ED 034 980 INSTITUTION PUB DATE EDFS PRICE DESCRIPTORS TDENTIFIEPS DOCUMENT RESUME Pegional Seminar on New Developments in the T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

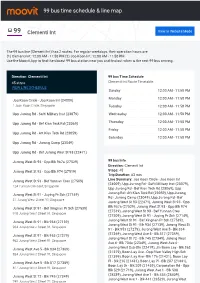

99 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

99 bus time schedule & line map 99 Clementi Int View In Website Mode The 99 bus line (Clementi Int) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Clementi Int: 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM (2) Joo Koon Int: 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 99 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 99 bus arriving. Direction: Clementi Int 99 bus Time Schedule 45 stops Clementi Int Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Joo Koon Circle - Joo Koon Int (24009) 1 Joon Koon Circle, Singapore Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Safti Military Inst (23079) Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Bef Kian Teck Rd (23069) Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Friday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Aft Kian Teck Rd (23059) Saturday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Jurong Camp (23049) Upp Jurong Rd - Bef Jurong West St 93 (22471) Jurong West St 93 - Opp Blk 987a (27529) 99 bus Info Direction: Clementi Int Jurong West St 93 - Opp Blk 974 (27519) Stops: 45 Trip Duration: 63 min Jurong West St 93 - Bef Yunnan Cres (27509) Line Summary: Joo Koon Circle - Joo Koon Int (24009), Upp Jurong Rd - Safti Military Inst (23079), 124 Yunnan Crescent, Singapore Upp Jurong Rd - Bef Kian Teck Rd (23069), Upp Jurong Rd - Aft Kian Teck Rd (23059), Upp Jurong Jurong West St 91 - Juying Pr Sch (27149) Rd - Jurong Camp (23049), Upp Jurong Rd - Bef 31 Jurong West Street 91, Singapore Jurong West St 93 (22471), Jurong West St 93 - Opp Blk 987a (27529), Jurong West St 93 - Opp Blk -

Ministry of Health List of Approved Providers for Antigen Rapid Testing for COVID-19 at Offsite Premises List Updated As at 21 May 2021

Ministry of Health List of Approved Providers for Antigen Rapid Testing for COVID-19 at Offsite Premises List updated as at 21 May 2021. Contact Service Provider Site of Event Testing Address of Site Date of Event No. OCBC Square 1 Stadium Place #01-K1/K2, Wave Mall, - Singapore 397628 57 Medical Clinic (Geylang Visitor Centre of Singapore Sports Hub 8 Stadium Walk, Singapore 397699 - 66947078 Bahru) Suntec Singapore Convention and Exhibition 1 Raffles Boulevard Singapore 039593 - Centre 9 Dec 2020 13 and 14 Jan 2021 24 and 25 Jan 2021 Sands Expo and Convention Centre 10 Bayfront Avenue, Singapore 018956 4 Feb 2021 24 and 25 Mar 2021 19 Apr 2021 PUB Office 40 Scotts Road, #22-01 Environment - Ally Health Building, Singapore 228231 (in partnership with Jaga- 67173737 The Istana 35 Orchard Road, Singapore 238823 3 and 4 Feb 2021 Me) 11 Feb 2021 One Marina Boulevard 1 Marina Boulevard, Singapore 018989 11 Feb 2021 Rasa Sentosa Singapore 101 Siloso Road, Singapore 098970 CSC@Tessensohn 60 Tessensohn Road, Singapore 217664 10 Apr 2021 Shangri-La Hotel Singapore 22 Orange Grove Road, Singapore 258350 22 Apr 2021 D'Marquee@Downtown East 1 Pasir Ris Close, Singapore 519599 - Intercontinental Hotel 80 Middle Road, Singapore 188966 - Bethesda Medical Centre MWOC @ Ponggol Northshore 501A Ponggol Way, Singapore 828646 - MWOC @ CCK 10A Lorong Bistari, Singapore 688186 - 63378933 MWOC @ Eunos 10A Eunos Road 1, Singapore 408523 - MWOC @ Tengah A 1A Tengah Road, Singapore 698813 - MWOC @ Tengah B 3A Tengah Road, Singapore 698814 - Page 1 of 112 Hotel -

Submerged Outlet Drain Once in Three Month Desilting and Flushing

Submerged Outlet Drain Once in Three Month Desilting and Flushing Drain S/No Location Frequency Length 4.5m wide U-drain from the culvert at Jurong Road near Track 22 to the 1 outlet of the culvert at PIE (including the culverts across Jurong Road and 65 1st week of the month across PIE) 9m/12m wide Sungei Jurong subsidiary drain running along PIE from L/P 2 380 1st week of the month 606 to L/P 586 1.5m wide U-drain/covered drain from the junction of Yuan Ching Road/ 3 790 2nd week of the month Jalan Ahmad 13m wide U-drain from Jurong West Street 65 to Major Drain MJ 14 near 4 450 2nd week of the month Blk 664A 15m wide Sg Jurong subsidiary drain from L/P 586 at PIE to Sg Jurong 5 950 2nd week of the month including one 6 10m wide Sg Jurong subsidiary drain from L/P 534 at PIE to Sg Jurong 1180 3rd week of the month Along Boon Lay Way opposite Jurong West Street 61 to Jalan Boon Lay 7 1300 4th week of the month and at Enterprise Road 8 Blk 664A Jurong West Street 64 to MJ13 650 4th week of the month 9 Sungei Lanchar (From Jalan Boon Lay to Jurong Lake 1,600 5th week of the month 10 Sungei Jurong (From Ayer Rajah Expressway to Jurong Lake) 1070 6th week of the month 3.0m wide Outlet drain from culvert at Teban Garden Road running along 11 Jurong Town Hall Road and West Coast Road to Sg Pandan opposite Block 650 7th week of the month 408 30.0m wide Sg Pandan from the branch connection to the downstream Boon 12 350 7th week of the month Lay Way to Sg Ulu Pandan 13 Sungei Pandan (from confluence of Sg Pandan to West Coast Road) 600 7th week -

Download Program

5th IEA International Research Conference 26–28 June 2013 Workshops 24–25 June 2013 Singapore International Association NTU Full Logo printing on uncoated stock: CMYK for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement 0C 100M 90Y 0K 100C 68M 7Y 28K Program IRC-2013 AGENDA WORKSHOPS 24–25 June 2013 | 9:00–17:00 (coffee breaks at 10:15–10:45 and 14:45–15:15; lunch break at 12:00–13:30) Workshop 1 Workshop 2 Workshop 3 Workshop 4 Introduction to IEA Databases Using HLM With International Assessment Designs, Item Sampling in Large-Scale and IDB Analyzer Large-Scale Assessment Data Response Theory, and Assessments in Education Room NIE7-01-TR708 Room NIE7-01-TR709 Proficiency Estimates Room NIE7-01-TR712 Room NIE7-01-TR710 RECEPTION 25 June 2013 | 19:00 | Location Pan Pacific Singapore CONFERENCE 26–28 June 2013 Wednesday, 26 June 2013 Thursday, 27 June 2013 Friday, 28 June 2013 Registration Registration Registration 8:00–16:00 | Foyer of NIE6-01-LT1 8:30–16:00 | Foyer of NIE6-01-LT1 8:30–12:00 | Foyer of NIE6-01-LT1 Opening Ceremony Keynote 3 Keynote 4 9:00–9:30 | NIE6-01-LT1 Inequality and Academic Achievement Quality of Schools and Teaching: What Can 9:00–10:00 | NIE6-01-LT1 We Learn From International Studies? Keynote 1 Larry V. Hedges, Northwestern University, 9:00–10:00 | NIE6-01-LT1 Mathematics Education in Singapore United States Eckhard Klieme, German Institute for | NIE6-01-LT1 9:30–10:30 International Educational Research Berinderjeet Kaur, National Institute of Education, Singapore Coffee Break Coffee Break 10:00–10:30 | Foyer of NIE6-01-LT1 -

JURONG Heritage Trail

T he Jurong Heritage Trail is part of the National Heritage Board’s ongoing efforts » DISCOVER OUR SHARED HERITAGE to document and present the history and social memories of places in Singapore. We hope this trail will bring back fond memories for those who have worked, lived or played in the area, and serve as a useful source of information for new residents JURONG and visitors. HERITAGE TRAIL » CONTENTS » AREA MAP OF Early History of Jurong p. 2 Historical extent of Jurong Jurong The Orang Laut and early trade routes Early accounts of Jurong The gambier pioneers: opening up the interior HERITAGE TRAIL Evolution of land use in Jurong Growth of Communities p. 18 MARKED HERITAGE SITES Villages and social life Navigating Jurong Beginnings of industry: brickworks and dragon kilns 1. “60 sTalls” (六十档) AT YUNG SHENG ROAD ANd “MARKET I” Early educational institutions: village schools, new town schools and Nanyang University 2. AROUND THE JURONG RIVER Tide of Change: World War II p. 30 101 Special Training School 3. FORMER JURONG DRIVE-IN CINEMA Kranji-Jurong Defence Line Backbone of the Nation: Jurong in the Singapore Story p. 35 4. SCIENCE CENTRE SINGAPORE Industrialisation, Jurong and the making of modern Singapore Goh’s folly? Housing and building a liveable Jurong 5. FORMER JURONG TOWN HALL Heritage Sites in Jurong p. 44 Hawker centres in Jurong 6. JURONG RAILWAY Hong Kah Village Chew Boon Lay and the Peng Kang area 7. PANDAN RESERVOIR SAFTI Former Jurong Town Hall 8. JURONG HILL Jurong Port Jurong Shipyard Jurong Fishery Port 9. JURONG PORT AND SHIPYARD The Jurong Railway Jurong and Singapore’s waste management 10. -

NHB Jurong Trail Booklet Cover R5.Ai

Introduction p. 2 Jurong Bird Park (p. 64) ship berths and handled a diverse range of cargo including metals, Masjid Hasanah (p. 68) SAFTI (p. 51) Early History 2 Jurong Hill raw sugar, industrial chemicals and timber. The port is not open for 492 Teban Gardens Road 500 Upper Jurong Road public access. Historical extent of Jurong Jurong Railway (p. 58) The Orang Laut and Selat Samulun A remaining track can be found at Ulu Pandan Park Connector, Early accounts of Jurong between Clementi Ave 4 and 6 The gambier pioneers: opening up the interior Evolution of land use in Jurong Following Singapore’s independence in 1965, the Singapore Armed Growth of communities p. 18 Forces Training Institute (SAFTI) was established to provide formal training for officers to lead its armed forces. Formerly located at Pasir Villages and social life Laba Camp, the institute moved to its current premises in 1995. Navigating Jurong One of the most-loved places in Jurong, the Jurong Bird Park is the Following the resettlement of villagers from Jurong’s surrounding largest avian park in the Asia Pacific region with over 400 species islands in the 1960s, Masjid Hasanah was built to replace the old Science Centre Singapore (p. 67) Beginnings of industry of birds. suraus (small prayer houses) of the islands. With community 15 Science Centre Road Early educational institutions support, the mosque was rebuilt and reopened in 1996. Jurong Fishery Port (p. 57) Fishery Port Road Opened in 1966, Jurong Railway was another means to transport Nanyang University (p. 28) Tide of change: World War II p. -

98 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

98 bus time schedule & line map 98 Jurong East Int ↺ Jurong Island Checkpoint View In Website Mode The 98 bus line Jurong East Int ↺ Jurong Island Checkpoint has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Jurong East Int: 5:30 AM - 11:55 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 98 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 98 bus arriving. Direction: Jurong East Int 98 bus Time Schedule 69 stops Jurong East Int Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 5:30 AM - 11:55 PM Monday 5:30 AM - 11:55 PM Jurong Gateway Rd - Jurong East Int (28009) Gateway Link, Singapore Tuesday 5:30 AM - 11:55 PM Boon Lay Way - J Gateway (28061) Wednesday 5:30 AM - 11:55 PM Boon Lay Way, Singapore Thursday 5:30 AM - 11:55 PM Jurong East Ctrl - Blk 209 (28311) Friday 5:30 AM - 11:55 PM Jurong East Central, Singapore Saturday 5:30 AM - 11:55 PM Jurong East Ave 1 - Blk 239 (28321) 239 Jurong East Street 21, Singapore Jurong East Ave 1 - Blk 229 (28331) 229 Jurong East Street 21, Singapore 98 bus Info Direction: Jurong East Int Jurong East Ave 1 - Parc Oasis (28451) Stops: 69 Trip Duration: 103 min Jurong East Ave 1 - Blk 347 (28461) Line Summary: Jurong Gateway Rd - Jurong East Int (28009), Boon Lay Way - J Gateway (28061), Jurong East Ave 1 - Opp Jurong Polyclinic Jurong East Ctrl - Blk 209 (28311), Jurong East Ave (28491) 1 - Blk 239 (28321), Jurong East Ave 1 - Blk 229 (28331), Jurong East Ave 1 - Parc Oasis (28451), Jurong West Ave 1 - Blk 490 (28501) Jurong East Ave 1 - Blk 347 (28461), Jurong East 490 Jurong West Avenue 1, Singapore -

Journal No. 044/2012

2 November 2012 Trade Marks Journal No. 044/2012 TRADE MARKS JOURNAL TRADE MARKS JOURNAL SINGAPORE SINGAPORE TRADE PATENTS TRADE DESIGNS PATENTS MARKS DESIGNS MARKS PLANT VARIETIES © 2012 Intellectual Property Office of Singapore. All rights reserved. Reproduction or modification of any portion of this Journal without the permission of IPOS is prohibited. Intelle ctual Property Office of Singapore 51 Bras Basah Road #04-01, Manulife Centre Singapore 189554 Tel: (65) 63398616 Fax: (65) 63390252 http://www.ipos.gov.sg Trade Marks Journal No. 044/2012 TRADE MARKS JOURNAL Published in accordance with Rule 86A of the Trade Marks Rules. Contents Page 1. General Information i 2. Practice Directions iii 3. Notices and Information (A) General xii (B) Collective and Certification Marks xxxiv (C) Forms xxxv (D) eTrademarks xxxix (E) International Applications and Registrations under the Madrid Protocol xli (F) Classification of Goods and Services xlvii (G) Circulars Related to Proceeding Before The Hearings And Mediation Division lxviii 4. Applications Published for Opposition Purposes (Trade Marks Act, Cap. 332, 1999 Ed.) 1 5. International Registrations filed under the Madrid Protocol Published for Opposition Purposes (Trade Marks Act, Cap. 332, 1999 Ed.) 177 Trade Marks Journal No. 044/2012 Information Contained in This Journal The Registry of Trade Marks does not guarantee the accuracy of its publications, data records or advice nor accept any responsibility for errors or omissions or their consequences. Permission to reproduce extracts from this Journal must be obtained from the Registrar of Trade Marks. Trade Marks Journal No. 044/2012 Page No. i GENERAL INFORMATION References to “section” and “rule” in these notes are references to that section of the Trade Marks Act (Cap. -

List of Approved Providers for Antigen Rapid Testing for COVID-19 Within

List of Approved Providers for Antigen Rapid Testing for COVID-19 within their Healthcare Institutions (HCIs) NOTE: The fees published in this list are as per HCI’s declaration and may be subject to change by the HCI from time to time. Please call the clinic to ensure that they are able to offer private-paid ART swabs. List updated as at 13 Aug 2021. HCI Name HCI Address Operating Hours Age Contact No Fees Charged Start Date Group Per Test* 1 BISHAN MEDICAL Blk 283 Bishan Street 22 8am to 2pm, 6pm to 11pm Daily 7 and 64561600 $53.50 11 May 2021 #01-191 S(570283) (Public Holidays inclusive, but to call and above check if any change in hours) 1 MEDICAL TECK GHEE BLK 410 ANG MO KIO Mon - Sun (including PH): All ages 62517030 $42.80 24 Apr 2021 AVENUE 10 #01-837 TECK 07.00am to 01.00pm GHEE SQUARE S(560410) 06.00pm to 11.00pm 216 PROCROSS MEDICAL Blk 216 Boon Lay Avenue Mon-Fri: 9.30am-12pm; 12.30pm-3pm; 4- All ages 67022848 $90 15 May 2021 CLINIC #01-03 Multi Storey Car 7pm Park S(640216) Sat/Sun: 12.30pm-3pm 338 FAMILY CLINIC Blk 338 Ang Mo Kio Ave 1 SASH from Mon - Thur, Sat: 10am - 1pm 7 and 64549408 To call clinic 17 May 2021 #01-1615 S(560338) above 405 PROCROSS MEDICAL Blk 405 Jurong West Street Mon-Fri- 9.30am-12pm; 12.30pm-3pm; All ages 67022848 $90 21 May 2021 CLINIC 42 #01-K1 Hong Kah Court 4pm-7pm S(640405) Sat/Sun: 12.30pm-3pm 411 PROCROSS MEDICAL Blk 411 Jurong West Street Mon-Fri- 9.30am-12pm; 12.30pm-3pm; All ages 67022848 $90 21 May 2021 CLINIC 42 #01-K1 S(640411) 4pm-7pm Sat/Sun: 12.30pm-3pm 57 MEDICAL CLINIC (GEYLANG BLK -

180 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

180 bus time schedule & line map 180 Boon Lay Int View In Website Mode The 180 bus line Boon Lay Int has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Boon Lay Int: 5:20 AM - 11:39 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 180 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 180 bus arriving. Direction: Boon Lay Int 180 bus Time Schedule 47 stops Boon Lay Int Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 5:30 AM - 11:38 PM Monday 5:20 AM - 11:39 PM Jurong West Ctrl 3 - Boon Lay Int (22009) 61 Jurong West Central 3, Singapore Tuesday 5:20 AM - 11:39 PM Jurong West St 64 - Opp Blk 662c (22499) Wednesday 5:20 AM - 11:39 PM Boon Lay Way - Summerdale (21699) Thursday 5:20 AM - 11:39 PM Friday 5:20 AM - 11:39 PM Boon Lay Way - Blk 200 (21689) 196B Boon Lay Drive, Singapore Saturday 5:20 AM - 11:39 PM Boon Lay Way - Opp Lakeside Stn (28099) 517E Jurong West Street 52, Singapore Boon Lay Way - Aft Jurong West St 51 (28379) 180 bus Info Direction: Boon Lay Int Boon Lay Way - Opp Jurong Lake (28369) Stops: 47 7 Jurong West Street 41, Singapore Trip Duration: 80 min Line Summary: Jurong West Ctrl 3 - Boon Lay Int Boon Lay Way - Blk 350 (28359) (22009), Jurong West St 64 - Opp Blk 662c (22499), 350 Jurong East Avenue 1, Singapore Boon Lay Way - Summerdale (21699), Boon Lay Way - Blk 200 (21689), Boon Lay Way - Opp Lakeside Stn Boon Lay Way - Opp Chinese Gdn Stn (28349) (28099), Boon Lay Way - Aft Jurong West St 51 (28379), Boon Lay Way - Opp Jurong Lake (28369), Jurong Town Hall Rd - Opp Blk 227 (28281) Boon Lay Way - Blk 350 (28359), -

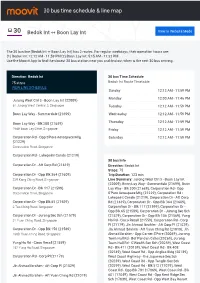

30 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

30 bus time schedule & line map 30 Bedok Int ↔ Boon Lay Int View In Website Mode The 30 bus line (Bedok Int ↔ Boon Lay Int) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bedok Int: 12:12 AM - 11:59 PM (2) Boon Lay Int: 5:15 AM - 11:32 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 30 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 30 bus arriving. Direction: Bedok Int 30 bus Time Schedule 75 stops Bedok Int Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:12 AM - 11:59 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:46 PM Jurong West Ctrl 3 - Boon Lay Int (22009) 61 Jurong West Central 3, Singapore Tuesday 12:12 AM - 11:59 PM Boon Lay Way - Summerdale (21699) Wednesday 12:12 AM - 11:59 PM Boon Lay Way - Blk 200 (21689) Thursday 12:12 AM - 11:59 PM 196B Boon Lay Drive, Singapore Friday 12:12 AM - 11:59 PM Corporation Rd - Opp S'Pore Aerospace Mfg Saturday 12:12 AM - 11:59 PM (21229) Corporation Road, Singapore Corporation Rd - Lakepoint Condo (21219) 30 bus Info Corporation Dr - Aft Corp Rd (21619) Direction: Bedok Int Stops: 75 Corporation Dr - Opp Blk 364 (21609) Trip Duration: 123 min 339 Kang Ching Road, Singapore Line Summary: Jurong West Ctrl 3 - Boon Lay Int (22009), Boon Lay Way - Summerdale (21699), Boon Corporation Dr - Blk 117 (21599) Lay Way - Blk 200 (21689), Corporation Rd - Opp Corporation Drive, Singapore S'Pore Aerospace Mfg (21229), Corporation Rd - Lakepoint Condo (21219), Corporation Dr - Aft Corp Corporation Dr - Opp Blk 65 (21589) Rd (21619), Corporation Dr - Opp Blk 364 (21609), 2 Tao Ching Road, Singapore Corporation Dr - -

ANNEX B Locations of the 120 Digital Traffic Red Light Cameras S/N Location 1 Adam Road by Sime Road Towards Lornie Road 2 Admi

ANNEX B Locations of the 120 Digital Traffic Red Light Cameras S/N Location 1 Adam Road by Sime Road towards Lornie Road 2 Admiralty Road by Marsiling Lane towards Woodlands Centre Road Admiralty Road by Woodlands Centre Road towards Bukit Timah 3 Expressway 4 Airport Road by Ubi Ave 2 towards Macpherson Road 5 Alexandra Road by Commonwealth Ave towards Tiong Bahru Road 6 Ang Mo Kio Ave 1 by Ang Mo Kio Ave 10 towards Lor Chuan 7 Ang Mo Kio Ave 1 by Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 towards Ang Mo Kio Ave 8 8 Ang Mo Kio Ave 1 by Central Expressway towards Ang Mo Kio Ave 10 9 Ang Mo Kio Ave 1 by Central Expressway towards Lor Chuan 10 Ang Mo Kio Ave 1 by Lor Chuan towards Boundary Road 11 Ang Mo Kio Ave 1 by Marymount Rd towards Upper Thomson Road Ang Mo Kio Ave 3 by Ang Mo Kio Industrial Park 2 towards Central 12 Expressway 13 Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 by Ang Mo Kio Ave 5 towards Ang Mo Kio Ave 3 14 Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 by Ang Mo Kio Ave 5 towards Lentor Ave 15 Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 by Ang Mo Kio Ave 8 towards Ang Mo Kio Ave 5 16 Ang Mo Kio Ave 8 by Ang Mo Kio Ave 3 towards Ang Mo Kio Ave 5 Bedok North Ave 1 by Bedok North Street 1 towards New Upper 17 Changi Road 18 Bedok Reservoir Road by Bedok North Ave 3 towards Tampines Ave 4 Bedok South Ave 1 by Bedok South Road towards Upper East Coast 19 Road 20 Bishan Street 11 by Bishan Street 12 towards Bishan Street 21 21 Boon Lay Drive by Corporation Road towards Boon Lay Way 22 Boon Lay Way by Jurong East Central towards Jurong Town Hall Road 23 Brickland Road by Choa Chu Kang Ave 3 towards Bukit Batok Road Bukit Batok East