Hetch Hetchy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sketch of Yosemite National Park and an Account of the Origin of the Yosemite and Hetch Hetchy Valleys

SKETCH OF YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK AND AN ACCOUNT OF THE ORIGIN OF THE YOSEMITE AND HETCH HETCHY VALLEYS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY 1912 This publication may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington. I). C, for LO cents. 2 SKETCH OP YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK AND ACCOUNT OF THE ORIGIN OF THE YOSEMITE AND HETCH HETCHY VALLEYS. By F. E. MATTHES, U. S. Geological Surrey. INTRODUCTION. Many people believe that the Yosemite National Park consists principally of the Yosemite Valley and its bordering heights. The name of the park, indeed, would seem to justify that belief, yet noth ing could be further from the truth. The Yosemite Valley, though by far the grandest feature of the region, occupies only a small part of the tract. The famous valley measures but a scant 7 miles in length; the park, on the other hand, comprises no less than 1,124 square miles, an area slightly larger than the State of Rhode Island, or about one-fourth as large as Connecticut. Within this area lie scores of lofty peaks and noble mountains, as well as many beautiful valleys and profound canyons; among others, the Iletch Hetchy Valley and the Tuolumne Canyon, each scarcely less wonderful than the Yosemite Valley itself. Here also are foaming rivers and cool, swift trout brooks; countless emerald lakes that reflect the granite peaks about them; and vast stretches of stately forest, in which many of the famous giant trees of California still survive. The Yosemite National Park lies near the crest of the great alpine range of California, the Sierra Nevada. -

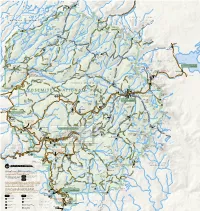

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK O C Y Lu H M Tioga Pass Entrance 9945Ft C Glen Aulin K T Ne Ee 3031M E R Hetc C Gaylor Lakes R H H Tioga Road Closed

123456789 il 395 ra T Dorothy Lake t s A Bond C re A Pass S KE LA c i f i c IN a TW P Tower Peak Barney STANISLAUS NATIONAL FOREST Mary Lake Lake Buckeye Pass Twin Lakes 9572ft EMIGRANT WILDERNESS 2917m k H e O e O r N V C O E Y R TOIYABE NATIONAL FOREST N Peeler B A Lake Crown B C Lake Haystack k Peak e e S Tilden r AW W Schofield C TO Rock Island OTH IL Peak Lake RI Pass DG D Styx E ER s Matterhorn Pass l l Peak N a Slide E Otter F a Mountain S Lake ri e S h Burro c D n Pass Many Island Richardson Peak a L Lake 9877ft R (summer only) IE 3010m F LE Whorl Wilma Lake k B Mountain e B e r U N Virginia Pass C T O Virginia S Y N Peak O N Y A Summit s N e k C k Lake k c A e a C i C e L C r N r Kibbie d YO N C n N CA Lake e ACK AI RRICK K J M KE ia in g IN ir A r V T e l N k l U e e pi N O r C S O M Y Lundy Lake L Piute Mountain N L te I 10541ft iu A T P L C I 3213m T Smedberg k (summer only) Lake e k re e C re Benson Benson C ek re Lake Lake Pass C Vernon Creek Mount k r e o Gibson e abe Upper an r Volunteer McC le Laurel C McCabe E Peak rn Lake u Lake N t M e cCa R R be D R A Lak D NO k Rodgers O I es e PLEASANT EA H N EL e Lake I r l Frog VALLEY R i E k G K C E LA e R a e T I r r Table Lake V North Peak T T C N Pettit Peak A INYO NATIONAL FOREST O 10788ft s Y 3288m M t ll N Fa s Roosevelt ia A e Mount Conness TILT r r Lake Saddlebag ILL VALLEY e C 12590ft (summer only) h C Lake ill c 3837m Lake Eleanor ilt n Wapama Falls T a (summer only) N S R I Virginia c A R i T Lake f N E i MIGUEL U G c HETCHY Rancheria Falls O N Highway 120 D a MEADOW -

AFTER the FLOODING - Montereyherald.Com : Page 1 of 2

AFTER THE FLOODING - MontereyHerald.com : Page 1 of 2 AFTER THE FLOODING entrance of the park. I never expected the drive along Evergreen Road Remnants of the Miwok people's ancestral land are to be such a visual treat with bucolic pockets of highlighted by frothy falls, breathtaking views meadows and vales rolling out to the forested foothills interrupted by meandering forks of the By LINDA B. MULLALLY Tuolumne River. Herald Correspondent The restored Evergreen Lodge and its compound of Updated: 08/30/2009 01:39:32 AM PDT rustic to classic cabins, custom camping facility, Maybe it was the exotic, sexy sound of "Hetch recreational activity center including bicycle rentals, Hetchy" that cast a spell on me. Year after year, every dining room with outdoor patio and fireside terrace new book and map fed my fascination for the Miwok beneath a canopy of pines exuded yesteryear Indians' ancestral land, tucked in the northwest Yosemite Valley, minus the world famous gem's corner of Yosemite National Park. Hetch Hetchy had hustle-bustle of human and vehicular traffic. become some mystical, legendary place in my mind. By 7 the next morning, David and I were first in line I was intrigued by the controversy surrounding the at Yosemite's Hetch Hetchy entrance, just 1 mile flooding of Hetch Hetchy Valley and John Muir's down the road past Camp Mather. The next 10 miles fight to save a place he thought as uniquely of paved serpentine roadway descended to a small beautiful as the "great Yosemite." According to parking lot and day use area at the face of the historical accounts, it was San Francisco's fast paced O'Shaughnessy Dam and Hetch Hetchy reservoir. -

Yosemite, Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks 5

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Yosemite, Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks Yosemite National Park p44 Around Yosemite National Park p134 Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks p165 Michael Grosberg, Jade Bremner PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Yosemite, YOSEMITE NATIONAL Tuolumne Meadows . 80 Sequoia & PARK . 44 Hetch Hetchy . 86 Kings Canyon . 4 Driving . 87 Yosemite, Sequoia & Day Hikes . 48 Kings Canyon Map . 6 Yosemite Valley . 48 Cycling . 87 Yosemite, Sequoia & Big Oak Flat Road Other Activities . 90 Kings Canyon Top 16 . 8 & Tioga Road . 56 Winter Activities . 95 Need to Know . 16 Glacier Point & Sights . 97 Badger Pass . 60 What’s New . 18 Yosemite Valley . 97 Tuolumne Meadows . 64 If You Like . 19 Glacier Point & Wawona . 68 Month by Month . 22 Badger Pass Region . 103 Hetch Hetchy . 70 Itineraries . 24 Tuolumne Meadows . 106 Activities . 28 Overnight Hikes . 72 Wawona . 109 Yosemite Valley . 74 Travel with Children . 36 Along Tioga Road . 112 Big Oak Flat & Travel with Pets . 41 Big Oak Flat Road . 114 Tioga Road . 75 Hetch Hetchy . 115 Glacier Point & Badger Pass . 78 Sleeping . 116 Yosemite Valley . 116 VEZZANI PHOTOGRAPHY/SHUTTERSTOCK © VEZZANI PHOTOGRAPHY/SHUTTERSTOCK DECEMBER35/SHUTTERSTOCK © NIGHT SKY, GLACIER POINT P104 PEGGY SELLS/SHUTTERSTOCK © SELLS/SHUTTERSTOCK PEGGY HORSETAIL FALL P103 VIEW FROM TUNNEL VIEW P45 Contents UNDERSTAND Yosemite, Sequoia & TAHA RAJA/500PX TAHA Kings Canyon Today . .. 208 History . 210 Geology . 216 © Wildlife . 221 Conservation . 228 SURVIVAL GUIDE VIEW OF HALF DOME FROM Clothing & GLACIER POINT P104 Equipment . 232 Directory A–Z . 236 Glacier Point & SEQUOIA & KINGS Badger Pass . 118 Transportation . 244 CANYON NATIONAL Health & Safety . 249 Big Oak Flat Road & PARKS . -

Restoring a Bridge to the Past a Message from the President

2005 Outdoor Adventure catalog enclosed! A JOURNAL FOR MEMBERS OF THE YOSEMITE ASSOCIATION Fall 2004 Volume 66 Number 4 Restoring a Bridge to the Past A Message from the President ave you seen the new Yosemite Association web cam that was installed recently below Sentinel Dome? The camera looks straight across at Half Dome and beyond to the Tuolumne high country. Views during the mid- October storms were really spectacular. Thanks to Vance Kozik and his associates at StarDot Technologies for donating the web cam and related equipment to our organization. I almost forgot. The address for the new “Sentinel Cam” is http://www.yosemite.org/vryos/sentinelcam.htm. While viewing live images of Yosemite over your computer may be entertaining, there’s nothing better than Hexperiencing the park in person. Make your next park visit a special one by participating in a Yosemite Outdoor Adventure course sponsored by YA. In this journal we’ve included the 2005 catalog that’s full of educational, stimu- lating, and (in some cases) challenging opportunities to better know your park. Members receive a 15% discount off course fees, and you can sign up online at www.yosemitestore.com. In this column I regularly brag about the amazing work done by YA volunteers every year in the park. We’re not the only ones who have noticed what a great job our volunteers are doing and how much they contribute to Yosemite. In August, long-term volunteer Virginia Ferguson was named winner of the thirteenth annual Yosemite Fund Award for her efforts as an “unsung hero.” She is certainly deserving of this recognition, and when she Cover: Wawona accepted the award, Virginia noted that she was sharing the honor with the hundreds of other YA volunteers. -

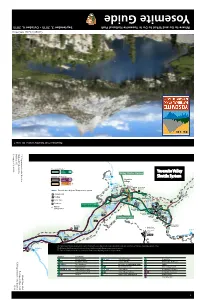

Yosemite Guide Yosemite

@YosemiteNPS Yosemite Guide Yosemite Photo by Christine Loberg Loberg Christine by Photo Yosemite National Park June 21, 2017 – July 25, 2017 Volume 42, Issue 5 Issue 42, Volume 2017 25, July – 2017 21, June Park National Yosemite America Your Experience Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Summer-only Route: Upper Shuttle System El Capitan Yosemite Shuttle Hetch Fall Yosemite Hetchy Village Campground Tuolumne Lower Yosemite Parking Meadows The Ansel Fall Adams l Medical Church Bowl i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area Picnic Area l T al F Yosemite e 5 t E1 Restroom i 4 Valley m 9 The Majestic Area in inset: se Yo Mirror Yosemite Valley Upper 10 3 Yosemite Hotel Walk-In 6 2 Lake Shuttle System seasonal Campground 11 1 Yosemite North Camp 4 8 Half Dome Valley Housekeeping Pines E2 Lower 8836 ft 7 Chapel Camp Wawona Yosemite Falls Parking Lodge Pines 2693 m Yosemite 18 19 Conservation 12 17 Heritage 20 14 Swinging Center (YCHC) Recreation Campground Bridge Rentals 13 Reservations Yosemite Village Parking 15 Pardon our dust! Shuttle service routes are Half Dome Upper Sentinel Village Pines subject to change as pavement rehabilitation Beach il Trailhead E7 a Half Dome Village Parking and road work is completed throughout 2017. r r T te Parking e n il i Expect temporary delays. w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l Mist Trai Cathedral ail Tr E4 op h Beach Lo or M ey ses erce all only d Ri V ver E6 Nevada Fall To & Bridalveil Fall d oa R B a r n id wo a Wa lv e The Yosemite Valley Shuttle operates from 7am to 10pm and serves stops in numerical order. -

Yosemite Guide Yosemite

Yosemite Guide Yosemite Where to Go and What to Do in Yosemite National Park September 2, 2015 - October 6, 2015 6, October - 2015 2, September Park National Yosemite in Do to What and Go to Where NPS Photo NPS Lake. Cathedral Volume 40, Issue 7 Issue 40, Volume America Your Experience Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Upper Summer-only Routes: Yosemite Shuttle System El Capitan Fall Yosemite Shuttle Village Express Lower Shuttle Yosemite The Ansel Fall Adams l Medical Church Bowl i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area l T al Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System F e E1 5 P2 t i 4 m e 9 Campground os Mirror r Y 3 Uppe 6 10 2 Lake Parking Village Day-use Parking seasonal The Ahwahnee Half Dome Picnic Area 11 P1 1 8836 ft North 2693 m Camp 4 Yosemite E2 Housekeeping Pines Restroom 8 Lodge Lower 7 Chapel Camp Lodge Day-use Parking Pines Walk-In (Open May 22, 2015) Campground LeConte 18 Memorial 12 21 19 Lodge 17 13a 20 14 Swinging Campground Bridge Recreation 13b Reservations Rentals Curry 15 Village Upper Sentinel Village Day-use Parking Pines Beach E7 il Trailhead a r r T te Parking e n il i w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l E4 Mist Trai Cathedral ail Tr op h Beach Lo or M ey ses erce all only d R V iver E6 Nevada To & Fall The Valley Visitor Shuttle operates from 7 am to 10 pm and serves stops in numerical order. -

Nearby Activities Features and Amenities of Yosemite Pines RV Resort and Family Lodging

Nearby fishing in the Sierras Guided Hiking Tours, Sightseeing Tours in Yosemite National Park. YFAguides.com Horseback Riding - Pine Mountain Lake Stables - Call in advance: (209) 962-8667. Features and Amenities of Yosemite Pines RV Resort and Family Lodging tinyurl.com/horseback-pml This guide with most current website links is also available on our website at: yosemitepinesrv.com/activities Several trail ride operators in Yosemite On-site Activities - Our resort offers lots of on-site features, and during the summer, Valley and Tuolumne Meadows area: our staff plans activities for the family Memorial Day through Labor Day. tinyurl.com/ynp-horseback-riding Located near our Swimming Pool Area: Swimming pool at Yosemite Pines Mountain Bike Riding - Groveland Ridge Playground Play Area Bocce Ball Courts Trail tinyurl.com/groveland-ridge-trail Games Area BBQ Area Sand Volleyball Court Deli/Clubhouse Winter Sports Activities - Snowshoeing and cross-country skiing in Glacier Point and Crane Flat area, and ice Tetherball Gold Panning Sluice Box skating at Half Dome Village in Yosemite Valley: Hayrides, Storytelling, Outdoor Movies - ask at office for times, tinyurl.com/ynp-winter-sports locations and other seasonal activities. Golf - Pine Mountain Lake Country Club - Semi-private golf course with on-site restaurant. See Yosemite Pines property map for location of Nature/Fitness (209) 962-8620 for tee times, (209) 962-8638 for restaurant reservations. tinyurl.com/pml-golfing Trails, Horseshoes and Petting Farm (ask office for feeding times). Please note that our pool and some other select amenities will be open no later than Memorial Day Weekend and close no sooner than 4WD Trails/OHV Riding Areas - Maps at Groveland Ranger Station, Highway 120 east of Ferretti Road. -

Yosemite Today

G 83 Third Class Mail Class Third Postage and Fee Paid Fee and Postage US Department Interior of the Park National Yosemite America Your Experience June – July 2008 July – June Guide Yosemite US Department Interior of the Service Park National 577 PO Box CA 95389 Yosemite, Experience Your America Yosemite National Park Vol.33, Issue No.1 Inside: 01 Welcome to Yosemite 09 Special Feature: Yosemite Secrets 10 Planning Your Trip 14 Programs and Events Jun-Jul 2008Highcountry Meadow. Photo by Ken Watson Where to Go and What to Do in Yosemite National Park June 11 – July 22 Yosemite Guide Experience Your America Yosemite National Park Yosemite Guide June – July 2008 Welcome to Yosemite Keep this Guide with you to Get the Most Out of Your Trip to Yosemite National Park park, then provide more detailed infor- mation on topics such as camping and hiking. Keep this guide with you as you make your way through the park. Pass it along to friends and family when you get home. Save it as a memento of your trip. This guide represents the collaborative energy of the National Park Service, The Yosemite Fund, DNC Parks & Resorts at Yosemite, Yosemite Association, The Ansel Adams Gallery, and Yosemite Institute—organizations Illustration by Lawrence W. Duke dedicated to Yosemite and to making your visit enjoyable and inspiring (see The Yosemite page 23). Experience National parks were established to John Muir once wrote, “As long as I preserve what is truly special about live, I’ll hear waterfalls and birds and Giant Sequoias. NPS Photo America. -

Our Spring Getaway Will Include Hiking in Yosemite National Park. We Will

Sun City Lincoln Hills Pine Mountain Lake/ Yosemite Getaway. Monday May 21, 2018- Thursday May 24, 2018 Preliminary information, specifics to follow next year Our spring getaway will include hiking in Yosemite National Park. We will be staying in Pine Mountain Lake, Groveland, CA, a gated community approximately 25 minutes from the 120 Gate into Yosemite National Park. It will take you approximately 2.5-3 hours to reach PML from LH. We will be renting various homes throughout this community. The community, first developed in the 60’s, has a lake, swimming pool, tennis courts, pickle ball courts, stables, airport, golf course and country club restaurant. Your lodging is spread throughout this small development. Lodging Regarding the lodging, I recommend that you research and book the homes ASAP since they are currently being held for our group only for a short time. I have contacted Pat Borogan who has 7 large homes in PML. She will be your rental contact person. Please contact her directly and not through Airbnb so that our hiking group can receive a discount. Most of the homes are $350 or less per night not including our discount. First, you will need to decide who you want to stay with in your rental home since most homes are quite large. Expect to have your own bedroom and private bath, then share the kitchen and living room. One home even has two kitchens and a kitchenette. Next, designate one person per rental house to contact Pat Borogan and coordinate the rental contract, finances, etc Incidentally, Pat is a hiker with Groveland Sierra Club, a group I hike with. -

Yosemite Foundation Document

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Yosemite National Park California December 2016 Foundation Document k e k e e r e C r Upper C n Yosemite o h y c r Fall n k A a e C e l r Yosemite Point a n C 6936ft y a Lower o 2114m i North Dome e d R t 7525ft i Yosemite n I 2294m m Fall e s ek o re Y U.S. Yosemite Valley Visitor Center C ya Court a Wilderness Center n e Museum Royal Arch T Lower Yosemite Medical Clinic Cascade Fall Trail Washington Columbia YOSEMITE Column Mirror Rock VILLAGE ROYAL Eagle Lake T ARCHES 4094ft Peak H 1248m 7779ft R The Ahwahnee Half Dome 2371m Sentinel Visitor E 8836ft Bridge Parking E North 2693m B Housekeeping Pines Camp 4 R Yosemite Camp Lower O Lodge Pines Chapel Stoneman T Bridge Middle H LeConte Brother E Memorial Road open ONLY to R Lodge pedestrians, bicycles, Ribbon S Visitor Parking and vehicles with Fall Swinging Bridge Curry Village Upper wheelchair emblem Pines Lower placards Sentinel Little Yosemite Valley El Capitan Brother Beach Trailhead for Moran 7569ft Four Mile Trail (summer only) R Point Staircase Mt Broderick i 2307m Trailhead 6706ft 6100 ft b Falls Horse Tail Parking 1859m b 2044m o Fall Trailhead for Vernal n Fall, Nevada Fall, and Glacier Point El Capitan Vernal C 7214 ft Nature Center John Muir Trail r S e e 2199 m at Happy Isles Fall Liberty Cap e n r k t 5044ft 7076ft ve i 4035ft Grizzly Emerald Ri n rced e 1230m 1538m 2157m Me l Peak Pool Silver C Northside Drive ive re Sentinel Apron Dr e North one-way Cathedral k El Capitan e Falls 0 0.5 Kilometer -

Yosemap1.Pdf

Dorothy Lake Pass Emigrant il Lake ra T Dorothy Lake k Bond e e r Pass C S E Maxwell t K s A Lake L e r C y r r e Tower N h I C TW Peak STANISLAUS NATIONAL FOREST c Mary Barney fi Lake HUMBOLDT-TOIYABE i Buckeye Pass Lake Huckleberry c 9572 ft Lake a P 2917 m H EMIGRANT WILDERNESS Twin Lakes O NATIONAL FOREST O N V O Peeler E Y Lake R k N Crown e Lake e A k r rk C e W o Haystack C e F r I Rock Tilden Peak C AW t S TO L s O a Island T E Lake H D Schofield Matterhorn Styx Pass R s E I l D Peak l G Peak Pass D ia R a L r E F N E e Slide Otter I h F c Burro E Lake n Mountain Green E a Pass S Lake Richardson Peak (staffed L R S Many 9877 ft B Island intermittently) B 3010 m Lake k U Whorl e Wilma Lake T e r S Mountain C Virginia Pass N N O Virginia O k Y e Y e Peak Summit N r s N A C Lake e k k c C i A a r N L C O Kibbie Y d N CA Lake n AI N ERRICK a 167 M K e i K K r n C i A e rg J N l i I l V i A T p N S N k O U e re Y (staffed intermittently) O To C N Piute M A Carson City, Nev.