PROGRAM NOTES Silvestre Revueltas Suite from Redes (Nets)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Activity Sheet

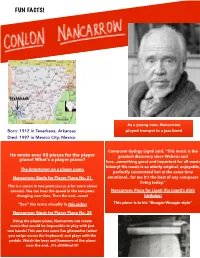

FUN FACTS! As a young man, Nancarrow Born: 1912 in Texarkana, Arkansas played trumpet in a jazz band Died: 1997 in Mexico City, Mexico Composer György Ligeti said, “This music is the He wrote over 50 pieces for the player greatest discovery since Webern and piano! What’s a player piano? Ives...something great and important for all music history! His music is so utterly original, enjoyable, The Entertainer on a player piano perfectly constructed but at the same time Nancarrow: Study for Player Piano No. 21 emotional...for me it’s the best of any composer living today.” This is a canon in two parts (see p. 6 for more about canons). You can hear the speed in the two parts Nancarrow: Piece for Ligeti (for Ligeti’s 65th changing over time. Then the end...wow! birthday) “See” the score visually in this video This piece is in his “Boogie-Woogie style” Nancarrow: Study for Player Piano No. 25 Using the player piano, Nancarrow can create music that would be impossible to play with just two hands! This one has some fun glissandos (when you swipe across the keyboard) and plays with the pedals. Watch the keys and hammers of the piano near the end...it’s aliiiiiiive!!!!! 1 FUN FACTS! Population: 130 million Capital: Mexico City (Pop: 9 million) Languages: Spanish and over 60 indigenous languages Currency: Peso Highest Peak: Pico de Orizaba volcano, 18,491 ft Flag: Legend says that the Aztecs settled and built their capital city (Tenochtitlan, Mexico City today) on the spot where they saw an eagle perched on a cactus, eating a snake. -

COPLAND, CHÁVEZ, and PAN-AMERICANISM by Candice

Blurring the Border: Copland, Chávez, and Pan-Americanism Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Sierra, Candice Priscilla Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 23:10:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/634377 BLURRING THE BORDER: COPLAND, CHÁVEZ, AND PAN-AMERICANISM by Candice Priscilla Sierra ________________________________ Copyright © Candice Priscilla Sierra 2019 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2019 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Musical Examples ……...……………………………………………………………… 4 Abstract………………...……………………………………………………………….……... 5 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………. 6 Chapter 1: Setting the Stage: Similarities in Upbringing and Early Education……………… 11 Chapter 2: Pan-American Identity and the Departure From European Traditions…………... 22 Chapter 3: A Populist Approach to Politics, Music, and the Working Class……………....… 39 Chapter 4: Latin American Impressions: Folk Song, Mexicanidad, and Copland’s New Career Paths………………………………………………………….…. 53 Chapter 5: Musical Aesthetics and Comparisons…………………………………………...... 64 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………. 82 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………….. 85 4 LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES Example 1. Chávez, Sinfonía India (1935–1936), r17-1 to r18+3……………………………... 69 Example 2. Copland, Three Latin American Sketches: No. 3, Danza de Jalisco (1959–1972), r180+4 to r180+8……………………………………………………………………...... 70 Example 3. Chávez, Sinfonía India (1935–1936), r79-2 to r80+1…………………………….. -

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Phyllis Curtin - Box 1 Folder# Title: Photographs Folder# F3 Clothes by Worth of Paris (1900) Brooklyn Academy F3 F4 P.C. recording F4 F7 P. C. concert version Rosenkavalier Philadelphia F7 FS P.C. with Russell Stanger· FS F9 P.C. with Robert Shaw F9 FIO P.C. with Ned Rorem Fl0 F11 P.C. with Gerald Moore Fl I F12 P.C. with Andre Kostelanetz (Promenade Concerts) F12 F13 P.C. with Carlylse Floyd F13 F14 P.C. with Family (photo of Cooke photographing Phyllis) FI4 FIS P.C. with Ryan Edwards (Pianist) FIS F16 P.C. with Aaron Copland (televised from P.C. 's home - Dickinson Songs) F16 F17 P.C. with Leonard Bernstein Fl 7 F18 Concert rehearsals Fl8 FIS - Gunther Schuller Fl 8 FIS -Leontyne Price in Vienna FIS F18 -others F18 F19 P.C. with hairdresser Nina Lawson (good backstage photo) FI9 F20 P.C. with Darius Milhaud F20 F21 P.C. with Composers & Conductors F21 F21 -Eugene Ormandy F21 F21 -Benjamin Britten - Premiere War Requiem F2I F22 P.C. at White House (Fords) F22 F23 P.C. teaching (Yale) F23 F25 P.C. in Tel Aviv and U.N. F25 F26 P. C. teaching (Tanglewood) F26 F27 P. C. in Sydney, Australia - Construction of Opera House F27 F2S P.C. in Ipswich in Rehearsal (Castle Hill?) F2S F28 -P.C. in Hamburg (large photo) F2S F30 P.C. in Hamburg (Strauss I00th anniversary) F30 F31 P. C. in Munich - German TV F31 F32 P.C. -

The Function of Music in Sound Film

THE FUNCTION OF MUSIC IN SOUND FILM By MARIAN HANNAH WINTER o MANY the most interesting domain of functional music is the sound film, yet the literature on it includes only one major work—Kurt London's "Film Music" (1936), a general history that contains much useful information, but unfortunately omits vital material on French and German avant-garde film music as well as on film music of the Russians and Americans. Carlos Chavez provides a stimulating forecast of sound-film possibilities in "Toward a New Music" (1937). Two short chapters by V. I. Pudovkin in his "Film Technique" (1933) are brilliant theoretical treatises by one of the foremost figures in cinema. There is an ex- tensive periodical literature, ranging from considered expositions of the composer's function in film production to brief cultist mani- festos. Early movies were essentially action in a simplified, super- heroic style. For these films an emotional index of familiar music was compiled by the lone pianist who was musical director and performer. As motion-picture output expanded, demands on the pianist became more complex; a logical development was the com- pilation of musical themes for love, grief, hate, pursuit, and other cinematic fundamentals, in a volume from which the pianist might assemble any accompaniment, supplying a few modulations for transition from one theme to another. Most notable of the collec- tions was the Kinotek of Giuseppe Becce: A standard work of the kind in the United States was Erno Rapee's "Motion Picture Moods". During the early years of motion pictures in America few original film scores were composed: D. -

Collective Difference: the Pan-American Association of Composers and Pan- American Ideology in Music, 1925-1945 Stephanie N

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Collective Difference: The Pan-American Association of Composers and Pan- American Ideology in Music, 1925-1945 Stephanie N. Stallings Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC COLLECTIVE DIFFERENCE: THE PAN-AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF COMPOSERS AND PAN-AMERICAN IDEOLOGY IN MUSIC, 1925-1945 By STEPHANIE N. STALLINGS A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2009 Copyright © 2009 Stephanie N. Stallings All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephanie N. Stallings defended on April 20, 2009. ______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee Member ______________________________ Charles Brewer Committee Member ______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my warmest thanks to my dissertation advisor, Denise Von Glahn. Without her excellent guidance, steadfast moral support, thoughtfulness, and creativity, this dissertation never would have come to fruition. I am also grateful to the rest of my dissertation committee, Charles Brewer, Evan Jones, and Douglass Seaton, for their wisdom. Similarly, each member of the Musicology faculty at Florida State University has provided me with a different model for scholarly excellence in “capital M Musicology.” The FSU Society for Musicology has been a wonderful support system throughout my tenure at Florida State. -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

Gershwin, Copland, Lecuoña, Chávez, and Revueltas

Latin Dance-Rhythm Influences in Early Twentieth Century American Music: Gershwin, Copland, Lecuoña, Chávez, and Revueltas Mariesse Oualline Samuels Herrera Elementary School INTRODUCTION In June 2003, the U. S. Census Bureau released new statistics. The Latino group in the United States had grown officially to be the country’s largest minority at 38.8 million, exceeding African Americans by approximately 2.2 million. The student profile of the school where I teach (Herrera Elementary, Houston Independent School District) is 96% Hispanic, 3% Anglo, and 1% African-American. Since many of the Hispanic students are often immigrants from Mexico or Central America, or children of immigrants, finding the common ground between American music and the music of their indigenous countries is often a first step towards establishing a positive learning relationship. With this unit, I aim to introduce students to a few works by Gershwin and Copland that establish connections with Latin American music and to compare these to the works of Latin American composers. All of them have blended the European symphonic styles with indigenous folk music, creating a new strand of world music. The topic of Latin dance influences at first brought to mind Mexico and mariachi ensembles, probably because in South Texas, we hear Mexican folk music in neighborhood restaurants, at weddings and birthday parties, at political events, and even at the airports. Whether it is a trio of guitars, a group of folkloric dancers, or a full mariachi band, the Mexican folk music tradition is part of the Tex-Mex cultural blend. The same holds true in New Mexico, Arizona, and California. -

The Society for American Music

The Society for American Music Thirty-Fourth Annual Conference 1 RIDERS IN THE SKY 2008 Honorary Members Riders In The Sky are truly exceptional. By definition, empirical data, and critical acclaim, they stand “hats & shoulders” above the rest of the purveyors of C & W – “Comedy & Western!” For thirty years Riders In The Sky have been keepers of the flame passed on by the Sons of the Pioneers, Gene Autry and Roy Rogers, reviving and revitalizing the genre. And while remaining true to the integrity of Western music, they have themselves become modern-day icons by branding the genre with their own legendary wacky humor and way-out Western wit, and all along encouraging buckaroos and buckarettes to live life “The Cowboy Way!” 2 Society for American Music Thirty-Fourth Annual Conference 3 Society for American Music Thirty-Fourth Annual Conference Hosted by Trinity University 27 February - 2 March 2008 San Antonio, Texas 2 Society for American Music Thirty-Fourth Annual Conference 3 4 Society for American Music Thirty-Fourth Annual Conference 5 Welcome to the 34th annual conference of the Society for American Music! This wonderful meeting is a historic watershed for our Society as we explore the musics of our neighbors to the South. Our honorary member this year is the award-winning group, Riders In The Sky, who will join the San Antonio Symphony for an unusual concert of American music (and comedy). We will undoubtedly have many new members attending this conference. I hope you will welcome them and make them feel “at home.” That’s what SAM is about! Many thanks to Kay Norton and her committee for their exceptional program and to Carl Leafstedt and his committee for their meticulous attention to the many challenges of local arrangements. -

Class Guide Summer 2021 Music of Our Time

Class Guide Summer 2021 Class 5: July 29, 2021 Music of Our Time Repertoire Click on the links to enjoy A Kaleidoscope Donato’s favorite YouTube recordings. Description If you find a broken link, please just Google the Beginning in the early 20th century and continuing piece instead. to the present day, the music of the modern world Claude Debussy: Nuages ofers a rich and multi-varied array of styles. We’ll George Gershwin: Swanee and dig into this kaleidoscopic banquet, beginning with Prelude No. 1 Claude Debussy and moving through jazz-inspired Steve Reich: Music for 18 composers such as George Gershwin, reaching the Musicians (excerpt) 21st century with works written within the past few Jessie Montgomery: Banner years. Professor Scott Foglesong and California Symphony Music Director Donato Cabrera will close Latinx Composers (all out A Fresh Look with a discussion about the past, excerpts) present, and future of orchestral music. Heitor Villa-Lobos: Symphony No. 9, II Outline Mozart Comargo Guarnieri: • The First True Modernist Abertura Concertante Gabriela Ortiz: Denibée » Debussy Roberto Sierra: Sinfonia No. 3 La • • Broadway & Jazz in the Concert Hall Salsa, IV » Gershwin Alberto Ginastera: Popul Vuh, El • Fusion Influence Cerebralism, Atonality Amanecer de la Humanidad Gabriela Lena Frank: Hilos, • Minimalism Charanguista Viejo • Contemporary Silvestre Revueltas: Sensemayá • Latin Heritage Composers • Live Discussion with Scott Foglesong, Young Benjamin Britten: War Requiem, In Paradisum American Composer-in-Residence Viet Cuong, and Donato Cabrera Donato Cabrera, music director – Scott Foglesong, instructor – Sunshine Defner, sr. director of education. -

Representing Classical Music to Children and Young People in the United States: Critical Histories and New Approaches

REPRESENTING CLASSICAL MUSIC TO CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE IN THE UNITED STATES: CRITICAL HISTORIES AND NEW APPROACHES Sarah Elizabeth Tomlinson A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Chérie Rivers Ndaliko Andrea F. Bohlman Annegret Fauser David Garcia Roe-Min Kok © 2020 Sarah Elizabeth Tomlinson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Sarah Elizabeth Tomlinson: Representing Classical Music to Children and Young People in the United States: Critical Histories and New Approaches (Under the direction of Chérie Rivers Ndaliko) In this dissertation, I analyze the history and current practice of classical music programming for youth audiences in the United States. My examination of influential historical programs, including NBC radio’s 1928–42 Music Appreciation Hour and CBS television’s 1958–72 Young People’s Concerts, as well as contemporary materials including children’s visual media and North Carolina Symphony Education Concerts from 2017–19, show how dominant representations of classical music curated for children systemically erase women and composers- of-color’s contributions and/or do not contextualize their marginalization. I also intervene in how classical music is represented to children and young people. From 2017 to 2019, I conducted participatory research at the Global Scholars Academy (GSA), a K-8 public charter school in Durham, NC, to generate new curricula and materials fostering critical engagement with classical music and music history. Stemming from the participatory research principle of situating community collaborators as co-producers of knowledge, conducting participatory research with children urged me to prioritize children’s perspectives throughout this project. -

Homenaje a García Lorca, a Conductor's Approach

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2015 Homenaje a García Lorca, A Conductor’s Approach Alejandro Artemio Larumbe Martínez Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Larumbe Martínez, Alejandro Artemio, "Homenaje a García Lorca, A Conductor’s Approach" (2015). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 4012. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/4012 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. HOMENAJE A GARCÍA LORCA, A CONDUCTOR’S APPROACH A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Alejandro A. Larumbe Martínez B.M., Florida International University, 2010 M.M., Louisiana State University, 2012 May 2016 Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank my family. To my father, who perhaps unknowingly developed my passion for music. He played for me countless hours of classical music recordings (opera specially), nurturing my love to music. I would like to thank my mother as well for driving me to every lesson, class, concert, and recital. For teaching me that one must always finish what one started. For pushing me to be a better person. Both have given me the moral, emotional, and financial support to finish my education. -

TANGLEWOOD ^Js M

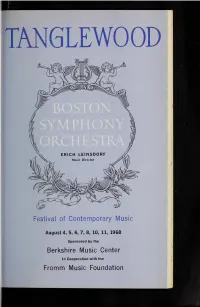

TANGLEWOOD ^jS m ram? ' I'' Festival of Contemporary Music August 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 1968 Sponsored by the Berkshire Music Center In Cooperation with the Fromm Music Foundation What tomorrow Sa Be Li sounds like Ai M D Ei B: M Red Seal Albums Available Today Pi ELLIOTT CARTER: PIANO CONCERTO ^ML V< Lateiner, pianist * - ~t ^v, M Jaeob World Premiere Recorded Live M at Symphony Hall, Bostoe X MICHAEL C0L6RASS: AS QUIET AS CI GINASTERA ^ BOSTON SYMPHONY ERICH LEINSDORF * M Concerto for Piano and Orchest ra Steffi! *^^l !***" Br Variaciones Concertantes (1961) (Me^mdem^J&K^irai .55*4 EH Joao Carlos Martins. Pianist Bit* Ei Boston Symphony, ZTAcjlititcvicU o/'Oic/>e*tia& Erich Pa Leinsdori, Conductor St X; ''?£x£ k M Pa gir ' H ** IF ^^P^ V3 SEIJI OZAWA H at) STRAVINSKY wa Victor 5«sp JBT jaVicruit ; M AGON TURANGAlilA SYMPHONY SCHULLER k TAKEMITSU jKiWiB ^NOVEMBER 5TEP5^ 7 STUDIES on THEMES of PAUL KLEE Bk (First recording] . jn BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA/ERICH LEINSDORF Wk. TORONTO Jm IV SYMPHONY^ ' ; Bfc* - * ^BIM ^JTeg X flititj g^M^HiH WKMi&aXi&i&X W Wt wnm :> ;.w%jii%. fl^B^^ ar ill THE VIRTUOSO SOUND of the ggS music pl CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA fornette JEAN MARTINON conductor fa coleman forms and sounds (recorded VARESE: ARCANA ' u live) as performed by the A. MARTIN: concerto for seven wind Philadelphia woodwind V quintet with interludes byornett* 198 INSTRUMENTS, TIMPANI, PERCUSSION m \ coleman SdilltS and ANO STRING ORCHESTRA Vsoldiers/space flight c \ ^mber { \ symphony of , I • 1 l _\. Philadelphia i-l.