Final Report Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biodiversity Development Assessment Report Tweed Valley Hospital

92 Biodiversity Development Assessment Report Tweed Valley Hospital APPENDIX A. TWEED VALLEY HOSPITAL MASTERPLAN (DEVELOPMENT AND CONSTRUCTION FOOTPRINT) AND TWEED COAST ROAD DEVELOPMENT FOOTPRINT greencap.com.au Adelaide | Auckland | Brisbane | Canberra | Darwin | Melbourne | Newcastle | Perth | Sydney | Wollongong LEGEND 5 . 0 . 0 8 . 0 0 . 6 9 .0 SITE BOUNDARY 0 . 0 1 7 .0 MAXIMUM PLANNING 8.0 0 . 0 1 0 . ENVELOPE ABOVE 0 1 9.0 GROUND LEVEL 0 . 1 1 ENVIRONMENTAL AREA MAXIMUM PLANNING 0 . 2 1 ENVELOPE BELOW 0 . 0 E 1 0 . GROUND LEVEL N 3 I 1 0 . L 1 K 1 0 . N 4 RU 1 TREE TRUNK LINE T 0 . 5 E 1 RE 0 . T 6 0M 1 5 0 . APZ OFFSETS - 7 ) 1 06 0 . 0 8 (2 1 PROBABLE MAXIMUM Z T 0 P . 9 A - 67M 1 E 0 . FLOOD LINE 6 7) 0 1 . 0 2 E 201 0 . 1 T 2 0 . F 7 R A 1 AGRICULTURAL BUFFER 0 T . 2 (DR 2 Z 18.0 P S A INDICATIVE BUILDING K L 19.0 ENTRIES E C 0 V . LE 3 PMF 2 O 2 0.0 N R N 0 . 1 U 2 0 . 4 0 2 . 2 2 T .0 2 2 0 . 3 2 0 . 3 2 25.0 COPYRIGHT 2 3 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THIS WORK IS COPYRIGHT AND CANNOT BE .0 STAFF REPRODUCED OR COPIED IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY MEANS (GRAPHIC, ELECTRONIC OR MECHANICAL, INCLUDING PHOTOCOPYING) WITHOUT THE CARPARK 25 .0 WRITTEN PERMISSION OF THE PRINCIPAL UNDER THE TERMS OF THE CONTRACT. -

Bush Foods and Fibres

Australian Plants Society NORTH SHORE GROUP Ku-ring-gai Wildflower Garden Bush foods and fibres • Plant-based bush foods, medicines and poisons can come from nectar, flowers, fruit, leaves, bark, stems, sap and roots. • Plants provide fibres and materials for making many items including clothes, cords, musical instruments, shelters, tools, toys and weapons. • A fruit is the seed-bearing structure of a plant. • Do not eat fruits that you do not know to be safe to eat. Allergic reactions or other adverse reactions could occur. • We acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of this land and pay our respects to the Elders both past, present and future for they hold the memories, traditions, culture and hope of their people. Plants as food: many native plants must be processed before they are safe to eat. Flowers, nectar, pollen, Sugars, vitamins, honey, lerps (psyllid tents) minerals, starches, manna (e.g. Ribbon Gum proteins & other nutrients Eucalyptus viminalis exudate), gum (e.g. Acacia lerp manna decurrens) Fruit & seeds Staple foods Carbohydrates (sugars, starches, fibre), proteins, fats, vitamins Leaves, stalks, roots, apical Staple foods Carbohydrates, protein, buds minerals Plants such as daisies, lilies, orchids and vines Tubers, rhyzomes were a source of starchy tubers known as Carbohydrate, fibre, yams. The yam daisy Microseris lanceolata protein, vitamins, (Asteraceae) was widespread in inland NSW minerals and other states. The native yam Dioscorea transversa grows north from Stanwell Tops into Qld and Northern Territory and can be eaten raw or roasted as can those of Trachymene incisa. 1 Plant Description of food Other notes Acacia Wattle seed is a rich source of iron, Saponins and tannins and other essential elements. -

An Infrageneric Classification of Syzygium (Myrtaceae)

Blumea 55, 2010: 94–99 www.ingentaconnect.com/content/nhn/blumea RESEARCH ARTICLE doi:10.3767/000651910X499303 An infrageneric classification of Syzygium (Myrtaceae) L.A. Craven1, E. Biffin 1,2 Key words Abstract An infrageneric classification of Syzygium based upon evolutionary relationships as inferred from analyses of nuclear and plastid DNA sequence data, and supported by morphological evidence, is presented. Six subgenera Acmena and seven sections are recognised. An identification key is provided and names proposed for two species newly Acmenosperma transferred to Syzygium. classification molecular systematics Published on 16 April 2010 Myrtaceae Piliocalyx Syzygium INTRODUCTION foreseeable future. Yet there are many rewarding and worthy floristic and other scientific projects that await attention and are Syzygium Gaertn. is a large genus of Myrtaceae, occurring from feasible in the shorter time frame that is a feature of the current Africa eastwards to the Hawaiian Islands and from India and research philosophies of short-sighted institutions. southern China southwards to southeastern Australia and New One impediment to undertaking studies of natural groups of Zealand. In terms of species richness, the genus is centred in species of Syzygium, as opposed to floristic studies per se, Malesia but in terms of its basic evolutionary diversity it appears has been the lack of a framework or context within which a set to be centred in the Melanesian-Australian region. Its taxonomic of species can be the focus of specialised research. Below is history has been detailed in Schmid (1972), Craven (2001) and proposed an infrageneric classification based upon phylogenies Parnell et al. (2007) and will not be further elaborated here. -

Creating Jobs, Protecting Forests?

Creating Jobs, Protecting Forests? An Analysis of the State of the Nation’s Regional Forest Agreements Creating Jobs, Protecting Forests? An Analysis of the State of the Nation’s Regional Forest Agreements The Wilderness Society. 2020, Creating Jobs, Protecting Forests? The State of the Nation’s RFAs, The Wilderness Society, Melbourne, Australia Table of contents 4 Executive summary Printed on 100% recycled post-consumer waste paper 5 Key findings 6 Recommendations Copyright The Wilderness Society Ltd 7 List of abbreviations All material presented in this publication is protected by copyright. 8 Introduction First published September 2020. 9 1. Background and legal status 12 2. Success of the RFAs in achieving key outcomes Contact: [email protected] | 1800 030 641 | www.wilderness.org.au 12 2.1 Comprehensive, Adequate, Representative Reserve system 13 2.1.1 Design of the CAR Reserve System Cover image: Yarra Ranges, Victoria | mitchgreenphotos.com 14 2.1.2 Implementation of the CAR Reserve System 15 2.1.3 Management of the CAR Reserve System 16 2.2 Ecologically Sustainable Forest Management 16 2.2.1 Maintaining biodiversity 20 2.2.2 Contributing factors to biodiversity decline 21 2.3 Security for industry 22 2.3.1 Volume of logs harvested 25 2.3.2 Employment 25 2.3.3 Growth in the plantation sector of Australia’s wood products industry 27 2.3.4 Factors contributing to industry decline 28 2.4 Regard to relevant research and projects 28 2.5 Reviews 32 3. Ability of the RFAs to meet intended outcomes into the future 32 3.1 Climate change 32 3.1.1 The role of forests in climate change mitigation 32 3.1.2 Climate change impacts on conservation and native forestry 33 3.2 Biodiversity loss/resource decline 33 3.2.1 Altered fire regimes 34 3.2.2 Disease 35 3.2.3 Pest species 35 3.3 Competing forest uses and values 35 3.3.1 Water 35 3.3.2 Carbon credits 36 3.4 Changing industries, markets and societies 36 3.5 International and national agreements 37 3.6 Legal concerns 37 3.7 Findings 38 4. -

Myrtle Rust Transition to Management Group Meeting Minutes

Minutes Meeting Two of the Myrtle Rust Transition to Management Group Teleconference held on Tuesday 20 December, 2011 Attendees: Colin Grant, DAFF (Chair); Lois Ransom, DAFF; Mikael Hirsch, DAFF; Greg Fraser, PHA; Rod Turner, PHA; Sophie Peterson, PHA; Jenna Taylor, PHA (Secretariat); Sam Malfroy, PHA; Kareena Arthy, DEEDI; Suzy Perry, DEEDI; Jim Thompson, DEEDI; Satendra Kumar, NSW DPI. Apologies: Mike Ashton, DEEDI; Bruce Christie, NSW DPI. Item 1 – Welcome by the Chair Colin Grant welcomed the Members of the Myrtle Rust Transition to Management Group (MRTMG) to the teleconference and the Members introduced themselves and provided information on their role. The Chair reinforced the need for urgency in progressing objectives of the Myrtle Rust Transition to Management (MRT2M) Program and this was noted by all Members. Item 2 – Terms of Reference Terms of Reference for the MRTMG were discussed and it was agreed that PHA would develop a set of Terms of Reference similar to those being developed for the Asian Honey Bee Transition to Management Group. These will be circulated for approval. Item 3 – Governance Arrangements Membership The MRTMG will be comprised of the following: Colin Grant, DAFF (Primary member) Lois Ransom, DAFF (Secondary member) Greg Fraser, PHA (Primary member) Rod Turner, PHA (Secondary member) Kareena Arthy, DEEDI (Primary member) Mike Ashton, DEEDI (Secondary member) Bruce Christie, NSW DPI (Primary member) Satendra Kumar, NSW DPI (Secondary member) It was agreed that other people would be invited to attend the meetings as appropriate. Chair It was confirmed that Colin Grant will be the Chair of the MRTMG. Secretariat and Administration Support PHA will provide the Secretariat and administration support for the program. -

Friends of the Brisbane Botanic Gardens and Sherwood Arboretum Newsletter

GOVERNANCE § Funding priorities Exciting news came in January, with the arrival $75,000 donated by Brisbane City Council. We plan to use that money wisely to kick start operations that will also raise more money and gain more members. For ABN 20 607 589 873 example, our corporate branding, Connect – Promote - Protect website, social media contacts all need DELECTABLE PLANT TREASURE: to be put on a professional footing. Jim Sacred Lotus, ponds near Administration Building, at Dobbins has been magnanimous with Mt Coot-tha Botanic Garden (J Sim 5 March 2016). his pro bono graphics and media Lilygram design for us and we thank him for all CONTENTS: his help and patience. Paul Plant has come on board the Management Newsletter Governance ............................1 Committee and steering our New Members! .......................1 promotions and publicity efforts. Issue 2, March 2016 New Sources! .........................2 Annual General Meeting Bump the Funny Bone !! .......2 Let's be friends… We decided against that Special INSTAGRAM News ...............2 General Meeting in April and will CONTACTING f BBGSA WEBSITE news .....................2 Our Website focus on working as a team of initial FACEBOOK news..................2 Directors until we stage the first AGM www.fbbgsa.org.au Postcards ................................3 (Membership details here) in August. PLANTspeak ..........................4 Email History EXPOSÉ ...................5 Making things Happen [email protected] FoSA news .............................7 Now we have reached accord with MAIL ADDRESS OBBG news ............................8 Friends of Sherwood Arboretum, we f BBGSA, PO Box 39, MCBG Visitor Centre .......... 10 are forging ahead with events and Sherwood, Qld 4075. Volunteer Guides news ........ 11 activities. However, we still need May Events! ........................ -

Threatened Species of Wilsons and Coopers Creek

Listed below are species recorded from the project areas of Goonengerry Landcare and Wilsons Creek Huonbrook Landcare groups. Additional species are known from adjacent National Parks. E = Endangered V = Vulnerable BCA - Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 EPBC - Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 Threatened Species of Wilsons and Coopers Creek SOS - Saving our Species Scientific name Common name TSC Act status EPBC Act status SOS stream Wilsons Creek and Coopers Creek are tributaries of the Wilsons River on the Far North Coast of New South Wales. Within the South East Queensland Bioregion, the native flora and fauna of PLANTS this region are among the most diverse in Australia. In the catchment areas of the Wilsons and Corokia whiteana Corokia V V Keep watch Coopers Creek 50 threatened species of flora and fauna can be found and 2 endangered Davidsonia johnsonii Smooth Davidson's Plum E E Site managed ecological communities. Desmodium acanthocladum Thorny Pea V V Site managed What is a threatened species? Diploglottis campbellii Small-leaved Tamarind E E Site managed Plants and animals are assessed on the threats that face them and the level to which they are at Doryanthes palmeri Giant Spear Lily V Keep watch risk of extinction. If the risk is high they are listed in legislation and conservation actions are Drynaria rigidula Basket Fern E Partnership developed for their protection. There are almost 1000 animal and plant species at risk of Elaeocarpus williamsianus Hairy Quandong E E Site managed extinction in NSW. Endiandra hayesii Rusty Rose Walnut V V Data deficient A species is considered threatened if: Endiandra muelleri subsp. -

Species Selection Guidelines Tree Species Selection

Species selection guidelines Tree species selection This section of the plan provides guidance around the selection of species for use as street trees in the Sunshine Coast Council area and includes region-wide street tree palettes for specific functions and settings. More specific guidance on signature and natural character palettes and lists of trees suitable for use in residential streets for each of the region's 27 Local plan areas are contained within Part B – Street tree strategies of the plan. Street tree palettes will be periodically reviewed as an outcome of street tree trials, the development of new species varieties and cultivars, or the advent of new pest or disease threats that may alter the performance and reliability of currently listed species. The plan is to be used in association with the Sunshine Coast Council Open Space Landscape Infrastructure Manual where guidance for tree stock selection (in line with AS 2303–2018 Tree stock for landscape use) and tree planting and maintenance specifications can be found. For standard advanced tree planting detail, maintenance specifications and guidelines for the selection of tree stock see also the Sunshine Coast Open Space Landscape Infrastructure Manual – Embellishments – Planting Landscape). The manual's Plant Index contains a comprehensive list of all plant species deemed suitable for cultivation in Sunshine Coast amenity landscapes. For specific species information including expected dimensions and preferred growing conditions see Palettes – Planting – Planting index). 94 Sunshine Coast Street Tree Master Plan 2018 Part A Tree nomenclature Strategic outcomes The names of trees in this document follow the • Trees are selected by suitably qualified and International code of botanical nomenclature experienced practitioners (2012) with genus and species given, followed • Tree selection is locally responsive and by the plant's common name. -

Specified Protected Matters Impact Profiles (Including Risk Assessment)

Appendix F Specified Protected Matters impact profiles (including risk assessment) Roads and Maritime Services EPBC Act Strategic Assessment – Strategic Assessment Report 1. FA1 - Wetland-dependent fauna Species included (common name, scientific name) Listing SPRAT ID Australasian Bittern (Botaurus poiciloptilus) Endangered 1001 Oxleyan Pygmy Perch (Nannoperca oxleyana) Endangered 64468 Blue Mountains Water Skink (Eulamprus leuraensis) Endangered 59199 Yellow-spotted Tree Frog/Yellow-spotted Bell Frog (Litoria castanea) Endangered 1848 Giant Burrowing Frog (Heleioporus australicus) Vulnerable 1973 Booroolong Frog (Litoria booroolongensis) Endangered 1844 Littlejohns Tree Frog (Litoria littlejohni) Vulnerable 64733 1.1 Wetland-dependent fauna description Item Summary Description Found in the waters, riparian vegetation and associated wetland vegetation of a diversity of freshwater wetland habitats. B. poiciloptilus is a large, stocky, thick-necked heron-like bird with camouflage-like plumage growing up to 66-76 cm with a wingspan of 1050-1180 cm and feeds on freshwater crustacean, fish, insects, snakes, leaves and fruit. N. oxleyana is light brown to olive coloured freshwater fish with mottling and three to four patchy, dark brown bars extending from head to tail and a whitish belly growing up to 35-60 mm. This is a mobile species that is often observed individually or in pairs and sometimes in small groups but does not form schools and feed on aquatic insects and their larvae (Allen, 1989; McDowall, 1996). E. leuraensis is an insectivorous, medium-sized lizard growing to approximately 20 cm in length. This species has a relatively dark brown/black body when compared to other Eulamprus spp. Also has narrow yellow/bronze to white stripes along its length to beginning of the tail and continuing along the tail as a series of spots (LeBreton, 1996; Cogger, 2000). -

DAVIDSON PLUM Davidsonia Jerseyana; Davidsonia Pruriens

focus on DAVIDSON PLUM Davidsonia jerseyana; Davidsonia pruriens Part of an R&D program managed by the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation Overview Davidson plum is a brilliant coloured fruit, dark blue purple on the outside and a deep reddish-pink on the inside. It has a juicy pulp and sharp acidic taste that means it is not often eaten fresh. However, the tart flavour and deep colour lend the plums to many uses in food manufacturing industries for value-added products such as jams, chutneys, sauces and yoghurt. Davidson plum Source: New Crop Industries Handbook The use of Davidson plum is widely recognised throughout Indigenous culture, although documented There are two species of Davidson plum used primarily for commercial information is scarce. Following European settlement production. they were sometimes dipped in salt and sugar obtained The predominant species is D. jerseyana. The tree’s natural range is from the settlers, but more often eaten fresh. sub-tropical rainforest areas from around Ballina to the Tweed Valley in The early settlers, meanwhile, used Davidson plum for far northern New South Wales, and around 30 kilometres inland from the making jam and jelly as well as a full-flavoured, dry red coast. This suggests the optimum growing area. wine. The fruit of the D. jerseyana has trunk-bearing characteristics, which Davidson plum was first written about in 1879 when the lends well to hand-harvesting from ground level. species was listed as an ornamental plant in the British The other species, D. pruriens, has a natural range in the coastal and publication, Gardeners Chronicle. -

Myrtle Rust Reviewed the Impacts of the Invasive Plant Pathogen Austropuccinia Psidii on the Australian Environment R

Myrtle Rust reviewed The impacts of the invasive plant pathogen Austropuccinia psidii on the Australian environment R. O. Makinson 2018 DRAFT CRCPLANTbiosecurity CRCPLANTbiosecurity © Plant Biosecurity Cooperative Research Centre, 2018 ‘Myrtle Rust reviewed: the impacts of the invasive pathogen Austropuccinia psidii on the Australian environment’ is licenced by the Plant Biosecurity Cooperative Research Centre for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Australia licence. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ This Review provides background for the public consultation document ‘Myrtle Rust in Australia – a draft Action Plan’ available at www.apbsf.org.au Author contact details R.O. Makinson1,2 [email protected] 1Bob Makinson Consulting ABN 67 656 298 911 2The Australian Network for Plant Conservation Inc. Cite this publication as: Makinson RO (2018) Myrtle Rust reviewed: the impacts of the invasive pathogen Austropuccinia psidii on the Australian environment. Plant Biosecurity Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra. Front cover: Top: Spotted Gum (Corymbia maculata) infected with Myrtle Rust in glasshouse screening program, Geoff Pegg. Bottom: Melaleuca quinquenervia infected with Myrtle Rust, north-east NSW, Peter Entwistle This project was jointly funded through the Plant Biosecurity Cooperative Research Centre and the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program. The Plant Biosecurity CRC is established and supported under the Australian Government Cooperative Research Centres Program. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This review of the environmental impacts of Myrtle Rust in Australia is accompanied by an adjunct document, Myrtle Rust in Australia – a draft Action Plan. The Action Plan was developed in 2018 in consultation with experts, stakeholders and the public. The intent of the draft Action Plan is to provide a guiding framework for a specifically environmental dimension to Australia’s response to Myrtle Rust – that is, the conservation of native biodiversity at risk. -

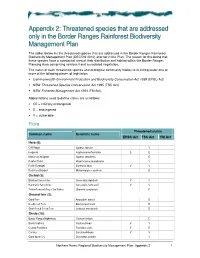

Appendix 2: Threatened Species That Are Addressed Only in the Border

Appendiix 2: Threatened speciies that are addressed only in the Border Ranges Raiinforest Biiodiversiity Management Pllan The tables below list the threatened species that are addressed in the Border Ranges Rainforest Biodiversity Management Plan (DECCW 2010) and not in this Plan. The reason for this being that these species have a substantial area of their distribution and habitat within the Border Ranges Planning Area comprising rainforest and associated vegetation. The status of each threatened species and ecological community relates to its listing under one or more of the following pieces of legislation: • Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) • NSW Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 (TSC Act) • NSW Fisheries Management Act 1994 (FM Act). Abbreviations used to define status are as follows: • CE = critically endangered • E = endangered • V = vulnerable Flora Threatened status Common name Scientific name EPBC Act TSC Act FM Act Herb (6): Cliff Sedge Cyperus rupicola V Isoglossa Isoglossa eranthemoides E E Missionary Nutgrass Cyperus semifertilis E Pointed Trefoil Rhynchosia acuminatissima V Pretty Eyebright Euphrasia bella V V Rock-face Bluebell Wahlenbergia scopulicola E Orchid (3): Blotched Sarcochilus Sarcochilus weinthalii V V Hartman's Sarcochilus Sarcochilus hartmannii V V Yellow-flowered King of the Fairies Oberonia complanata E Ground fern (3): Giant Fern Angiopteris evecta E Needle-leaf Fern Belvisia mucronata E Short-footed Screw Fern Lindsaea brachypoda E Shrub (16): Border Ranges Nightshade Solanum limitare E Brush Sophora Sophora fraseri V V Coastal Fontainea Fontainea oraria E E Corokia Corokia whiteana V V Giant Spear Lily Doryanthes palmeri V Northern Rivers Regional Biodiversity Management Plan: Appendix 2 1 Threatened status Common name Scientific name EPBC Act TSC Act FM Act Gympie Stinger Dendrocnide moroides E Jointed Baloghia Baloghia marmorata V V McPherson Range Pomaderris Pomaderris notata V Mt Merino Waxberry Gaultheria viridicarpa subsp.