Prince William Forest Park: an Administrative History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prince William Forest Park Comprehensive Trails Plan and Environmental Assessment Prince William County, Virginia

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Prince William Forest Park Comprehensive Trails Plan and Environmental Assessment Prince William County, Virginia PRINCE WILLIAM FOREST PARK COMPREHENSIVE TRAILS PLAN ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT MARCH 2019 Environmental Assessment Prince William Forest Park Comprehensive Trails Plan Prince William Forest Park Comprehensive Trails Plan and Environmental Assessment Contents Purpose and Need 1 Planning Issues and Concerns for Detail Analysis 1 Planning Issues and Concerns Dismissed from Further Analysis 2 Alternatives 10 Alternative A: No-Action 10 Alternative B: Action Alternative 10 Alternatives Considered but Dismissed 12 Affected Environment and Environmental Consequences 19 Historic Structures 20 Impacts of Alternative A: No-Action 23 Impacts of Alternatives B: Action Alternative 24 Cultural Landscapes 27 Impacts of Alternative A: No-Action 28 Impacts of Alternatives B: Action Alternative 28 Visitor Use and Experience 29 Impacts of Alternative A: No-Action 32 Impacts of Alternatives B: Action Alternative 32 Consultation and Coordination 35 List of Preparers and Contributors 36 Figure 1: Project Area and Regional Context 3 Figure 2: Action B Action Alternative 15 Figure 3: Action B Action Alternative – New Parking Area and Public Access Roads 16 Figure 4: Action B Action Alternative – Cabin Camp Accessible Trail Areas 17 Figure 5: Area of Potential Effect 21 Figure 6: Photos of Trails and Cabin Camps in PRWI 31 Table 1: Anticipated Cumulative Projects In and Around the Project Site 19 Table of Contents i Environmental Assessment Prince William Forest Park Comprehensive Trails Plan This page is intentionally left blank Table of Contents ii Environmental Assessment Prince William Forest Park Comprehensive Trails Plan PURPOSE AND NEED The National Park Service (NPS) is developing a Comprehensive Trails Plan for Prince William Forest Park (the proposed project). -

Quality of Water and Bottom Material in Breckenridge Reservoir, Virginia, September 2008 Through August 2009

Prepared in cooperation with U.S. Marine Corps, Quantico, Virginia Quality of Water and Bottom Material in Breckenridge Reservoir, Virginia, September 2008 through August 2009 Open-File Report 2011–1305 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover photograph. Breckenridge Reservoir, Quantico, Virginia. Quality of Water and Bottom Material in Breckenridge Reservoir, Virginia, September 2008 through August 2009 By R. Russell Lotspeich Prepared in cooperation with U.S. Marine Corps, Quantico, Virginia Open-File Report 2011–1305 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2012 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Lotspeich, R.R., 2012, Quality of water and bottom material in Breckenridge Reservoir, Virginia, September 2008 through August 2009: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2011–1305, 19 p., plus appendixes. -

Prince William County, Virginia and Incorporated Areas

VOLUME 1 OF 4 PRINCE WILLIAM COUNTY, VIRGINIA AND INCORPORATED AREAS COMMUNITY COMMUNITY NAME NUMBER DUMFRIES, TOWN OF 510120 HAYMARKET, TOWN OF 510121 MANASSAS, CITY OF 510122 MANASSAS PARK, CITY OF 510123 OCCOQUAN, TOWN OF 510124 PRINCE WILLIAM COUNTY, 510119 UNINCORPORATED AREAS QUANTICO, TOWN OF 510232 September 30, 2020 REVISED: TBD FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 51153CV001B Version Number 2.6.4.6 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 1 Page SECTION 1.0 – INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 The National Flood Insurance Program 1 1.2 Purpose of this Flood Insurance Study Report 2 1.3 Jurisdictions Included in the Flood Insurance Study Project 2 1.4 Considerations for using this Flood Insurance Study Report 4 SECTION 2.0 – FLOODPLAIN MANAGEMENT APPLICATIONS 16 2.1 Floodplain Boundaries 16 2.2 Floodways 31 2.3 Base Flood Elevations 32 2.4 Non-Encroachment Zones 33 2.5 Coastal Flood Hazard Areas 33 2.5.1 Water Elevations and the Effects of Waves 33 2.5.2 Floodplain Boundaries and BFEs for Coastal Areas 35 2.5.3 Coastal High Hazard Areas 35 2.5.4 Limit of Moderate Wave Action 37 SECTION 3.0 – INSURANCE APPLICATIONS 37 3.1 National Flood Insurance Program Insurance Zones 37 SECTION 4.0 – AREA STUDIED38 4.1 Basin Description 38 4.2 Principal Flood Problems 38 4.3 Non-Levee Flood Protection Measures 40 4.4 Levees 41 SECTION 5.0 – ENGINEERING METHODS 41 5.1 Hydrologic Analyses 42 5.2 Hydraulic Analyses 55 5.3 Coastal Analyses 71 5.3.1 Total Stillwater Elevations 72 5.3.2 Waves 74 5.3.3 Coastal Erosion 75 5.3.4 Wave Hazard Analyses 75 5.4 Alluvial Fan Analyses 79 SECTION -

Scheel Index

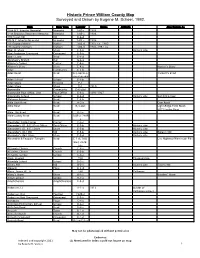

Historic Prince William County Map Surveyed and Drawn by Eugene M. Scheel, 1992. Item Item Type Locator Dates Altitude Also Known As 10th N.Y. Infantry Memorial Memorial 1stB-c 1906 14th Brooklyn Regiment Memorial Memorial 1stB-c 1906 190 Vision Hill Hill D-6-d 5th N.Y. Infantry Memorial Memorial 1stB-c 1906 7th Georgia Marker Marker 1stB-d 1905-ca. 1960 7th Georgia Markers Markers 1stB-d 1905-1987 ca. Abel, R. Store Store F-5-b Historic site Abel-Anderson Graveyard Graveyard F-5-b Abel's Lane Road E-4-d Abraham's Branch Run G-6-a ADams's Corner Corner E-4-a ADams's Store Store E-4-a Horton's Store Aden Community E-3-b Aden Road Road D-3-a&c;E-3- Tackett's Road a&b;E-4-a&b Aden School School E-3-b Aden Store Drawing E-1 Aden Store Store E-1 1910 Agnewville Community D-6-c&d Agnewville Post Office, 2nd Post Office E-6-a 1891-1927 Agnewville School School D-6-d Historic site Summit School Alabama Avenue Road E-6-b Aldie Dam Road Road A-2-a Dam Road Aldie Road Road B-3-a&c Light-Ridge Farm Road; H871Sudley Road Aldie, Old Road Road B-3-c Aldie-Sudley Road Road 1stB-a; 2ndB- a Alexander, Sadie Corner Corner C-3-c Alexander's (D. & E.) Post Office Post Office E-5-b Historic site Alexander's (D. & E.) Store Store E-5-b Historic site Alexander's (D.) Mill Mill E-5-b Historic site Bailey's Mill Alexander's (M.) Store Store E-5-d Historic site Alexandria & Fauquier Turnpike Road C-1-d; 1stB- Lee Highway/Warrenton Pike b&d; 2ndB- b&c All Saints Church Church C-4-c All Saints Church Church E-5-b All Saints School School C-4-c Allen, Howard ThU Thoroughfare Allendale School School D-3-c Allen's Mill Mill B-2-c Historic site Tyler's Mill Alpaugh Place D-4-d Alvey, James W., Jr. -

June 28, 2019 Fishing Report

COLORADO PARKS & WILDLIFE Fishing ReportFishing Regulations Friday June 28th, 2019 Review News and Information Upcoming Fishing Tournaments and Events Free Fishing Clinic at Boyd Lake State Park Saturday, June 29th all ages are welcome to Boyd’s Fishing Clinic. This class will be divided into two sessions with the first being geared towards kids and beginners. The second session will be geared more towards adults and intermediate anglers. We will have “loaner” fishing rods and basic tackle for those who do not have any gear. State and local agencies warn of the dangers present on Colorado’s rivers, streams, and lakes Following a strong winter and wet spring that overloaded the mountain snowpack, the statewide levels were 625 percent above the median. Jackson Lake State Park and CPW join national campaign to raises awareness of dangers associated with boating under the influence As part of the annual Operation Dry Water campaign, Jackson Lake State Park and Colorado Parks and Wildlife will join in the nationally coordinated effort to educate boaters about the dangers of boating while under the influence of alcohol or drugs. Take a Friend Fishing, Hook Great Prizes This year, CPW and our partner Colorado fishing companies are encouraging anglers to take a friend fishing. As a reward for sharing your expertise and love of fishing, we have created a contest for mentors who take the time to pass on their knowledge. Now you can take the #ColoradoOutdoors anywhere. Follow us on @instagram @coparkswildlife! http://instagram.com/coparkswildlife Check out our CPW community on Facebook. Colorado anglers can “like" the CPW Facebook page to get tips, share stories and more. -

Final 2022 WQA Guidance

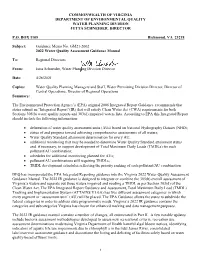

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY WATER PLANNING DIVISION JUTTA SCHNEIDER, DIRECTOR P.O. BOX 1105 Richmond, VA 23218 Subject: Guidance Memo No. GM21-2002 2022 Water Quality Assessment Guidance Manual To: Regional Directors From: Jutta Schneider, Water Planning Division Director Date: 4/26/2021 Copies: Water Quality Planning Managers and Staff, Water Permitting Division Director, Director of Central Operations, Director of Regional Operations Summary: The Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) original 2006 Integrated Report Guidance recommends that states submit an “Integrated Report”(IR) that will satisfy Clean Water Act (CWA) requirements for both Sections 305(b) water quality reports and 303(d) impaired waters lists. According to EPA this Integrated Report should include the following information: delineation of water quality assessment units (AUs) based on National Hydrography Dataset (NHD); status of and progress toward achieving comprehensive assessments of all waters; Water Quality Standard attainment determination for every AU; additional monitoring that may be needed to determine Water Quality Standard attainment status and, if necessary, to support development of Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs) for each pollutant/AU combination; schedules for additional monitoring planned for AUs; pollutant/AU combinations still requiring TMDLs; TMDL development schedules reflecting the priority ranking of each pollutant/AU combination. DEQ has incorporated the EPA Integrated Reporting guidance into the Virginia 2022 Water Quality Assessment Guidance Manual. The 2022 IR guidance is designed to integrate or combine the 305(b) overall assessment of Virginia’s waters and separate out those waters impaired and needing a TMDL as per Section 303(d) of the Clean Water Act. -

Hunting and Fishing Regulations (Draft)

UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS MARINE CORPS INSTALLATIONS NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION MARINE CORPS BASE QUANTIC0 3250 CATLIN AVENUNE QUANTICO, VIRGINIA 22134-5102 MCINCR-MCBQO 11015.2D B 046 11 January 2021 MARINE CORPS INSTALLATIONS NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION–MARINE CORPS BASE QUANTICO ORDER 11015.2D From: Commander To: Distribution List Subj: FISH AND WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT PROCEDURAL MANUAL Ref: (a) 16 U.S.C. 670, et seq. (b) MCO P5090.2 (c) DFAS-CL NAVSO P-1000 (d) MCO 7300.21B (e) 10 U.S.C. 2671 (f) 10 U.S.C. 1588 (g) MCINCR-MCBO 11015.3B (h) MCO 5090.4 (i) U.S. Marine Corps and U.S Fish and Wildlife Service Memorandum of Agreement (j) 16 U.S.C. 1531, et seq. (k) MCINCR-MCBO 5530.2 Encl: (1) FISH AND WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT PROCEDURAL MANUAL 1. Situation. To provide policy and procedural guidance for fish and wildlife management programs at Marine Corps Installations National Capital Region-Marine Corps Base Quantico (MCINCR-MCBQ), to include fishing, hunting, trapping, conservation law enforcement, wildlife viewing, animal damage control, and threatened and endangered species protection. 2. Cancellation. MCINCR-MCBQ P11015.2C. 3. Mission. It is the policy of the Commander MCINCR-MCBQ to promote a wildlife conservation program that shall be consistent with federal, Virginia (VA), and local laws and will support, as its foremost priority, the highest feasible quality of military training. The program will enhance to the extent feasible resource-related recreational opportunities subject to appropriate safety restrictions, security requirements, ecosystem management initiatives, animal damage control needs, and protection of threatened and endangered species. -

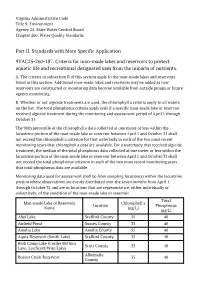

Part II. Standards with More Specific Application 9VAC25-260-187

Virginia Administrative Code Title 9. Environment Agency 25. State Water Control Board Chapter 260. Water Quality Standards Part II. Standards with More Specific Application 9VAC25-260-187. Criteria for man-made lakes and reservoirs to protect aquatic life and recreational designated uses from the impacts of nutrients. A. The criteria in subsection B of this section apply to the man-made lakes and reservoirs listed in this section. Additional man-made lakes and reservoirs may be added as new reservoirs are constructed or monitoring data become available from outside groups or future agency monitoring. B. Whether or not algicide treatments are used, the chlorophyll a criteria apply to all waters on the list. The total phosphorus criteria apply only if a specific man-made lake or reservoir received algicide treatment during the monitoring and assessment period of April 1 through October 31. The 90th percentile of the chlorophyll a data collected at one meter or less within the lacustrine portion of the man-made lake or reservoir between April 1 and October 31 shall not exceed the chlorophyll a criterion for that waterbody in each of the two most recent monitoring years that chlorophyll a data are available. For a waterbody that received algicide treatment, the median of the total phosphorus data collected at one meter or less within the lacustrine portion of the man-made lake or reservoir between April 1 and October 31 shall not exceed the total phosphorus criterion in each of the two most recent monitoring years that total phosphorus data are available. Monitoring data used for assessment shall be from sampling location(s) within the lacustrine portion where observations are evenly distributed over the seven months from April 1 through October 31 and are in locations that are representative, either individually or collectively, of the condition of the man-made lake or reservoir. -

Monitoring of Lakes and Reservoirs

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY WATER PLANNING DIVISION JUTTA SCHNEIDER, DIRECTOR P.O.BOX 1105 _______________________________________________________ Richmond, Virginia 23218 Subject: Guidance Memo No. 09-2005 Monitoring of Lakes and Reservoirs To: Regional Directors From: Jutta Schneider, Water Planning Division Director Date: October 26, 2020 Copies: Regional Water Quality Planning Managers and staff, Water Planning Division Managers, WMA Staff Summary: This guidance supersedes all agency Monitoring of Lakes and Reservoirs guidance prior to 2020 and provides direction to agency staff on how to implement lake/reservoir water quality monitoring. Significant updates to this guidance since 2002 include implementing the new surface water quality standard regulation (9 VAC 25-260-187), effective as of August 14, 2007, which added nutrient criteria for significant man-made lakes and reservoirs and the two natural lakes in Virginia. Triennial Review updates to 9 VAC 25-260-187 include the definition of lacustrine zone, which allows for dissolved oxygen sampling throughout the lake to determine thermal stratification and adds several additional lakes (8) to the significant lakes list. Updates to 9VAC25-260-50 include applying dissolved oxygen and pH criteria only to the epilimnion of thermally-stratified lakes listed in 9 VAC 25-260-187. In 2020, all references to lake/reservoir assessment methodology were moved to DEQ’s Water Quality Assessment Guidance Manual. Electronic Copy: Once effective, an electronic copy -

Marine Corps Combat Development Command (Mccdc) Quantico, Prince William County, Virginia Epa Facility Id: Va1170024722

FINAL RELEASE PUBLIC HEALTH ASSESSMENT MARINE CORPS COMBAT DEVELOPMENT COMMAND (MCCDC) QUANTICO, PRINCE WILLIAM COUNTY, VIRGINIA EPA FACILITY ID: VA1170024722 May 6, 2004 Prepared by: Federal Facilities Assessment Branch Division of Health Assessment and Consultation Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Final Release, MCCDC Quantico Foreword [INSERT] ii Final Release, MCCDC Quantico Table of Contents Foreword ................................................................................................................... ii List of Abbreviations ............................................................................................... vi I. Summary ............................................................................................................. 1 II. Background ........................................................................................................ 7 1. Site Description and Operational History ..................................................................... 7 2. Remedial and Regulatory History ................................................................................. 8 3. ATSDR Involvement .................................................................................................. 10 4. Demographics ............................................................................................................. 12 5. Land Use and Natural Resources ................................................................................ 13 6. Hydrogeology ............................................................................................................ -

2019 Fish Distribution Schedule

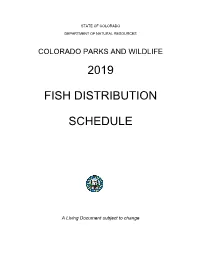

STATE OF COLORADO DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES COLORADO PARKS AND WILDLIFE 2019 FISH DISTRIBUTION SCHEDULE A Living Document subject to change SPECIES CODING FOR CPW FISH STOCKING SCHEDULE CODE SPECIES CODE SPECIES ARC ARCTIC CHAR RCH RIO GRANDE CHUB ARD ARKANSAS RIVER DARTER RGS RIO GRANDE SUCKER BCF CATFISH-BLUE RBT-ARR RAINBOW T - ARLEE BCR BLACK CRAPPIE RBT-BEL RAINBOW T - BELLAIRE BGL BLUEGILL RBT-RBF RAINBOW T - BROOD BHD BULLHEAD RBT-CRR RAINBOW T - COLO RIVER BRK BROOK TROUT RBT-ELR RAINBOW T - EAGLE LAKE CCF CATFISH-CHANNEL RBT-ERW RAINBOW T - ERWIN CHI CHINOOK SALMON RBT-GRR RAINBOW T - GUNNISON RIVER CRA CRAPPIE RBT-HOF RAINBOW T - HOFER CSH COMMON SHINER RBT-HXH RAINBOW T - HOFER X HARRISON CUT-CAR CUTTHROAT-CAR CREEK RBT-HXC RAINBOW THOFER X COLORADO RIVER RAINBOW CUT-CR1 CUTTHROAT-COLO RIVER "A" STRAIN RBT-HHC RAINBOW T - HOFER HARRISON CUTTHROAT CUT-CRN CUTTHROAT-COLO RIVER RBT-HHN RAINBOW T - HOFER HARRISON SNAKE RIVER CUT-GBN CUTTHROAT-GREEN BACK RBT-FLR RAINBOW T - FISH LAKE CUT-GBA CUTTHROAT-GREEN BACK -ARK. STRAIN RBT-RBM RAINBOW T - FEDERAL MITIGATION CUT-PPN CUTTHROAT-PIKES PEAK RBT-STH RAINBOW T - STEELHEAD CUT-RGN CUTTHROAT-RIO GRANDE RBT-HXG RAINBOW T - HOFER X GUNNISON RIVER CUT-RXN CUTTHROAT-RXC CROSS RBT-PRR RAINBOW T - PSYCHROPHILUM RESISTANT CUT-SRN CUTTHROAT-SNAKE RIVER RBT RAINBOW TROUT CUT-TRP CUTTHROAT-TRAPPER CREEK RSF SUNFISH - REDEAR CUT-WEM CUTTHROAT-WEMINUCHE RTC ROUNDTAIL CHUB CUT-YSN CUTTHROAT-McBRIDE (Yellowstone) SAG SAUGEYE CUT-NAN CUTTHROAT-NANITA SBS STRIPED BASS CUT-NAV CUTTHROAT-NAVAJO -

Commonwealth of Virginia Department of Environmental Quality Water Planning Division Jutta Schneider, Director

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY WATER PLANNING DIVISION JUTTA SCHNEIDER, DIRECTOR P.O.BOX 1105 ________________________________________________ Richmond, Virginia 23218 Subject: Guidance Memo No. 09-2005 Monitoring of Lakes and Reservoirs To: Regional Directors From: Jutta Schneider, Water Planning Division Director Date: October 26, 2020 Copies: Regional Water Quality Planning Managers and staff, Water Planning Division Managers, WMA Staff Summary: This guidance supersedes all agency Monitoring of Lakes and Reservoirs guidance prior to 2020 and provides direction to agency staff on how to implement lake/reservoir water quality monitoring. Significant updates to this guidance since 2002 include implementing the new surface water quality standard regulation (9 VAC 25-260-187), effective as of August 14, 2007, which added nutrient criteria for significant man- made lakes and reservoirs and the two natural lakes in Virginia. Triennial Review updates to 9 VAC 25- 260-187 included the definition of lacustrine zone, which allows for dissolved oxygen sampling throughout the lake to determine thermal stratification and adds several additional lakes (8) to the significant lakes list. Updates to 9VAC25-260-50 include applying dissolved oxygen and pH criteria apply only to the epilimnion of thermally-stratified lakes listed in 9 VAC 25-260-187. In 2020, all references to lake/reservoir assessment methodology were moved to DEQ’s Water Quality Assessment Guidance Manual. Electronic Copy: Once effective, an electronic copy