Leon Trotsky's Adventure in American Radical Politics. 1935–1937

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reichman on Linden, 'Western Marxism and the Soviet Union: a Survey of Critial Theories and Debates Since 1917'

H-Russia Reichman on Linden, 'Western Marxism and the Soviet Union: A Survey of Critial Theories and Debates since 1917' Review published on Monday, November 10, 2008 Marcel van der Linden. Western Marxism and the Soviet Union: A Survey of Critial Theories and Debates since 1917. Leiden: Brill, 2007. ix + 380 pp. $139.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-90-04-15875-7. Reviewed by Henry Reichman Published on H-Russia (November, 2008) Commissioned by Nellie H. Ohr A Fading Tradition This is a revised, corrected, updated, and expanded version of a work that began as a PhD dissertation and was originally published in Dutch in 1989 and again in German in 1992. Marcel van der Linden, a labor historian at Amsterdam University and executive editor of theInternational Review of Social History, summarizes an extraordinarily broad range of Western Marxist thinkers in an effort to understand how Marxists who were politically independent of the Soviet Union "theoretically interpreted developments in the Soviet Union" (p. 4). Noting that "in the history of ideas Marxist theories have not received the attention they deserve" (p. 2) and that "the 'Russian Question' was an absolutely central problem for Marxism in the twentieth century" (p. 1), van der Linden seeks simultaneously to shed light on both the Soviet experience and "the historical development of Marxist thought" (p. 1), succeeding perhaps more in the latter goal than the former. The book opens with a brief introduction, which postulates that the development of Western Marxist thinking about the Soviet Union was shaped by three "contextual clusters:" 1) "The general theory of the forms of society (modes of production) and their succession" adopted by differing Marxist thinkers; 2) the changing "perception of stability and dynamism of Western capitalism"; and 3) the various ways "in which the stability and dynamism of Soviet society was perceived" (pp. -

Raya Dunayevskaya Papers

THE RAYA DUNAYEVSKAYA COLLECTION Marxist-Humanism: Its Origins and Development in America 1941 - 1969 2 1/2 linear feet Accession Number 363 L.C. Number ________ The papers of Raya Dunayevskaya were placed in the Archives of Labor History and Urban Affairs in J u l y of 1969 by Raya Dunayevskaya and were opened for research in May 1970. Raya Dunayevskaya has devoted her l i f e to the Marxist movement, and has devel- oped a revolutionary body of ideas: the theory of state-capitalism; and the continuity and dis-continuity of the Hegelian dialectic in Marx's global con- cept of philosophy and revolution. Born in Russia, she was Secretary to Leon Trotsky in exile in Mexico in 1937- 38, during the period of the Moscow Trials and the Dewey Commission of Inquiry into the charges made against Trotsky in those Trials. She broke politically with Trotsky in 1939, at the outset of World War II, in opposition to his defense of the Russian state, and began a comprehensive study of the i n i t i a l three Five-Year Plans, which led to her analysis that Russia is a state-capitalist society. She was co-founder of the political "State-Capitalist" Tendency within the Trotskyist movement in the 1940's, which was known as Johnson-Forest. Her translation into English of "Teaching of Economics in the Soviet Union" from Pod Znamenem Marxizma, together with her commentary, "A New Revision of Marxian Economics", appeared in the American Economic Review in 1944, and touched off an international debate among theoreticians. -

Albert Glotzer Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1t1n989d No online items Register of the Albert Glotzer papers Processed by Dale Reed. Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 2010 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Register of the Albert Glotzer 91006 1 papers Register of the Albert Glotzer papers Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Processed by: Dale Reed Date Completed: 2010 Encoded by: Machine-readable finding aid derived from Microsoft Word and MARC record by Supriya Wronkiewicz. © 2010 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Title: Albert Glotzer papers Dates: 1919-1994 Collection Number: 91006 Creator: Glotzer, Albert, 1908-1999 Collection Size: 67 manuscript boxes, 6 envelopes (27.7 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: Correspondence, writings, minutes, internal bulletins and other internal party documents, legal documents, and printed matter, relating to Leon Trotsky, the development of American Trotskyism from 1928 until the split in the Socialist Workers Party in 1940, the development of the Workers Party and its successor, the Independent Socialist League, from that time until its merger with the Socialist Party in 1958, Trotskyism abroad, the Dewey Commission hearings of 1937, legal efforts of the Independent Socialist League to secure its removal from the Attorney General's list of subversive organizations, and the political development of the Socialist Party and its successor, Social Democrats, U.S.A., after 1958. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Languages: English Access Collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items. -

By Philip Roth

The Best of the 60s Articles March 1961 Writing American Fiction Philip Roth December 1961 Eichmann’s Victims and the Unheard Testimony Elie Weisel September 1961 Is New York City Ungovernable? Nathan Glazer May 1962 Yiddish: Past, Present, and Perfect By Lucy S. Dawidowicz August 1962 Edmund Wilson’s Civil War By Robert Penn Warren January 1963 Jewish & Other Nationalisms By H.R. Trevor-Roper February 1963 My Negro Problem—and Ours By Norman Podhoretz August 1964 The Civil Rights Act of 1964 By Alexander M. Bickel October 1964 On Becoming a Writer By Ralph Ellison November 1964 ‘I’m Sorry, Dear’ By Leslie H. Farber August 1965 American Catholicism after the Council By Michael Novak March 1966 Modes and Mutations: Quick Comments on the Modern American Novel By Norman Mailer May 1966 Young in the Thirties By Lionel Trilling November 1966 Koufax the Incomparable By Mordecai Richler June 1967 Jerusalem and Athens: Some Introductory Reflections By Leo Strauss November 1967 The American Left & Israel By Martin Peretz August 1968 Jewish Faith and the Holocaust: A Fragment By Emil L. Fackenheim October 1968 The New York Intellectuals: A Chronicle & a Critique By Irving Howe March 1961 Writing American Fiction By Philip Roth EVERAL winters back, while I was living in Chicago, the city was shocked and mystified by the death of two teenage girls. So far as I know the popu- lace is mystified still; as for the shock, Chicago is Chicago, and one week’s dismemberment fades into the next’s. The victims this particular year were sisters. They went off one December night to see an Elvis Presley movie, for the sixth or seventh time we are told, and never came home. -

Andre Malraux's Devotion to Caesarism Erik Meddles Regis University

Regis University ePublications at Regis University All Regis University Theses Spring 2010 Partisan of Greatness: Andre Malraux's Devotion to Caesarism Erik Meddles Regis University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Meddles, Erik, "Partisan of Greatness: Andre Malraux's Devotion to Caesarism" (2010). All Regis University Theses. 544. https://epublications.regis.edu/theses/544 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Regis University Theses by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Regis University Regis College Honors Theses Disclaimer Use of the materials available in the Regis University Thesis Collection (“Collection”) is limited and restricted to those users who agree to comply with the following terms of use. Regis University reserves the right to deny access to the Collection to any person who violates these terms of use or who seeks to or does alter, avoid or supersede the functional conditions, restrictions and limitations of the Collection. The site may be used only for lawful purposes. The user is solely responsible for knowing and adhering to any and all applicable laws, rules, and regulations relating or pertaining to use of the Collection. All content in this Collection is owned by and subject to the exclusive control of Regis University and the authors of the materials. It is available only for research purposes and may not be used in violation of copyright laws or for unlawful purposes. -

Internationalist 29

Summer 2009 No. 29 The $2 2 Internationalist For Workers Revolution Against the Dictatorship! Upheaval in Iran Getty Images ppp. 10-29 No to All Wings of the Mullah Regime! U.S. Imperialism Hands Off! Dossier: Workers’ Struggles in Mexico . 46-67 Honduras: Obama Administration’s First Coup. 80, 40 Australia $2, Brazil R$3, Britain £1.50, Britain: Labourites and the Police. 30 Canada $2, Europe 2, India Rs. 50, Japan ¥200, Mexico $10, Philippines 50 p, War On Abortion Rights Escalates. 7 S. Africa R10, S. Korea 2,000 won 2 The Internationalist Summer 2009 In this issue... How the “Anti-War” Movement Paved Order Now! the Way for Obama's War .................. 4 Assassination of Courageous Doctor This 56-page bulletin documents the fight of the in Wichita: War on Abortion Rights Internationalist Group to Escalates............................................. 7 defeat the imperialist war Mass Protests Rock Iran: No to All with working-class Wings of the Mullah Regime!.......... 10 action, and the struggle of the West Coast Election Fraud? Undoubtedly, longshore union against But Media Ignored Ahmadinejad government strike- Support ............................................. 15 breaking and racist attacks. Iran’s Islamic Republic in Turmoil – What Program for Struggle? ........... 20 US$2 Her Majesty’s Social Democrats in Bed with the Police ..................... 30 Order from/make checks payable to: Mundial Publications, Box 3321, Brazilian Trotskyists Fought to Church Street Station, New York, New York 10008, U.S.A. Drive Police Out of the Unions ....... 38 Honduras: Coup d’État in the Maquiladora Republic ..................... 40 Visit the League for the Fourth International/ Two Years of the Cananea Strike: Internationalist Group on the Internet Mobilize to Defend Striking http://www.internationalist.org Mexican Mine Workers! .................. -

Sam Gordon Bio-Bibliographical Sketch

Lubitz' TrotskyanaNet Sam Gordon Bio-Bibliographical Sketch Contents: • Basic biographical data • Biographical sketch • Selective bibliography • Notes on archives Basic biographical data Name: Sam Gordon Other names (by-names, pseud., etc.): Burton ; Drake ; Harry ; Joe ; Joad ; J.S. ; Paul G. Stevens ; J. Stuart ; J.B. Stuart ; J.E.B. Stuart ; Ted ; Tom Date and place of birth: May 5, 1910, ??? (Austria-Hungary) Date and place of death: March 12, 1982, London (Britain) Nationality: USA Occupations, careers, etc.: Printer, journalist, translator, seaman, organizer Time of activity in Trotskyist movement: 1929 - 1982 (lifelong Trotskyist) Biographical sketch Sam Gordon was an outstanding Trotskyist who during the 1940s played an eminent rôle as a liaison man between the American SWP and the European Trotskyists as well as within the leading bodies of the Fourth In ternational. The following biographical sketch is chiefly based on the material listed in the last paragraph of the Selective bibliography section below. Sam Gordon1 was born on May 5, 1910 as a son of Yiddish speaking Jewish parents living in that part of Poland which then belonged to the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. However, when Sam was still a baby, the family moved to Vienna, the Austrian capital, thus the boy grew up in a German speaking en vironment. In 1920, the family went to New York (USA) where Sam Gordon rapidly learnt English and got naturalized under the Americanized name of Gordon; as an adolescent he was fluent in three languages. In the early 1940s, Gordon got acquainted with Mildred Fellerman (b. 1923), a British teacher and Labour Party activist; when the two met again in Paris in 1947, they fell in love, and in 1948 they got married in the United States; in the 1950s they got a son. -

Oral History Transcript T-0217, Interview with David Burbank

ORAL HISTORY T-0217 INTERVIEW WITH DAVID BURBANK INTERVIEWED BY NOEL DARK SOCIALIST PARTY PROJECT NOVEMBER 29, 1972 This transcript is a part of the Oral History Collection (S0829), available at The State Historical Society of Missouri. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. My name is Noel Clark. I am a graduate student at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. The date is November 29, 1972. I am going to talk this evening to Mr. David Burbank about the Socialist Party in the State of Missouri. CLARK: Mr. Burbank, would you mind, first of all, saying your name? BURBANK: Yes, I am David Burbank. CLARK: ...and your address. BURBANK: My address is 300 Mansion Center, St. Louis. CLARK: Okay. Mr. Burbank, would you mind giving us a short history on the Socialist Party as you first became acquainted with it? BURBANK: Well, I think I might start out by giving a little bit of background. As you probably know, the Socialist Party was greatly reduced after World War I. The Red scares and the Communist split reduced it nationally to very little. There were several cities where they had originally been very strong before World War I and even during World War I. St. Louis was one of them. There was a very large German population and this party here was, to a very large extent, a German organization. It had been so for a long time. The German Socialists were active in various German Unions, like the brewery works, the carpenters, machinists and so on, and exercised considerable influence in these unions. -

Socialism in One Country” Promoting National Identity Based on Class Identification

“Socialism in One Country” Promoting National Identity Based on Class Identification IVAN SZPAKOWSKI The Russian Empire of the Romanovs spanned thousands of miles from the Baltic to the Pacific, with a population of millions drawn from dozens of ethnic groups. Following the Russian Civil War, the Bolsheviks inherited the problem of holding together such a heterogeneous body. At the same time, they were forced to uphold Marxist ideology demanding worldwide revolution of the proletariat while facing the reality that despite the turmoil following the First World War no such revolution was forthcoming. In 1924 the rising Joseph Stalin, along with Nikolai Bukharin, devised the theory of “Socialism in One Country” which would become the solution to many of these problems facing the Bolsheviks. First of all, it proclaimed the ability of socialism to succeed in the Soviet Union alone, without foreign aid. Additionally, it marked a change from Lenin’s policy of self-determination for the Soviet Union’s constituent nations to Stalin’s policy of a compulsory unitary state. These non-Russian ethnics were systematically and firmly incorporated into the Soviet Union by the promotion of a proletariat class mentality. The development of the theory and policy of “Socialism in One Country” thus served to forge the unitary national identity of the Soviet Union around the concept of common Soviet class identity. The examination of this policy’s role in building a new form of national identity is dependant on a variety of sources, grouped into several subject areas. First, the origin of the term “Socialism in One Country,” its original meaning and its interpretation can be found in the speeches and writings of prominent contemporary communist leaders, chief among them: Stalin and Trotsky. -

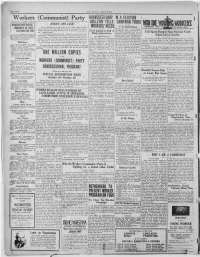

One Million Copies

Page Four ’HE DAILY WORKER Workers (Communist) Party HARVESTER SHOP W. f>. ELECTION ‘ BULLETIN TELLS CAMPAIGN TOURS WORKERS PARTY ENTERS HERE’S ONE CASE! VATU IKE- UmS CONDUCTED "One fellow-worker In my shop said to me: "Well, maybe you guys WORKERS' NEEDS C. E. Ruthenberg i YO&C WORKEQS LEA6UE CANDIDATES IN STATE are all right for the time when there’ll be a revolution here like in General Secretary of the Workers (Communist) Russia. But there ain’t any revolution now—so what have you got to Third Edition Is Full of Party, is starting off his ELECTIONS THIS YEAR say. I guess nothing.’’ big election campaign tour with a Full Speed Ahead to Open National Youth "I showed him I gave Meaty Information meeting at Buffalo on October 14. The soon he was wrong. him a copy of the CON- * s'" In a number of states nominations have meeting will be held been filed by petition while In othere the GRESSIONAL PROGRAM OF THE PARTY proved to that at Workers' Hall, School End of October petition and him we campaion ia still in progress to By MARTIN ABERN. 36 AVest Huron street. Comrade Ruth- • ! place have something to say about every question that la of Interest to Workers (Communist) Party can- the enberg will speak Work- didates officially on ballots. The third issue of the Harvester on: “What a last day of October see the long-awaited opening of the workers. He read It and then the next day he said that he for The will the NA- Nominations officially filed: was us Bulletin, Issued by McCormick ers’ and Farmers’ Government Will and was going to vote us and try get the TIONAL TRAINING SCHOOL of the YOUNG WORKERS COMMUNIST for to others to vote for us. -

Library of Social History Collection, Date (Inclusive): 1894-2000 Collection Number: 91004 Creator: Library of Social History (New York, N

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt900021c7 No online items Register of the Library of Social History Collection Prepared by Dale Reed Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 2003 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Register of the Library of Social History 91004 1 Collection Register of the Library of Social History Collection Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Contact Information Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] Prepared by: Dale Reed Date Completed: 2000 Encoded by: ByteManagers using OAC finding aid conversion service specifications © 2003 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Library of Social History collection, Date (inclusive): 1894-2000 Collection number: 91004 Creator: Library of Social History (New York, N. Y.) Extent: 299 manuscript boxes, 2 card file boxes, 2 oversize boxes157 linear feet Repository: Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: Serial issues, pamphlets, leaflets, internal bulletins, other internal documents, and electoral and convention material, issued by Trotskyist groups throughout the world, and especially in the United States, Latin America and Western Europe, and including some materials issued by non-Trotskyist left-wing groups; speeches and writings by Fidel Castro and other Cuban leaders, and printed matter relating to Cuba, with indexes thereto; speeches and writings by Nicaraguan Sandinista leaders; and public and internal issuances of the New Jewel Movement of Grenada and its leaders, and printed and other material relating to the movement and its overthrow. -

Capitalism Unchallenged : a Sketch of Canadian Communism, 1939 - 1949

CAPITALISM UNCHALLENGED : A SKETCH OF CANADIAN COMMUNISM, 1939 - 1949 Donald William Muldoon B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1974 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History @ DONALD WILLIAM MULDOON 1977 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY February 1977 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Donald William Muldoon Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: Capitalism Unchallenged : A Sketch of Canadian Communism, 1939 - 1949. Examining Committee8 ., Chair~ergan: .. * ,,. Mike Fellman I Dr. J. Martin Kitchen senid; Supervisor . - Dr.- --in Fisher - &r. Ivan Avakumovic Professor of History University of British Columbia PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis or dissertation (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for mu1 tiple copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesi s/Di ssertation : Author : (signature) (name) (date) ABSTRACT The decade following the outbreak of war in September 1939 was a remarkable one for the Communist Party of Canada and its successor the Labor Progressive Party.