1 the African Storybook and Language Teacher Identity In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloading As Pdfs (Print-Ready New Translations and Adaptations of Any Storybook

PAN-AFRICAN nxiety about technology is nothing new among Atraditional intellectuals. The Greek philosopher Plato worried that ©Shutterstock.com writing would produce forgetfulness – if you can write things down there is no need to remember them – while the English poet Alexander Pope described the invention of printing as a ‘scourge for the sins of the learned.’ Narratives about literature being shunted aside by other media go back to the advent of visual media such as movies or television, long before the rise of the internet. Digital media, Then as now, the view of a present where deep thinking and reading are literacies and relegated to the margins of cultural life by new technologies is overstated. African literature Firstly because reading, and especially the reading of high literary forms, has always been an activity for a minority In this article, we explore the impact of digital with a particular set of literacy skills, media on African literacy practices and surplus money and the leisure time literature. As our starting point, we want to to pursue it. As US media scholar Kathleen Fitzpatrick notes, narratives problematise the notion that digital media of cultural decay have more or less spell doom for reading generally and for overt ideological motivations. The African literature in particular. Versions of this subtext of recent statements about argument include perturbations that ‘African the decline of a reading culture in readerships are under siege’ by ‘the cost of the age of digital and social media is usually something like: ‘No one reads books, varying degrees of general literacy, [anything (I think is) good] anymore’ inadequate library services and the seductions (Fitzpatrick, 2012, p. -

Provider Readiness to Offer Programmes

African Storybook Guides Using African Storybooks with children The activities and resources on these pages have been tried by our education partners or ourselves when using African Storybooks with children. They include oral work with storybooks, asking questions and working with new words, linking reading and writing activities, talking about storybook pictures, and lots of ideas from successful reading lessons. We also give a detailed example of how to use African Storybooks for literacy activities in a multi-grade classroom with children of different ages. See also the other guides in this series: Preparing to use African Storybooks with children Developing, translating and adapting African Storybooks Using African Storybooks with children Contents Activity 1: Preparing to use an African Storybook with children .................................... 1 Resource 1: Types of reading activities ........................................................................... 1 Activity 2: Re-telling the story ......................................................................................... 2 Activity 3: Making your own colour copies of printed books.......................................... 3 Activity 4: Learning from other teachers ........................................................................ 3 Resource 2: Learning from our experiences .................................................................... 5 Activity 5: Talking about pictures ................................................................................... -

1 the African Storybook, Multilingual Literacy, and Social Change

The African Storybook, multilingual literacy, and social change in Ugandan classrooms Bonny Norton (UBC) and Juliet Tembe (Saide) In press: Applied Linguistics Review. Abstract For over a decade, the authors have worked collaboratively to better understand and address the challenges and possibilities of promoting multilingual literacy in Uganda, which has over 40 African languages, and where English is the official language. We begin the paper with a description of our current work on the African Storybook, a groundbreaking initiative of the South African Institute for Distance Education (Saide), which is promoting multilingual literacy for African children through the provision of hundreds of open-access stories on a powerful interactive website (www.africanstorybook.org). We draw on data from two Ugandan classrooms, one rural and one urban, to illustrate the challenges Ugandan teachers face in promoting literacy in both the mother tongue and English. We analyse the data with reference to the possibilities provided by the African Storybook website, focusing on mother tongue as resource, multimodality, translanguaging, and classroom management. We then draw on a 2015 teacher education workshop in eastern Uganda, as well as Darvin and Norton’s (2015) model of identity and investment, to illustrate how the African Storybook can help Ugandan teachers navigate classroom challenges and build on existing innovative practices. We conclude that the African Storybook can help implement the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. 1 Introduction We were not trained to teach reading and writing in Lunyole yet we are now forced to teach these skills in the mother tongue … They tell us instead to make our level best and yet there are no textbooks, not trained, so we just gamble. -

CV March 2020

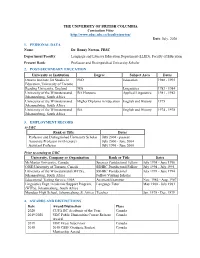

THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Curriculum Vitae http://www.educ.ubc.ca/faculty/norton/ Date: July, 2020 1. PERSONAL DATA Name: Dr. Bonny Norton, FRSC Department/Faculty: Language and Literacy Education Department (LLED), Faculty of Education Present Rank: Professor and Distinguished University Scholar 2. POST-SECONDARY EDUCATION University or Institution Degree Subject Area Dates Ontario Institute for Studies in PhD Education 1988 - 1993 Education, University of Toronto Reading University, England MA Linguistics 1983 - 1984 University of the Witwatersrand, BA Honours Applied Linguistics 1981 - 1982 Johannesburg, South Africa University of the Witwatersrand, Higher Diploma in Education English and History 1979 Johannesburg, South Africa University of the Witwatersrand, BA English and History 1974 - 1978 Johannesburg, South Africa 3. EMPLOYMENT RECORD At UBC Rank or Title Dates Professor and Distinguished University Scholar July 2004 - present Associate Professor (with tenure) July 2000 - June 2004 Assistant Professor July 1996 - June 2000 Prior to coming to UBC University, Company or Organization Rank or Title Dates McMaster University, Canada Spencer Postdoctoral Fellow July 1995 - June 1996 OISE/University of Toronto, Canada SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow July 1994 - July 1995 University of the Witwatersrand (WITS), SSHRC Postdoctoral July 1993 - June 1994 Johannesburg, South Africa Fellow/Visiting Scholar Educational Testing Service, USA Assistant Examiner Nov. 1984 - Aug. 1987 Linguistics Dept./Academic Support Program, Language Tutor -

The African Storybook and Teacher Identity

THE AFRICAN STORYBOOK AND TEACHER IDENTITY by Espen Stranger-Johannessen A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Language & Literacy Education) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2017 © Espen Stranger-Johannessen, 2017 Abstract The African Storybook (ASb) is a digital initiative that promotes multilingual literacy for African children by providing openly licenced children’s stories in multiple African languages, as well as English, French, and Portuguese. One of the ASb pilot sites, a primary school in Uganda, served as the focal case in this research, while two other schools and libraries were also included. Data was collected from June to December 2014 in the form of field notes, classroom observations, interview transcripts, and questionnaires, which were coded using retroductive coding. Based on Darvin and Norton’s (2015) model of identity and investment, and drawing on the Douglas Fir Group’s (2016) framework for second language acquisition, this study investigates Ugandan primary school teachers’ investment in the ASb and how their identities change through the process of using the stories and technology provided by the ASb. The findings indicate that the use of stories expands the repertoire of teaching methods and topics, and that this use is influenced by teachers’ social capital as well as financial factors and policies. Through the ASb initiative and its stories, the teachers began to imagine themselves as writers and translators; change agents; multimodal, multiliterate educators; and digital educators, reframing what it means to be a reading teacher. Teachers’ shifts of identity were indexical of their enhanced social and cultural capital as they engaged with the ASb, notwithstanding ideological constraints associated with mother tongue usage, assessment practices, and teacher supervision. -

African Storybook Initiative to Content Development for Multilingual Literacy Development in Africa

The contribution of the African Storybook initiative to content development for multilingual literacy development in Africa PALFA 2017, Abuja Presenters • Dorcas Wepukhulu (Partner Development Coordinator for the African Storybook initiative) • Dr John Ng’asike (Mount Kenya University, Thika) • Dr Cornelius Gulere (Uganda Christian University) • Tessa Welch (African Storybook Project Leader) African Storybook • An initiative of Saide (a South African NGO involved in open education projects across sub-Saharan Africa). • Addressing the question: “How can children learn to read without books? It’s like trying to learn soccer without a ball.” • Funded by Comic Relief since 2013, but now diversifying its funding strategy – Comic Relief 1/5th; other funders/projects 4/5ths. ASb publishing model Provides digital open access to children’s picture storybooks, with creation and translation tools for users to create and publish their own storybooks. A publishing solution ASb storybooks are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY 4.0) licence. You are free to download, copy, translate or adapt this story and use the illustrations as long as you attribute or credit the original author/s and illustrator/s. ASb’s main achievement 2013 to 2017 An African initiative by African people: almost all storybooks written by the African communities that use the storybooks. Story development workshops with educators and partner organizations where storybooks with local content are produced Rwanda Ghana Expansion into new countries Ethiopia Zambia Ethiopia -

Provider Readiness to Offer Programmes

African Storybook Guides Developing, translating and adapting African Storybooks There are different ways of making storybooks for the African Storybook website. You can translate or adapt a storybook, and publish a new version of that storybook. You can develop and create your own storybooks. We share some ideas that have helped us to develop storybooks, as well as what we have learned about translation and adaptation. See also the other guides in this series: Preparing to use African Storybooks with children Using African Storybooks with children 1 Developing, translating and adapting African Storybooks Contents Developing stories .............................................................................................................................. 1 Activity 1: What kinds of stories do children enjoy? ............................................................. 1 Activity 2: Different ways of developing stories .................................................................... 2 Idea 1: Drama and role-play ..................................................................................................... 2 Idea 2: Developing stories from your childhood experiences ............................................. 2 Idea 3: Developing stories from pictures ................................................................................ 2 Idea 4: Developing stories that relate to most primary school curricula ........................... 4 Idea 5: Gathering stories from elders in the community .................................................... -

African Storybook Initiative

“When I express myself in the language of my heart I’m sure of what is coming out. Their hearts – their culture - is being opened up by reading these stories so they find they are going much deeper in their learning. This is what the African Storybook helps us do.” African Storybook Initiative External ‘accountability’ evaluation: 2013 - 2016 John Gultig 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 5 Summary of the summary ............................................................................................................................... 5 The longer summary ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Overview .............................................................................................................................................. 20 The Project ..................................................................................................................................................... 20 The Evaluation ............................................................................................................................................... 21 1. Purpose .................................................................................................................................... 21 2. The evaluation questions.......................................................................................................... -

Preparing to Use African Storybooks with Children

African Storybook Guides Preparing to use African Storybooks with children The activities and resources on these pages are designed to help you explore the growing African Storybook website collection of storybooks, with your children in mind. We share with you our ideas of what a good storybook is, and how African Storybook educators have selected storybooks with a particular purpose and group of children. We also give examples of ways to access and read the storybooks with children – digitally or in print. See also the other guides in this series: Developing, translating and adapting African Storybooks Using African Storybooks with children Preparing to use African Storybooks with children Contents Activity 1: Choosing storybooks for children .................................................................. 1 Resource 1: What children need when learning to read................................................. 4 Activity 2: A ‘good’ storybook for children...................................................................... 5 Resource 2: African Storybook 50 suggested storybooks (2017) .................................... 8 Activity 3: Focusing on African Storybook illustrators and illustrations ......................... 9 Resource 3: Using the illustrations in African Storybooks............................................. 11 Activity 4: Linking African Storybooks to the school curriculum ................................... 13 Activity 5: Printed or digital storybooks (or both)? ...................................................... -

Espen Stranger-Johannessen University of British Columbia [email protected]

The International Research Foundation for English Language Education Title of Project: The African Storybook and Teacher Identity Researcher: Espen Stranger-Johannessen University of British Columbia [email protected] Research Supervisor: Dr. Bonny Norton University of British Columbia Espen Stranger-Johannessen Final Report Motivation for the Research Literacy rates in early primary school remain low in Uganda, despite concerted efforts from the government and non-governmental organizations, including a new curriculum, universal primary education, and large projects to promote literacy (Piper, 2010). Government initiatives and NGO interventions include comprehensive efforts on in-service training, textbook development, local language orthography development, provision of supplementary readers, and collaboration with educational officials, including efforts to scale up interventions (e.g., Lucas, McEwan, Ngware, and Oketch, 2014; Mango Tree, n.d.; RTI International, n.d.). Like many other African countries, Uganda is a multilingual nation, which poses a challenge in providing educational materials and teacher training that can adequately meet curricular demands. Of the country’s 43 recognized languages (Government of Uganda, 1992), just over 30 languages are used for instructional purposes in schools (LABE, FAWEU, & UNATU, n.d.). In most of these languages, however, reading materials are scarce, and the titles that are available in bookstores are usually unaffordable to most people. Books in English are more prevalent, but they are similarly -

Activity Theory and Interactive Design for the African Storybook Initiative

Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia (2018) 27(3), 293-308 Activity Theory and Interactive Design for the African Storybook Initiative Alan Amory Saide and University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg South Africa [email protected] Abstract: This research is concerned with the development and evaluation of a redesign of the online and mobile app African Storybook initiative services that support the authoring and reading of openly licensed storybooks to support literacy development in Africa. This redesign was initiated after a review of the African storybook web site and presented an opportunity to align the sociocultural theory used by African Storybook researchers and design of interactive artifacts and environments. The redesign makes use of a number of cultural-historical activity theory principles, including: object of activity (obyekt an independent entity and predmet the imagined objective outcome), tool mediated and shared objects that are part of the third-generation activity system. Three primary activities were identified (read, author and research). The author activity, implemented as a shared object includes library, create, translate and adapt objects of activity. Each of these objects make use of a single design pattern that includes a list of items that can be sorted, searched and viewed. Results from usability testing sessions lead to a refined design and provided evidence that redesign addresses problems identified during the review. This research illustrated that the reading, authoring and research obyekts created by individuals support the outcome of a new storybook (predmet). Introduction The aim of the African Storybook (ASb) initiative is to support and promote literacy in the languages of Africa using digital storybooks made available through openly licensed digital storybooks distributed by means of web-based Internet and mobile app services. -

THE UNIVERSITY of BRITISH COLUMBIA Curriculum Vitae Date: September 2017 1

THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Curriculum Vitae http://www.educ.ubc.ca/faculty/norton/ Date: September 2017 1. PERSONAL DATA Name: Dr. Bonny Norton, FRSC Department/Faculty: Language and Literacy Education Department (LLED), Faculty of Education Present Rank: Professor and Distinguished University Scholar 2. POST-SECONDARY EDUCATION University or Institution Degree Subject Area Dates Ontario Institute for Studies in PhD Education 1988 - 1993 Education, University of Toronto Reading University, England MA Linguistics 1983 - 1984 University of the Witwatersrand, BA Honours Applied Linguistics 1981 - 1982 Johannesburg, South Africa University of the Witwatersrand, Higher Diploma in Education English and History 1979 Johannesburg, South Africa University of the Witwatersrand, BA English and History 1974 - 1978 Johannesburg, South Africa 3. EMPLOYMENT RECORD At UBC Rank or Title Dates Professor and Distinguished University Scholar July 2004 - present Associate Professor (with tenure) July 2000 - June 2004 Assistant Professor July 1996 - June 2000 Prior to coming to UBC University, Company or Organization Rank or Title Dates McMaster University, Canada Spencer Postdoctoral Fellow July 1995 - June 1996 OISE/University of Toronto, Canada SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow July 1994 - July 1995 University of the Witwatersrand (WITS), SSHRC Postdoctoral July 1993 - June 1994 Johannesburg, South Africa Fellow/Visiting Scholar Educational Testing Service, USA Assistant Examiner Nov. 1984 - Aug. 1987 Linguistics Dept./Academic Support Program, Language