A History and Analysis of Forest of Dean Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executive Summary

FOREST OF DEAN DISTRICT COUNCIL 2011 Air Quality Progress Report for Forest of Dean District 2011 In fulfillment of Part IV of the Environment Act 1995 Local Air Quality Management Chris J Ball Local Authority Officer Environmental Protection & Licensing Officer Department Environmental Protection & Licensing Forest of Dean District Council Address Council Offices High Street Coleford Gloucestershire GL16 8HG Telephone 01594 812429 E-mail [email protected] Report Reference number 2011AQPR Date May 2011 _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Forest of Dean District Council Air Quality Progress Report 2011 Executive Summary The 2011 Progress Report provides an update on the air quality issues affecting Forest of Dean district, including results of pollutant monitoring and information on new residential, industrial and transport developments that might affect air quality in the district. In 1995, the Environment Act provided for a National Air Quality Strategy requiring local authorities to carry out Reviews and Assessments of the air quality in their area for seven specific pollutants. These are; carbon monoxide (CO), benzene, 1, 3-butadiene, nitrogen dioxide (NO2), lead, sulphur dioxide (SO2) and PM10 (Particles under 10μm in diameter). This Air Quality Progress Report concluded the following: Five sites in the town of Lydney exceeded the nitrogen dioxide annual mean objective of 40μg/m3. These sites are within the Lydney Air Quality Management Area, which was declared in July 2010. No other pollutants exceeded their respective annual mean concentrations. There are no other road traffic sources of concern within Forest of Dean District Council‟s administrative area. There are no other transport sources of concern within Forest of Dean District Council‟s administrative area. -

Hereford to Ross-On-Wye & Gloucester Gloucester to Ross-On

Valid from 5 January 2020 Page 1 of 2 33 Gloucester to Ross-on-Wye & Hereford MONDAYS TO SATURDAYS except Bank Holiday Mondays MF MF Sat Sat MF Sat MF Sat MF 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 Gloucester Transport Hub [H] 0640 0740 0745 0850 0950 1050 1150 1250 1350 1450 1450 1550 1600 1650 1710 1750 Churcham Bulley Lane 0651 0752 0759 0904 1004 1104 1204 1304 1404 1504 1504 1604 1614 1704 1724 1804 Huntley Red Lion 0655 0756 0803 0908 1008 1108 1208 1308 1408 1508 1508 1608 1618 1708 1728 1808 Mitcheldean Lamb 0706 0808 0814 0919 1019 1119 1219 1319 1419 1519 1519 1619 1629 1719 1739 1819 Lea The Crown 0715 0817 0823 0928 1028 1128 1228 1328 1428 1528 1528 1628 1638 1728 1748 1828 Pontshill Postbox - 0822 - - - - - - - - - - - - - Weston-u-Penyard Penyard Gardens 0720 0826 0828 0933 1033 1133 1233 1333 1433 1533 1533 1633 1643 1733 1753 1833 John Kyrle High School - 0835 - - - - - - - - - - - - - Ross-on-Wye Cantilupe Road [1] arr. 0730 0840 0835 0940 1040 1140 1240 1340 1440 1540 1540 1640 1650 1740 1800 1840 q q q q q q q q q q q q q q Ross-on-Wye Cantilupe Road [1] dep. 0635 0735 0745 0845 0845 0845 0945 1045 1145 1245 1345 1445 1545 1545 1645 1655 1845 John Kyrle High School - - - - - - - - - - - - - 1550 - - - Peterstow Post Offi ce 0647 0747 0757 0857 0857 0857 0957 1057 1157 1257 1357 1457 1557 1602 1657 1707 1857 Kingsthorne Little Birch Turn 0702 0802 0812 0912 0912 0912 1012 1112 1212 1312 1412 1512 1612 1617 1712 1722 1912 Hereford Bridge Street 0717 0827 0827 0927 0927 0927 1027 1127 1227 1327 1427 1527 1627 1632 1727 1737 1927 Hereford Railway Station 0725 0835 0835 0935 0935 0935 1035 1135 1235 1335 1435 1535 1635 1640 1735 1745 1935 MF Only runs on Mondays to Fridays. -

The Maples, Deans Walk, Harrow Hill, Drybrook, Gloucestershire, GL17 9JU Price: £ 345,000

The Maples, Deans Walk, Harrow Hill, Drybrook, Gloucestershire, GL17 9JU Price: £ 345,000 www.bidmeadcook.co.uk 21 High Street, Cinderford, Gloucestershire, GL14 2SE Tel: 01594 826213 Email: [email protected] A smartly presented two double bedroom detached Tenure bungalow situated in a pleasant sought after location with We are advised FREEHOLD, to be verified by your attached garage, off road parking, level gardens and solicitor. elevated views over Drybrook village and Ruardean Hill. Directions The accommodation comprises of entrance hall with two From our Cinderford office proceed down the High Street built-in double cupboards, lounge with views to the front, passing through Steam Mills, at the junction for the conservatory with French doors to the garden, front aspect A4136 bear right, continue through the traffic lights and kitchen/dining room with a range of fitted units and take the turning on the left to Harrow Hill. Continue over including integral electric oven, two double bedrooms, wet the hill and take the third right hand turn into Deans room, covered rear porch leading to the attached garage Walk. Proceed along this road where the property will be and utility room. The property also has Calor gas central found on the right hand side. heating system and double glazing. Entrance Hall Lounge 16'6" x 13'1" (5.03m x 4m) Conservatory 14'6" x 11'5" (4.42m x 3.48m) Kitchen/Dining Room 20' x 10'2" (6.1m x 3.1m) Bedroom One 13'3" x 12'6" (4.04m x 3.8m) Bedroom Two 12'9" x 10' (3.89m x 3.05m) Wet Room Rear Porch Utility Room Outside Gated access to the front of the property leads to the driveway which in turn leads to the attached GARAGE with up and over door. -

Vebraalto.Com

Magpies High Street The Pludds, Ruardean GL17 9TU £280,000 CHARACTERFUL THREE DOUBLE BEDROOM DETACHED COTTAGE in need of some updating throughout, situated in a SOUGHT AFTER LOCATION benefiting from OIL FIRED CENTRAL HEATING, DOUBLE GLAZING, REAR GARDEN with OUTBUILDINGS, DETACHED GARAGE and all being offered with NO ONWARD CHAIN. Ruardean has a range of local amenities to include post office, general store, garage, hairdresser, doctors surgery, 2 public houses, church and a primary school. There is a bus service to Gloucester and surrounding areas where a more comprehensive range of amenities can be found. The accommodation comprises ENTRANCE PORCH, ENTRANCE LOBBY, LOUNGE, SITTING ROOM, DINING ROOM and KITCHEN. Whilst to the first floor THREE DOUBLE BEDROOMS and BATHROOM. The property is accessed via a upvc door into: BEDROOM 1 SERVICES ENTRANCE PORCH 11'01 x 11'00 (3.38m x 3.35m) Mains water, mains electric, septic tank, oil. ceiling light, quarry tiled flooring. Wooden door into: Ceiling light, power points, radiator, built in storage cupboard, double glazed upvc window to front elevation enjoying views towards forest and woodland. WATER RATES ENTRANCE LOBBY To be advised. BEDROOM 2 Parquet flooring, stairs lead to the first floor. Door into: LOCAL AUTHORITY 10'11 x 8'02 (3.33m x 2.49m) Council Tax Band: D LOUNGE Ceiling light, radiator, power points, double glazed upvc window to front Forest of Dean District Council, Council Offices, High Street, Coleford, Glos. 22'04 x 10'05 (6.81m x 3.18m) elevation enjoying views towards forest and woodland. GL16 8HG. Ceiling light, wall light points, two radiators, power points, TV point, exposed wooden beams, feature fireplace, under stairs storage cupboard, double glazed BEDROOM 3 TENURE bay fronted windows to front and rear elevations overlooking the gardens. -

'Gold Status' Lydney Town Council Achieves

branch line. branch country country typical a of pace relaxing the experience to can get off to explore the local area and get and area local the explore to off get can a chance chance a 5 stations so you you so stations 5 with Railway Heritage d an Steam ET 4 15 GL dney, y L Road, Forest tation, S chard or N days ected sel Open 845840 01594 and from railway building. railway from and later benefited from the growth of the ironworks into a tinplate factory factory tinplate a into ironworks the of growth the from benefited later trade of the Forest of Dean began to transform Lydney’s economy, which which economy, Lydney’s transform to began Dean of Forest the of trade 19th century the building of a tramroad and harbour to serve the coal coal the serve to harbour and tramroad a of building the century 19th Lydney’s harbour area was always strategically important and in the early early the in and important strategically always was area harbour Lydney’s of the 17th century and the reclamation of saltmarsh in the early 18th. early the in saltmarsh of reclamation the and century 17th the of establishment of ironworks at the start start the at ironworks of establishment Its owners also profited from the the from profited also owners Its deposits, and extensive woodland. woodland. extensive and deposits, resources, including fisheries, mineral mineral fisheries, including resources, free cafe, and local farm shop and deli. and shop farm local and cafe, free Picture framing and gift shop. -

Council Tax Spending Plans 2021 to 2022

FOREST OF DEAN DISTRICT COUNCIL SPENDING PLANS 2021-22 The level of council tax Council tax is the main source of locally-raised income for this authority and is used to meet the difference between the amount a local authority wishes to spend and the amount it receives from other sources such as business rates and government grants. In determining the level of council tax payable, the Cabinet has borne in mind the difficult economic and financial climate that many of our residents face, although our funding from Central Government has declined sharply during the period 2010 to 2021 (although there has been increased funding in 2020-2021 to help with the impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic), with uncertainty over future funding levels after March 2022. With this in mind, the Council has to consider what level of increase in council tax is sustainable, without creating an increased risk of service cuts and/or larger tax increases in the future. The average council tax you will pay for services provided by the District Council is £189.03 for a Band D taxpayer equating to £3.64 per week. This is an increase of £5.00 over last year, equating to less than 10 pence per week. Service delivery The Council aims to maintain the delivery and high standard of its services to residents, protecting front line services within the reduced funding available. The Council has no funding gap in 2021-22 although we have increased costs, the continued impact of low interest rates on investment income, impact of Covid-19 Pandemic as well as additional government support throughout the pandemic. -

Finham Sewage Treatment Works Thermal Hydrolysis Process Plant and Biogas Upgrade Plant Variation Applications

Finham Sewage Treatment Works Thermal Hydrolysis Process Plant and Biogas Upgrade Plant Variation Applications | 0.2 July 2020 Severn Trent Water EPR/YP3995CD/V006 Thermal Hy drolysis Process Pla nt a nd Biogas Up gra de Plan t Va ria tion Ap plica tions Sever n Tr ent Wa ter Thermal Hydrolysis Process Plant and Biogas Upgrade Plant Variation Applications Finham Sewage Treatment Works Project No: Project Number Document Title: Thermal Hydrolysis Process Plant and Biogas Upgrade Plant Variation Applications Document No.: Revision: 0.2 Document Status: <DocSuitability> Date: July 2020 Client Name: Severn Trent Water Client No: EPR/YP3995CD/V006 Project Manager: Mark McAree Author: James Killick File Name: Document2 Jacobs U.K. Limited Jacobs House Shrewsbury Business Park Shrewsbury Shropshire SY2 6LG United Kingdom T +44 (0)1743 284 800 F +44 (0)1743 245 558 www.jacobs.com © Copyright 2019 Jacobs U.K. Limited. The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of Jacobs. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of Jacobs constitutes an infringement of copyright. Limitation: This document has been prepared on behalf of, and for the exclusive use of Jacobs’ client, and is subject to, and issued in accordance with, the provisions of the contract between Jacobs and the client. Jacobs accepts no liability or responsibility whatsoever for, or in respect of, any use of, or reliance upon, this document by any third party. Document history and status Revision Date Description Author Checked Reviewed Approved i Thermal Hydrolysis Process Plant and Biogas Upgrade Plant Variation Applications Contents Non-Technical Summary.................................................................................................................................................. -

2019/20 Authorities Monitoring Report

2019/20 Authorities monitoring report Forest of Dean District Council This report provides an assessment on how the Forest of Dean district is travelling in relation to its planning policy framework, over the course of the period from 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020. 1 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................ 2 District demographic profile and trends ...................................................................... 3 Progress of the Local Plan ....................................................................................... 11 Core Strategy ........................................................................................................... 13 Strategic vision for the area .................................................................................. 14 Spatial strategy ..................................................................................................... 17 Policy CSP.1 Design and environmental protection .............................................. 20 Policy CSP.2 Climate change ............................................................................... 24 Policy CSP.3 Sustainable energy use within development proposals ................... 27 Policy CSP.5 Housing ........................................................................................... 34 Policy CSP.6 Sites for gypsies, travellers and travelling show people .................. 43 Policy CSP.7 Economy ........................................................................................ -

Newnhamvisitormap

to Reinhill at The Hyde Newnham on Severn LINE Old Station Yard Guide for Visitors For more information about Newnham visit RAILWAY Newnham Allotments Earlybirds www.newnhamonsevern.co.uk Recycling WEST Toddler Group bins VIEW LANE Newnham Cricket & EAST Ground St. Peter's , HYDE VIEW C.E. Primary School Dean Forest Severn Farm on Gloucester Playground to LANE A48 Westbury Skateboard Minsterworth BMX Tennis & Netball Fish Courts Hut UNLAWATER Playing Field HYDE ROAD BANK CLIFF HYDE WHETSTONES LANE THE The STATION Vicarage ACACIA TERRACE CLOSE Toilets OAK HIGHFIELD Unlawater STATION House VILLAS The ROAD FREE Old PUBLIC Masonic Hall House SHEEN'S Mythe Car Terrace Bus Park MEADOW Smithyman Court Stop MEAD The STREET ORCHARD STATION Club HIGH KINGS RISE Mornington BEECHES Formerly Terrace ROAD ROAD The The George Drill Café Hall Langdons Nursery Cottonwood Bailey's HARRISON Old Chapel Stores Old Doctors Surgery STREET) Fabrics Wharf CLOSE & Upholstery BACK CLOSE (formerly RISE ALLSOPP Chemist ROAD QUEEN'S PENBY ACRE Veterinary Practice Rope ORCHARD CHURCH LAWN Walk STREET to Littledean The Black HIGH Hairdresser Clay Hill Potters, Pig The Grange Newnham Camphill Village Trust Armoury House Village Hall DEAN & Newnham Nab Hayden ROAD Community Cottages Lea Library Village Animal Pound SEVERN STREET SEVERN TERRACE Butcher Post Office Passage Beauty Salon House Newnham Wardrobe Joynes Meadow THE MERTONS Brightlands Apple Orchard St.Peters House Close The FerryFerry Riverdale (Ancient crossing) THE Apartments Casa Interiors (formerly GREEN Brightlands D School) A O R former H RC Victoria Hotel CHU The Nab Bus Post box Victoria Stop Garage Bus Peace Bus Stop Garden Stop Bus stop Churchyard Defibrillator Former castle ringwork nationally Viewing point important SevernSevern archaeological site Public seating StSt Peter's. -

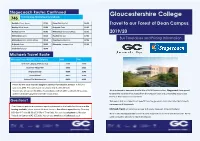

Forest-Of-Campus-Bus-Travel-1920.Pdf

Stagecoach Routes Continued Gloucestershire College 746 From Huntley, Mitcheldean & Drybrook Boxbush Manor House 07:51 Cinderford GlosCol 16:35 Travel to our Forest of Dean Campus Huntley White Horse 08:00 Drybrook Cross 16:43 Huntley Sawmill 08:02 Mitcheldean Dunstone Place 16:51 2019/20 Mitcheldean Lamb 08:12 Huntley Red Lion 17:02 Bus Timetables and Pricing Information Mitcheldean Dean Magna School 08:15 Churcham Bulley Lane 17:06 Drybrook Cross 08:25 Gloucester Transport Hub 17:20 Cinderford GlosCol 08:40 Michaels Travel Route Michaels Travel ROUTE 1—St Briavels AM PM St Briavels, playing fields bus stop 07:55 17:00 Clearwell, Village Hall 08:02 16:53 Sling Crossroads 08:07 16:48 Bream School 08:15 16:40 Parkend, The Woodman Inn 08:20 16:35 Cinderford Campus, Gloscol 08:35 16:20 Passes for this route must be bought in advance from Student Services. A full year pass costs £500. This can be paid via cash/card in Student Services. You can also set up a Direct Debit. A £100 deposit will be taken to secure the bus pass, We are pleased to announce that for the 2019/20 Academic Year, Stagecoach have agreed and then 8 monthly payments (October-May) of £50. to cover the majority of the routes from the Forest Of Dean and surrounding areas to our Forest of Dean Campus in Cinderford. Questions? This means that our students will benefit from the generous discounted rates that students can access with Stagecoach. If you have any queries or questions regarding transport to the Cinderford Campus or the funding available, please contact Student Services. -

The Residential Handbook Volunteer Info-Pack

The Residential Handbook Volunteer Info-Pack ASHA Centre, Gunn Mill House, Lower Spout Lane, Nr. Flaxley, Gloucestershire GL17 0EA, United Kingdom Tel. +44(0)1594 822330; e-mail: [email protected], website: www.ashacentre.org European Voluntary Service “Volunteer for Change” 11th edition THE ASHA CENTRE LONG-TERM EVS Project – 10 months Volunteers: 8 (1German, 1Slovenian, 1Romanian, 1Estonia, 1France, 1Greek, 1Spain, 1Czech,) 9TH OCTOBER 2018 – 10TH AUGUST 2019 FOREST OF DEAN - UK CONTENTS 1. ABOUT THE ASHA CENTRE (VISION, VALUES AND VENUE) 2. THE CORE TEAM – WHO IS WHO 3. VOLUNTEER PROFILE AND CODE OF CONDUCT 4. VOLUNTEER ACTIVITIES AND PROGRAMME 5. ACCOMODATION AGREEMENT (LIVING AT HILL HOUSE) 6. USEFUL INFORMATION AND PRACTICALITIES 7. WHAT YOU NEED TO DO NOW 8. TRAVELLING TO THE UK, GLOUCESTER AND ASHA CENTRE 9. REIMBURSEMENT OF TRAVEL COSTS 10. FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS 11. LINK TO PAST VOLUNTEERS TESTIMONALS 12. CONTACT US / PARTNERS ABOUT THE ASHA CENTRE (VISION, VALUES AND VENUE) The ASHA Centre is a UK charity working for the empowerment of young people, sustainable development and peace & reconciliation worldwide. The Centre is a hub of intercultural activities, hosting a range of educational, performing arts and environment-based programmes throughout the year. The ASHA Centre is a unique venue. It is located within the magnificent scenery of the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire, UK and has a 4-acre biodynamic/organic fruit, vegetable garden, herb and rose garden, as well as a secret garden and Hobbiton play area. The Centre is a renowned venue for youth empowerment and leadership and is one of the foremost organisations in the UK that works within the Erasmus+ programme, which is administered and supported the by the British Council and Ecorys UK - National Agency. -

CENTRE for ARCHAEOLOGY Centre for Archaeology Report 25/2001

S ("-1 1<. 6?r1 36325 a ~I~ 6503 ENGLISH HERITAGE Report 25/200 I Tree-Ring Analysis of Timbers from Gunns Mills, Spout Lane, Abenhall, Near Mitcheldean, Gloucestershire RE Howard, R R Laxton and C D litton CENTRE FOR ARCHAEOLOGY Centre for Archaeology Report 25/2001 Tree-Ring Analysis of Timbers from Gunns Mills, Spout Lane, Abenhall, Near Mitcheldean, Gloucestershire R E Howard, R R Laxton & C D Litton © English Heritage 2001 ISSN 1473-9224 The Centre for Archaeology Reports Series incorporates the former Ancient Monuments LaboratOlY Report Series. Copies of Ancient Monuments LaboratolY Reports will continue to be available from the Centrefor Archaeology (see back ofcover for details). Centre for Archaeology Report 25/2001 Tree-Ring Analysis of Timbers from Gunns Mills, Spout Lane, Abenhall, Near Mitcheldean, Gloucestershire RE Howard, R R Laxton & C D Litton Summary Fifteen samples from the timber portion of this blast furnace were analysed by tree-ring dating. This analysis produced a single site chronology of nine samples, the 244 rings it contains spanning the period AD 1438 - AD 1681. Interpretation of the sapwood, and the relative positions of the heartwoodlsapwood boundaries on the dated samples, suggests that the timbers represented, all from the northern half of the timber building, were felled in late AD 1681 or early AD 1682. This felling took place as part of a reconstruction programme, known to have taken place in AD 1682 3 and does not date to the cAD 1740 conversion of the building to a paper milL Keywords Dendrochronology Standing Building Authors' address University of Nottingham, University Park, Nottingham, NG7 2RD.