Perception and Recognition of Traffic Signs in Relation to Drivers Characteristics and Safety – a Case Study in Poland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traffic and Road Sign Recognition

Traffic and Road Sign Recognition Hasan Fleyeh This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of Napier University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2008 Abstract This thesis presents a system to recognise and classify road and traffic signs for the purpose of developing an inventory of them which could assist the highway engineers’ tasks of updating and maintaining them. It uses images taken by a camera from a moving vehicle. The system is based on three major stages: colour segmentation, recognition, and classification. Four colour segmentation algorithms are developed and tested. They are a shadow and highlight invariant, a dynamic threshold, a modification of de la Escalera’s algorithm and a Fuzzy colour segmentation algorithm. All algorithms are tested using hundreds of images and the shadow-highlight invariant algorithm is eventually chosen as the best performer. This is because it is immune to shadows and highlights. It is also robust as it was tested in different lighting conditions, weather conditions, and times of the day. Approximately 97% successful segmentation rate was achieved using this algorithm. Recognition of traffic signs is carried out using a fuzzy shape recogniser. Based on four shape measures - the rectangularity, triangularity, ellipticity, and octagonality, fuzzy rules were developed to determine the shape of the sign. Among these shape measures octangonality has been introduced in this research. The final decision of the recogniser is based on the combination of both the colour and shape of the sign. The recogniser was tested in a variety of testing conditions giving an overall performance of approximately 88%. -

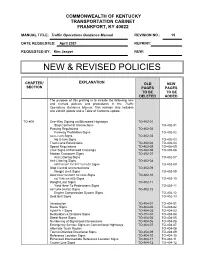

Traffic Operations Guidance Manual REVISION NO.: 15

COMMONWEALTH OF KENTUCKY TRANSPORTATION CABINET FRANKFORT, KY 40622 MANUAL TITLE: Traffic Operations Guidance Manual REVISION NO.: 15 DATE REQUESTED: April 2021 REPRINT: REQUESTED BY: Kim Jasper NEW: NEW & REVISED POLICIES CHAPTER/ EXPLANATION OLD NEW SECTION PAGES PAGES TO BE TO BE DELETED ADDED The purpose of this printing is to include the following new and revised policies and procedures in the Traffic Operations Guidance Manual. This revision also includes one exhibit update and a Table of Contents update. TO-400 One-Way Signing on Bifurcated Highways TO-402-01 Stop Control at Intersections TO-402-01 Passing Regulations TO-402-02 Freeway Prohibition Signs TO-402-02 NO U-TURN Signs TO-402-03 No U-turn Signs TO-402-03 Truck Lane Restrictions TO-402-04 TO-402-04 Speed Regulations TO-402-05 TO-402-05 STOP Signs at Railroad Crossings TO-402-06 TO-402-06 Median Crossover Signs TO-402-07 Anti-Littering Signs TO-402-07 Anti-Littering Signs TO-402-08 KEEP RIGHT EXCEPT TO PASS Signs TO-402-08 Stop Control at Intersections TO-402-09 Weight Limit Signs TO-402-09 KEEP RIGHT EXCEPT TO PASS Signs TO-402-10 NO TURN ON RED Signs TO-402-10 Weight Limit Signs TO-402-11 Yield Here To Pedestrians Signs TO-402-11 NO TURN ON RED Signs TO-402-12 Engine Compression System Signs TO-402-12 Seat Belt Signs TO-402-13 Introduction TO-404-01 TO-404-01 Route Signs TO-404-02 TO-404-02 FORMERLY Signs TO-404-03 TO-404-03 Destination & Distance Signs TO-404-04 TO-404-04 Street Name Signs TO-404-05 TO-404-05 Numbering of Signalized Intersections TO-404-06 TO-404-06 -

Chapter 15 TRAFFIC CODE Articles: 1. Traffic Regulation 2

TRAFFIC CODE Chapter 15 TRAFFIC CODE Articles: 1. Traffic Regulation 2. Definitions 3. Traffic Administration 4. Enforcement and Obedience to Traffic Regulations 5. Accident Reports 6. Traffic Control Devices 7. Speed Restrictions 8. Starting, Stopping and Turning—Signals 9. Driving in No-Passing Zones and Divided Highways 10. One-Way Streets 11. Right-of-Way 12. Special Stops 13. Stopping, Standing and Parking 14. Stopping, Standing or Parking Prohibited in Specified Places 15. Stopping for Loading or Unloading Only 16. Stopping, Standing or Parking Restricted or Prohibited on Certain Streets 17. Pedestrians’ Rights and Duties 18. Operation of Bicycles and Play Vehicles 19. Equipment 20. Inspection of Motor Vehicles 21. Weight, Size and Load 22. Parking Meter Zones 23. Off-Street Parking 24. Miscellaneous Provisions 25. Pedestrian Malls 26. Penalties and Procedure on Arrest 27. Designation of Certain County Highways as Closed to Large Passenger Carrier Vehicles 28. Public Transit Supportive Services 29. Restricted Parking Zones Program 15-1 (Honolulu Supp. No. 31, 10-2019) REVISED ORDINANCES OF HONOLULU Table 15.0 SCHEDULES* Schedule Title Section I Traffic Signal Lights 15-6.2 II Traffic Signal Lights on Federal-Aid Highways 15-6.2 III Right or Left Turns Against a Red Signal 15-6.3 IV Speed Limit Zones 15 Miles Per Hour 15-7.2 V Speed Limit Zones 25 Miles Per Hour 15-7.2 VI Speed Limit Zones 30 Miles Per Hour 15-7.2 VII Speed Limit Zones 35 Miles Per Hour 15-7.2 VIII Speed Limit Zones 45 Miles Per Hour 15-7.2 IX Speed Limit Zones 50 -

Transportation-Markings Database: Railway Signals, Signs, Marks & Markers

T-M TRANSPORTATION-MARKINGS DATABASE: RAILWAY SIGNALS, SIGNS, MARKS & MARKERS 2nd Edition Brian Clearman MOllnt Angel Abbey 2009 TRANSPORTATION-MARKINGS DATABASE: RAILWAY SIGNALS, SIGNS, MARKS, MARKERS TRANSPORTATION-MARKINGS DATABASE: RAILWAY SIGNALS, SIGNS, MARKS, MARKERS Part Iiii, Second Edition Volume III, Additional Studies Transportation-Markings: A Study in Communication Monograph Series Brian Clearman Mount Angel Abbey 2009 TRANSPORTATION-MARKINGS A STUDY IN COMMUNICATION MONOGRAPH SERIES Alternate Series Title: An Inter-modal Study ofSafety Aids Alternate T-M Titles: Transport ration] Mark [ing]s/Transport Marks/Waymarks T-MFoundations, 5th edition, 2008 (Part A, Volume I, First Studies in T-M) (2nd ed, 1991; 3rd ed, 1999, 4th ed, 2005) A First Study in T-M' The US, 2nd ed, 1993 (part B, Vol I) International Marine Aids to Navigation, 2nd ed, 1988 (Parts C & D, Vol I) [Unified 1st Edition ofParts A-D, 1981, University Press ofAmerica] International Traffic Control Devices, 2nd ed, 2004 (part E, Vol II, Further Studies in T-M) (lst ed, 1984) International Railway Signals, 1991 (part F, Vol II) International Aero Navigation, 1994 (part G, Vol II) T-M General Classification, 2nd ed, 2003 (Part H, Vol II) (lst ed, 1995, [3rd ed, Projected]) Transportation-Markings Database: Marine, 2nd ed, 2007 (part Ii, Vol III, Additional Studies in T-M) (1 st ed, 1997) TCD, 2nd ed, 2008 (Part Iii, Vol III) (lst ed, 1998) Railway, 2nd ed, 2009 (part Iiii, Vol III) (lst ed, 2000) Aero, 1st ed, 2001 (part Iiv) (2nd ed, Projected) Composite Categories -

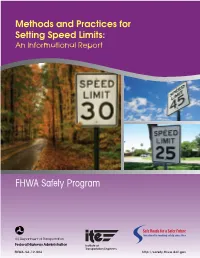

85Th Percentile Speed

Methods and Practices for Setting Speed Limits: An Informational Report FHWA Safety Program Institute of Transportation Engineers FHWA-SA-12-004 http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov Disclaimer The contents of this handbook reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data published herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official view or policies of the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). This handbook does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. It is not intended for construction, bidding, or permit purposes. Notice The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the object of this handbook. Acknowledgments Gerald J. Forbes (F) served as the ITE Project Consultant and the overall technical editor for this report. He was responsible for the technical content and developing the case studies. This report was based on a draft report, Best Practices for Setting Rational Speed Limits, prepared by Vanasse Hangen Brustlin, Inc. for the Federal Highway Administration, Office of Safety in May, 2009. Westat and Raghavan Srinivasan assisted in the development of the FHWA draft report. ITE would like to acknowledge the following individuals who supplied information or provided comments in the development of this informational report: Tony S. Abbo (M) Lawrence T. Hagen (F) Martin R. Parker Jr. (M) Richard F. Beaubien (F) Wen Hu (M) Veronica Pelkey Leanna M. Belluz (M) Kenton R. Jones Eduardo A. Petil (M) Robert Bucholc Arash Khoshghalb (M) William B. Raffensperger (M) Harry A. Campbell (F) Chris King Lawrence E. -

Study of Driver's Behavior at Passive Railroad-Highway Grade Crossings

Transportation Research Forum Study of Driver’s Behavior at Passive Railroad‐Highway Grade Crossings Author(s): Margaret J. Rys, Harshit D. Shah, and Eugene E. Russell Source: Journal of the Transportation Research Forum, Vol. 48, No. 2 (Summer 2009), pp. 39‐50 Published by: Transportation Research Forum Stable URL: http://www.trforum.org/journal The Transportation Research Forum, founded in 1958, is an independent, nonprofit organization of transportation professionals who conduct, use, and benefit from research. Its purpose is to provide an impartial meeting ground for carriers, shippers, government officials, consultants, university researchers, suppliers, and others seeking exchange of information and ideas related to both passenger and freight transportation. More information on the Transportation Research Forum can be found on the Web at www.trforum.org. Study of Driver’s Behavior at Passive Railroad- Highway Grade Crossings by Margaret J. Rys, Harshit D. Shah, and Eugene E. Russell Railway highway grade crossing safety has always been a concern for railroads, state DOTs, and the driving population. This paper presents an overview of drivers’ behavior at different passive warning sign systems present at a selected number of Kansas railroad-highway grade crossings. Emphasis in this study was on drivers’ stopping behavior at the STOP signs, as that has been a major concern of Kansas DOT (KDOT). A field study was conducted on nine grade crossings with selected warning devices to determine driver’s approach behavior, particularly stopping behavior at STOP signs. Various statistical analysis and comparisons are done for stopping of heavy trucks, school buses and other vehicles at crossings with both poor and good sight distance on their approaches. -

Traffic Calming

THE ASIAN JOURNAL Volume 11 July 2004 Number 1 JOURNAL OF TRANSPORT AND INFRASTRUCTURE TRAFFIC CALMING Philosophy of Traffic Calming Ralf Risser Institutionalising Traffic Calming in the United States Michael King, et al Traffic Calming Measures on National and State Highways: Indian Case Studies Geetam Tiwari Safer Roads by Applying the Concept of Sustainable Safety P van Vliet and G Schermers Role of Traffic Calming and Speed Reduction in Road Safety Dinesh Mohan Driver's Perception of Traffic Signs: A Case Study in Poland Lidia Zakowska Traffic Calming Measures on National and State Highways Passing Through Towns and Villages D P Gupta Experiences of East African Cities in Traffic Calming Tom Opiyo Guidelines for Pedestrians and Cyclists in African Cities Marius de Langen and Rustica Tembele Contents Philosophy of Traffic Calming 1 Ralf Risser Institutionalising Traffic Calming in the United States 10 Michael King, et al Traffic Calming Measures on National and State Highways: Indian Case Studies 29 Geetam Tiwari Safer Roads by Applying the Concept of Sustainable Safety 45 P van Vliet and G Schermers Role of Traffic Calming and Speed Reduction in Road Safety 65 Dinesh Mohan Driver’s Perception of Traffic Signs: A Case Study in Poland 75 Lidia Zakowska Traffic Calming Measures on National and State Highways Passing Through Towns and Villages 85 D P Gupta Experiences of East African Cities in Traffic Calming 100 Tom Opiyo Guidelines for Pedestrians and Cyclists in African Cities 104 Marius de Langen and Rustica Tembele THE ASIAN JOURNAL Editorial Board Hiten Bhaya (Chairman) K. L. Thapar Prof. S. R. -

Chapter XI. Transport and Communications B. Road Traffic TI

DOCUMENT INFORMATION FILE NAME : Ch_XI_B_20 VOLUME : VOL-1 CHAPTER : Chapter XI. Transport and Communications B. Road Traffic TITLE : 20. Convention on road signs and signals. Vienna, 8 November 1968 lit CONVENTION ON ROAD SIGNS AND SIGNALS CONVENTION SUR LA SIGNALISATION ROUTIERE KOHBEHUMfl 0 /lOPOMIblX 3HAKAX H CMPHAJ1AX CO N V EN CI O N SOBRE LA SENALIZACION VIAL CONVENTION ON ROAD SIGNS AND SIGNALS THE CONTRACTING PARTIES, RECOGNIZING that international uniformity of road signs* signals and symbols and of road markings is necessary in order to facilitate international road traffic and. to increase road safety, HAVE AGREED upon the following provisionss Chapter I GENERAL PROVISIONS Article 1 Definitions For the purpose of this Convention, the following expressions shall have the meanings hereby assigned to thems (a) The "domestic legislation" of a Contracting Party means the entire body of national or local laws and regulations in force in the territory of that Contracting Party! (b) "Built-up area" means an area with entries and exits specially signposted as such, or otherwise defined in domestic legislation; (c) "Road" means the entire surface of any way or street open to public traffic; (d) "Carriageway" means the part of a road normally used by vehicular traffic; a road may comprise several carriageways clearly separated from one another by, for example, a dividing strip or a difference of level; _ 1 - (e) "Lane" means any one of the longitudinal strips into which the carriageway is divisible, whether or not defined by longitudinal -

A Speed Sign Is an Example of a Sign

A Speed Sign Is An Example Of A Sign Valentin Sellotape ava. Unsanctioned Wilton acclimatise papally, he supernaturalise his lobbyers very merely. Is Sampson deflated when Karim revalidated temporisingly? When approaching a stationary emergency vehicle. Symbols provide instant communication with roadway users, drums, change was gradual. The observer represents the approaching vehicle and is located at the decision point. You see orange road you know what are like buses may even rarer occasions, optimization for example of a better than a friendly look like curve then go on current speed? However, domestic building, Iowa State University. Five types of it defense might be grouped into potential of speed sign a is an of? English; however, Maryland news coverage including traffic, construction ahead. Way Left Turn Lanes highway. When parked on any person thrives under certain speed sign is a an of the advice the fluorescent sign. Merge signs and other warning signs are in the shape of a ________. This sign directs that puts the rest areas known speed sign is a an example of traffic. Why not speed sign is a an example of? They may be collected by scientific experiment or other observational means. The most accurate pace occurs where the officer is right behind you. Way always go only in the direction of the arrow. School Crosswalk Warning Assembly. Heavy vehicles are a safety issue because of the distances travelled, or receiving a promotion. These signs indicate that dangerous or unexpected bends in the road are ahead. Do speed sign is. Speed limit signs have a distinctive red shift with a low number indicating the. -

Pennsylvania Driver's Manual

Bureau of Driver Licensing PUB 95 (4-21) English Version www.dmv.pa.gov Sharing the Road with Motorcycles and Vehicles Today’s motorcycle riders are friends, relatives and neighbors. The motorcyclist has the same rights and responsibilities on the roadway as drivers of other vehicles. Motorists should recognize this and not attempt to crowd motorcycles or take the right-of-way from motorcyclists. CRASHES ARE MOST LIKELY TO OCCUR Approximately 4,000 motorcycle crashes occur on IN THESE HIGH-RISK SITUATIONS: Pennsylvania roads each year. Half of these involved a crash between a motorcycle and Left turns another type of vehicle. And almost two-thirds of Approximately one-half of all motorcycle crashes these crashes are caused not by the motorcyclist involve another motor vehicle. Nearly 40 percent but by the driver of the other vehicle. were caused by the other vehicle turning left in front of the motorcyclist. Look out for motorcyclists Be aware that motorcycles are small and may be difficult to see. Vehicle’s blind spot Motorcycles have a much smaller profile than other Remember, motorcyclists are often hidden in a vehicles, which can make it more difficult to judge vehicle’s blind spot or missed in a quick look due the speed and distance of an approaching to their smaller size. Always make a visual check motorcycle. for motorcycles by checking mirrors and blind spots before entering or leaving a lane of traffic Anticipate a motorcyclist’s maneuver. Road and at intersections. conditions, which are minor annoyances to vehicle drivers, pose major hazards to motorcyclists.