'Ise 9-Funtsvicte J-Cistorlcac Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Huntsville Quarterly of L O C a L a Rchitecture a N D P Reservation

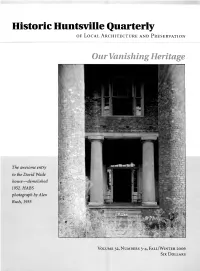

Historic Huntsville Quarterly of L o c a l A rchitecture a n d P reservation Our Vanishing Heritage The awesome entry to the David Wade house— demolished 1952. HABS photograph by Alex Bush, 1935 V o l u m e 32, N u m b e r s 3 -4 , F a l l /W i n t e r 2006 Six D o l l a r s Historic Huntsville Quarterly o f L o c a l A rchitecture a n d P reservation Volum e 32, Num bers 3-4, Fall/W inter 2006 Contents 3 A Tradition of Research and Preservation The Elusive Past D ia n e E l l is From the Beginning L y n n J o n e s 10 Our Vanishing Heritage L in d a B a y e r A l l e n 20 The Second Madison County Courthouse Pa t r ic ia H . R y a n 28 The Horton-McCracken House L in d a B a y e r A l l e n 38 The David Wade House L in d a B a y e r A l l e n 46 The Burritt House P a t r ic ia H . R yan 54 The Demolition Continues T h e Q u a r t e r l y E d it o r s ISSN 1 0 74 -5 6 7X 2 | Our Vanishing Heritage Contributors and Editors Linda Bayer Allen has been researching and writing about Huntsville’s architectur al past intermittently for thirty years. -

City of Huntsville, Alabama Table of Contents

CITY OF HUNTSVILLE, ALABAMA COMMUNITY INFORMATION Prepared for Relocating US Military/Government Personnel and Contractors Office of the Mayor City of Huntsville, Alabama Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………… i Community Overview……………………………………………………………………………… ii Section 1 – City of Huntsville Economy City of Huntsville Economic Quick Facts………………………………………………………….. 1-1 I. General Overview…………………………………………………………………………… 1-3 II. Impact of Redstone Arsenal Activities on Local Economy………………………………… 1-3 III. Economic Diversity……………………………………………………….………………… 1-4 IV. Workforce Profile………..………………………………………………………………….. 1-6 V. Cost of Living……………..………………………………………………………………… 1-11 VI. Financial Outlook of Local Economy………………………………………………………. 1-13 VII. Current Economic Development Initiatives………………………………………………… 1-14 Section 2 – City of Huntsville Housing Characteristics and Availability City of Huntsville Housing Characteristics and Availability Quick Facts………………………….. 2-1 I. General Overview…………………………………………………………………………… 2-3 II. On-Post Housing…………….…………………………….………………………………… 2-3 III. Huntsville Area Housing….……………………………………………….………………… 2-3 IV. Retirement Housing …..…………………………………..………..……………………….. 2-5 Section 3 – City of Huntsville Infrastructure and Environment City of Huntsville Infrastructure and Environment Quick Facts……………………………………. 3-1 I. General Overview………………………………….………………………………………… 3-3 II. Transportation …………………………………….……….………………………………… 3-3 III. Airport Facilities……………..…..……………….……………………….………………… 3-10 IV. Other Infrastructure…..………………………….………..………..………………………. -

The Jackson County Chronicles

ISSN-1071-2348 January 2018 The Jackson County Chronicles Volume 30, Number 1 In this issue: Please renew your membership in the JCHA: Our renewals are • A Tribute to John Neely: A trickling in very slowly this year. If your mailing label identifies you as seminal figure in restoring the Please Renew (meaning you were active in 2017) or Expired Scottsboro freight depot is (meaning you’ve not been active since 2016), please renew for 2018 or remembered in this tribute by convert to a life membership. David Campbell. • Sand Mountain Pottery: Once Our January Meeting: This quarter’s JCHA meeting will feature considered purely utilitarian, two of our favorite folks: Joyce Money Kennamer and JCHA board pottery produced on Sand member Judge John Graham. Joyce will speak about “The Rise and Mountain is now being recognized Decline of Skyline Colony,” and John for its uniqueness and artistry. will talk about the time in 1998 when • A profile of Thomas Jefferson the bulldozers were ready to level Bouldin: Our centennial tribute to historic Skyline School. This our county’s WWI veterans continues. presentation was originally made to a • Clarence Bloomfield Moore : In group at the Skyline Heritage 1914 and 1915, Clarence Association dinner last April. The Bloomfield Moore, the son of a meeting will be held on Sunday, wealthy Philadelphia family, January 28, 2018 at 2:00 p.m. at piloted his boat The Gopher along the Scottsboro Depot Museum. the Tennessee River unearthing native American artifacts. Thanks to our guest contributors in this issue: Blake Wilhelm, • A rail trip through Jackson archivist at Northeast Alabama Community College (NACC); Dr. -

Decadent Dessert Artistry Great Ride

Color, style & kindness • Celebrating Madison • around town MADISON$ LIvINg January 2019 | 4.95 madisonlivingmagazine.com 2018 WEDDINGS MEET 8 MADISON COUPLES DECADENT DESSERT ARTISTRY DESSERT FORK OPENS IN MADISON GREAT RIDE GEORGE BENNETT RETIRES FROM COACHING 3 Easy Ways to Sell Tr a d i t i o n a l S a l e G u a r a n t e e d S a l e In s t a n t O f f e r 256.333.MOVE www.MattCurtisRealEstate.com FrOM the... eDItOr MADISON LIVING EDITORIAL Rebekah Martin Alison James Kendyl Hollingsworth January is always a month of new CONTRIBUTORS beginnings. The year has just begun, Bill Aycock and the challenge of New Year’s Joshua Berry resolutions is at the forefront of our Mayor Paul Finley J Bob Labbe minds. With wedding season quickly Lee Marshall approaching, it is also the start of Jenny Mitschelen something new for many couples in Gregg Parker Madison and Madison County. Joanna Thompson Robert Parker In this issue of Madison Living we Stephanie Robertson will be sharing the wedding days of several local newlyweds. Each couple MARKETING will share their new beginning and the Tori Waits details that made their big day special. ADMINISTRATIVE In addition to the bridal section, the Sierra Jackson Daniel Holmes pages of Madison Living January feature the home of Tony and Cindy ••• Sensenberger on Front Street, the CONTACT US nearly 50-year career of Madison Madison Publications, LLC Academy’s Coach George Bennett and 14 Main St., Suite C P.O. Box 859 Madison’s newest artisan bakery, The Madison, AL 35758 Dessert Fork. -

Historic Huntsville Quarterly O F L O C a L a Rchitecture a N D P Reservation

Historic Huntsville Quarterly o f L o c a l A rchitecture a n d P reservation 19th-Century Dependencies The brick wall o f an old sm okehouse on Adams Street becomes an abstract canvas for the 21st century. Photograph by Doug Brewster V o l u m e 32, N u m b e r s 1-2 , S p r i n g /S u m m e r 2006 S i x D o l l a r s Historic Huntsville Quarterly o f L o c a l A rchitecture a n d P reservation V o l u m e 32 , Num bers 1-2, Spring/Sum m er 2006 Contents 19th-Century Dependencies 3 An Overview L in d a B a y e r A llen 22 Thomas Bibb: Town and Country Pa t r ic ia H . R ya n 33 Northeast Huntsville Neighbors: The Chapman-Johnson and Robinson-Jones Houses D ia n e E ll is 44 The Lewis-Clay House Ly n n Jo n e s 50 The Cox-White House Ly n n [o n e s 56 The McCrary-Thomas House Ly n n Jo n e s ISSN 1074-567X 2 | 19th-Century Dependencies Contributors and Editors Linda Bayer Allen has been researching and writing about Huntsville’s architectur al past intermittently for thirty years. She served as editor of the Historic Huntsville Quarterly for five years and is a member of the present editorial committee. She is retired from the City of Huntsville Planning Department. -

Alabama Center for the Arts

2 Arts Huntsville To Our Education Partners, Arts Huntsville is proud to launch the North Alabama Arts Education Collaborative, an Alabama Artistic Literacy Consortium Initiative. The Arts Education Collaborative is made possible with support from the Alabama State Council on the Arts through funding from the Alabama State Legislature. At Arts Huntsville, our arts education resources and programming will now be directed to the goals and objectives of the North Alabama Arts Education Collaborative to strengthen and support students across the region. Our 2018-19 Arts Education Resource Guide includes the materials you have come to know and expect each year, but in a slightly new and improved format. Once again you will find information about local arts and cultural organizations that have programs available for children in grades preK-12. These programs include a wide variety of classes, lectures, in-school performances, field trips and more. Now, however, they are divided into Arts Integration, Arts Enhancement, Arts Exposure, Arts in the Community and Competition opportunities for your students or children. As champions of STEAM (science, technology, engineering, art and math), we hope this guide enables you to incorporate the arts into your classroom and across the curriculum, while also introducing your students to the abundance of creativity and culture available in Madison and Limestone Counties and the Decatur City area. If we can be of further assistance in the connecting you with these resources, please call the North Alabama Arts Education Collaborative at Arts Huntsville at (256) 519-2787 or explore our website at www.artshuntsville.org. Allison Dillon Jauken Arts Huntsville Executive Director 3 North Alabama Arts Education Collaborative Dear Education Partners, The North Alabama Arts Education Collaborative is one of three new Regional Arts Education Collaborative Centers in Alabama. -

North AL VG 2019 C26f2374-338D-4C67-8345-404Bde016605.Pdf

02 North Alabama Regional Map 04 All Things Fun Region 1 10 All Things Fun Region 2 15 All Things Fun Region 3 18 All Things Fun Region 4 0222 Tee It Up 24 Fishing, Hunting, Boating 26 Festivals 32 Shopping 33 Dining 36 Marinas, Resorts, Cabins, Camping 36 Recreational Vehicles 38 Bed & Breakfasts 39 Lodging 43 Professional Fun Planners Cover photo: U. S. Space & Rocket Center, Huntsville; back cover photo: DeSoto Falls, near Mentone in DeSoto State Park. 31 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 To Lawrenceburg TENNESSEE State Welcome To Nashville To Fayetteville 24 Center A Lexington 118 A 17 64 Ardmore 43 231 MADISON 157 8 r Bridgeport 20 e To Chattanooga v 365 i 251 53 11 99 R 431 LAUDERDALE 361 New Market k 72 Waterloo l 71 Florence E Elkmont B 207 65 79 2 189 B 14 10 7 133 101 LIMESTONE Meridianville PICKWICK Stevenson To Atlanta 16 65 To Memphis LAKE Riverton Killen WILSON Rogersville Alabama Veterans Rose Trail W. C. Handy Museum LAKE 72 Museum & Archives 354 REGION 2 C Iuka JACKSON 71 C 6 48 Normal 83 Joe Wheeler 33 Flat Rock State Park 33 17 Sheffield 351 72 157 72 Cherokee 184 B 45 Hollywood Helen Keller Home, ig 150 D Monte Sano 65 D Natchez Trace Parkway N Athens y 117 a Natchez Trace Museum and Gardens a WHEELER 24 Brownsboro State Muscle n State Park w c LAKE k Welcome Center r Leighton e 31 Unclaimed Ider Welcome a Shoals P C Madison 347 Center Pisgah . -

2014-2015 Guide

2014-2015 GUIDE A PUBLICATION OF THE CHAMBER OF COMMERCE OF HUNTSVILLE/MADISON COUNTY AL-06088149-01 2014-2015 Guide To table of contents HUNTSVILLE Madison County, Alabama Chamber Staff. Published by 4 Alabama Media Group Editorial and advertising offices located at Letter from the Chairman of the Board. .5 200 Westside Square, Suite 100 Huntsville, AL 35801 Chamber Executive Committee. 6 DIRECTOR, AUDIENCE SOLUTIONS Jane Katona [email protected] Chamber Board of Directors. .8 PUBLICATION DIRECTOR Carl Bates [email protected] Economic Development. 11 MANAGING EDITOR Terry Schrimscher Huntsville Arts. 18 ART DIRECTORS Elizabeth Chick Huntsville/Madison County Schools . Patricia Lay 22 PRODUCTION Don Taylor Huntsville/Madison County by the Numbers. .26 [email protected] 2014-2015 Annual Guide to Huntsville/ Huntsville/Madison County Public Services. 28 Madison County, Alabama, is published by Alabama Media Group for the Chamber of Commerce of Huntsville/Madison County Huntsville/Madison County Parks . 37 For membership information, contact: Chamber of Commerce of Business in Huntsville/Madison County. Huntsville/Madison County 41 225 Church Street Huntsville, AL 35801 256.535.2000 phone Huntsville/Madison County Real Estate. .56 256.535.2015 fax www.hsvchamber.org For more information about this 10 Things To Do in Huntsville/Madison County. .60 publication, call 205.325.2237. Alabama Media Group also produces area guides, magazines and other Revitalization. specialty publications. 68 Copyright©2014 Alabama Media Group. All rights reserved. Reproduction -

Make Your Memories in Appalachia's Southern Foothills

Make Your Memories in Appalachia’s Southern Foothills North Alabama marks the southern foothills of the Appalachian Mountain Range, with rocky peaks boldly cut by the rushing waters of the Tennessee River. It is a region of unsurpassed beauty and is renowned for its wooded bluffs and serene nature areas. North Alabama boasts of many assets of interest to the engaged couple -- beautiful landscapes, sparkling lakes, abundant flora and fauna, internationally-acclaimed music and food facilities, a compelling selection of historic sites, and a vibrant array of unexpected destinations. This guide will help you select your dream wedding location from dozens of stunning settings across North Alabama! We look forward to providing you with an exciting adventure. Desoto Falls, Fort Payne, Ala. Cover photo at Oakville Indian Mounds, Danville, Alabama INDEX Stunning Wedding Venues Alabama Music Hall of Fame ........................................................................................................03 Avalon Social..................................................................................................................................04 Burns Bluff at High Falls ................................................................................................................05 Burritt on the Mountain .................................................................................................................06 Delano Park ....................................................................................................................................07 -

Descendants of Thomas Mccrary, * (Scots-Irish Immigrant Ancestor)

Descendants of Thomas McCRARY, * (Scots-Irish Immigrant Ancestor) First Generation 1. Thomas McCRARY, * (Scots-Irish Immigrant Ancestor), son of John (Or James) McCRARY, * [Our Scottish Immigrant Ancestor] and Martha , (Supposition), was born about 1737 in Perhaps Ulster, Northern Ireland, died about 1793 in Duncan's Creek, Laurens Co., South Carolina at age 56, and was buried in Duncan's Creek Presbyterian Church. General Notes: From the cousins' book "From Whence we Came": Our Thomas McCrary was born in Ireland of Scots-Irish parents. There are no known confirmed records of his parents, the date of his birth nor any details of his life in Erin. He arrived in American about 1750, this according to tradition and not a known fact. There were ports of entry in Baltimore and Philadelphia and many immigrants from Northern Ireland arrived at either one of these places. Tradition tells us he came with his brothers, Andrew, John and Robert. According to cousins who have researched the family, there is evidence (but no documentary proof) that they settled for a short time in Pennsylvanis, in the area of York (then Baltimore) Co., and in Lancaster Co. According to the researchers they were many McCrary's (of various spellings) in that area as early as 1730 through 1740's. "Surviving Early Records of York Count, Pennsylvania, 1749-84", in the South Central Genealogical Society, contains an entry (#70), which lists Andrew, John, Robert and Thomas McCrary. But is this our Thomas? Some researchers believe their parents were John and Martha McCrary who lived in Berkeley Co. now Laurens Co., SC, in the Duncan Creek area at the same time as the four brothers. -

Huntsville, Alabama

Official Group Tour Guide for the Huntsville/Madison County Hello Convention & Visitors Bureau HUNTSVILLE, ALABAMA Plus! Official Field Trip Guide for Educational Escapes included! Hello! TABLE OF CONTENTS 03 Space to Play The Huntsville/Madison County 26 Space to Perform Convention & Visitors Bureau is 28 Voluntourism SPACE your one-stop shop for planning group visits to North Alabama. 30 Additional Activities Services and materials provided Space to Rest to you upon request by the CVB 36 are free of charge: contact in- 39 Space At Our Table formation, motorcoach greeting, customized itineraries, familiar- 44 Step-On Guides & Motorcoaches ization tours, maps & brochures, 46 Hub & Spoke photos & videos, site inspections, TO and welcome bags. 48 Find Your Way WE ARE A PROUD MEMBER OF THE American Bus Association Alabama Motorcoach Association National Tour Association TOUR THEMES Southeast Tourism Society Explore Student & Youth Travel The Rocket City’s diverse landscape and unique blend of Association cultures creates endless possibilities for groups of all types. Trainees in Mission Control at U.S. Space Camp®. Travel South USA » African-American Heritage U.S. Travel Association » Flavors of the South & Craft Beer is a free, STUDENTS CAN EXPERIENCE » Arts & Shopping Educational Escapes FUN-FILLED, EDUCATIONAL curriculum-based service that promotes fun » Agricultural & Ecological ACTIVITIES THAT COMPLEMENT » Foundations of Faith and exciting educational opportunities in SIX FIELDS OF STUDY: » Performance unique environments outside the -

Rfhe Jfuntsvicce J-[Istorica[ (Rgview

rfhe JfuntsviCCe J-[istorica[ (Rgview Summer-Fall 2007 Volume 32 Number 2 C. S. S. Huntsville Sketch by Admiral David Glasgow Farragut (published (By ‘The J-Cuntsvitfe-'Madison County JiistoricaCSociety OFFICERS OF THE HUNTSVILLE-MADISON COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY PRESIDENT Bob Adams 1st Vice President (Programs).....................................Nancy Rohr 2nd Vice President (Membership)...................Linda Wright Riley Recording Secretary.................................................... Sharon Lang Corresponding Secretary............................... Dorothy Prince Luke Treasurer....................................................................... Wayne Smith BOARD OF DIRECTORS Jack Burwell Jim Lee* Sarah Huff Fisk* George A. Mahoney, Jr.* Rhonda Larkin David Milam* Dr. John Rison Jones* Jim Maples Joyce Smith* Virginia Kobler* Robin Brewer * Denotes Past Presidents Editor, The Huntsville Historical Review Jacquelyn Procter Reeves ‘The ‘MuntsvilTc ‘Historical ‘J{eviezv Summer - Fall 2007 Volume 32 Number 2 C.S.S. Huntsville Sketch by Admiral David Glasgow Farragut Published By The Huntsville-Madison County Historical Society © 2007 <27te !}{untsvitte HistoricaC%eviezv Volume 32 No. 2 Summer - Fall 2007 ‘TaBfe O f Contents President’s Page................................................................................................5 Editor’s Notes ................................................................................................7 Ships Named Huntsville..................................................................................9