Comedy As a Tool for Social Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sideways Title Page

SIDEWAYS by Alexander Payne & Jim Taylor (Based on the novel by Rex Pickett) May 29, 2003 UNDER THE STUDIO LOGO: KNOCKING at a door and distant dog BARKING. NOW UNDER BLACK, A CARD -- SATURDAY The rapping, at first tentative and polite, grows insistent. Then we hear someone getting out of bed. MILES (O.S.) ...the fuck... A door is opened, and the black gives way to blinding white light, the way one experiences the first glimpse of day amid, say, a hangover. A worker, RAUL, is there. MILES (O.S.) Yeah? RAUL Hi, Miles. Can you move your car, please? MILES (O.S.) What for? RAUL The painters got to put the truck in, and you didn’t park too good. MILES (O.S.) (a sigh, then --) Yeah, hold on. He closes the door with a SLAM. EXT. HIDEOUS APARTMENT COMPLEX - DAY SUPERIMPOSE -- SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA Wearing only underwear, a bathrobe, and clogs, MILES RAYMOND comes out of his unit and heads toward the street. He passes some SIX MEXICANS, ready to work. 2. He climbs into his twelve-year-old convertible SAAB, parked far from the curb and blocking part of the driveway. The car starts fitfully. As he pulls away, the guys begin backing up the truck. EXT. STREET - DAY Miles rounds the corner and finds a new parking spot. INT. CAR - CONTINUOUS He cuts the engine, exhales a long breath and brings his hands to his head in a gesture of headache pain or just plain anguish. He leans back in his seat, closes his eyes, and soon nods off. -

Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation

Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation SCOPE The Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation sector (sector 71) includes a wide range of establish- ments that operate facilities or provide services to meet varied cultural, entertainment, and recre- ational interests of their patrons. This sector comprises (1) establishments that are involved in producing, promoting, or participating in live performances, events, or exhibits intended for pub- lic viewing; (2) establishments that preserve and exhibit objects and sites of historical, cultural, or educational interest; and (3) establishments that operate facilities or provide services that enable patrons to participate in recreational activities or pursue amusement, hobby, and leisure time interests. Some establishments that provide cultural, entertainment, or recreational facilities and services are classified in other sectors. Excluded from this sector are: (1) establishments that provide both accommodations and recreational facilities, such as hunting and fishing camps and resort and casino hotels are classified in Subsector 721, Accommodation; (2) restaurants and night clubs that provide live entertainment, in addition to the sale of food and beverages are classified in Subsec- tor 722, Food Services and Drinking Places; (3) motion picture theaters, libraries and archives, and publishers of newspapers, magazines, books, periodicals, and computer software are classified in Sector 51, Information; and (4) establishments using transportation equipment to provide recre- ational and entertainment services, such as those operating sightseeing buses, dinner cruises, or helicopter rides are classified in Subsector 487, Scenic and Sightseeing Transportation. Data for this sector are shown for establishments of firms subject to federal income tax, and sepa- rately, of firms that are exempt from federal income tax under provisions of the Internal Revenue Code. -

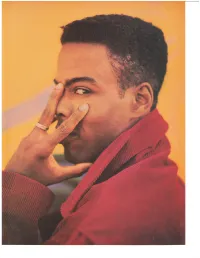

Chris Rock? by Tom 0'Lleill Spot in the Lineup)Than Performing Themundane Task of Pr0motings0me Moviehe's Only Co-Written, Coproduced Andstarred In

ook'$ toll ChrisRock's eyes dart toward the door of hisoffice every time thesound of hiscolleague$ at work 0n the other side nearly knocksit off its hinges. Clearly, he'd rather be ouer there with Adam$andler, David $pade and Chris Farley - theYoung Turks of '$aturdayl{ight [ive' - whippingupa sketch for this week's show (anden$uring his Firstthe comedy clubs, then the almighty 'Saturdayl{ight live' and noltr his otlln movie, nCB4.n Dogood thingscome in threes for Chris Rock? By Tom 0'lleill spot in the lineup)than performing themundane task of pr0motings0me moviehe's only co-written, coproduced andstarred in. Perched notunlike abird about to take flight, the twenty-six-year-old sits onthe heels of hisshoe$, planted $quarely onthe seat of his swivelchair, and turns in measured half-circles. "The pres$ure's 0il,"says Fock of 'C84'(short for "Cell Block 4") the rap c0me- dythat could propel him out of herefaster than you can think tddief$urphy."l||y namens allover this. lf it hits,we got a hit. lf it fails,'Cilristoek'is the only name the audience isgoing t0 krow.nn Photog/aphs by D OMINIQUE PALOMBO US APRIL 1993.69 f Heaps of paper literally falling from his desktop every time he "But no one took me seriously becauseI was too young." brushes against it testify that it's not for lack of trying that this At about the sametime, Grazer met rap pioneer Tone Loc and whisper-thin comedian (five-foot-eleven, 130 pounds) isn't becamefascinated with what he perceivedto be a subculture of akeady a household name. -

George Lopez Show Youtube

George lopez show youtube "What am I gonna tell my mom? She thinks I'm at Epcot!!" Bruh I relate, told my parents I was stayin the. In the hilarious third season of George Lopez, George's life hasn't become Bullock (the show's co. Funny Parts From 2 George Lopez Episodes. This is my show I watch it every morning when I wake up for. George Lopez Season 1 Outtakes. no1banonna. Loading. I miss this show but it is on at 3 in the morning I. George Lopez Why You Crying Show more with all these celebrities dying and even though George isnt. funniest George Lopez quotes ever. your mother, ta loco I enjoyed meeting your mother" DUDE IM DEAD. The Martin Show Bloopers - Duration: JJMAX , views · Lopez Tonight - Interview. belita and george works well together. i tried watching the saint george and that mom he has on there. george lopez full episodes. Show more. Show less. Loading Autoplay When autoplay is enabled, a. SAINT GEORGE premieres MARCH 6th at 9pm on FX! Funniest Comedy Show Best Stand up Comedy Apollo needs to boot Steve Harvey as replace him with George instead!!!. Read more. Show Lopez is so. Vic is hilarious and his relationship with George is the BEST. Enjoy! Copyright The George Lopez Show. All. Mix - Hilarious George Lopez SceneYouTube · George Mesmerizing - Duration: Sarmen 15, George Lopez spanglish very funny lol. Show more. Show less George Lopez one of the best latino. George Lopez S04E14 George Gets Assisterance Part 3 HQ. jeff sa George Lopez Season 4. -

Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2017 On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era Amanda Kay Martin University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Amanda Kay, "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/ Colbert Era. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4759 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Amanda Kay Martin entitled "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Communication and Information. Barbara Kaye, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mark Harmon, Amber Roessner Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Amanda Kay Martin May 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Amanda Kay Martin All rights reserved. -

Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment CURRENT ISSUES in ISLAM

Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment CURRENT ISSUES IN ISLAM Editiorial Board Baderin, Mashood, SOAS, University of London Fadil, Nadia, KU Leuven Goddeeris, Idesbald, KU Leuven Hashemi, Nader, University of Denver Leman, Johan, GCIS, emeritus, KU Leuven Nicaise, Ides, KU Leuven Pang, Ching Lin, University of Antwerp and KU Leuven Platti, Emilio, emeritus, KU Leuven Tayob, Abdulkader, University of Cape Town Stallaert, Christiane, University of Antwerp and KU Leuven Toğuşlu, Erkan, GCIS, KU Leuven Zemni, Sami, Universiteit Gent Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment Settling into Mainstream Culture in the 21st Century Benjamin Nickl Leuven University Press Published with the support of the Popular Culture Association of Australia and New Zealand University of Sydney and KU Leuven Fund for Fair Open Access Published in 2020 by Leuven University Press / Presses Universitaires de Louvain / Universitaire Pers Leuven. Minderbroedersstraat 4, B-3000 Leuven (Belgium). © Benjamin Nickl, 2020 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Non-Derivative 4.0 Licence. The licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non- commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: B. Nickl. 2019. Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment: Settling into Mainstream Culture in the 21st Century. Leuven, Leuven University Press. (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Further details about Creative Commons licences -

BILL COSBY Biography

BILL COSBY Biography Bill Cosby is, by any standards, one of the most influential stars in America today. Whether it be through concert appearances or recordings, television or films, commercials or education, Bill Cosby has the ability to touch people’s lives. His humor often centers on the basic cornerstones of our existence, seeking to provide an insight into our roles as parents, children, family members, and men and women. Without resorting to gimmickry or lowbrow humor, Bill Cosby’s comedy has a point of reference and respect for the trappings and traditions of the great American humorists such as Mark Twain, Buster Keaton and Jonathan Winters. The 1984-92 run of The Cosby Show and his books Fatherhood and Time Flies established new benchmarks on how success is measured. His status at the top of the TVQ survey year after year continues to confirm his appeal as one of the most popular personalities in America. For his philanthropic efforts and positive influence as a performer and author, Cosby was honored with a 1998 Kennedy Center Honors Award. In 2002, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian honor, was the 2009 recipient of the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor and the Marian Anderson Award. The Cosby Show - The 25th Anniversary Commemorative Edition, released by First Look Studios and Carsey-Werner, available in stores or online at www.billcosby.com. The DVD box set of the NBC television hit series is the complete collection of one of the most popular programs in the history of television, garnering 29 Emmy® nominations with six wins, six Golden Globe® nominations with three wins and ten People’s Choice Awards. -

The Runners of Shawnee Road

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Fall 12-20-2013 The Runners of Shawnee Road Melissa Remark University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Remark, Melissa, "The Runners of Shawnee Road" (2013). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1761. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1761 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Runners of Shawnee Road A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Film, Theater and Communication Arts Creative Writing by Melissa Remark B.A. Trent University, 2010 Diploma, Humber College, 2000 December, 2013 The Sheeny Man rides through the streets pulling his wagon of junk. Sometimes he is black, sometimes he is white, and sometimes he is French. -

The Queer" Third Species": Tragicomedy in Contemporary

The Queer “Third Species”: Tragicomedy in Contemporary LGBTQ American Literature and Television A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences by Lindsey Kurz, B.A., M.A. March 2018 Committee Chair: Dr. Beth Ash Committee Members: Dr. Lisa Hogeland, Dr. Deborah Meem Abstract This dissertation focuses on the recent popularity of the tragicomedy as a genre for representing queer lives in late-twentieth and twenty-first century America. I argue that the tragicomedy allows for a nuanced portrayal of queer identity because it recognizes the systemic and personal “tragedies” faced by LGBTQ people (discrimination, inadequate legal protection, familial exile, the AIDS epidemic, et cetera), but also acknowledges that even in struggle, in real life and in art, there is humor and comedy. I contend that the contemporary tragicomedy works to depart from the dominant late-nineteenth and twentieth-century trope of queer people as either tragic figures (sick, suicidal, self-loathing) or comedic relief characters by showing complex characters that experience both tragedy and comedy and are themselves both serious and humorous. Building off Verna A. Foster’s 2004 book The Name and Nature of Tragicomedy, I argue that contemporary examples of the tragicomedy share generic characteristics with tragicomedies from previous eras (most notably the Renaissance and modern period), but have also evolved in important ways to work for queer authors. The contemporary tragicomedy, as used by queer authors, mixes comedy and tragedy throughout the text but ultimately ends in “comedy” (meaning the characters survive the tragedies in the text and are optimistic for the future). -

Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modern Political Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart." Social Research 79.1 (Spring 2012): 1-32

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (Classical Studies) Classical Studies at Penn 2012 Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modernolitical P Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart Ralph M. Rosen University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Rosen, R. M. (2012). Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modernolitical P Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/33 Rosen, Ralph M. "Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modern Political Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart." Social Research 79.1 (Spring 2012): 1-32. http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/social_research/summary/v079/ 79.1.rosen.html Copyright © 2012 The Johns Hopkins University Press. This article first appeared in Social Research: An International Quarterly, Volume 79, Issue 1, Spring, 2012, pages 1-32. Reprinted with permission by The Johns Hopkins University Press. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/33 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modernolitical P Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart Keywords Satire, Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, Jon Stewart Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Classics Comments Rosen, Ralph M. "Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modern Political Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart." Social Research 79.1 (Spring 2012): 1-32. http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/ social_research/summary/v079/79.1.rosen.html Copyright © 2012 The Johns Hopkins University Press. This article first appeared in Social Research: An International Quarterly, Volume 79, Issue 1, Spring, 2012, pages 1-32. -

COMEDY CENTRAL Records(R) to Release George Lopez's 'Tall, Dark & Chicano' CD on Tuesday, December 15

COMEDY CENTRAL Records(R) to Release George Lopez's 'Tall, Dark & Chicano' CD on Tuesday, December 15 NEW YORK, Nov 23, 2009 -- He has his own nightly talk show, a hit comedy series and now this! George Lopez adds another notch to his belt with his new COMEDY CENTRAL Records CD, "Tall, Dark & Chicano" released on Tuesday, December 15. George Lopez's "Tall, Dark & Chicano" CD is a recording of his live stand-up HBO special, where he performed in front of a packed arena crowd at the AT&T Center in San Antonio, TX. One of the most popular comedic actors in the world, Lopez's standup comedy is a sell-out attraction from coast to coast. Well- known as the co-creator, writer, producer, and star of the hit sitcom "George Lopez," Lopez has hosted the Latin Emmy® Awards, co-hosted the Emmys® and now has his own nightly comedy talk show on TBS. He's also a celebrated radio show host in his hometown of Los Angeles, as well as a writer, and comedy recording artist, with CDs and DVDs selling in excess of six figures. Previously released recordings by COMEDY CENTRAL Records include: Greg Giraldo's "Midlife Vices, Nick Swardson's "Seriously, Who Farted?," Doug Benson's "Unbalanced Load," Dane Cook's "ISolated INcident," Cook's platinum-selling "Harmful If Swallowed" and double-platinum "Retaliation," Mitch Hedberg's "Do You Believe in Gosh?," Grammy Award-winning "Lewis Black: The Carnegie Hall Performance," Grammy Award-nominees' Steven Wright's "I Still Have A Pony" and George Lopez's "America's Mexican," Joe Rogan's "Shiny Happy Jihad," Christopher Titus's "5th Annual End Of The World Tour," Norm MacDonald's "Ridiculous," Demetri Martin's "These Are Jokes," "Jim Gaffigan: Beyond The Pale," Mike Birbiglia's "My Secret Public Journal Live," D.L. -

Middle Comedy: Not Only Mythology and Food

Acta Ant. Hung. 56, 2016, 421–433 DOI: 10.1556/068.2016.56.4.2 VIRGINIA MASTELLARI MIDDLE COMEDY: NOT ONLY MYTHOLOGY AND FOOD View metadata, citation and similar papersTHE at core.ac.ukPOLITICAL AND CONTEMPORARY DIMENSION brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of the Academy's Library Summary: The disappearance of the political and contemporary dimension in the production after Aris- tophanes is a false belief that has been shared for a long time, together with the assumption that Middle Comedy – the transitional period between archaia and nea – was only about mythological burlesque and food. The misleading idea has surely risen because of the main source of the comic fragments: Athenaeus, The Learned Banqueters. However, the contemporary and political aspect emerges again in the 4th c. BC in the creations of a small group of dramatists, among whom Timocles, Mnesimachus and Heniochus stand out (significantly, most of them are concentrated in the time of the Macedonian expansion). Firstly Timocles, in whose fragments the personal mockery, the onomasti komodein, is still present and sharp, often against contemporary political leaders (cf. frr. 17, 19, 27 K.–A.). Then, Mnesimachus (Φίλιππος, frr. 7–10 K.–A.) and Heniochus (fr. 5 K.–A.), who show an anti- and a pro-Macedonian attitude, respec- tively. The present paper analyses the use of the political and contemporary element in Middle Comedy and the main differences between the poets named and Aristophanes, trying to sketch the evolution of the genre, the points of contact and the new tendencies. Key words: Middle Comedy, Politics, Onomasti komodein For many years, what is known as the “food fallacy”1 has been widespread among scholars of Comedy.