John Calvin's Trinitarian Theology in the 1536

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform

6 RENAISSANCE HISTORY, ART AND CULTURE Cussen Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform of Politics Cultural the and III Paul Pope Bryan Cussen Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform 1534-1549 Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform Renaissance History, Art and Culture This series investigates the Renaissance as a complex intersection of political and cultural processes that radiated across Italian territories into wider worlds of influence, not only through Western Europe, but into the Middle East, parts of Asia and the Indian subcontinent. It will be alive to the best writing of a transnational and comparative nature and will cross canonical chronological divides of the Central Middle Ages, the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period. Renaissance History, Art and Culture intends to spark new ideas and encourage debate on the meanings, extent and influence of the Renaissance within the broader European world. It encourages engagement by scholars across disciplines – history, literature, art history, musicology, and possibly the social sciences – and focuses on ideas and collective mentalities as social, political, and cultural movements that shaped a changing world from ca 1250 to 1650. Series editors Christopher Celenza, Georgetown University, USA Samuel Cohn, Jr., University of Glasgow, UK Andrea Gamberini, University of Milan, Italy Geraldine Johnson, Christ Church, Oxford, UK Isabella Lazzarini, University of Molise, Italy Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform 1534-1549 Bryan Cussen Amsterdam University Press Cover image: Titian, Pope Paul III. Museo di Capodimonte, Naples, Italy / Bridgeman Images. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 252 0 e-isbn 978 90 4855 025 8 doi 10.5117/9789463722520 nur 685 © B. -

Beauty As a Transcendental in the Thought of Joseph Ratzinger

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2015 Beauty as a transcendental in the thought of Joseph Ratzinger John Jang University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Philosophy Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Jang, J. (2015). Beauty as a transcendental in the thought of Joseph Ratzinger (Master of Philosophy (School of Philosophy and Theology)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/112 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. School of Philosophy and Theology Sydney Beauty as a Transcendental in the Thought of Joseph Ratzinger Submitted by John Jang A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy Supervised by Dr. Renée Köhler-Ryan July 2015 © John Jang 2015 Table of Contents Abstract v Declaration of Authorship vi Acknowledgements vii Introduction 1 Structure 3 Method 5 PART I - Metaphysical Beauty 7 1.1.1 The Integration of Philosophy and Theology 8 1.1.2 Ratzinger’s Response 11 1.2.1 Transcendental Participation 14 1.2.2 Transcendental Convertibility 18 1.2.3 Analogy of Being 25 PART II - Reason and Experience 28 2. -

The Well-Trained Theologian

THE WELL-TRAINED THEOLOGIAN essential texts for retrieving classical Christian theology part 1, patristic and medieval Matthew Barrett Credo 2020 Over the last several decades, evangelicalism’s lack of roots has become conspicuous. Many years ago, I experienced this firsthand as a university student and eventually as a seminary student. Books from the past were segregated to classes in church history, while classes on hermeneutics and biblical exegesis carried on as if no one had exegeted scripture prior to the Enlightenment. Sometimes systematics suffered from the same literary amnesia. When I first entered the PhD system, eager to continue my theological quest, I was given a long list of books to read just like every other student. Looking back, I now see what I could not see at the time: out of eight pages of bibliography, you could count on one hand the books that predated the modern era. I have taught at Christian colleges and seminaries on both sides of the Atlantic for a decade now and I can say, in all honesty, not much has changed. As students begin courses and prepare for seminars, as pastors are trained for the pulpit, they are not required to engage the wisdom of the ancient past firsthand or what many have labelled classical Christianity. Such chronological snobbery, as C. S. Lewis called it, is pervasive. The consequences of such a lopsided diet are now starting to unveil themselves. Recent controversy over the Trinity, for example, has manifested our ignorance of doctrines like eternal generation, a doctrine not only basic to biblical interpretation and Christian orthodoxy for almost two centuries, but a doctrine fundamental to the church’s Christian identity. -

PHIL3172: MEDIEVAL WESTERN PHILOSOPHERS 2013-2014 Venue: ELB 203 (利黃瑤璧樓 203) Time: Wednesdays 9:30 - 12:15 - Teacher: Louis Ha

PHIL3172: MEDIEVAL WESTERN PHILOSOPHERS 2013-2014 Venue: ELB 203 (利黃瑤璧樓 203) Time: Wednesdays 9:30 - 12:15 - Teacher: Louis Ha. email Middle Ages in the West lasted for more than a millennium after the downfall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th Century. During this period people lived under certain unity and uniformity commanded by the strong influence of Christianity and the common acceptance of the importance of faith in one’s daily life. This course aims at presenting the thoughts of those centuries developed in serenity and piety together with the breakthroughs made by individual philosophers such as Boethius, Anselm of Canterbury, Peter Abelard, Thomas Aquinas and Duns Scotus. Modern people, though live in a technologically advanced era, are quite often facing almost the same challenges of their Medieval fellow human-beings. The course intends to provide students with instances for a more general comprehension of human reality through the study on the problems of faith and understanding. Internal website 8 January, 2014 *INTRODUCTION The medieval Europe: the time, the place and the people The two themes and five philosophers chosen for the course Class dynamics - a) oral report by students, b) lecture by teacher, c) discussion in small groups, d) points of reflections (at least two) Assessment: attendance 10%; book report 20%(2000 words, before/on 12 Oct.); presentation 30%; term paper 40%(5000 words, before/on 23 Nov.) * The spirit of mediæval philosophy / by Étienne Gilson. * 中世紀哲學精神/ Etienne Gilson 著 ; 沈淸松譯. * [Chapters 18,19,20] 15 January, 2014 *CONSOLATIO PHILOSOPHIAE, Book V by Boethius (480-524) Boethius 22 January, 2014 *DE DIVISIONE NATURAE, Book II. -

Scotus Ord 1 D.1 Prologue

!1 This translation of the Prologue of the Ordinatio (aka Opus Oxoniense) of Blessed John Duns Scotus is complete. It is based on volume one of the critical edition of the text by the Scotus Commission in Rome and published by Frati Quaracchi. Scotus’ Latin is tight and not seldom elliptical, exploiting to the full the grammatical resources of the language to make his meaning clear (especially the backward references of his pronouns). In English this ellipsis must, for the sake of intelligibility, often be translated with a fuller repetition of words and phrases than Scotus himself gives. The possibility of mistake thus arises if the wrong word or phrase is chosen for repetition. The only check to remove error is to ensure that the resulting English makes the sense intended by Scotus. Whether this sense has always been captured in the translation that follows must be judged by the reader. So comments and notice of errors are most welcome. Peter L.P. Simpson [email protected] December, 2012 !2 THE ORDINATIO OF BLESSED JOHN DUNS SCOTUS Prologue First Part On the Necessity of Revealed Doctrine Single Question: Whether it was necessary for man in this present state that some doctrine be supernaturally inspired. Num. 1 I. Controversy between Philosophers and Theologians Num. 5 A. Opinion of the Philosophers Num. 5 B. Rejection of the Opinion of the Philosophers Num. 12 II. Solution of the Question Num. 57 III. On the Three Principal Reasons against Num. 66 the Philosophers IV. To the Arguments of the Philosophers Num. 72 V. -

John Duns Scotus's Metaphysics of Goodness

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 11-16-2015 John Duns Scotus’s Metaphysics of Goodness: Adventures in 13th-Century Metaethics Jeffrey W. Steele University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Medieval History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Scholar Commons Citation Steele, Jeffrey W., "John Duns Scotus’s Metaphysics of Goodness: Adventures in 13th-Century Metaethics" (2015). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6029 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. John Duns Scotus’s Metaphysics of Goodness: Adventures in 13 th -Century Metaethics by Jeffrey Steele A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Thomas Williams, Ph.D. Roger Ariew, Ph.D. Colin Heydt, Ph.D. Joanne Waugh, Ph.D Date of Approval: November 12, 2015 Keywords: Medieval Philosophy, Transcendentals, Being, Aquinas Copyright © 2015, Jeffrey Steele DEDICATION To the wife of my youth, who with patience and long-suffering endured much so that I might gain a little knowledge. And to God, fons de bonitatis . She encouraged me; he sustained me. Both have blessed me. “O taste and see that the LORD is good; How blessed is the man who takes refuge in Him!!” --Psalm 34:8 “You are the boundless good, communicating your rays of goodness so generously, and as the most lovable being of all, every single being in its own way returns to you as its ultimate end.” –John Duns Scotus, De Primo Principio Soli Deo Gloria . -

Christology and the 'Scotist Rupture'

Theological Research ■ volume 1 (2013) ■ p. 31–63 Aaron Riches Instituto de Filosofía Edith Stein Instituto de Teología Lumen Gentium, Granada, Spain Christology and the ‘Scotist Rupture’ Abstract This essay engages the debate concerning the so-called ‘Scotist rupture’ from the point of view of Christology. The essay investigates John Duns Scotus’s de- velopment of Christological doctrine against the strong Cyrilline tendencies of Thomas Aquinas. In particular the essay explores how Scotus’s innovative doctrine of the ‘haecceity’ of Christ’s human nature entailed a self-sufficing conception of the ‘person’, having to do less with the mystery of rationality and ‘communion’, and more to do with a quasi-voluntaristic ‘power’ over oneself. In this light, Scotus’s Christological development is read as suggestively con- tributing to make possible a proto-liberal condition in which ‘agency’ (agere) and ‘right’ (ius) are construed as determinative of what it means to be and act as a person. Keywords John Duns Scotus, ‘Scotist rupture’, Thomas Aquinas, homo assumptus Christology 32 Aaron Riches Introduction In A Secular Age, Charles Taylor links the movement towards the self- sufficing ‘exclusive humanism’ characteristic of modern secularism with a reallocation of popular piety in the thirteenth century.1 Dur- ing that period a shift occurred in which devotional practices became less focused on the cosmological glory of Christ Pantocrator and more focused on the particular humanity of the lowly Jesus. Taylor suggests that this new devotional attention to the particular human Christ was facilitated by the recently founded mendicant orders, especially the Franciscans and Dominicans, both of whom saw the meekness of God Incarnate reflected in the individual poor among whom the friars lived and ministered. -

Duns Scotus on Eternity and Timelessness

Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers Volume 14 Issue 1 Article 1 1-1-1997 Duns Scotus on Eternity and Timelessness Richard Cross Follow this and additional works at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy Recommended Citation Cross, Richard (1997) "Duns Scotus on Eternity and Timelessness," Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers: Vol. 14 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. DOI: 10.5840/faithphil19971414 Available at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy/vol14/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers by an authorized editor of ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. DUNS SCOTUS ON ETERNITY AND TIMELESSNESS Richard Cross Scotus consistently holds that eternity is to be understood as timelessness. In his early Lectura, he criticizes Aquinas' account of eternity on the grounds that (1) it entails collapsing past and future into the present, and (2) it entails a B-theory of time, according to which past, present and future are all onto logically on a par with each other. Scotus later comes to accept something like Aquinas' account of God's timelessness and the B-theory of time which it entails. Scotus also offers a refutation of his earlier argument that Aquinas' account of eternity entails collapsing past and future into the present. In this paper, I want to establish two conclusions. The main one will be that Scotus has a conception of eternity as timelessness. -

Duns Scotus' Life and Works – Ideas of Theology

Duns Scotus’ Life and Works – Ideas of Theology 1 Chapter 1 Duns Scotus’ Life and Works – Ideas of Theology 1.1 Introduction John Duns Scotus’ life seems to have been rather simple and uneventful. In fact, despite being brief, it was full of tensions and drama. Likewise, Scotism seems to have had an inconspicuous standing within the development of Western thought, but if we were to interview important Christian intellectual leaders at the beginning of the fourteenth century, we would discover that his thought was seen as the summit of mainstream thirteenth-century thought. It is also a tradition constitutive throughout the vicissitudes of the history of Western thoug ht until the end of the eighteenth century. Even as late as the seventeenth century, Scotus’ influence was remarkably powerful.1 However, the picture of nineteenth-century thought is quite a different one, for nine- teenth- and twentieth-century theology and philosophy created alternative ways of thinking than before 1800, which were diametrically opposed to Scotism in logic, ontology, ethics and the doctrine of God. After 1800, the classic tradition of Christian scholastic thought collapsed. What had been essential became marginal. Duns Scotus’ enormous influence for five centuries is all the more remarkable because of his short life. He died sudddenly in Cologne (Germany) on 8 November 1308, at only 42 years of age. This chapter presents an overview of Duns’ life and works. First, I tell about the back ground of his life and work (§ 1.2). Of all the great philosophers, John Duns Scotus is the one whose life is least known and whose biography rests almost entirely on conjecture.2 But now the true story can be told. -

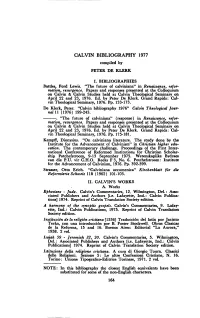

1977 Compiled by PETER DE KLERK

CALVIN BIBLIOGRAPHY 1977 compiled by PETER DE KLERK I. BIBLIOGRAPHIES Battles, Ford Lewis. "The future of calviniana" in Renaissance, refor mation, resurgence. Papers and responses presented at the Colloquium on Calvin & Calvin Studies held at Calvin Theological Seminary on April 22 and 23, 1976. Ed. by Peter De Klerk. Grand Rapids: Cal vin Theological Seminary, 1976. Pp. 133-173. De Klerk, Peter. "Calvin bibliography 1976" Calvin Theological Jour- nal U (1976) 199-243. -. "The future of calviniana" (response) in Renaissance, refor mation, resurgence. Papers and responses presented at the Colloquium on Calvin & Calvin Studies held at Calvin Theological Seminary on April 22 and 23, 1976. Ed. by Peter De Klerk. Grand Rapids: Cal vin Theological Seminary, 1976. Pp. 175-181. Kempff, Dionysius. "On calviniana literature. The study done by the Institute for the Advancement of Calvinism" in Christian higher edu cation. The contemporary challenge. Proceedings of the First Inter national Conference of Reformed Institutions for Christian Scholar ship Potchefstroom, 9-13 September 1975. Wetenskaplike Bydraes van die P.U. vir C.H.O. Reeks F 3, No. 6. Potchefstroom: Institute for the Advancement of Calvinism, 1976. Pp. 392-399. Strasser, Otto Erich. "Calviniana œcumenica" Kirchenblatt für die Reformierte Schweiz 118 (1962) 101-103. II. CALVIN'S WORKS A. Works Ephesians - Jude. Calvin's Commentaries, 12. Wilmington, Del.: Asso ciated Publishers and Authors [i.e. Lafayette, Ind.: Calvin Publica tions] 1974. Reprint of Calvin Translation Society edition. A harmony of the synoptic gospels. Calvin's Commentaries, 9. Lafay ette, Ind.: Calvin Publications, 1975. Reprint of Calvin Translation Society edition. Institución de la religion cristiana fi536] Traducción del latín por Jacinto Terán, con una introducción por Β. -

Intentions and Conscious Moral Choices in Peter Abelard's Know

Intentions and Conscious Moral Choices in Peter Abelard’s Know Yourself Taina M. Holopainen Introduction Peter Abelard was a remarkable twelfth-century promoter of ethical thought. Two of his works are dedicated to ethics. The earlier one is the Dialogue between a Philosopher, a Jew, and a Christian, also known as the Collationes, and com- posed some time between 1123 and 1135. The work consists of an imaginary dia- logue, one in which none of the characters directly represents Abelard’s own position but through which it becomes clear that Abelard had a high apprecia- tion of philosophical ethics.1 The later of Abelard’s works on ethics is the trea- tise Scito te ipsum or Know Yourself, also called the Ethica or Ethics.2 The book is undoubtedly one of the most important early medieval works in theological or philosophical ethics. In the following article my discussion on Abelard’s idea of moral action will be based on this work. Abelard wrote his Ethics around the year 1138, only a few years before his death in 1142. The treatise was meant to consist of two books, of which the first was to discuss morally bad acts, or sin, and the second morally good acts. Only the first book has come down to us in full; we have just the very beginning of the second. Therefore the examples available mainly deal with morally bad acts. My topic, however, focuses on the role of intention in morally relevant action and therefore takes into account both morally good and morally bad acts.3 1 Coll., ed. -

The Moral Significance of Creation in the Franciscan Theological Tradition: Implications for Contemporary Catholics and Public Policy

\\server05\productn\U\UST\5-1\UST104.txt unknown Seq: 1 10-JUN-08 8:35 ESSAY THE MORAL SIGNIFICANCE OF CREATION IN THE FRANCISCAN THEOLOGICAL TRADITION: IMPLICATIONS FOR CONTEMPORARY CATHOLICS AND PUBLIC POLICY KEITH DOUGLASS WARNER, O.F.M.* I. St. Francis, the Patron Saint of Those Who Promote Ecology ................................................. 40 R II. St. Bonaventure and Creation’s Theological Significance . 42 R III. John Duns Scotus: Creation Was Created for Christ ........ 46 R IV. Conclusion: Implications for Contemporary Catholics and Public Policy ............................................ 47 R Pope John Paul II launched Catholic concern for the environment with his 1990 World Day of Peace Message, The Ecological Crisis: A Common Responsibility.1 He articulated new ethical duties for Catholics, indeed for the whole human family, and in this article, I interpret these duties in light of the eight-hundred-year-old Franciscan theological tradition. Pope John Paul II described the environmental crisis as rooted in a moral crisis for humanity, caused by our selfishness, our sin, and our lack of respect for life.2 He proposed several ethical remedies. He said humanity should explore, examine and “safeguard” (alternative translation: steward) the integrity of creation.3 He described duties of human individuals and institutions of all kinds: the nations of the world should cooperate in the * Santa Clara University. This essay was presented at the University of St. Thomas School of Law Symposium Peace with Creation: Catholic Perspectives on Environmental Law. Ilia De- lio, O.S.F., Kenan Osborne, O.F.M., Bill Short, O.F.M., and Joseph Chinnici, O.F.M., contributed wisdom and insights on earlier versions of these ideas.