From Seamount to Oceanic Island, Porto Santo, Central East-Atlantic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flood Basalts and Glacier Floods—Roadside Geology

u 0 by Robert J. Carson and Kevin R. Pogue WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Information Circular 90 January 1996 WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENTOF Natural Resources Jennifer M. Belcher - Commissioner of Public Lands Kaleen Cottingham - Supervisor FLOOD BASALTS AND GLACIER FLOODS: Roadside Geology of Parts of Walla Walla, Franklin, and Columbia Counties, Washington by Robert J. Carson and Kevin R. Pogue WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Information Circular 90 January 1996 Kaleen Cottingham - Supervisor Division of Geology and Earth Resources WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Jennifer M. Belcher-Commissio11er of Public Lands Kaleeo Cottingham-Supervisor DMSION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Raymond Lasmanis-State Geologist J. Eric Schuster-Assistant State Geologist William S. Lingley, Jr.-Assistant State Geologist This report is available from: Publications Washington Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources P.O. Box 47007 Olympia, WA 98504-7007 Price $ 3.24 Tax (WA residents only) ~ Total $ 3.50 Mail orders must be prepaid: please add $1.00 to each order for postage and handling. Make checks payable to the Department of Natural Resources. Front Cover: Palouse Falls (56 m high) in the canyon of the Palouse River. Printed oo recycled paper Printed io the United States of America Contents 1 General geology of southeastern Washington 1 Magnetic polarity 2 Geologic time 2 Columbia River Basalt Group 2 Tectonic features 5 Quaternary sedimentation 6 Road log 7 Further reading 7 Acknowledgments 8 Part 1 - Walla Walla to Palouse Falls (69.0 miles) 21 Part 2 - Palouse Falls to Lower Monumental Dam (27.0 miles) 26 Part 3 - Lower Monumental Dam to Ice Harbor Dam (38.7 miles) 33 Part 4 - Ice Harbor Dam to Wallula Gap (26.7 mi les) 38 Part 5 - Wallula Gap to Walla Walla (42.0 miles) 44 References cited ILLUSTRATIONS I Figure 1. -

Geochemistry of Sideromelane and Felsic Glass Shards in Pleistocene Ash Layers at Sites 953, 954, and 9561

Weaver, P.P.E., Schmincke, H.-U., Firth, J.V., and Duffield, W. (Eds.), 1998 Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, Vol. 157 25. GEOCHEMISTRY OF SIDEROMELANE AND FELSIC GLASS SHARDS IN PLEISTOCENE ASH LAYERS AT SITES 953, 954, AND 9561 Andrey A. Gurenko2 and Hans-Ulrich Schmincke2 ABSTRACT Sideromelane and felsic glass shards from unconsolidated Pleistocene volcaniclastic sediments drilled at Sites 953, 954, and 956 are thought to have derived from submarine and subaerial volcanic eruptions on Gran Canaria (Sites 953 and 954) and Tenerife (Sites 954 and 956). We analyzed these glasses by electron microprobe for major elements and sulfur, chlorine, and fluorine. Sideromelane glasses represent a spectrum from alkali basalt through basanite, hawaiite, mugearite, and tephrite to nephelinite. Felsic glasses have compositions similar to benmoreite, trachyte, and phonolite. Vesiculated mafic and felsic glass shards, which are characterized by low S and Cl concentrations (0.01−0.06 wt% S and 0.01–0.04 wt% Cl), are interpreted to have formed by pyroclastic activity on land or in shallow water and appeared to have been strongly degassed. Vesicle-free blocky glass shards having 0.05−0.13 wt% S are likely to have resulted from submarine eruptions at moderate water depths and represent undegassed or slightly degassed magmas. Cl concentrations range from 0.01 to 0.33 wt% and increase with increasing MgO, suggesting that Cl behaves as an incompatible element during magma crystallization. Concentrations of fluorine (0.04− 0.34 wt% F) are likely to represent undegassed values, and the variations in F/K ratios between 0.02 and 0.24 are believed to reflect those of parental magmas and of the mantle source. -

The Hyaloclastite Ridge Formed in the Subglacial 1996 Eruption in Gjfilp, Vatnaj6kull, Iceland: Present Day Shape and Future Preservation

The hyaloclastite ridge formed in the subglacial 1996 eruption in Gjfilp, Vatnaj6kull, Iceland: present day shape and future preservation M. T. GUDMUNDSSON, F. PALSSON, H. BJORNSSON & ~. HOGNADOTTIR Science Institute, University of Iceland, Hofsvallag6tu 53, 107 Reykjavik, Iceland (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract: In the Gjfilp eruption in 1996, a subglacial hyaloclastite ridge was formed over a volcanic fissure beneath the Vatnaj6kull ice cap in Iceland. The initial ice thickness along the 6 km-long fissure varied from 550 m to 750 m greatest in the northern part but least in the central part where a subaerial crater was active during the eruption. The shape of the subglacial ridge has been mapped, using direct observations of the top of the edifice in 1997, radio echo soundings and gravity surveying. The subglacial edifice is remarkably varied in shape and height. The southern part is low and narrow whereas the central part is the highest, rising 450 m above the pre-eruption bedrock. In the northern part the ridge is only 150-200m high but up to 2kin wide, suggesting that lateral spreading of the erupted material occurred during the latter stages of the eruption. The total volume of erupted material in Gj~tlp was about 0.8 km 3, mainly volcanic glass. The edifice has a volume of about 0.7 km 3 and a volume of 0.07 km 3 was transported with the meltwater from Gj~lp and accumulated in the Grimsv6tn caldera, where the subglacial lake acted as a trap for the sediments. This meltwater-transported material was removed from the southern part of the edifice during the eruption. -

Nonexplosive and Explosive Magma/Wet-Sediment Interaction

Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 181 (2009) 155–172 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jvolgeores Nonexplosive and explosive magma/wet-sediment interaction during emplacement of Eocene intrusions into Cretaceous to Eocene strata, Trans-Pecos igneous province, West Texas Kenneth S. Befus a,⁎, Richard E. Hanson a, Daniel P. Miggins b, John A. Breyer a, Arthur B. Busbey a a Department of Geology, Texas Christian University, Box 298830, Fort Worth, TX 76129, USA b U.S. Geological Survey, Denver Federal Center, Box 25046, Denver, CO 80225, USA article info abstract Article history: Eocene intrusion of alkaline basaltic to trachyandesitic magmas into unlithified, Upper Cretaceous Received 16 June 2008 (Maastrichtian) to Eocene fluvial strata in part of the Trans-Pecos igneous province in West Texas produced Accepted 22 December 2008 an array of features recording both nonexplosive and explosive magma/wet-sediment interaction. Intrusive Available online 13 January 2009 complexes with 40Ar/39Ar dates of ~47–46 Ma consist of coherent basalt, peperite, and disrupted sediment. Two of the complexes cutting Cretaceous strata contain masses of conglomerate derived from Eocene fluvial Keywords: deposits that, at the onset of intrusive activity, would have been N400–500 m above the present level of phreatomagmatism peperite exposure. These intrusive complexes are inferred to be remnants of diatremes that fed maar volcanoes during diatreme an early stage of magmatism in this part of the Trans-Pecos province. Disrupted Cretaceous strata along Trans-Pecos Texas diatreme margins record collapse of conduit walls during and after subsurface phreatomagmatic explosions. -

The Pitcairn Hotspot in the South Paci¢C: Distribution and Composition of Submarine Volcanic Sequences

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com R Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 121 (2003) 219^245 www.elsevier.com/locate/jvolgeores The Pitcairn hotspot in the South Paci¢c: distribution and composition of submarine volcanic sequences R. Hekinian a;Ã, J.L. Chemine¤e b, J. Dubois b, P. Sto¡ers a, S. Scott c, C. Guivel d, D. Garbe-Scho«nberg a, C. Devey e, B. Bourdon b, K. Lackschewitz e, G. McMurtry f , E. Le Drezen g a Universita«t Kiel, Institut fu«r Geowissenschaften, OlshausentraMe 40, 24098 Kiel, Germany b Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, 4 Place Jussieu, 75252 Paris, France c Geology Department, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada M5S 3B1 d Universite¤ de Nantes, Faculte¤ des Sciences, 2 Rue de la Houssinie're, 92208 Nantes, France e University of Bremen, Geowissenschaften, Postfach 340440, 28334 Bremen, Germany f University of Hawaii, Department of Oceanography, 1000 Pope Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA g IFREMER Centre de Brest, Ge¤oscience Marine, 29280 Plouzane¤, France Received 19 March 2002; accepted 30 August 2002 Abstract Multibeam bathymetry and bottom imaging (Simrad EM12D) studies on an area of about 9500 km2 were conducted over the Pitcairn hotspot near 25‡10PS, 129‡ 20PW. In addition, 15 dives with the Nautile submersible enabled us to obtain ground-true observations and to sample volcanic structures on the ancient ocean crust of the Farallon Plate at 3500^4300 m depths. More than 100 submarine volcanoes overprint the ancient crust and are divided according to their size into large ( s 2000 m in height), intermediate (500^2000 m high) and small ( 6 500 m high) edifices. -

Analogues for Radioactive Waste For~1S •

PNL-2776 UC-70 3 3679 00049 3611 ,. NATURALLY OCCURRING GLASSES: ANALOGUES FOR RADIOACTIVE WASTE FOR~1S • Rodney C. Ewing Richard F. Haaker Department of Geology University of New Mexico Albuquerque, ~ew Mexico 87131 April 1979 Prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract EY-76-C-06-1830 Pacifi c i'lorthwest Laboratory Richland, Washington 99352 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables. i i List of Figures iii Acknowledgements. Introduction. 3 Natural Glasses 5 Volcanic Glasses 9 Physical Properties 10 Compos i ti on . 10 Age Distributions 10 Alteration. 27 Devitrification 29 Hydration 32 Tekti tes. 37 Physical Properties 38 Composition . 38 Age Distributions . 38 Alteration, Hydration 44 and Devitrification Lunar Glasses 44 Summary . 49 Applications to Radioactive Waste Disposal. 51 Recommenda ti ons 59 References 61 Glossary 65 i LIST OF TABLES 1. Petrographic Properties of Natural Glasses 6 2. Average Densities of Natural Glasses 11 3. Density of Crystalline Rock and Corresponding Glass 11 4. Glass and Glassy Rocks: Compressibility 12 5. Glass and Glassy Rocks: Elastic Constants 13 6. Glass: Effect of Temperature on Elastic Constants 13 7. Strength of Hollow Cylinders of Glass Under External 14 Hydrostatic Pressure 8. Shearing Strength Under High Confining Pressure 14 9. Conductivity of Glass 15 10. Viscosity of Miscellaneous Glasses 16 11. Typical Compositions for Volcanic Glasses 18 12. Selected Physical Properties of Tektites 39 13. Elastic Constants 40 14. Average Composition of Tektites 41 15. K-Ar and Fission-Track Ages of Tektite Strewn Fields 42 16. Microprobe Analyses of Various Apollo 11 Glasses 46 17. -

Icelandic Hyaloclastite Tuffs Petrophysical Properties, Alteration and Geochemical Mobility

Icelandic Hyaloclastite Tuffs Petrophysical Properties, Alteration and Geochemical Mobility Hjalti Franzson Gudmundur H. Gudfinnsson Julia Frolova Helga M. Helgadóttir Bruce Pauly Anette K. Mortensen Sveinn P. Jakobsson Prepared for National Energy Authority and Reykjavík Energy ÍSOR-2011/064 ICELAND GEOSURVEY Reykjavík: Orkugardur, Grensásvegur 9, 108 Reykjavík, Iceland - Tel.: 528 1500 - Fax: 528 1699 Akureyri: Rangárvellir, P.O. Box 30, 602 Akureyri, Iceland - Tel.: 528 1500 - Fax: 528 1599 [email protected] - www.isor.is Report Project no.: 540105 Icelandic Hyaloclastite Tuffs Petrophysical Properties, Alteration and Geochemical Mobility Hjalti Franzson Gudmundur H. Gudfinnsson Julia Frolova Helga M. Helgadóttir Bruce Pauly Anette K. Mortensen Sveinn P. Jakobsson Prepared for National Energy Authority and Reykjavík Energy ÍSOR-2011/064 December 2011 Key page Report no. Date Distribution ÍSOR-2011/064 December 2011 Open Closed Report name / Main and subheadings Number of copies Icelandic Hyaloclastite Tuffs. Petrophysical Properties, Alteration 7 and Geochemical Mobility Number of pages 103 Authors Project manager Hjalti Franzson, Gudmundur H. Gudfinnsson, Julia Frolova, Hjalti Franzson Helga M. Helgadóttir, Bruce Pauly, Anette K. Mortensen and Sveinn P. Jakobsson Classification of report Project no. 540105 Prepared for National Energy Authority and Reykjavík Energy Cooperators Moscow University, University of California in Davis, Natural History Museum in Iceland Abstract This study attempts to define the properties of hyaloclastite formations which control their petrophysical characteristics during their progressive alteration. It is based on 140 tuffaceous cores from last glaciation to 2–3 m y. The water content shows a progressive increase with alteration to about 12%, which mainly is bound in the smectite and zeolite alteration minerals. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 07 June 2010 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Jerram, Dougal A. and Single, Richard T. and Hobbs, Richard W. and Nelson, Catherine E (2009) 'Understanding the oshore ood basalt sequence using onshore volcanic facies analogues : an example from the Faroe-Shetland basin.', Geological magazine., 146 (3). pp. 353-367. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0016756809005974 Publisher's copyright statement: c Copyright Cambridge University Press 2009. This paper has been published by Cambridge University Press in "Geological magazine"(146: 3 (2009) 353-367) http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayJournal?jid=GEO Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Geol. Mag. 146 (3), 2009, pp. 353–367. c 2009 Cambridge University Press 353 doi:10.1017/S0016756809005974 Printed in the United Kingdom Understanding the offshore flood basalt sequence using onshore volcanic facies analogues: an example from the Faroe–Shetland basin ∗ ∗ ∗ DOUGAL A. -

Subglacial and Submarine Volcanism in Iceland

Mars Polar Science 2000 4078.pdf SUBGLACIAL AND SUBMARINE VOLCANISM IN ICELAND. S. P. Jakobsson, Icelandic Inst. of Natural His- tory, P. O. Box 5320, 125 Reykjavik, Iceland Introduction: Iceland is the largest landmass ex- mounds, ridges and tuyas [5]. The thickness of basal posed along the Mid-Ocean Ridge System. It has been basaltic pillow lava piles often exceeds 60-80 meters constructed over the past 16 Ma by basaltic to silicic and a 300 m thick section has been reported. Pillow volcanic activity occurring at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, lavas may also form lenses or pods at a higher level in and is topographically elevated because of the abundant the volcanoes. igneous material produced in association with the Ice- It has been suggested that at a water depth less than land hot spot, the center of which is thought to be lo- approximately 100-150 m, basaltic phreatic explosions cated beneath Vatnajokull glacier [1]. The axial rift produce hydroclastites. It appears feasible to subdivide zones which run through Iceland from southwest to the hyaloclastites of the Icelandic ridges and tuyas, ge- northeast are in direct continuation of the crestal zones netically into two main types. A substantial part of the of the Mid Atlantic Ridge and are among the most ac- base of the submarine Surtsey tuya is poorly bedded, tive volcanic zones on Earth. unsorted, hydroclastite, which probably was quenched Subglacial Volcanism: Volcanic accumulations of and rapidly accumulated below the seawater level with- hyaloclastites which are deposits formed by the intru- out penetrating the surface [6]. Only 1-2 % of the vol- sion of lava beneath water or ice and the consequent ume of extruded material in the 1996 Gjalp eruption fell shattering into small angular vitric particles, combined as air-fall tephra, the bulk piled up below the ice [4]. -

29. Sulfur Isotope Ratios of Leg 126 Igneous Rocks1

Taylor, B., Fujioka, K., et al., 1992 Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, Vol. 126 29. SULFUR ISOTOPE RATIOS OF LEG 126 IGNEOUS ROCKS1 Peter Torssander2 ABSTRACT Sulfur isotope ratios have been determined in 19 selected igneous rocks from Leg 126. The δ34S of the analyzed rocks ranges from -0.1 o/00 to +19.60 o/oo. The overall variation in sulfur isotope composition of the rocks is caused by varying degrees of seawater alteration. Most of the samples are altered by seawater and only five of them are considered to have maintained their magmatic sulfur isotope composition. These samples are all from the backarc sites and have δ34S values varying from +0.2 o/oo to +1.6 o/oo , of which the high δ34S values suggest that the earliest magmas in the rift are more arc-like in their sulfur isotope composition than the later magmas. The δ34S values from the forearc sites are similar to or heavier than the sulfur isotope composition of the present arc. INTRODUCTION from 0 o/oo to +9 o/00 (Ueda and Sakai, 1984), which could arise from inhomogeneities in the mantle but are more likely a result of contami- Sulfur is a volatile element that can be degassed during the ascent nation from the subducting slab (A. Ueda, pers. comm., 1988). of basaltic magma. Degassing causes sulfur isotope fractionation; the Leg 126 of the Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) drilled seven sites isotopic composition of sulfur in rocks can vary with the concentra- in the backarc and forearc of the Izu-Bonin Arc (Fig. -

Historic Littoral Cones in Hawaii

Historic Littoral Cones in Hawaii JAMES G. MOORE AND WAYNE U. AULT 1 ABSTRACT: Littoral cones are formed by steam explosions resulting when lava flows enter the sea. Of about 50 littOral cones on the shores of Mauna Loa and Kilauea on the island of Hawaii, three were formed in historic time: 1840, 1868, and 1919. Five new chemical analyses of the glassy ash of the cones and of the feeding lava show that there is no chemical interchange between molten lava and sea water during the brief period they are in contact. The littoral cone ash contains a lower Fe20g / (Fe20g + FeO) ratio than does its feeding lava because drastic chilling reduces the amount of oxidation. A large volume of lava entering the sea (probably more than 50 million cubic yards) is required to produce a littoral cone. All the histOric littOral cones were fed by aa flows. The turbulent character of these flows and the included cooler, solid material allows ingress of sea water to the interior of the flow where it vaporizes and explodes. The cooler, more brittle lava of the aa flows tend to fragment and shatter more readily upon contact with water than does lava of pahoehoe flows. LITfORAL CONES are common features on the three volcanoes (Mauna Kea, Kohala, and Hua shores of the younger volcanoes of Hawaii lalai) of which the island is composed, nor have (Wentworth and Macdonald, 1953:28). These any littOral cones been mapped on any of the cinder cones do not mark the site of a primary other Hawaiian Islands. -

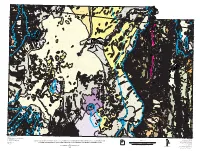

Geologic Map of Delta 30' X 60' Quadrangle

113 00' 33 R 10 W 3 -Cpm 4 R 9 W p-Cm - R 8 W 45' 35 Qla P Cp Qla Qvb 3 B Qla QTlf Qlm 5 6 R 7 W Qla Qaf1 3 R 5 W 3 Qpm Qed R 6 W 7 30' 8 3 A Qaf1 -Cp Qla Qaf1 Qes Qlm Qlf Qpm R 4 W 9 15' Qlg Qed Qed Qlf Qla Qaf1 Qed Qed Qla Qpm Qed Qed P Qlm QTlf Qlm Qed p-Cc Qaf2 Qaf Qlf Qed Qdf Tdr Qaf1 1 Qed Qed -Cpm p-Cm Qla Qla Qla Qlf Qed Qed p-Cm Tdi Qaf1 Qla Qed Qed p-Cc B Qdf Trk Qaf2 Qlm Qaf1 Qed 85 86 -Cdh -Cp Qed Qaf1 Qaf1 30 Qaf Qlf Qed Qed -Cp Tdr 1 Qed B Qla Qpm Qdf B -Cpm -Cpm P Qlf Qed Qal -Cdh -Cp Qlm Qla 1 p-Cm -Cp Qaf1 Qed Qlf Qal - Qed 2 -Cpm Cdh ? Qdf Qdf Qdg p-Cc -Cdh Qla Qla Qlf/Qal /QTlf Qdg/Qdf Qal2 60 -Cum -Cp 25 3 Qed p-Ci 45 -Cww - Qla Qed Qed Qed Qdf -Cp Cpm -Cpm Qed Qdg Kc Qla Qpm Qed -Cpm 87 -Cdh -Cdh Qaf1 Qed Qdg -Cdh -Cp Qpm -Cww Qla Qdg Qes Qdf B -Cp Qed Qed Qed Qdf Qaf1 - P Cp B Qdg 20 -Cww Qla Qpm Qes p-Cm -Cp -Cww 30 Qaf -Cum Qaf 1 2 -Cp Qla Qed Qal2 -Cdh -Cdh -Cdh Qed Qes p-Cm Qed Qed Qaf1 -Cpm -Cmp Qla P Qed Qal1 -Cww Qms Qla 78-1 -Cp Kc -Cdh Qed Qed Qdf - p-Cm -Cww 86 39 30' Qaf2 -Cmp Cmp -Cww -Cum 80 B Qaf1 Qlm Qed Tdr Qed 64 Tdr Qaf Qlg Qdf Qdf Qdf 60 2 Qal2 Qaf1 Qlg Qed p-Cm Qaf2 Qla P Qal Tdr Qlg Qaf Qla 1 R 3 W 40 Qla 1 Qes Qed 1 825 R 2 W 41 1 850 000 FEET 112 00' T 15 S -Cww QTaf QTas Qdf 39 30' Qlm Qed Qaf -Cdh QTaf Qdf 1 -Cum Qaf1 Qdf 15 Tf Qaf2 Qaf Qaf1 ? QTaf Qac 2 Qaf -Cp QTaf Qlg Tdr 2 Qal p-Cc Qms Qaf1 B Tbsk 1 85 QTaf QTaf Qdf Tf B Qlg Qdf TKn Qaf Qdf Qal Qes Qal2 Qla p-Cc Qaf2 Qms 1 Tf Qaf Tdr Qla Qla 2 Qes Qed QTas 2 Qaf1 -Cdh QTaf Qaf Qed p-Cm - Tf Qlg Qaf2 1 Tbsk -Cp Cww QTaf - 40 TKn QTaf QTaf