It Is the Blues It Is the Blues/Crawling Over Evening for a Feast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TN Bluesletter Week 10 080310.Cdr

(About the Blues continued) offered rich, more complex guitar parts, the beginnings of a blues trend towards separating lead guitar from rhythm playing. Shows begin at 6:30 unless noted Texas acoustic blues relied more on the use of slide, In case of inclement weather, shows will be held just down the and artists like Lightnin' Hopkins and Blind Willie street at the Grand Theater, 102 West Grand Avenue. Johnson are considered masters of slide guitar. Other June 1 Left Wing Bourbon local and regional blues scenes - from New Orleans MySpace.com/LeftWingBourbon June 8 The Pumps to Atlanta, from St. Louis to Detroit - also left their mark ThePumpsBand.com on the acoustic blues sound. MySpace.com/ThePumpsBand When African-American musical tastes began to June 15 The Blues Dogs change in the early-1960s, moving towards soul and August 3, 2010 at Owen Park MySpace.com/SteveMeyerAndTheBluesDogs rhythm & blues music, country blues found renewed June 22 Pete Neuman and the Real Deal popularity as the "folk blues" and was sold to a PeteNeuman.com June 29 Code Blue with Catya & Sue primarily white, college-age audience. Traditional YYoouunngg BBlluueess NNiigghhtt Catya.net artists like Big Bill Broonzy and Sonny Boy Williamson July 6 Mojo Lemon reinvented themselves as folk blues artists, while MojoLemon.com Piedmont bluesmen like Sonny Terry and Brownie MySpace.com/MojoLemonBluesBand McGhee found great success on the folk festival July 13 Dave Lambert DaveLambertBand.com circuit. The influence of original acoustic country July 20 Deep Water Reunion blues can be heard today in the work of MySpace.com/DWReunion contemporary blues artists like Taj Mahal, Cephas & July 27 The Nitecaps Wiggins, Keb' Mo', and Alvin Youngblood Hart. -

Memphis Jug Baimi

94, Puller Road, B L U E S Barnet, Herts., EN5 4HD, ~ L I N K U.K. Subscriptions £1.50 for six ( 54 sea mail, 58 air mail). Overseas International Money Orders only please or if by personal cheque please add an extra 50p to cover bank clearance charges. Editorial staff: Mike Black, John Stiff. Frank Sidebottom and Alan Balfour. Issue 2 — October/November 1973. Particular thanks to Valerie Wilmer (photos) and Dave Godby (special artwork). National Giro— 32 733 4002 Cover Photo> Memphis Minnie ( ^ ) Blues-Link 1973 editorial In this short editorial all I have space to mention is that we now have a Giro account and overseas readers may find it easier and cheaper to subscribe this way. Apologies to Kees van Wijngaarden whose name we left off “ The Dutch Blues Scene” in No. 1—red faces all round! Those of you who are still waiting for replies to letters — bear with us as yours truly (Mike) has had a spell in hospital and it’s taking time to get the backlog down. Next issue will be a bumper one for Christmas. CONTENTS PAGE Memphis Shakedown — Chris Smith 4 Leicester Blues Em pire — John Stretton & Bob Fisher 20 Obscure LP’ s— Frank Sidebottom 41 Kokomo Arnold — Leon Terjanian 27 Ragtime In The British Museum — Roger Millington 33 Memphis Minnie Dies in Memphis — Steve LaVere 31 Talkabout — Bob Groom 19 Sidetrackin’ — Frank Sidebottom 26 Book Review 40 Record Reviews 39 Contact Ads 42 £ Memphis Shakedown- The Memphis Jug Band On Record by Chris Smith Much has been written about the members of the Memphis Jug Band, notably by Bengt Olsson in Memphis Blues (Studio Vista 1970); surprisingly little, however has got into print about the music that the band played, beyond general outline. -

Gayle Dean Wardlow Bibliography

Gayle Dean Wardlow Bibliography -Wardlow, Gayle Dean. Really! The Country Blues. USA: Origin Jazz Library OJL-2, c1962. -Klatzko, Bernard; Wardlow, Gayle Dean. The Immortal Charlie Patton, 1887–1934. Number 2: 1929– 34. USA: Origin Jazz Library OJL-7, 1964. Reprinted in Chasin’ That Devil Music, by Gayle Dean Wardlow, pp. 18–33. San Francisco: Miller Freeman, 1998. Reprinted as notes with Screamin’ and Hollerin’ the Blues: The Worlds of Charley Patton. USA: Revenant 212, 2001. -Wardlow, Gayle Dean. Country Blues Encores. USA: Origin OJL-8, c1965. -Wardlow, Gayle Dean. “Mysteries in Mississippi.” Blues Unlimited no. 30 (Feb 1966): 10. Reprinted in Chasin’ That Devil Music, pp. 110–111. San Francisco: Miller Freeman, 1998. -Wardlow, Gayle Dean. “Legends of the Lost. Pt. 1.” Blues Unlimited no. 31 (Mar 1966): 3–4; “Pt. 2.” Blues Unlimited no. 34 (Jul 1966): 3; “Pt. 3.” Blues Unlimited no. 35 (Aug 1966): 3; “Pt. 4.” Blues Unlimited no. 36 (Sep 1966): 7. Reprinted in Back Woods Blues, ed. S.A. Napier, pp. 25–28. Oxford: Blues Unlimited, 1968. Reprinted in Chasin’ That Devil Music, pp. 126–130. San Francisco: Miller Freeman, 1998. -Wardlow, Gayle Dean; Evans, David. The Mississippi Blues, 1927–1940. USA: Origin OJL-5, 1966. -Wardlow, Gayle Dean. “Son House (Collectors Classics, 14: Comments and Additions).” Blues Unlimited no. 42 (Mar/Apr 1967): 7–8. -Wardlow, Gayle Dean; Roche, Jacques. “Patton’s Murder: Whitewash? or Hogwash?” 78 Quarterly no. 1 (Autumn 1967): 10–17. Reprinted in Chasin’ That Devil Music, pp. 94–100. San Francisco: Miller Freeman, 1998. -Wardlow, Gayle Dean. “King Solomon Hill.” 78 Quarterly no. -

Finding Aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection (MUM00682)

University of Mississippi eGrove Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids Library November 2020 Finding Aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection (MUM00682) Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/finding_aids Recommended Citation Sheldon Harris Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Mississippi Libraries Finding aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection MUM00682 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY INFORMATION Summary Information Repository University of Mississippi Libraries Biographical Note Creator Scope and Content Note Harris, Sheldon Arrangement Title Administrative Information Sheldon Harris Collection Related Materials Date [inclusive] Controlled Access Headings circa 1834-1998 Collection Inventory Extent Series I. 78s 49.21 Linear feet Series II. Sheet Music General Physical Description note Series III. Photographs 71 boxes (49.21 linear feet) Series IV. Research Files Location: Blues Mixed materials [Boxes] 1-71 Abstract: Collection of recordings, sheet music, photographs and research materials gathered through Sheldon Harris' person collecting and research. Prefered Citation Sheldon Harris Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi Return to Table of Contents » BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Born in Cleveland, Ohio, Sheldon Harris was raised and educated in New York City. His interest in jazz and blues began as a record collector in the 1930s. As an after-hours interest, he attended extended jazz and blues history and appreciation classes during the late 1940s at New York University and the New School for Social Research, New York, under the direction of the late Dr. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Dan Hicks’ Caucasian Hip-Hop for Hicksters Published February 19, 2015 | Copyright @2015 Straight Ahead Media

Dan Hicks’ Caucasian Hip-Hop For Hicksters Published February 19, 2015 | Copyright @2015 Straight Ahead Media Author: Steve Roby Showdate : Feb. 18, 2015 Performance Venue : Yoshi’s Oakland Bay Area legend Dan Hicks performed to a sold-out crowd at Yoshi’s on Wednesday. The audience was made up of his loyal fans (Hicksters) who probably first heard his music on KSAN, Jive 95, back in 1969. At age 11, Hicks started out as a drummer, and was heavily influenced by jazz and Dixieland music, often playing dances at the VFW. During the folk revival of the ‘60s, he picked up a guitar, and would go to hootenannies while attending San Francisco State. Hicks began writing songs, an eclectic mix of Western swing, folk, jazz, and blues, and eventually formed Dan Hicks and his Hot Licks. His offbeat humor filtered its way into his stage act. Today, with tongue firmly planted in cheek, Hicks sums up his special genre as “Caucasian hip-hop.” Over four decades later, Hicks still delivers a unique performance, and Wednesday’s show was jammed with many great moments. One of the evenings highlights was the classic “I Scare Myself,” which Hicks is still unclear if it’s a love song when he wrote it back in 1969. “I was either in love, or I’d just eaten a big hashish brownie,” recalled Hicks. Adding to the song’s paranoia theme, back-up singers Daria and Roberta Donnay dawned dark shades while Benito Cortez played a chilling violin solo complete with creepy horror movie sound effects. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Fréhel and Bessie Smith

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 9-18-2018 Fréhel and Bessie Smith: A Cross-Cultural Study of the French Realist Singer and the African American Classic Blues Singer Tiffany Renée Jackson University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Jackson, Tiffany Renée, "Fréhel and Bessie Smith: A Cross-Cultural Study of the French Realist Singer and the African American Classic Blues Singer" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1946. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1946 Fréhel and Bessie Smith: A Cross-Cultural Study of the French Realist Singer and the African American Classic Blues Singer Tiffany Renée Jackson, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 ABSTRACT In this dissertation I explore parallels between the lives and careers of the chan- son réaliste singer Fréhel (1891-1951), born Marguerite Boulc’h, and the classic blues singer Bessie Smith (1894-1937), and between the genres in which they worked. Both were tragic figures, whose struggles with love, abuse, and abandonment culminated in untimely ends that nevertheless did not overshadow their historical relevance. Drawing on literature in cultural studies and sociology that deals with feminism, race, and class, I compare the the two women’s formative environments and their subsequent biographi- cal histories, their career trajectories, the societal hierarchies from which they emerged, and, finally, their significance for developments in women’s autonomy in wider society. Chanson réaliste (realist song) was a French popular song category developed in the Parisian cabaret of the1880s and which attained its peak of wide dissemination and popularity from the 1920s through the 1940s. -

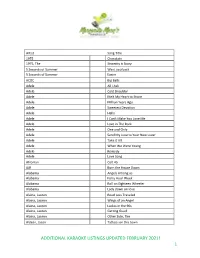

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

The Impact of the Music of the Harlem Renaissance on Society

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1989 Volume I: American Communities, 1880-1980 The Impact of the Music of the Harlem Renaissance on Society Curriculum Unit 89.01.05 by Kenneth B. Hilliard The community of Harlem is one which is rich in history and culture. Throughout its development it has seen everything from poverty to urban growth. In spite of this the people of this community banded together to establish a strong community that became the model for other black urban areas. As a result of this millions have migrated to this community since the 1880’s, bringing with them heritages and traditions of their own. One of these traditions was that of music, and it was through music that many flocked to Harlem, especially in the 1920’s through 1950’s to seek their fortune in the big apple. Somewhere around the year 1918 this melting pot of southern blacks deeply rooted in the traditions of spirituals and blues mixed with the more educated northern blacks to create an atmosphere of artistic and intellectual growth never before seen or heard in America. Here was the birth of the Harlem Renaissance. The purpose of this unit will be to; a. Define the community of Harlem. b. Explain the growth of music in this area. c. Identify important people who spearheaded this movement. d. Identify places where music grew in Harlem. e. Establish a visual as well as an aural account of the musical history of this era. f. Anthologize the music of this era up to and including today’s urban music. -

CONSTRUCTING TIN PAN ALLEY 17 M01 GARO3788 05 SE C01.Qxd 5/26/10 4:35 PM Page 18

M01_GARO3788_05_SE_C01.qxd 5/26/10 4:35 PM Page 15 Constructing Tin Pan 1 Alley: From Minstrelsy to Mass Culture The institution of slavery has been such a defining feature of U.S. history that it is hardly surprising to find the roots of our popular music embedded in this tortured legacy. Indeed, the first indige- nous U.S. popular music to capture the imagination of a broad public, at home and abroad, was blackface minstrelsy, a cultural form involving mostly Northern whites in blackened faces, parodying their perceptions of African American culture. Minstrelsy appeared at a time when songwriting and music publishing were dispersed throughout the country and sound record- The institution of slavery has been ing had not yet been invented. During this period, there was an such a defining feature of U.S. history that it is hardly surprising to find the important geographical pattern in the way music circulated. Concert roots of our popular music embedded music by foreign composers intended for elite U.S. audiences gener- in this tortured legacy. ally played in New York City first and then in other major cities. In contrast, domestic popular music, including minstrel music, was first tested in smaller towns, then went to larger urban areas, and entered New York only after success elsewhere. Songwriting and music publishing were similarly dispersed. New York did not become the nerve center for indigenous popular music until later in the nineteenth century, when the pre- viously scattered conglomeration of songwriters and publishers began to converge on the Broadway and 28th Street section of the city, in an area that came to be called Tin Pan Alley after the tinny output of its upright pianos. -

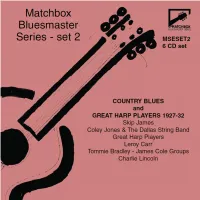

Dallas String Band with Coley Jones: Three Unknowns, Vcl; Acc

MATCHBOX BLUESMASTER SERIES: SET 1: MSESET1 (6 albums) MSE 201 COUNTRY BLUES – THE 1st GENERATION (1927) Series Editor: Johnny Parth MSE 202 BUDDY BOY HAWKINS (1927-29) Notes: Paul Oliver MSE 203 BO WEAVIL JACKSON (1926) Produced by: Gef Lucena MSE 204 RAGTlME BLUES GUITAR (1928-30) Remastering from 78s: Hans Klement, Austrophon Studios, Vienna MSE 205 PEG LEG HOWELL (1928-29) MSE 206 TEXAS ALEXANDER VOL. 1 (1927-28) Digitising from vinyl: Norman White MATCHBOX BLUESMASTER SERIES: SET 3: MSESET3 (6 albums) MSE 213 MEMPHIS HARMONICA KINGS (1929-30) Original recordings from the collections of MSE 214 TEXAS ALEXANDER VOL. 2 (1928-29) Werner Benecke, Joe Bussard, Johnny Parth, Guido van Rijn, MSE 215 RAMBLIN' THOMAS (1928-32) MSE 216 COUNTRY GIRLS (1926-29) Bernd Kuefferle, Hans Maitner MSE 217 RUFUS & BEN QUILLIAN (1929-31) MSE 218 DE FORD BAILEY & BERT BILBRO (1927-31) With thanks to Mark Jones of Bristol Folk Publications for the loan of MATCHBOX BLUESMASTER SERIES: SET 4: MSESET4 (6 albums) MSE 219 JULIUS DANIELS – LIL McCLlNTOCK (1927-30) vinyl LP copies of the original re-issue series MSE 220 TEXAS ALEXANDER VOL. 3 (1929-30) MSE 221 PEG LEG HOWELL (1926-27) Sleeve Design: Bob Doling/Genny Lucena MSE 222 SANCTIFIED JUG BANDS (1928-30) MSE 223 ST. LOUIS BESSlE (1927-30) MSE 224 TEXAS ALEXANDER VOL. 4 (1934-50) Discographical details from Blues and Gospel Records 1902-1942 MATCHBOX BLUESMASTER SERIES: SET 5: MSESET5 (6 albums) by John Godrich and Robert Dixon MSE 1001 BLIND LEMON JEFFERSON (1926-29) MSE 1002 FRANK STOKES (1927-29) Considering the extreme rarity of the original 78s, condition is generally MSE 1003 BLIND BLAKE (1926-29) MSE 1004 BIG BILL BROONZY (1927-32) better than might be expected, but it must be borne in mind that only MSE 1005 MISSISSIPPI SHEIKS VOL.