Foundation Document Prince William Forest Park Virginia December 2013 Foundation Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Potomac River. Days, Sundays, and National Holidays

§ 334.230 33 CFR Ch. II (7–1–12 Edition) (4) Day and night firing over the of the Naval Support Facility Dahl- range will be conducted intermittently gren, a distance of about 4,080 yards; by one or more vessels, depending on thence north along the Potomac shore weather and operating schedules. When of Naval Surface Warfare Center, Dahl- firing is in progress, adequate patrol by gren to Baber Point; and thence west naval craft will be conducted to pre- along the Upper Machodoc Creek shore vent vessels from entering or remain- of Naval Surface Warfare Center, Dahl- ing within the danger zone. gren to Howland Point at latitude (5) This section shall be enforced by 38°19′0.5″, longitude 77°03′23″; thence the Commandant, Fifth Naval District, northeast to latitude 38°19′18″, lon- U. S. Naval Base, Norfolk, Virginia, gitude 77°02′29″, a point on the Naval and such agencies as he may designate. Surface Warfare Center, Dahlgren [13 FR 6918, Nov. 24, 1948, as amended at 22 shore about 350 yards southeast of the FR 6965, Dec. 4, 1957. Redesignated at 50 FR base of the Navy recreational pier. Haz- 42696, Oct. 22, 1985] ardous operations are normally con- ducted in this zone daily except Satur- § 334.230 Potomac River. days, Sundays, and national holidays. (a) Naval Surface Warfare Center, (iii) Upper zone. Beginning at Mathias Dahlgren, VA—(1) The areas. Portions of Point, Va.; thence north to Light 5; the Upper Machodoc Creek and Poto- thence north-northeast to Light 6; mac River near Dahlgren, VA as de- thence east-southeast to Lighted Buoy scribed below: 2, thence east-southeast to a point on (i) Lower zone. -

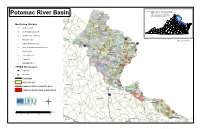

Potomac River Basin Assessment Overview

Sources: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality PL01 Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Virginia Department of Transportation Potomac River Basin Virginia Geographic Information Network PL03 PL04 United States Geological Survey PL05 Winchester PL02 Monitoring Stations PL12 Clarke PL16 Ambient (120) Frederick Loudoun PL15 PL11 PL20 Ambient/Biological (60) PL19 PL14 PL23 PL08 PL21 Ambient/Fish Tissue (4) PL10 PL18 PL17 *# 495 Biological (20) Warren PL07 PL13 PL22 ¨¦§ PL09 PL24 draft; clb 060320 PL06 PL42 Falls ChurchArlington jk Citizen Monitoring (35) PL45 395 PL25 ¨¦§ 66 k ¨¦§ PL43 Other Non-Agency Monitoring (14) PL31 PL30 PL26 Alexandria PL44 PL46 WX Federal (23) PL32 Manassas Park Fairfax PL35 PL34 Manassas PL29 PL27 PL28 Fish Tissue (15) Fauquier PL47 PL33 PL41 ^ Trend (47) Rappahannock PL36 Prince William PL48 PL38 ! PL49 A VDH-BEACH (1) PL40 PL37 PL51 PL50 VPDES Dischargers PL52 PL39 @A PL53 Industrial PL55 PL56 @A Municipal Culpeper PL54 PL57 Interstate PL59 Stafford PL58 Watersheds PL63 Madison PL60 Impaired Rivers and Streams PL62 PL61 Fredericksburg PL64 Impaired Reservoirs or Estuaries King George PL65 Orange 95 ¨¦§ PL66 Spotsylvania PL67 PL74 PL69 Westmoreland PL70 « Albemarle PL68 Caroline PL71 Miles Louisa Essex 0 5 10 20 30 Richmond PL72 PL73 Northumberland Hanover King and Queen Fluvanna Goochland King William Frederick Clarke Sources: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality Loudoun Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Virginia Department of Transportation Rappahannock River Basin -

A GUIDE to MCB QUANTICO WATERFOWL HUNTING Sixth Edition (2020)

A GUIDE TO MCB QUANTICO WATERFOWL HUNTING Sixth Edition (2020) Edited and Updated by Kenneth Erwin Fall 2020 Guide to MCB Quantico Waterfowl Hunting (2020) Table of Contents Introduction 3 Jump-Shooting 4 Chopawamsic Creek 4 Chopawamsic Creek Map 4 Blind 1 6 Blind 2 6 Blind 3 7 Blind 4 8 Blind 11 8 Blind A 9 Blind C 9 Quantico Creek 10 Blind 5 10 Blind 6 11 Blind 7 11 Blind 8 11 Blind E 12 Blind F 12 Blind Hospital Point 12 Potomac River 13 Potomac River Map 13 Blind D 14 Blind 9 14 Blind 10 15 MCAF Shoreline Restricted Area Map 16 Lunga Reservoir 17 Blind 12 17 Blind 13 17 Blind 14 18 Blind 15 18 Lunga Reservoir Map 19 Smith Lake 20 Blind 16 20 Blind 17 20 Smith Lake Map 20 Dalton Pond 21 Dalton Pond Blind 21 2 Guide to MCB Quantico Waterfowl Hunting (2020) INTRODUCTION This guide provides information about and directions to waterfowl blinds located aboard Marine Corps Base (MCB) Quantico. It also provides locations of the different boat launch points, information about the different waterways, and restrictions and safety concerns associated with the hunting areas. This guide is not an all-encompassing document but is a tool to assist you in getting safely to your hunting area. This document does not supersede MCB hunting regulations. For the purpose of this guide, the waterfowl blinds will be associated with the water feature where they are located. All directions will use the Game Check Station as the start point. -

Prince William Forest Park Comprehensive Trails Plan and Environmental Assessment Prince William County, Virginia

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Prince William Forest Park Comprehensive Trails Plan and Environmental Assessment Prince William County, Virginia PRINCE WILLIAM FOREST PARK COMPREHENSIVE TRAILS PLAN ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT MARCH 2019 Environmental Assessment Prince William Forest Park Comprehensive Trails Plan Prince William Forest Park Comprehensive Trails Plan and Environmental Assessment Contents Purpose and Need 1 Planning Issues and Concerns for Detail Analysis 1 Planning Issues and Concerns Dismissed from Further Analysis 2 Alternatives 10 Alternative A: No-Action 10 Alternative B: Action Alternative 10 Alternatives Considered but Dismissed 12 Affected Environment and Environmental Consequences 19 Historic Structures 20 Impacts of Alternative A: No-Action 23 Impacts of Alternatives B: Action Alternative 24 Cultural Landscapes 27 Impacts of Alternative A: No-Action 28 Impacts of Alternatives B: Action Alternative 28 Visitor Use and Experience 29 Impacts of Alternative A: No-Action 32 Impacts of Alternatives B: Action Alternative 32 Consultation and Coordination 35 List of Preparers and Contributors 36 Figure 1: Project Area and Regional Context 3 Figure 2: Action B Action Alternative 15 Figure 3: Action B Action Alternative – New Parking Area and Public Access Roads 16 Figure 4: Action B Action Alternative – Cabin Camp Accessible Trail Areas 17 Figure 5: Area of Potential Effect 21 Figure 6: Photos of Trails and Cabin Camps in PRWI 31 Table 1: Anticipated Cumulative Projects In and Around the Project Site 19 Table of Contents i Environmental Assessment Prince William Forest Park Comprehensive Trails Plan This page is intentionally left blank Table of Contents ii Environmental Assessment Prince William Forest Park Comprehensive Trails Plan PURPOSE AND NEED The National Park Service (NPS) is developing a Comprehensive Trails Plan for Prince William Forest Park (the proposed project). -

Quality of Water and Bottom Material in Breckenridge Reservoir, Virginia, September 2008 Through August 2009

Prepared in cooperation with U.S. Marine Corps, Quantico, Virginia Quality of Water and Bottom Material in Breckenridge Reservoir, Virginia, September 2008 through August 2009 Open-File Report 2011–1305 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover photograph. Breckenridge Reservoir, Quantico, Virginia. Quality of Water and Bottom Material in Breckenridge Reservoir, Virginia, September 2008 through August 2009 By R. Russell Lotspeich Prepared in cooperation with U.S. Marine Corps, Quantico, Virginia Open-File Report 2011–1305 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2012 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Lotspeich, R.R., 2012, Quality of water and bottom material in Breckenridge Reservoir, Virginia, September 2008 through August 2009: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2011–1305, 19 p., plus appendixes. -

County of Prince William 5 County Complex Court, Suite 290 Prince William, Virginia 22192-9201

X. NORTHERN VIRGINIA TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY M E M O R A N D U M TO: Chairman Martin E. Nohe and Members Northern Virginia Transportation Authority FROM: Monica Backmon, Executive Director DATE: September 6, 2018 SUBJECT: Executive Director’s Report ______________________________________________________________________________ 1. Purpose: To inform the Northern Virginia Transportation Authority (NVTA) of items of interest not addressed in other agenda items. 2. Project Status Updates With 78 executed Standard Project Agreements (SPAs) already in place, and another 44 SPAs set to follow through the recently adopted 2018-2023 Six Year Program, NVTA staff are in the process of enhancing their oversight and coordination activities. These enhanced activities will provide Authority members and others with greater insights regarding the status of projects funded with NVTA revenues (regional and local). Starting in fall 2018, jurisdictional and agency staff will periodically meet with and brief NVTA staff on the status of projects with approved SPAs. These briefings, which are expected to occur every 3-6 months, will include: schedule updates; project funding and SPA billings; risk identification and mitigation; upcoming milestones, including groundbreaking and ribbon-cuttings; and overview of major projects using local distribution (30%) revenues. Also starting in Fall 2018, NVTA staff will present a series of briefings to the Authority on project status and key trends in each of the region’s transportation corridors. The purpose of these briefings is to raise awareness of the Authority’s investments across the region. The first presentation is tentatively scheduled for the October meeting, will focus on the I-95/Route 1/VRE Fredericksburg Line corridor. -

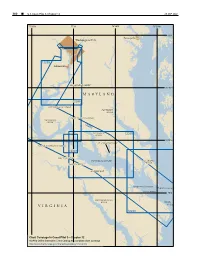

M a R Y L a N D V I R G I N

300 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 3, Chapter 12 26 SEP 2021 77°20'W 77°W 76°40'W 76°20'W 39°N Annapolis Washington D.C. 12289 Alexandria PISCATAWAY CREEK 38°40'N MARYLAND 12288 MATTAWOMAN CREEK PATUXENT RIVER PORT TOBACCO RIVER NANJEMOY CREEK 12285 WICOMICO 12286 RIVER 38°20'N ST. CLEMENTS BAY UPPER MACHODOC CREEK 12287 MATTOX CREEK POTOMAC RIVER ST. MARYS RIVER POPES CREEK NOMINI BAY YEOCOMICO RIVER Point Lookout COAN RIVER 38°N RAPPAHANNOCK RIVER Smith VIRGINIA Point 12233 Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 3—Chapter 12 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 3, Chapter 12 ¢ 301 Chesapeake Bay, Potomac River (1) This chapter describes the Potomac River and the above the mouth; thence the controlling depth through numerous tributaries that empty into it; included are the dredged cuts is about 18 feet to Hains Point. The Coan, St. Marys, Yeocomico, Wicomico and Anacostia channels are maintained at or near project depths. For Rivers. Also described are the ports of Washington, DC, detailed channel information and minimum depths as and Alexandria and several smaller ports and landings on reported by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), these waterways. use NOAA Electronic Navigational Charts. Surveys and (2) channel condition reports are available through a USACE COLREGS Demarcation Lines hydrographic survey website listed in Appendix A. (3) The lines established for Chesapeake Bay are (12) described in 33 CFR 80.510, chapter 2. Anchorages (13) Vessels bound up or down the river anchor anywhere (4) ENCs - US5VA22M, US5VA27M, US5MD41M, near the channel where the bottom is soft; vessels US5MD43M, US5MD44M, US4MD40M, US5MD40M sometimes anchor in Cornfield Harbor or St. -

Chopawamsic Creek

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 3-2011 Marine Corps Base, Quantico Shoreline Protection Plan Shoreline Studies Program, Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Recommended Citation Shoreline Studies Program, Virginia Institute of Marine Science. (2011) Marine Corps Base, Quantico Shoreline Protection Plan. Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary. https://doi.org/10.21220/V51436 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Marine Corps Base, Quantico Shoreline Protection Plan Shoreline Studies Program Virginia Institute of Marine Science College of William & Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia March 2011 Marine Corps Base, Quantico Shoreline Protection Plan Shoreline Studies Program Virginia Institute of Marine Science College of William & Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia Final Report March 2011 Table of Contents 7.1.2 Upland and Shore Zone Characteristics ...................................9 7.1.3 Nearshore Characteristics ..............................................9 7.2 Design Considerations and Recommendations ....................................9 Table of Contents....................................................................... i 8 Reach 4: North of the Marina -

![MCB Quantico Or Any 2011] Such Agencies He/She Designates](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5911/mcb-quantico-or-any-2011-such-agencies-he-she-designates-2825911.webp)

MCB Quantico Or Any 2011] Such Agencies He/She Designates

§ 334.235 33 CFR Ch. II (7–1–11 Edition) the area until convenient to the firing reflective material will be placed schedule to do so. across the Chopawamsic Creek channel at the entrance to the channel from [13 FR 6916, Nov. 24, 1948, as amended at 13 FR 9557, Dec. 31, 1948; 21 FR 2817, May 1, 1956; the Potomac River and immediately 22 FR 2951, Apr. 26, 1957; 28 FR 349, Jan. 12, west of the CSX railroad bridge. 1963; 48 FR 54597, Dec. 6, 1983. Redesignated (c) Enforcement. The regulations in at 50 FR 42696, Oct. 22, 1985, as amended at 62 this section shall be enforced by the FR 17552, Apr. 10, 1997; 76 FR 10523, Feb. 25, Commander, MCB Quantico or any 2011] such agencies he/she designates. The areas identified in paragraph (a) of this § 334.235 Potomac River, Marine Corps Base Quantico (MCB Quantico) in section will be monitored 24 hours a vicinity of Marine Corps Air Facil- day, 7 days a week. Any person or ves- ity (MCAF), restricted area. sel encroaching within the areas iden- (a) The area. All of the navigable tified in paragraph (a) of this section waters of the Potomac River extending will be directed to immediately leave approximately 500 meters from the the restricted area. Failure to do so high-water mark on the Eastern shore- could result in forceful removal and/or line of the MCAF, bounded by these co- criminal charges. ordinates (including the Chopawamsic (d) Exceptions. Commercial fisherman Creek channel, but excluding will be authorized controlled access to Chopawamsic Island): Beginning at the restricted area (with the exception latitude 38°29′34.04″ N, longitude of Chopawamisc Creek channel) after 077°18′22.4″ W (Point A); thence to lati- registering with MCB Quantico offi- tude 38°29′43.01″ N, longitude 077°18′4.1″ cials and following specific access noti- (Point B); thence to latitude 38°29′55.1″ fication procedures. -

Prince William County, Virginia and Incorporated Areas

VOLUME 1 OF 4 PRINCE WILLIAM COUNTY, VIRGINIA AND INCORPORATED AREAS COMMUNITY COMMUNITY NAME NUMBER DUMFRIES, TOWN OF 510120 HAYMARKET, TOWN OF 510121 MANASSAS, CITY OF 510122 MANASSAS PARK, CITY OF 510123 OCCOQUAN, TOWN OF 510124 PRINCE WILLIAM COUNTY, 510119 UNINCORPORATED AREAS QUANTICO, TOWN OF 510232 September 30, 2020 REVISED: TBD FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 51153CV001B Version Number 2.6.4.6 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 1 Page SECTION 1.0 – INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 The National Flood Insurance Program 1 1.2 Purpose of this Flood Insurance Study Report 2 1.3 Jurisdictions Included in the Flood Insurance Study Project 2 1.4 Considerations for using this Flood Insurance Study Report 4 SECTION 2.0 – FLOODPLAIN MANAGEMENT APPLICATIONS 16 2.1 Floodplain Boundaries 16 2.2 Floodways 31 2.3 Base Flood Elevations 32 2.4 Non-Encroachment Zones 33 2.5 Coastal Flood Hazard Areas 33 2.5.1 Water Elevations and the Effects of Waves 33 2.5.2 Floodplain Boundaries and BFEs for Coastal Areas 35 2.5.3 Coastal High Hazard Areas 35 2.5.4 Limit of Moderate Wave Action 37 SECTION 3.0 – INSURANCE APPLICATIONS 37 3.1 National Flood Insurance Program Insurance Zones 37 SECTION 4.0 – AREA STUDIED38 4.1 Basin Description 38 4.2 Principal Flood Problems 38 4.3 Non-Levee Flood Protection Measures 40 4.4 Levees 41 SECTION 5.0 – ENGINEERING METHODS 41 5.1 Hydrologic Analyses 42 5.2 Hydraulic Analyses 55 5.3 Coastal Analyses 71 5.3.1 Total Stillwater Elevations 72 5.3.2 Waves 74 5.3.3 Coastal Erosion 75 5.3.4 Wave Hazard Analyses 75 5.4 Alluvial Fan Analyses 79 SECTION -

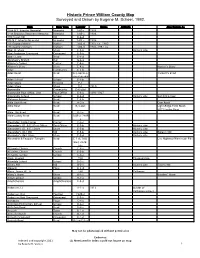

Scheel Index

Historic Prince William County Map Surveyed and Drawn by Eugene M. Scheel, 1992. Item Item Type Locator Dates Altitude Also Known As 10th N.Y. Infantry Memorial Memorial 1stB-c 1906 14th Brooklyn Regiment Memorial Memorial 1stB-c 1906 190 Vision Hill Hill D-6-d 5th N.Y. Infantry Memorial Memorial 1stB-c 1906 7th Georgia Marker Marker 1stB-d 1905-ca. 1960 7th Georgia Markers Markers 1stB-d 1905-1987 ca. Abel, R. Store Store F-5-b Historic site Abel-Anderson Graveyard Graveyard F-5-b Abel's Lane Road E-4-d Abraham's Branch Run G-6-a ADams's Corner Corner E-4-a ADams's Store Store E-4-a Horton's Store Aden Community E-3-b Aden Road Road D-3-a&c;E-3- Tackett's Road a&b;E-4-a&b Aden School School E-3-b Aden Store Drawing E-1 Aden Store Store E-1 1910 Agnewville Community D-6-c&d Agnewville Post Office, 2nd Post Office E-6-a 1891-1927 Agnewville School School D-6-d Historic site Summit School Alabama Avenue Road E-6-b Aldie Dam Road Road A-2-a Dam Road Aldie Road Road B-3-a&c Light-Ridge Farm Road; H871Sudley Road Aldie, Old Road Road B-3-c Aldie-Sudley Road Road 1stB-a; 2ndB- a Alexander, Sadie Corner Corner C-3-c Alexander's (D. & E.) Post Office Post Office E-5-b Historic site Alexander's (D. & E.) Store Store E-5-b Historic site Alexander's (D.) Mill Mill E-5-b Historic site Bailey's Mill Alexander's (M.) Store Store E-5-d Historic site Alexandria & Fauquier Turnpike Road C-1-d; 1stB- Lee Highway/Warrenton Pike b&d; 2ndB- b&c All Saints Church Church C-4-c All Saints Church Church E-5-b All Saints School School C-4-c Allen, Howard ThU Thoroughfare Allendale School School D-3-c Allen's Mill Mill B-2-c Historic site Tyler's Mill Alpaugh Place D-4-d Alvey, James W., Jr. -

Agenda Item #2 – Attachment 2, Transaction

V.B Transportation Action Plan for Northern Virginia TransAction Plan Project List Draft for Public Comment Spring/Summer 2017 This project list includes a brief Project List: Index by Corridor Segment description of the 358 candidate Segment Description Page regional projects included in 1-1 Rt. 7/Rt. 9 — West Virginia state line to Town of Leesburg 3 TransAction. The projects are 1-2 Rt. 7/Dulles Greenway — Town of Leesburg to Rt. 28 5 listed by Corridor Segment. 1-3 Rt. 7/Dulles Toll Road/Silver Line — Rt. 28 to Tysons 12 Larger projects are listed under 1-4 Rt. 7/Dulles Toll Road/Silver Line — Tysons to US 1 18 each Corridor Segment in which 2-1 Loudoun County Parkway/Belmont Ridge Road — Rt. 7 to US 50 36 they are located, and may 2-2 Bi-County Parkway — US 50 to I-66 42 appear multiple times in this 2-3 Rt. 234 — I-66 to I-95 45 project list. 3-1 Rt. 28 — Rt. 7 to I-66 51 3-2 Rt. 28 — I-66 to Fauquier County Line 56 4-1 Prince William Parkway — I-66 to I-95 60 5-1 Fairfax County Parkway — Rt. 7 to US 50 66 5-2 Fairfax County Parkway — US 50 to Rolling Road 70 5-3 Fairfax County Parkway — Rolling Road to US 1 74 6-1 I-66/US 29/VRE Manassas — Prince William County Line to Rt. 28 78 6-2 I-66/US 29/US 50/Orange Silver Line — Rt. 28 to I-495 84 6-3 I-66/US 29/US 50/Orange Silver Line — I-495 to Potomac River 90 7-1 I-495 — American Legion Bridge to I-66 100 7-2 I-495 — I-66 to I-395 105 7-3 I-495 — I-95 to Woodrow Wilson Bridge 110 I-95/US 1/VRE Fredericksburg — Stafford County Line to Fairfax County 8-1 121 Line 8-2 I-95/US 1/VRE Fredericksburg — Prince William County Line to I-495 127 I-395/US 1/VRE Fredericksburg/Blue Yellow Line — I-495 to Potomac 8-3 137 River 9-1 US 15 — Potomac River to Rt.