treatment of end-stage endophthalmitis. From a technical standpoint, traditional evisceration has a limitation in the orbital implant size. Innovations with scleral modification have overcome this limitation, and accordingly, due to its simplicity, efficiency, and good cosmetic results, evisceration has once again been gaining popularity. Key words: Endophthalmitis, Enucleation, Evisceration, Intraocular Tumors INTRODUCTION While the risk of sympathetic ophthalmia continues to be a contentious issue, evisceration has gained popularity in the visceration (removal of intraocular contents) and enucleation past few decades. This is based largely on the perception E(removal of the entire eye) are competing techniques, with that evisceration provides superior functional and cosmetic fluctuating favor since their inception. Enucleation may be the results compared to enucleation. -

Online Ophthalmology Curriculum

Online Ophthalmology Curriculum Video Lectures Zoom Discussion Additional videos Interactive Content Assignment Watch these ahead of the assigned Discussed together on Watch these ahead of or on the assigned Do these ahead of or on the Due as shown (details at day the assigned day day assigned day link above) Basic Eye Exam (5m) Interactive Figures on Eye Exam and Eye exam including slit lamp (13m) Anatomy Optics (24m) Day 1: Eye Exam and Eye Anatomy Eyes Have It Anatomy Quiz Practice physical exam on Orientation Anatomy (25m) (35m) Eyes Have It Eye Exam Quiz a friend Video tutorials on eye exam Iowa Eye Exam Module (from Dr. Glaucomflecken's Guide to Consulting Physical Exam Skills) Ophthalmology (35 m) IU Cases: A B C D Online MedEd: Adult Ophtho (13m) Eyes for Ears Podcast AAO Case Sudden Vision Loss Day 2: Acute Vision Loss (30m) Acute Vision Loss and Eye Guru: Dry Eye Ophthalmoscopy and Red Eye Eye Guru: Abrasions and Ulcers virtual module IU Cases: A B C D E Red Eye (30m) Corneal Transplant (2m) Eyes for Ears Podcast AAO Case Red Eye #1 AAO Case Red Eye #2 EyeGuru: Cataract EyeGuru: Glaucoma Cataract Surgery (11m) EyeGuru: AMD Glaucoma Surgery (6m) IU Cases: A B Day 3: Intravitreal Injection (4m) Eyes for Ears Podcast Independent learning Chronic Vision Loss (34m) Chronic Vision Loss AAO Case Chronic Vision Loss reflection (due Day 3 at 8 and and Systemic Disease pm) Systemic Disease (32m) EyeGuru: Diabetic Retinopathy IU Cases: A B Eyes Have It Systemic Disease Quiz AAO Case Systemic Disease #1 AAO Case Systemic Disease #2 Mid-clerkship -

Oculoplastics Product Catalog TABLE of CONTENTS

Oculoplastics Product Catalog www.fciworldwide.com TABLE OF CONTENTS FCI SAS is a world leader in the development of a wide range of ophthalmic surgical devices. EPIPHORA Since the company’s inception in 1984, the innovative PUNCTAL STENOSIS / DACRYOCYSTOPLASTY / INTUBATION SETS 5 developments of FCI have helped physicians solve problems relating to retinal detachment, epiphora, dry eye, eyelids, and orbital surgery thanks to a wide range of innovative ophthalmic devices such as lacrimal balloon DRY EYE catheter, intubation sets without nasal retrieval, punctal plugs, eyelids and orbital implants. PUNCTAL PLUGS 23 FCI performs extensive research and development to provide physicians with outstanding products that enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of surgical procedures. EYELIDS This line of product is FCI latest commitment to provide PTOSIS / EYELID WEIGHTS / EYELID PATCHES 27 you high performance products in oculoplastic surgery. ORBIT ORBITAL IMPLANTS / SELF-INFLATING TISSUE EXPANDER / ACCESSORIES 37 OCULOPLASTICS INSTRUMENTS THIS PUBLICATION IS NOT INTENDED FOR DISTRIBUTION IN THE USA. 2 OCULOPLASTICS CATALOG 2014 WWW.FCIWORLDWIDE.COM 3 EPIPHORA TABLE OF CONTENTS EPIPHORA PUNCTAL STENOSIS 6 PVP perforated plugs DACRYOCYSTOPLASTY 7 Ophtacath® INTUBATION SETS 8 Monocanalicular intubation Mini-Monoka® Monocanalicular nasolacrimal intubations 9 Masterka® Self-threading Monoka® Monoka® of Fayet Monoka® Bicanalicular intubation 12 Autostable Intubation Set II Bicanalicular nasolacrimal intubations 13 FCI Nunchaku® Ritleng® lacrimal intubation Crawford probe Infant BIKA® Infant BIKA® II BIKA® FCI 2 probe BIKA® for DCR BIKA® 1.18 LACORHINOSTOMY 18 PVP Metaireau tubes INSTRUMENTS 19 Single use Reusable 4 EPIPHORA OCULOPLASTICS CATALOG 2014 WWW.FCIWORLDWIDE.COM EPIPHORA 5 EPIPHORA POLYVINYLPYRROLIDONE (PVP) PVP is an exclusive surface treatment applied to FCI lacrimal products to improve the hydrophilic properties of silicone. -

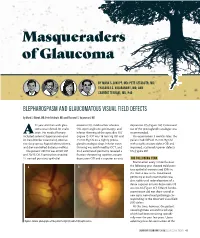

Masqueraders of Glaucoma

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS s Masqueraders of Glaucoma BY MARK S. DIKOPF, MD; PETE SETABUTR, MD; THASARAT S. VAJARANANT, MD; AND SHANDIZ TEHRANI, MD, PHD BLEPHAROSPASM AND GLAUCOMATOUS VISUAL FIELD DEFECTS By Mark S. Dikopf, MD; Pete Setabutr, MD; and Thasarat S. Vajaranant, MD 72-year-old man with glau- erosions OU, mild nuclear sclerosis depression OS (Figure 2A). Continued coma was referred for evalu- OU, open angles on gonioscopy, and use of the prostaglandin analogue was A ation. His medical history inferior thinning of the optic disc OU recommended. included systemic hypertension (not (Figure 1). IOP was 16 mm Hg OD and On examination 3 months later, the on beta-blocker treatment), obstruc- 14 mm Hg OS on a nightly prosta- patient had IOPs of 15 mm Hg OU tive sleep apnea, hypercholesterolemia, glandin analogue drop. Inferior nerve with a stable arcuate defect OD and and diet-controlled diabetes mellitus. thinning was confirmed by OCT, and improved, scattered superior defects The patient’s BCVA was 20/20 OD 24-2 automated perimetry revealed a OS (Figure 2B). and 20/25 OS. Examination revealed fixation-threatening superior arcuate 1+ corneal punctate epithelial depression OD and a superior arcuate THE FOLLOWING YEAR Examination every 3 months over A B the following year showed mild punc- tate epithelial erosions and IOPs in the mid to low teens. Automated perimetry at each examination was also stable until redevelopment of a dense superior arcuate depression OS was noted (Figure 2C). Dilated fundus examination did not show retinal or new optic nerve head pathology cor- responding to the observed visual field (VF) defect.