The Mysterious Loss of the Third Molar in the New World Monkey Family Callitrichidae and Its Relationship to Phyletic Dwarfism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development Team

Paper No. : 14 Human Origin and Evolution Module : 09 Classification and Distribution of Living Primates Development Team Principal Investigator Prof. Anup Kumar Kapoor Department of Anthropology, University of Delhi Dr. Satwanti Kapoor (Retd Professor) Paper Coordinator Department of Anthropology, University of Delhi Mr. Vijit Deepani & Prof. A.K. Kapoor Content Writer Department of Anthropology, University of Delhi Prof. R.K. Pathak Content Reviewer Department of Anthropology, Panjab University, Chandigarh 1 Classification and Distribution of Living Primates Anthropology Description of Module Subject Name Anthropology Paper Name Human Origin and Evolution Module Name/Title Classification and Distribution of Living Primates Module Id 09 Contents: Primates: A brief Outline Classification of Living Primates Distribution of Living Primates Summary Learning Objectives: To understand the classification of living primates. To discern the distribution of living primates. 2 Classification and Distribution of Living Primates Anthropology Primates: A brief Outline Primates reside at the initial stage in the series of evolution of man and therefore constitute the first footstep of man’s origin. Primates are primarily mammals possessing several basic mammalian features such as presence of mammary glands, dense body hair; heterodonty, increased brain size, endothermy, a relatively long gestation period followed by live birth, considerable capacity for learning and behavioural flexibility. St. George J Mivart (1873) defined Primates (as an order) -

Fascinating Primates 3/4/13 8:09 AM Ancient Egyptians Used Traits of an Ibis Or a Hamadryas Used Traits Egyptians Ancient ) to Represent Their God Thoth

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Fascinating Primates Fascinating The Beginning of an Adventure Ever since the time of the fi rst civilizations, nonhuman primates and people have oc- cupied overlapping habitats, and it is easy to imagine how important these fi rst contacts were for our ancestors’ philosophical refl ections. Long ago, adopting a quasi- scientifi c view, some people accordingly regarded pri- mates as transformed humans. Others, by contrast, respected them as distinct be- ings, seen either as bearers of sacred properties or, conversely, as diabolical creatures. A Rapid Tour around the World In Egypt under the pharaohs, science and religion were still incompletely separated. Priests saw the Papio hamadryas living around them as “brother baboons” guarding their temples. In fact, the Egyptian god Thoth was a complex deity combining qualities of monkeys and those of other wild animal species living in rice paddies next to temples, all able to sound the alarm if thieves were skulking nearby. At fi rst, baboons represented a local god in the Nile delta who guarded sacred sites. The associated cult then spread through middle Egypt. Even- tually, this god was assimilated by the Greeks into Hermes Trismegistus, the deity measuring and interpreting time, the messenger of the gods. One conse- quence of this deifi cation was that many animals were mummifi ed after death to honor them. Ancient Egyptians used traits of an ibis or a Hamadryas Baboon (Papio hamadryas) to represent their god Thoth. -

The Survival of the Central American Squirrel Monkey

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2005 The urS vival of the Central American Squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedi): the habitat and behavior of a troop on the Burica Peninsula in a conservation context Liana Burghardt SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, and the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Burghardt, Liana, "The urS vival of the Central American Squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedi): the habitat and behavior of a troop on the Burica Peninsula in a conservation context" (2005). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 435. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/435 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Survival of the Central American Squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedi): the habitat and behavior of a troop on the Burica Peninsula in a conservation context Liana Burghardt Carleton College Fall 2005 Burghardt 2 I dedicate this paper which documents my first scientific adventure in the field to my father. “It is often necessary to put aside the objective measurements favored in controlled laboratory environments and to adopt a more subjective naturalistic viewpoint in order to see pattern and consistency in the rich, varied context of the natural environment” (Baldwin and Baldwin 1971: 48). Acknowledgments This paper has truly been an adventure and as is common I have many people I wish to thank. -

Goeldi's Monkey

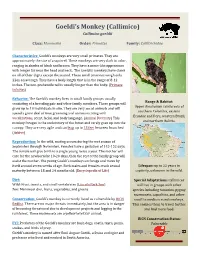

Goeldi’s Monkey (Callimico) Callimico goeldii Class: Mammalia Order: Primates Family: Callitrichidae Characteristics: Goeldi’s monkeys are very small primates. They are approximately the size of a squirrel. These monkeys are very dark in color, ranging in shades of black and brown. They have a mane-like appearance with longer fur near the head and neck. The Goeldi’s monkeys have claws on all of their digits except the second. These small primates weigh only 22oz on average. They have a body length that is in the range of 8-12 inches. The non-prehensile tail is usually longer than the body. (Primate Info Net) Behavior: The Goeldi’s monkey lives in small family groups usually consisting of a breeding pair and other family members. These groups will Range & Habitat: Upper Amazonian rainforests of grow up to 10 individuals in size. They are very social animals and will southern Colombia, eastern spend a great deal of time grooming and communicating with Ecuador and Peru, western Brazil, vocalizations, scent, facial, and body language. (Animal Diversity) This and northern Bolivia. monkey forages in the understory of the forest and rarely goes up into the canopy. They are very agile and can leap up to 13 feet between branches! (Arkive) Reproduction: In the wild, mating occurs during the wet season of September through November. Females have a gestation of 145-152 days. The female will give birth to a single young twice a year. The mother will care for the newborn for 10-20 days, then the rest of the family group will assist the mother. -

World's Most Endangered Primates

Primates in Peril The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018 Edited by Christoph Schwitzer, Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands, Federica Chiozza, Elizabeth A. Williamson, Elizabeth J. Macfie, Janette Wallis and Alison Cotton Illustrations by Stephen D. Nash IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG) International Primatological Society (IPS) Conservation International (CI) Bristol Zoological Society (BZS) Published by: IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), Bristol Zoological Society (BZS) Copyright: ©2017 Conservation International All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Inquiries to the publisher should be directed to the following address: Russell A. Mittermeier, Chair, IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group, Conservation International, 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500, Arlington, VA 22202, USA. Citation (report): Schwitzer, C., Mittermeier, R.A., Rylands, A.B., Chiozza, F., Williamson, E.A., Macfie, E.J., Wallis, J. and Cotton, A. (eds.). 2017. Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), and Bristol Zoological Society, Arlington, VA. 99 pp. Citation (species): Salmona, J., Patel, E.R., Chikhi, L. and Banks, M.A. 2017. Propithecus perrieri (Lavauden, 1931). In: C. Schwitzer, R.A. Mittermeier, A.B. Rylands, F. Chiozza, E.A. Williamson, E.J. Macfie, J. Wallis and A. Cotton (eds.), Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018, pp. 40-43. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), and Bristol Zoological Society, Arlington, VA. -

Habitat Use by Callicebus Coimbrai (Primates: Pitheciidae) and Sympatric Species in the Fragmented Landscape of the Atlantic Forest of Southern Sergipe, Brazil

ZOOLOGIA 27 (6): 853–860, December, 2010 doi: 10.1590/S1984-46702010000600003 Habitat use by Callicebus coimbrai (Primates: Pitheciidae) and sympatric species in the fragmented landscape of the Atlantic Forest of southern Sergipe, Brazil Renata Rocha Déda Chagas1, 3 & Stephen F. Ferrari2 1 Programa de Pós-graduação em Desenvolvimento e Meio Ambiente, Universidade Federal de Sergipe, Avenida Marechal Rondon, Jardim Rosa Elze, 49.100-000 São Cristóvão, SE, Brazil. 2 Departamento de Biologia, Universidade Federal de Sergipe. Avenida Marechal Rondon, Jardim Rosa Elze, 49100-000 São Cristóvão, SE, Brazil. 3 Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Anthropogenic habitat fragmentation is a chronic problem throughout the Brazilian Atlantic Forest biome. In the present study, four forest fragments of 60-120 ha were surveyed on a rural property in southern Sergipe, where two endangered primate species, Callicebus coimbrai Kobayashi & Langguth, 1999 and Cebus xanthosternos Wied-Neuwied, 1826, are found. Two transects were established in each fragment, and the predominant habitat in 50 m sectors was assigned to one of three categories (mature forest, secondary forest and anthropogenic forest). Standard line transect surveys of the resident primate populations – which included a third species, Callitrhix jacchus Linnaeus, 1758 – were conducted, with a total of 476 km walked transect, resulting in 164 primate sightings. At each sighting of a primate, the habitat class was recorded and the height of the individual above the ground was estimated. The analysis indicated a significant (p < 0.05) preference for mature forest in C. xanthosternos which was also observed more frequently in the larger and better preserved fragments. -

Boletín Antártico Chileno, Edición Especial

EL CONTINENTE DONDE EMPIEZA EL FUTURO Índice DIRECTOR Y REPRESENTANTE LEGAL Presentación José Retamales Espinoza 5 Prólogo 7 EDITOR Reiner Canales La relación entre Sudamérica y la Antártica 11 (E-mail: [email protected]) El pasado de la Antártica… ¿una incógnita develada? 13 COMITÉ EDITORIAL Marcelo Leppe Cartes Edgardo Vega Separación de la fauna marina antártica y sudamericana desde una aproximación molecular 21 Marcelo González Elie Poulin, Claudio González-Wevar, Mathias Hüne, Angie Díaz Marcelo Leppe Conexiones geológicas entre Sudamérica y Antártica 27 Francisco Hervé Allamand DIRECCIÓN DE ARTE Pablo Ruiz Teneb Adaptaciones al Medio Antártico y Biorrecursos 33 El interés por esudiar la biodiversidad microbiológica en la Antártica 35 DISEÑO / DIAGRAMACIÓN Jenny M. Blamey Oscar Giordano / Menssage Producciones El capital celular y molecular para vivir a temperaturas bajo cero en aguas antárticas 39 Víctor Bugueño / Menssage Producciones Marcelo González Aravena Las esrategias de las plantas antárticas para sobrevivir en ambientes extremos y su rol como biorrecursos 45 PORTADA Marco A. Molina-Montenegro, Ian S. Acuña-Rodríguez, Jorge Gallardo-Cerda, Rasme Hereme y Crisian Torres-Díaz EL CONTINENTE Arnaldo Gómez / Menssage Producciones DONDE EMPIEZA EL FUTURO Biodiversidad 53 A más de medio siglo IMPRESIÓN de la fundación del Menssage Producciones Las aves marinas de la península Antártica 55 Instituto Antártico Chileno Santiago de Chile Javier A. Arata El desafío de esudiar y comprender la biodiversidad de los mamíferos marinos antárticos 59 Elías Barticevic Cornejo y FOTOGRAFÍA Anelio Aguayo Lobo Óscar Barrientos Bradasic (Eds.) La desconocida vida y diversidad de los invertebrados terresres antárticos 67 Agradecemos a los autores citados en los créditos Daniel González Acuña fotográficos por su aporte en imágenes al regisro Autores Caracterísicas de la fauna que habita los fondos coseros profundos de la Antártica 75 hisórico de la ciencia antártica nacional. -

Capuchins Are the Most Intelligent New World Monkeys – Perhaps As Intelligent As Chimpanzees

Hooded Capuchin Cebus paella cay Capuchin IQ - Capuchins are the most intelligent New World monkeys – perhaps as intelligent as chimpanzees. They are noted for their ability to fashion and use tools. Because of their ability to learn and remember, they were once trained as “organ grinder” monkeys, are often used in movies and have even been trained to assist disabled people with routine tasks around the house. Get a Grip - Hooded capuchins have a semi-prehensile tail that they can use to grip objects. They have opposable thumbs and big toes on their hands and feet further enabling them to easily manipulate objects. They use their prehensile tail to anchor themselves when climbing around in the trees and to keep them from falling when they sleep. Unlike some monkeys with prehensile tails, capuchins cannot hang by their tail alone. Classification The hooded capuchin is also been referred to as the tufted or brown capuchin. Class: Mammalia Order: Primate Family: Cebidae Genus: Cebus Species: paella Subspecies: cay Distribution This species ranges through northern South America, specifically Venezuela, Brazil, Guyana, Suriname and French Guiana. Habitat Canopies of tropical and mountain rainforests. Physical Description • Hooded capuchins are 12-22 inches (30-56 cm) long with a 15-22 inch (38-56 cm) tail. • Adults weigh six to eight pounds (3-4 kg). • Their fur is light to dark brown with a distinctive black cap on the head. • They have semi-prehensile tails. • Hooded capuchins have tufts of hair that form ridges along the side of the top of their head. Diet What Does It Eat? In the wild: Fruit, flowers, leaves, insects, birds, eggs, lizards, and small mammals. -

Stem Members of Platyrrhini Are Distinct from Catarrhines in at Least One Derived Cranial Feature

Journal of Human Evolution 100 (2016) 16e24 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Human Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol Stem members of Platyrrhini are distinct from catarrhines in at least one derived cranial feature * Ethan L. Fulwood a, , Doug M. Boyer a, Richard F. Kay a, b a Department of Evolutionary Anthropology, Duke University, Box 90383, Durham, NC 27708, USA b Division of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708, USA article info abstract Article history: The pterion, on the lateral aspect of the cranium, is where the zygomatic, frontal, sphenoid, squamosal, Received 3 August 2015 and parietal bones approach and contact. The configuration of these bones distinguishes New and Old Accepted 2 August 2016 World anthropoids: most extant platyrrhines exhibit contact between the parietal and zygomatic bones, while all known catarrhines exhibit frontal-alisphenoid contact. However, it is thought that early stem- platyrrhines retained the apparently primitive catarrhine condition. Here we re-evaluate the condition of Keywords: key fossil taxa using mCT (micro-computed tomography) imaging. The single known specimen of New World monkeys Tremacebus and an adult cranium of Antillothrix exhibit the typical platyrrhine condition of parietal- Pterion Homunculus zygomatic contact. The same is true of one specimen of Homunculus, while a second specimen has the ‘ ’ Tremacebus catarrhine condition. When these new data are incorporated into an ancestral state reconstruction, they MicroCT support the conclusion that pterion frontal-alisphenoid contact characterized the last common ancestor of crown anthropoids and that contact between the parietal and zygomatic is a synapomorphy of Platyrrhini. -

Phylogenetic Relationships in the Genus Cheracebus (Callicebinae, Pitheciidae)

Received: 18 December 2019 | Revised: 6 April 2020 | Accepted: 13 April 2020 DOI: 10.1002/ajp.23167 RESEARCH ARTICLE Phylogenetic relationships in the genus Cheracebus (Callicebinae, Pitheciidae) Jeferson Carneiro1,2 | Iracilda Sampaio1,2 | Thaynara Lima2 | José de S. Silva‐Júnior3 | Izeni Farias4 | Tomas Hrbek4 | João Valsecchi5 | Jean Boubli6 | Horacio Schneider1,2 1Genomics and Systems Biology Center, Universidade Federal do Para, Belem, Brazil Abstract 2Instituto de Estudos Costeiros, Universidade Cheracebus is a new genus of New World primate of the family Pitheciidae, subfamily Federal do Para, Campus Universitario de Bragança, Bragança, Para, Brazil Callicebinae. Until recently, Cheracebus was classified as the torquatus species group 3Mammalogy, Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, of the genus Callicebus. The genus Cheracebus has six species: C. lucifer, C. lugens, C. Belem, Para, Brazil regulus, C. medemi, C. torquatus, and C. purinus, which are all endemic to the Amazon 4Laboratory of Evolution and Animal Genetics, Universidade Federal do Amazonas, Manaus, biome. Before the present study, there had been no conclusive interpretation of the Amazonas, Brazil phylogenetic relationships among most of the Cheracebus species. The present study 5Instituto de Desenvolvimento Sustentável Mamirauá, Mamiraua Sustainable tests the monophyly of the genus and investigates the relationships among the Development Reserve, Amazonas, Brazil different Cheracebus species, based on DNA sequencing of 16 mitochondrial and 6 School of Environment and Life Sciences, nuclear markers. The phylogenetic analyses were based on Maximum Likelihood, University of Salford, Salford, UK Bayesian Inference, and multispecies coalescent approaches. The divergence times Correspondence and genetic distances between the Cheracebus taxa were also estimated. The ana- Jeferson Carneiro, Instituto de Estudos Costeiros, Universidade Federal do Para, lyses confirmed the monophyly of the genus and a well‐supported topology, with the Campus Universitario de Bragança, Alameda following arrangement: ((C. -

Taxonomic Status of Callithrix Kuhlii

Primate Conservation 2006 (2): –24 The Taxonomic Status of Wied’s Black-tufted-ear Marmoset, Callithrix kuhlii (Callitrichidae, Primates) Adelmar F. Coimbra-Filho¹, Russell A. Mittermeier ², Anthony B. Rylands³, Sérgio L. Mendes4, M. Cecília M. Kierulff 5, and Luiz Paulo de S. Pinto6 1Rua Artur Araripe 60/901, Gávea, 22451-020 Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 2Conservation International, Washington, DC, USA 3Center for Applied Biodiversity Science, Conservation International, Washington, DC, USA 4 Departamento de Ciências Biológicas – CCHN, Universidade Federal do, Espírito Santo, Espírito Santo, Brazil 5Fundação Parque Zoológico de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil 6 Conservation International do Brasil, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil Abstract: In this paper we provide a description of Wied’s black tufted-ear marmoset, or the Southern Bahian marmoset, Callithrix kuhlii Coimbra-Filho, 1985, from the Atlantic forest of southern Bahia in Brazil. It was first recorded by Prinz Maximilian zu Wied-Neuwied during his travels in 1815–1816. Its validity was questioned by Hershkovitz (1977, Living New World Monkeys [Platyrrhini], Chicago University Press, Chicago), who considered it a hybrid of two closely related marmosets, C. penicillata and C. geoffroyi. Vivo (99, Taxonomia de Callithrix Erxleben 1777 [Callitrichidae, Primates], Fundação Biodiversitas, Belo Hori- zonte), on the other hand, while demonstrating it was not a hybrid, argued that it was merely a dark variant of C. penicillata. We discuss a number of aspects concerning the taxonomic history of the forms penicillata, jordani, and kuhlii and the validity of the form kuhlii, examining the supposition that it may be a hybrid, besides the evidence concerning vocalizations, morphology, pelage, and ecology. -

New Primate Genus from the Miocene of Argentina

New primate genus from the Miocene of Argentina Marcelo F. Tejedor*†, Ada´ n A. Tauber‡, Alfred L. Rosenberger§¶, Carl C. Swisher IIIʈ, and Marı´aE. Palacios** *Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Cientı´ficasy Te´cnicas, Laboratorio de Investigaciones en Evolucio´n y Biodiversidad, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales, Sede Esquel, Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia ‘‘San Juan Bosco,’’ Sarmiento 849, 9200 Esquel, Argentina; ‡Facultad de Ciencias Exactas, Fı´sicasy Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Co´rdoba, Avenida Velez Sarsfield 249, 5000 Co´rdoba, Argentina; §Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, Brooklyn College, City University of New York, 2900 Bedford Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11210; ¶Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Mammalogy), American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 11024; ʈDepartment of Geological Sciences, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ 08854; and **Museo Regional Provincial ‘‘Padre Manuel Jesu´s Molina,’’ Ramo´n y Cajal 51, 9400 Rı´oGallegos, Argentina Edited by Jeremy A. Sabloff, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, PA, and approved December 28, 2005 (received for review August 4, 2005) Killikaike blakei is a new genus and species of anthropoid from the of the estuary of the Rio Gallegos river. The stratigraphy is late Early Miocene of southeastern Argentina based on the most divided into two members (6): Estancia La Costa (120 m thick pristine fossil platyrrhine skull and dentition known so far. It is part with 18 fossiliferous levels) and Estancia Angelina (103 m thick of the New World platyrrhine clade (Family Cebidae; Subfamily with four fossiliferous levels). There are two types of volcanic ash Cebinae) including modern squirrel (Saimiri) and capuchin mon- at the locality.