Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Being a Thesis Submitted for the Degree Of

The tJni'ers1ty of Sheffield Depaz'tient of Uistory YORKSRIRB POLITICS, 1658 - 1688 being a ThesIs submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by CIthJUL IARGARRT KKI August, 1990 For my parents N One of my greater refreshments is to reflect our friendship. "* * Sir Henry Goodricke to Sir Sohn Reresby, n.d., Kxbr. 1/99. COff TENTS Ackn owl edgements I Summary ii Abbreviations iii p Introduction 1 Chapter One : Richard Cromwell, Breakdown and the 21 Restoration of Monarchy: September 1658 - May 1660 Chapter Two : Towards Settlement: 1660 - 1667 63 Chapter Three Loyalty and Opposition: 1668 - 1678 119 Chapter Four : Crisis and Re-adjustment: 1679 - 1685 191 Chapter Five : James II and Breakdown: 1685 - 1688 301 Conclusion 382 Appendix: Yorkshire )fembers of the Coir,ons 393 1679-1681 lotes 396 Bibliography 469 -i- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Research for this thesis was supported by a grant from the Department of Education and Science. I am grateful to the University of Sheffield, particularly the History Department, for the use of their facilities during my time as a post-graduate student there. Professor Anthony Fletcher has been constantly encouraging and supportive, as well as a great friend, since I began the research under his supervision. I am indebted to him for continuing to supervise my work even after he left Sheffield to take a Chair at Durham University. Following Anthony's departure from Sheffield, Professor Patrick Collinson and Dr Mark Greengrass kindly became my surrogate supervisors. Members of Sheffield History Department's Early Modern Seminar Group were a source of encouragement in the early days of my research. -

HISTORY MEDIUM TERM PLAN (MTP) YEAR 4 2020: Taught 1St Half of Each Term HISTORY MTP Y4 Autumn 1: 8 WEEKS Spring 1: 6 WEEKS Su

HISTORY MEDIUM TERM PLAN (MTP) YEAR 4 2020: Taught 1st half of each term HISTORY Autumn 1: 8 WEEKS Spring 1: 6 WEEKS Summer 1: 6 WEEKS MTP Y4 Topic Title: Anglo-Saxons / Scots Topic Title: Vikings Topic Title: UK Parliament Taken from the Year Key knowledge: Key knowledge: Key knowledge: group • Roman withdrawal from Britain in CE • Viking raids and the resistance of Alfred the Great and • Establishment of the parliament - division of the curriculum 410 and the fall of the western Roman Athelstan. Houses of Lords and Commons. map Empire. • Edward the Confessor and his death in 1066 - prelude to • Scots invasions from Ireland to north the Battle of Hastings. Key Skills: Britain (now Scotland). • Anglo-Saxons invasions, settlements and Key Skills: kingdoms; place names and village life • Choose reliable sources of information to find out culture and Christianity (eg. Canterbury, about the past. Iona, and Lindisfarne) • Choose reliable sources of information to find out about • Give own reasons why changes may have occurred, the past. backed up by evidence. • Give own reasons why changes may have occurred, • Describe similarities and differences between people, Key Skills: backed up by evidence. events and artefacts. • Describe similarities and differences between people, • Describe how historical events affect/influence life • Choose reliable sources of information events and artefacts. today. to find out about the past. • Describe how historical events affect/influence life today. Chronological understanding • Give own reasons why changes may Chronological understanding • Understand that a timeline can be divided into BCE have occurred, backed up by evidence. • Understand that a timeline can be divided into BCE and and CE. -

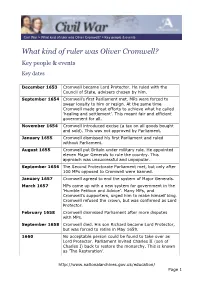

What Kind of Ruler Was Oliver Cromwell? > Key People & Events

Civil War > What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? > Key people & events What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? Key people & events Key dates December 1653 Cromwell became Lord Protector. He ruled with the Council of State, advisers chosen by him. September 1654 Cromwell’s first Parliament met. MPs were forced to swear loyalty to him or resign. At the same time Cromwell made great efforts to achieve what he called ‘healing and settlement’. This meant fair and efficient government for all. November 1654 Cromwell introduced excise (a tax on all goods bought and sold). This was not approved by Parliament. January 1655 Cromwell dismissed his first Parliament and ruled without Parliament. August 1655 Cromwell put Britain under military rule. He appointed eleven Major Generals to rule the country. This approach was unsuccessful and unpopular. September 1656 The Second Protectorate Parliament met, but only after 100 MPs opposed to Cromwell were banned. January 1657 Cromwell agreed to end the system of Major Generals. March 1657 MPs came up with a new system for government in the ‘Humble Petition and Advice’. Many MPs, and Cromwell’s supporters, urged him to make himself king. Cromwell refused the crown, but was confirmed as Lord Protector. February 1658 Cromwell dismissed Parliament after more disputes with MPs. September 1658 Cromwell died. His son Richard became Lord Protector, but was forced to retire in May 1659. 1660 No acceptable person could be found to take over as Lord Protector. Parliament invited Charles II (son of Charles I) back to restore the monarchy. This is known as ‘The Restoration’. -

Notes on Political Poems Ca. 1640

Studies in English Volume 1 Article 13 1960 Notes on Political Poems ca. 1640 Charles L. Hamilton University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ms_studies_eng Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Hamilton, Charles L. (1960) "Notes on Political Poems ca. 1640," Studies in English: Vol. 1 , Article 13. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ms_studies_eng/vol1/iss1/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in English by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hamilton: Notes on Political Poems Notes on Political Poems, c. 1640 Charles L. Hamilton HET CIVILwars in England and Scotland during the seventeenth century produced a wealth of popular literature. Some of it has permanent literary merit, but a large share of the popular creations, especially of the poetry, was little more than bad doggerel. Even so, one little-known and two unpublished poems such as the following are important as a guide to public opinion. From the period of the Bishops’ Wars (1638-40) the Scottish Covenanters repeatedly urged the English to abolish episcopacy and to enter a religious union with them.1 The following poem, written very likely on the eve of the meeting of the Long Parliament, exem plifies the Scottish feeling very clearly: Oyes, Oyes do I Cry The Bishops’ Bridles Will ye Buy2 Since Bishops first began to ride, In state so near the crown They have been aye puffed up with pride And ride with great renown. -

Why Did Britain Become a Republic? > New Government

Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Why did Britain become a republic? Case study 2: New government Even today many people are not aware that Britain was ever a republic. After Charles I was put to death in 1649, a monarch no longer led the country. Instead people dreamed up ideas and made plans for a different form of government. Find out more from these documents about what happened next. Report on the An account of the Poem on the arrest of setting up of the new situation in Levellers, 1649 Commonwealth England, 1649 Portrait & symbols of Cromwell at the The setting up of Cromwell & the Battle of the Instrument Commonwealth Worcester, 1651 of Government http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/ Page 1 Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Case study 2: New government - Source 1 A report on the arrest of some Levellers, 29 March 1649 (Catalogue ref: SP 25/62, pp.134-5) What is this source? This is a report from a committee of MPs to Parliament. It explains their actions against the leaders of the Levellers. One of the men they arrested was John Lilburne, a key figure in the Leveller movement. What’s the background to this source? Before the war of the 1640s it was difficult and dangerous to come up with new ideas and try to publish them. However, during the Civil War censorship was not strongly enforced. Many political groups emerged with new ideas at this time. One of the most radical (extreme) groups was the Levellers. -

1 Law and the Construction of Policy. a Comparative Analysis Edward C

Law and the Construction of Policy. A Comparative Analysis Edward C Page Department of Government, London School of Economics and Political Science Paper prepared for the Annual Conference of the Political Studies Association, Brighton, Session 6 Executive Politics, Bureaucracy and Legislation Tuesday 22 March 15:30-17:00 . DRAFT. Abstract Like many other things, statutes are shaped by their environments. It is possible to show that a range of constitutional and institutional constraints produce characteristics shared by much legislation in one jurisdiction that distinguish it from much legislation in others. These characteristics include features such as the specificity of the language in which laws are written, how statutes delegate powers, the use of symbolism in legislation and the degree to which policy is developed in a cumulative manner. These features are not matters of “culture” or “style” but rather result from a) the role of statute in the wider legal-administrative system and b) the mode of production of legislation. This argument is developed on the basis of an analysis of 1,150 laws passed in 2014 in Germany, France, the UK, Sweden and the USA. Legislation is arguably the most powerful instrument of government (see Hood 1983). It is the expression of government authority backed up by the state's "monopoly of legitimate force" (Weber 1983). Yet apart from their authoritativeness there is rather little that can be said about the characteristics of laws as tools of government. In fact, each law is unique in what precisely it permits, mandates, authorises and prohibits, and to what ends. In this paper I explore a way of looking at legislation in between these two levels of abstraction: on the one hand law as supreme instrument and on the other laws as the idiosyncratic content of any individual piece of legislation. -

Introduction

Introduction “Therefore I take pleasure in infirmities, inreproaches,innecessities,inpersecu- tions, in distresses for Christ’s sake: for whenIamweak,thenamIstrong”- 2 Corinthians 12:10 The above quotation perfectly describes the female visionary writers discussed in this study, namely women who when confronted with cultural restrictions and negative stereotypes, found a voice of their own against all odds. By using their so-called infirmities, such as weakness and illness and the reproaches against them, they were able to turn these into strengths. Rather than stay- ing silent, these women wrote and published, thereby turning their seeming frailties into powerful texts. The focus of the following investigation revolves around two English visionary writers from the Middle Ages Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe as well as several female prophets such as Anna Trapnel, Anne Wentworth and Katherine Chidley from the seventeenth century. That period, particularly the decades between the 1640s and the 1660s, saw many revolutionary changes. In addition to such significant events as the behead- ing of Charles I in 1649 and the introduction of Cromwell’s Protectorate in 1653, “the extensive liberty of the press in England [...] may have [made it] easier for eccentrics to get into print than ever before or since” (Hill, The World Turned Upside Down 17). Indeed, according to Phyllis Mack, over 300 female vi- sionaries were able to use the absence of censorship at that time to voice their concerns and write about their lives and circumstances in prophetic writings (218). In addition to the absence of censorship the mode of prophecy was often used by these female visionaries in order to voice their concerns and ideas. -

Evolution and Gestalt of the State in the United Kingdom

Martin Loughlin Evolution and Gestalt of the state in the United Kingdom Book section (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Originally published in: Cassese, Sabino, von Bogdandy, Armin and Huber, Peter, (eds.) The Max Planck Handbooks in European Public Law: The Administrative State. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2017 © 2017 Oxford University Press This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/81516/ Available in LSE Research Online: June 2017 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s submitted version of the book section. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Ius Publicum Europaeum: The Max Planck Handbook of European Public Law Vol. I: Public Law and Public Authority § 15: United Kingdom Martin Loughlin Outline 1. INTRODUCTION 2. STATE 2.1. Introduction 2.2. State formation 2.3. The Crown, the Government and the Body Politic 2.4. Crown Prerogatives 3. -

Rump Ballads and Official Propaganda (1660-1663)

Ezra’s Archives | 35 A Rhetorical Convergence: Rump Ballads and Official Propaganda (1660-1663) Benjamin Cohen In October 1917, following the defeat of King Charles I in the English Civil War (1642-1649) and his execution, a series of republican regimes ruled England. In 1653 Oliver Cromwell’s Protectorate regime overthrew the Rump Parliament and governed England until his death in 1659. Cromwell’s regime proved fairly stable during its six year existence despite his ruling largely through the powerful New Model Army. However, the Protectorate’s rapid collapse after Cromwell’s death revealed its limited durability. England experienced a period of prolonged political instability between the collapse of the Protectorate and the restoration of monarchy. Fears of political and social anarchy ultimately brought about the restoration of monarchy under Charles I’s son and heir, Charles II in May 1660. The turmoil began when the Rump Parliament (previously ascendant in 1649-1653) seized power from Oliver Cromwell’s ineffectual son and successor, Richard, in spring 1659. England’s politically powerful army toppled the regime in October, before the Rump returned to power in December 1659. Ultimately, the Rump was once again deposed at the hands of General George Monck in February 1660, beginning a chain of events leading to the Restoration.1 In the following months Monck pragmatically maneuvered England toward a restoration and a political 1 The Rump Parliament refers to the Parliament whose membership was composed of those Parliamentarians that remained following the expulsion of members unwilling to vote in favor of executing Charles I and establishing a commonwealth (republic) in 1649. -

The Canadian Bar Review

THE CANADIAN BAR REVIEW VOL . XXX OCTOBER 1952 NO . 8 The Rule Against the Use of Legislative History: "Canon of Construction or Counsel Of Caution"? D. G . KILGOUR* . Toronto I. Introduction The question whether the rule against the use of legislative his- tory is a "canon of construction or counsel of caution" I is only one', but perhaps the least explored, 2 aspect of the general problem of admissibility of extrinsic evidence in the interpretation of written documents. This general problem, in turn, is only one, but perhaps the most important,3 aspect of interpretation at large, which is a problem of general jurisprudence. In fact, juris- prudence itself has been defined as the art of interpreting laws.4 Interpretation or construction of a statute, as of any written document, is an exercise in the ascertainment of meaning. On principle, therefore; everything which is logically relevant should be admissible. Since a statute is an instrument of government * D. G. Kilgour, B .A. (Tor.), LL.M. (Harv.), of the Ontario Bar . Assist- ant Professor, School of Law, University of Toronto. 1 Per Bowen L. J. in Re Jodrell (1890),, L.R. 44 Ch.D. 590, at p. 614. 2 Lauterpacht, Some Observations on Preparatory Work in the Interpreta- tion of Treaties (1935), 48 Harv. L. Rev. 549, at p. 558. 3 Frankfurter, Some Reflections on the Reading of Statutes (1947), 47 Col. L. Rev. 527, at p. 529 : "I should say that the troublesome phase of construction is the determination of the extent to which extraneous docu- mentation and external circumstances may be allowed to infiltrate the text on, ihé theory that they were part of it, written in ink discernable to the judicial eye" . -

Christmas Is Cancelled! What Were Cromwell’S Main Political and Religious Aims for the Commonwealth 1650- 1660?

The National Archives Education Service Christmas is Cancelled! What were Cromwell’s main political and religious aims for the Commonwealth 1650- 1660? Cromwell standing in State as shown in Cromwelliana Christmas is Cancelled! What were Cromwell’s main political and religious aims? Contents Background 3 Teacher’s notes 4 Curriculum Connections 5 Source List 5 Tasks 6 Source 1 7 Source 2 9 Source 3 10 Source 4 11 Source 5 12 Source 6 13 Source 7 14 Source 8 15 Source 9 16 This resource was produced using documents from the collections of The National Archives. It can be freely modified and reproduced for use in the classroom only. 2 Christmas is Cancelled! What were Cromwell’s main political and religious aims? Background On 30 January 1649 Charles I the King of England was executed. Since 1642 civil war had raged in England, Scotland and Ireland and men on opposite sides (Royalists and Parliamentarians) fought in battles and sieges that claimed the lives of many. Charles I was viewed by some to be the man responsible for the bloodshed and therefore could not be trusted on the throne any longer. A trial resulted in a guilty verdict and he was executed outside Banqueting House in Whitehall. During the wars Oliver Cromwell had risen amongst Army ranks and he led the successful New Model Army which had helped to secure Parliament’s eventual victory. Cromwell also achieved widespread political influence and was a high profile supporter of the trial and execution of the King. After the King’s execution England remained politically instable. -

A Study in Regicide . an Analysis of the Backgrounds and Opinions of the Twenty-Two Survivors of the '

A study in regicide; an analysis of the backgrounds and opinions of the twenty- two survivors of the High court of Justice Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Kalish, Edward Melvyn, 1940- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 14:22:32 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318928 A STUDY IN REGICIDE . AN ANALYSIS OF THE BACKGROUNDS AND OPINIONS OF THE TWENTY-TWO SURVIVORS OF THE ' •: ; ■ HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE >' ' . by ' ' ■ Edward Ho Kalish A Thesis Submittedto the Faculty' of 'the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ' ' In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of : MASTER OF ARTS .In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 6 3 STATEMENT:BY AUTHOR / This thesishas been submitted in partial fulfill ment of requirements for an advanced degree at The - University of Arizona and is deposited in The University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library« Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowedg- ment. of source is madeRequests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department .or the Dean of the Graduate<College-when in their judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship«' ' In aliiotdiefV instanceshowever, permission .