8 Aviculture and Propagation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Control of Poultry Parasites

FAO Animal Health Manual No. 4 EPIDEMIOLOGY, DIAGNOSIS AND CONTROL OF POULTRY PARASITES Anders Permin Section for Parasitology Institute of Veterinary Microbiology The Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University Copenhagen, Denmark Jorgen W. Hansen FAO Animal Production and Health Division FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 1998 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. M-27 ISBN 92-5-104215-2 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Information Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy. C) FAO 1998 PREFACE Poultry products are one of the most important protein sources for man throughout the world and the poultry industry, particularly the commercial production systems have experienced a continuing growth during the last 20-30 years. The traditional extensive rural scavenging systems have not, however seen the same growth and are faced with serious management, nutritional and disease constraints. These include a number of parasites which are widely distributed in developing countries and contributing significantly to the low productivity of backyard flocks. -

Prevalence of Chlamydia Psittaci in Domesticated and Fancy Birds in Different Regions of District Faisalabad, Pakistan

United Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Research Article Prevalence of Chlamydia Psittaci in Domesticated and Fancy Birds in Different Regions of District Faisalabad, Pakistan Siraj I1, Rahman SU1, Ahsan Naveed1* Anjum Fr1, Hassan S2, Zahid Ali Tahir3 1Institute of Microbiology, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad 2Institute of Animal Nutrition and Feed Technology, University of Agriculture Faisalabad, Pakistan 3DiagnosticLaboraoty, Kamalia, Toba Tek Singh, Pakistan Volume 1 Issue 1- 2018 1. Abstract Received Date: 15 July 2018 1.1. Introduction Accepted Date: 31 Aug 2018 The study was aimed to check the prevalence of this zoonotic bacterium which is a great risk Published Date: 06 Sep 2018 towards human population in district Faisalabad at Pakistan. 1.2. Methodology 2. Key words Chlamydia Psittaci; Psittacosis; In present study, a total number of 259 samples including fecal swabs (187) and blood samples Prevalence; Zoonosis (72) from different aviculture of 259 birds such as chickens, ducks, pigeons, parrots, Australian parrots, and peacock were collected from different regions of Faisalabad, Pakistan. After process- ing the samples were inoculated in the yolk sac of embryonated chicken eggs for the cultivation ofChlamydia psittaci(C. psittaci)and later identified through Modified Gimenez staining and later CFT was performed for the determination of antibodies titer against C. psittaci. 1.3. Results The results of egg inoculation and modified Gimenez staining showed 9.75%, 29.62%, 10%, 36%, 44.64% and 39.28% prevalence in the fecal samples of chickens, ducks, peacocks, parrots, pi- geons and Australian parrots respectively. Accordingly, the results of CFT showed 15.38%, 25%, 46.42%, 36.36% and 25% in chickens, ducks, pigeons, parrots and peacock respectively. -

Protozoal Management in Turkey Production Elle Chadwick, Phd July

Protozoal Management in Turkey Production Elle Chadwick, PhD July 10, 2020 (updated) The two turkey protozoa that cause significant animal welfare and economic distress include various Eimeria species of coccidia and Histomonas meleagridis (McDougald, 1998). For coccidia, oral ingestion of the organism allows for colonization and replication while fecal shedding passes the organism to another host. With Histomonas, once one turkey is infected it can pass Histomonas to its flock mates by cloacal contact. Outbreaks of coccidiosis followed by Histomonosis (blackhead disease) is commonly seen in the field but the relationship between the protozoa is not understood. Turkey fecal moisture, intestinal health and behavior changes due to coccidiosis could be increasing horizontal transmission of Histomonas. Clinical signs of coccidiosis, like macroscopic lesions in the intestines, are not necessarily evident but altered weight gain and feed conversion are (Madden and Ruff, 1979; Milbradt et al., 2014). Birds can become more vocal. Depending on the infective dose, strain of coccidia and immune response of the turkey, intestinal irritation leading to diarrhea can occur (Chapman, 2008; McDougald, 2013). Birds are also more susceptible to other infectious agents. This is potentially due to the damage the coccidia can cause on the mucosal lining of the intestines but studies on this interaction are limited (Ruff et al., 1981; Milbradt et al., 2014). Coccidia sporozoites penetrate the turkey intestinal mucosa and utilize the intestinal tract for replication and survival. Of the seven coccidia Eimeria species known for infecting turkeys, four are considered pathogenic (E. adenoeides, E. gallopavonis, E. meleagrimitis and E. dispersa) (Chapman, 2008; McDougald, 2013; Milbradt et al., 2014). -

Alaska Legal Pet Guide Possession Import Take Comments

ALASKA LEGAL PET GUIDE POSSESSION IMPORT TAKE COMMENTS This is only a guide of animals that MAY be legal in a state. Due to the extensive amount of laws involved that are constantly changing, UAPPEAL and contributors of these guides cannot guarantee the accuracy of the information. Users are responsible for checking all laws BEFORE getting an animal. Legal as Pets as Legal Permit Register Pets for Legal Permit Pets for Legal ARACHNID, CENTIPEDE, MILLIPEDE All Yes No No Yes No Yes No known ADFG laws BATS Myotis, Keen's No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Myotis, Little Brown No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Silver-haired No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets All No No NA Live game - banned as pets BEARS Black No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Brown No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Polar No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets All No No NA Live game - no pets BIRDS Albatross, Black-footed No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Albatross, Short-tailed No No No State Endangered; Native species - banned as pets Ammoperdix (Genus) Yes Yes No Yes Yes NA Aviculture Permit needed to import or possess Canary Yes No No Yes NA Exempt Live Game - No ADFG permit needed; See Ag laws Capercaille Yes Yes No Yes Yes NA Aviculture Permit needed to import or possess Chickadee, Black-capped No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Chickadee, Boreal No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Chickadee, Chestnut-backed No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Chickadee, Gray-headed No No No Native/Live Game -

Blackhead Disease in Poultry Cecal Worms Carry the Protozoan That Causes This Disease

Integrated Pest Management Blackhead Disease in Poultry Cecal worms carry the protozoan that causes this disease By Dr. Mike Catangui, Ph.D., Entomologist/Parasitologist Manager, MWI Animal Health Technical Services In one of the most unique forms of disease transmissions known to biology, the cecal worm (Heterakis gallinarum) and the protozoan (Histomonas meleagridis) have been interacting with birds (mainly turkeys and broiler breeders) to perpetuate a serious disease called Blackhead (histomoniasis) in poultry. Also involved are earthworms and house flies that can transmit infected cecal worms to the host birds. Histomoniasis eventually results in fatal injuries to the liver of affected turkeys and chickens; the disease is also called enterohepatitis. Importance Blackhead disease of turkey was first documented in [Fig. 1] are parasites of turkeys, chickens and other the United States about 125 years ago in Rhode Island birds; Histomonas meleagridis probably just started as a (Cushman, 1893). It has since become a serious limiting parasite of cecal worms before it evolved into a parasite factor of poultry production in the U.S.; potential mortalities of turkey and other birds. in infected flocks can approach 100 percent in turkeys and 2. The eggs of the cecal worms (containing the histomonad 20 percent in chickens (McDougald, 2005). protozoan) are excreted by the infected bird into the poultry barn litter and other environment outside the Biology host; these infective cecal worm eggs are picked up by The biology of histomoniasis is quite complex as several ground-dwelling organisms such as earthworms, sow- species of organisms can be involved in the transmission, bugs, grasshoppers, and house flies. -

Scwds Briefs

SCWDS BRIEFS A Quarterly Newsletter from the Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study College of Veterinary Medicine The University of Georgia Phone (706) 542 - 1741 Athens, Georgia 30602 FAX (706) 542-5865 Volume 35 January 2020 Number 4 First report of HD in county 1980-1989 1990-1999 2000-2009 2010-2019 Figure 1. First reports of HD by state fish and wildlife agencies by decade from 1980 to 2019. Over most of this area, HD was rarely reported prior to 2000. Working Together: The 40th Anniversary of 1) sudden, unexplained, high mortality during the the National Hemorrhagic Disease Survey late summer and early fall; 2) necropsy diagnosis of HD as rendered by a trained wildlife biologist, a Forty years ago, in 1980, Dr. Victor Nettles diagnostician at a State Diagnostic Laboratory or launched an annual survey designed to document Veterinary College, or by SCWDS personnel; 3) and better understand the distribution and annual detection of epizootic hemorrhagic disease virus patterns of hemorrhagic disease (HD) in the (EHDV) or bluetongue virus (BTV) from an affected Southeast. Two years later (1982), this survey was animal; and 4) observation of hunter-killed deer that expanded to include the entire United States, and showed sloughing hooves, oral ulcers, or scars on its longevity and success can be attributed to a the rumen lining. These criteria, which have simple but informative design and the dedicated remained consistent during the entire 40 years, reporting of state fish and wildlife agency personnel. provide information on HD mortality and morbidity, During these 40 years, not a single state agency as well as validation of these clinical observations failed to report their annual HD activity. -

Biology of the Eared Grebe and Wilson's Phalarope in the Nonbreeding Season: a Study of Adaptations to Saline Lakes

BIOLOGY OF THE EAREDGREBEAND WILSONS’ PHALAROPE IN THE NONBREEDING SEASON: A STUDY OF ADAPTATIONS TO SALINE LAKES Joseph R. Jehl, Jr. Sea World Research Institute Hubbs Marine Research Center 1700 South Shores Road San Diego, California U.S.A. 92 109 Studies in Avian Biology No. 12 A PUBLICATION OF THE COOPER ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIEIY’ Cover Photograph: Eared Grebes (Podiceps nigricollis] at Mono Lake, California, October. 1985. Photograph by J. R. Jehl, Jr. i Edited by FRANK A. PITELKA at the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology University of California Berkeley, CA 94720 EDITORIAL ADVISORS FOR SAB 12 Ralph W. Schreiber Jared Verner David W. Winkler Studiesin Avian Biology is a series of works too long for The Condor, published at irregular intervals by the Cooper Ornithological Society. Manuscripts for con- sideration should be submitted to the current editor, Joseph R. Jehl, Jr., Sea World Research Institute, 1700 South Shores Road, San Diego, CA 92 109. Style and format should follow those of previous issues. Price: $14.00 including postage and handling. All orders cash in advance; make checks payable to Cooper Ornithological Society. Send orders to James R. North- ern, Assistant Treasurer, Cooper Ornithological Society, Department of Biology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90024. ISBN: O-935868-39-9 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 88-062658 Printed at Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas 66044 Issued 7 October 1988 Copyright by Cooper Ornithological Society, 1988 ii CONTENTS Abstract ............................. 1 Introduction ......................... 5 Eared Grebe ......................... 5 Methods ........................... 6 The Annual Cycle at Mono Lake ..... 8 Chronology ...................... 8 Composition of the population ..... 9 Size of the Mono Lake flock ...... -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

Review on Major Gastrointestinal Parasites That Affect Chickens

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3208 (Paper) ISSN 2225-093X (Online) Vol.6, No.11, 2016 Review on Major Gastrointestinal Parasites that Affect Chickens Abebe Belete* School of Veterinary Medicine, College of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine, Jimma University, P.O. Box: 307, Jimma, Ethiopia Mekonnen Addis School of Veterinary Medicine, College of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine, Jimma University, P.O. Box: 307, Jimma, Ethiopia Mihretu Ayele Department of animal health, Alage Agricultural TVET College, Ministry of Agriculture and Natural Resource, Ethiopia Abstract Parasitic diseases are among the major constraints of poultry production. The common internal parasitic infections occur in poultry include gastrointestinal helminthes (cestodes, nematodes) and Eimmeria species. Nematodes belong to the phylum Nemathelminthes, class Nematoda; whereas Tapeworms belong to the phylum Platyhelminthes, class Cestoda. Nematodes are the most common and most important helminth species and more than 50 species have been described in poultry; the majority of which cause pathological damage to the host.The life cycle of gastrointestinal nematodes of poultry may be direct or indirect but Cestodes have a typical indirect life cycle with one intermediate host. The life cycle of Eimmeria species starts with the ingestion of mature oocysts; and -

Lessons in Aviculture from English Aviaries (With Sixteen Illustrations)

THE CONDOR A BI-MONTHLY MAGAZINE OF WESTERN ORNITHOLOGY Published by the COOPER OBNITHOLOCICAL CLUB VOLUME XXVIII JANUARY-FEBRUARY, 1926 NUMBER 1 LESSONS IN AVICULTUKE FROM ENGLISH AVIARIES WITH SIXTEEN ILLUSTRATIONS By CASEY A. WOOD I. INTRODUCTION F,in the British Islands, tender, exotic birds can be kept alive in the open, and even induced to nest and raise families, how much more easily and with what I greater success ought their culture and study be pursued in lands more favored with warmth and sunshine. Among the numerous advantages that a subtropical climate offers for bird culture is economy in the erection and maintenance of shelters. Protection from severe weather involves some form of artificial heating, and when the outdoor aviary is built in a country with a wintry climate, punctuated by ice, snow _and cold fogs, these meteorologic conditions demand not only a substantial shelter, mvolving a considerable initial outlay, but added labor and expenseof upkeep. Hardy birds may come through a severe winter without fire, albeit they will probably not be comfortable; but delicate exotics will need stoves or central heating. Speaking of avian diseasesand of other obstacles to satisfactory aviculture in Great Britain, a well-known British aviarist remarks: “Great as are undoubtedly the natural difficulties of bird-keeping, I know of nothing more deadly than the English climate.” Yet, he might have added, England has been the home, par excellence, of bird culture for the past 300 years; and there are now more aviaries, rookeries, heronries and bird sanctuaries attached to English homes than can be found in any other country. -

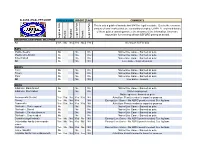

Model Aviculture Program an Overview of Map the Map Process Why Do We Need Map?

MODEL AVICULTURE PROGRAM P.O. Box 817, Oakley, CA 94561-0817 Phone: (925) 684-2244 Fax: (925) 684-2323 E-Mail: [email protected] Http://www.modelaviculture.org AN OVERVIEW OF MAP The Model Aviculture Program (MAP) was designed by aviculturists and avian veterinarians to improve avicultural practices through setting basic standards for avian husbandry. Individuals who apply to MAP are sent a sample Inspection Form and Guidelines to prepare for the inspection. Applicants select a veterinarian to do the inspection and inform MAP. The applicant is sent the official NCR Inspection Form and the veterinarian of their choice performs the inspection when the applicant sets up the appointment. MAP certification is provided for the individuals who meet MAP standards. MAP is not a private business; it is a non-profit service organization designed to be of benefit to aviculturists. Application fees are used for basic administrative costs. The clerical work is performed by one, part-time person. The management of MAP is under the direction of the MAP Board of Directors. The MAP Board is comprised of aviculturists experienced with a wide variety of bird species and of avian veterinarians. The MAP Board of Directors guides the organization and generates policies under which the certification program is administered. Many members of the present Board of Directors helped to design the program. In addition to the MAP Board, the organization is assisted by an Advisory Board of accomplished aviculturists and veterinarians from different geographical regions in the United States. THE MAP PROCESS People who write or call requesting an Application Form, receive a set of Guidelines and Instructions on how to prepare for the inspection process. -

REPRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOUR of the EARED GREBE, Podiceps Caspicus Nigricollis by NANCY MAHONEY Mcallister B.A., Oberlin College, 1954

REPRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOUR OF THE EARED GREBE, Podiceps caspicus nigricollis by NANCY MAHONEY McALLISTER B.A., Oberlin College, 1954 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OP THE REQUIREMENTS POR THE DEGREE OP MASTER OP ARTS in the Department of Zoology We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OP BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1955 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representative. It is under• stood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia, Vancouver 3, Canada. ii ABSTRACT The present study describes and analyses the elements involved in the reproductive behaviour of the Eared Grebe and the relationships between these elements. Two summers of observation and comparison with the published work on the Great Crested Grebe give some insight into these ele• ments, their evolution, and their stimuli. Threat and escape behaviour have been seen in the courtship of many birds, and the threat-escape theory of courtship in general has been derived from these cases. In the two grebes described threat plays a much less important role than the theory prescribes, and may not even be important at all. In the two patterns where the evolutionary relation• ships are clear, the elements are those of comfort preening.