A Further Review of the Problem of 'Escapes' M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NE Tibet, 2014

Mammals of NE Tibet, 28 July Ä 16 Aug 2014: An at-a-glance list of 26 species of mammals (& bird highlights).. By Jesper Hornskov ***this draft 23 Oct 2014*** ALL RIGHTS RESERVEDÄ Please note that the following list is best considered a work in progress. It should not be quoted without consulting the author. Based mostly on my own field notes, this brief write-up covers the mammals noted by J Clark, A Daws, M Hoit, J Jackson, S Lowe, H & P Schiermacker-Hansen, W Sterling, T Sykes, A Whitehouse & myself during a 2014 Oriental Bird Club Fundraiser visit to ChinaÄs Qinghai province. It was the 9th Oriental Bird Club Fundraiser trip in this area (another three have targeted desperately neglected Yunnan province, ChinaÄs biologically richest). This year we followed a slightly adjusted itinerary: as in the past we had allowed a good margin for altitude acclimatization & plenty of time to ensure that all specialities could be properly searched for. The mammals, the birds, the unbeatable scenery (at this time of the year in many places absolutely blanketed in wildflowers), an intriguing amalgam of local cultures, wonderful food, comfortable - from 'definitely OK' to 'surprisingly good' - accommodations & (not least) the companionship all came together to produce a trip the more memorable for the region - though in many ways an indisputable 'MUST' destination for anyone hooked on Palearctic and/or Asian mammals - being so under-visited. Anyone considering China as a natural history destination is welcome to contact the author at: Tel/fax +86 10 8490 9562 / NEW MOBILE +86 139 1124 0659 E-mail goodbirdmail(at)gmail.com or goodbirdmail(at)126.com Enquiries concerning future Oriental Bird Club Fundraisers - to NE Tibet, by and large following the itinerary used on the trip dealt with here, or Yunnan (our trips to ChinaÄs in every way most diverse province have been very popular) - can be made to Michael Edgecombe of the OBC at mail(at)orientalbirdclub.org or directly to this author. -

Prevalence of Chlamydia Psittaci in Domesticated and Fancy Birds in Different Regions of District Faisalabad, Pakistan

United Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Research Article Prevalence of Chlamydia Psittaci in Domesticated and Fancy Birds in Different Regions of District Faisalabad, Pakistan Siraj I1, Rahman SU1, Ahsan Naveed1* Anjum Fr1, Hassan S2, Zahid Ali Tahir3 1Institute of Microbiology, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad 2Institute of Animal Nutrition and Feed Technology, University of Agriculture Faisalabad, Pakistan 3DiagnosticLaboraoty, Kamalia, Toba Tek Singh, Pakistan Volume 1 Issue 1- 2018 1. Abstract Received Date: 15 July 2018 1.1. Introduction Accepted Date: 31 Aug 2018 The study was aimed to check the prevalence of this zoonotic bacterium which is a great risk Published Date: 06 Sep 2018 towards human population in district Faisalabad at Pakistan. 1.2. Methodology 2. Key words Chlamydia Psittaci; Psittacosis; In present study, a total number of 259 samples including fecal swabs (187) and blood samples Prevalence; Zoonosis (72) from different aviculture of 259 birds such as chickens, ducks, pigeons, parrots, Australian parrots, and peacock were collected from different regions of Faisalabad, Pakistan. After process- ing the samples were inoculated in the yolk sac of embryonated chicken eggs for the cultivation ofChlamydia psittaci(C. psittaci)and later identified through Modified Gimenez staining and later CFT was performed for the determination of antibodies titer against C. psittaci. 1.3. Results The results of egg inoculation and modified Gimenez staining showed 9.75%, 29.62%, 10%, 36%, 44.64% and 39.28% prevalence in the fecal samples of chickens, ducks, peacocks, parrots, pi- geons and Australian parrots respectively. Accordingly, the results of CFT showed 15.38%, 25%, 46.42%, 36.36% and 25% in chickens, ducks, pigeons, parrots and peacock respectively. -

Alaska Legal Pet Guide Possession Import Take Comments

ALASKA LEGAL PET GUIDE POSSESSION IMPORT TAKE COMMENTS This is only a guide of animals that MAY be legal in a state. Due to the extensive amount of laws involved that are constantly changing, UAPPEAL and contributors of these guides cannot guarantee the accuracy of the information. Users are responsible for checking all laws BEFORE getting an animal. Legal as Pets as Legal Permit Register Pets for Legal Permit Pets for Legal ARACHNID, CENTIPEDE, MILLIPEDE All Yes No No Yes No Yes No known ADFG laws BATS Myotis, Keen's No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Myotis, Little Brown No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Silver-haired No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets All No No NA Live game - banned as pets BEARS Black No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Brown No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Polar No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets All No No NA Live game - no pets BIRDS Albatross, Black-footed No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Albatross, Short-tailed No No No State Endangered; Native species - banned as pets Ammoperdix (Genus) Yes Yes No Yes Yes NA Aviculture Permit needed to import or possess Canary Yes No No Yes NA Exempt Live Game - No ADFG permit needed; See Ag laws Capercaille Yes Yes No Yes Yes NA Aviculture Permit needed to import or possess Chickadee, Black-capped No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Chickadee, Boreal No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Chickadee, Chestnut-backed No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Chickadee, Gray-headed No No No Native/Live Game -

Biology of the Eared Grebe and Wilson's Phalarope in the Nonbreeding Season: a Study of Adaptations to Saline Lakes

BIOLOGY OF THE EAREDGREBEAND WILSONS’ PHALAROPE IN THE NONBREEDING SEASON: A STUDY OF ADAPTATIONS TO SALINE LAKES Joseph R. Jehl, Jr. Sea World Research Institute Hubbs Marine Research Center 1700 South Shores Road San Diego, California U.S.A. 92 109 Studies in Avian Biology No. 12 A PUBLICATION OF THE COOPER ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIEIY’ Cover Photograph: Eared Grebes (Podiceps nigricollis] at Mono Lake, California, October. 1985. Photograph by J. R. Jehl, Jr. i Edited by FRANK A. PITELKA at the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology University of California Berkeley, CA 94720 EDITORIAL ADVISORS FOR SAB 12 Ralph W. Schreiber Jared Verner David W. Winkler Studiesin Avian Biology is a series of works too long for The Condor, published at irregular intervals by the Cooper Ornithological Society. Manuscripts for con- sideration should be submitted to the current editor, Joseph R. Jehl, Jr., Sea World Research Institute, 1700 South Shores Road, San Diego, CA 92 109. Style and format should follow those of previous issues. Price: $14.00 including postage and handling. All orders cash in advance; make checks payable to Cooper Ornithological Society. Send orders to James R. North- ern, Assistant Treasurer, Cooper Ornithological Society, Department of Biology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90024. ISBN: O-935868-39-9 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 88-062658 Printed at Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas 66044 Issued 7 October 1988 Copyright by Cooper Ornithological Society, 1988 ii CONTENTS Abstract ............................. 1 Introduction ......................... 5 Eared Grebe ......................... 5 Methods ........................... 6 The Annual Cycle at Mono Lake ..... 8 Chronology ...................... 8 Composition of the population ..... 9 Size of the Mono Lake flock ...... -

Assam Extension I 17Th to 21St March 2015 (5 Days)

Trip Report Assam Extension I 17th to 21st March 2015 (5 days) Greater Adjutant by Glen Valentine Tour leaders: Glen Valentine & Wayne Jones Trip report compiled by Glen Valentine Trip Report - RBT Assam Extension I 2015 2 Top 5 Birds for the Assam Extension as voted by tour participants: 1. Pied Falconet 4. Ibisbill 2. Greater Adjutant 5. Wedge-tailed Green Pigeon 3. White-winged Duck Honourable mentions: Slender-billed Vulture, Swamp Francolin & Slender-billed Babbler Tour Summary: Our adventure through the north-east Indian subcontinent began in the bustling city of Guwahati, the capital of Assam province in north-east India. We kicked off our birding with a short but extremely productive visit to the sprawling dump at the edge of town. Along the way we stopped for eye-catching, introductory species such as Coppersmith Barbet, Purple Sunbird and Striated Grassbird that showed well in the scopes, before arriving at the dump where large frolicking flocks of the endangered and range-restricted Greater Adjutant greeted us, along with hordes of Black Kites and Eastern Cattle Egrets. Eastern Jungle Crows were also in attendance as were White Indian One-horned Rhinoceros and Citrine Wagtails, Pied and Jungle Mynas and Brown Shrike. A Yellow Bittern that eventually showed very well in a small pond adjacent to the dump was a delightful bonus, while a short stroll deeper into the refuse yielded the last remaining target species in the form of good numbers of Lesser Adjutant. After our intimate experience with the sought- after adjutant storks it was time to continue our journey to the grassy plains, wetlands, forests and woodlands of the fabulous Kaziranga National Park, our destination for the next two nights. -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

Lessons in Aviculture from English Aviaries (With Sixteen Illustrations)

THE CONDOR A BI-MONTHLY MAGAZINE OF WESTERN ORNITHOLOGY Published by the COOPER OBNITHOLOCICAL CLUB VOLUME XXVIII JANUARY-FEBRUARY, 1926 NUMBER 1 LESSONS IN AVICULTUKE FROM ENGLISH AVIARIES WITH SIXTEEN ILLUSTRATIONS By CASEY A. WOOD I. INTRODUCTION F,in the British Islands, tender, exotic birds can be kept alive in the open, and even induced to nest and raise families, how much more easily and with what I greater success ought their culture and study be pursued in lands more favored with warmth and sunshine. Among the numerous advantages that a subtropical climate offers for bird culture is economy in the erection and maintenance of shelters. Protection from severe weather involves some form of artificial heating, and when the outdoor aviary is built in a country with a wintry climate, punctuated by ice, snow _and cold fogs, these meteorologic conditions demand not only a substantial shelter, mvolving a considerable initial outlay, but added labor and expenseof upkeep. Hardy birds may come through a severe winter without fire, albeit they will probably not be comfortable; but delicate exotics will need stoves or central heating. Speaking of avian diseasesand of other obstacles to satisfactory aviculture in Great Britain, a well-known British aviarist remarks: “Great as are undoubtedly the natural difficulties of bird-keeping, I know of nothing more deadly than the English climate.” Yet, he might have added, England has been the home, par excellence, of bird culture for the past 300 years; and there are now more aviaries, rookeries, heronries and bird sanctuaries attached to English homes than can be found in any other country. -

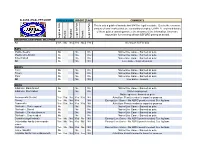

Model Aviculture Program an Overview of Map the Map Process Why Do We Need Map?

MODEL AVICULTURE PROGRAM P.O. Box 817, Oakley, CA 94561-0817 Phone: (925) 684-2244 Fax: (925) 684-2323 E-Mail: [email protected] Http://www.modelaviculture.org AN OVERVIEW OF MAP The Model Aviculture Program (MAP) was designed by aviculturists and avian veterinarians to improve avicultural practices through setting basic standards for avian husbandry. Individuals who apply to MAP are sent a sample Inspection Form and Guidelines to prepare for the inspection. Applicants select a veterinarian to do the inspection and inform MAP. The applicant is sent the official NCR Inspection Form and the veterinarian of their choice performs the inspection when the applicant sets up the appointment. MAP certification is provided for the individuals who meet MAP standards. MAP is not a private business; it is a non-profit service organization designed to be of benefit to aviculturists. Application fees are used for basic administrative costs. The clerical work is performed by one, part-time person. The management of MAP is under the direction of the MAP Board of Directors. The MAP Board is comprised of aviculturists experienced with a wide variety of bird species and of avian veterinarians. The MAP Board of Directors guides the organization and generates policies under which the certification program is administered. Many members of the present Board of Directors helped to design the program. In addition to the MAP Board, the organization is assisted by an Advisory Board of accomplished aviculturists and veterinarians from different geographical regions in the United States. THE MAP PROCESS People who write or call requesting an Application Form, receive a set of Guidelines and Instructions on how to prepare for the inspection process. -

REPRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOUR of the EARED GREBE, Podiceps Caspicus Nigricollis by NANCY MAHONEY Mcallister B.A., Oberlin College, 1954

REPRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOUR OF THE EARED GREBE, Podiceps caspicus nigricollis by NANCY MAHONEY McALLISTER B.A., Oberlin College, 1954 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OP THE REQUIREMENTS POR THE DEGREE OP MASTER OP ARTS in the Department of Zoology We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OP BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1955 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representative. It is under• stood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia, Vancouver 3, Canada. ii ABSTRACT The present study describes and analyses the elements involved in the reproductive behaviour of the Eared Grebe and the relationships between these elements. Two summers of observation and comparison with the published work on the Great Crested Grebe give some insight into these ele• ments, their evolution, and their stimuli. Threat and escape behaviour have been seen in the courtship of many birds, and the threat-escape theory of courtship in general has been derived from these cases. In the two grebes described threat plays a much less important role than the theory prescribes, and may not even be important at all. In the two patterns where the evolutionary relation• ships are clear, the elements are those of comfort preening. -

Doctor of $Ijiio£Fopi)P in WILDLIFE SCIENCE

STUDY ON BIRD COMMUNITY STRUCTURE OF TERA1 FOREST IN DUDWA NATIONAL PARK SUMMARY > w ^i< '..J Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of $IjiIo£fopI)p IN WILDLIFE SCIENCE BY SALIM JAVED T'5o85 CENTRE OF WILDLIFE & ORNITHOLOGY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1996 SUMMARY Introduction Avian communities by virtue of being ecologically diverse are one of the most suitable biological materials for monitoring the health and functioning of an ecosystem. The diversity and richness of avian species in a community also mirrors the diversity and richness of the habitat. A large number of studies have explored this relationship. Study on the Bird Community Structure of terai forest in Dudwa National Park was started in 1991 as there have been no studies in the terai region. This region has witnessed some of the most drastic changes owing to the changed land use pattern and is also ornithologically poorly known. This study has been conceived to address certain questions regarding the avian community structure and to test whether the much discussed relationship between Bird Species Diversity (BSD) and Foliage Height Diversity (FHD) is applicable or not? The study also attempts to explore features of habitat that determine the avian community structure. The study also focussed on studying avian guilds using an objective approach. The objectives of the study were to 1. Conduct bird community studies in moist deciduous "terai" forest of Dudwa National Park. 2. Evaluarte bird species diversity (BSD), bird species richness (BSR), relative density and composition over a period of time. 3. Determine how various habitat parameters affect the species diversity and density. -

Evidence for Aviculture: Identifying Research Needs to Advance the Role of Ex Situ Bird Populations in Conservation Initiatives and Collection Planning

Review Evidence for Aviculture: Identifying Research Needs to Advance the Role of Ex Situ Bird Populations in Conservation Initiatives and Collection Planning Paul Rose 1,2 1 Centre for Research in Animal Behaviour, Psychology, University of Exeter, Perry Road, Exeter, Devon EX4 4QG, UK; [email protected] or [email protected] 2 WWT, Slimbridge Wetland Centre, Slimbridge, Gloucestershire GL2 7BT, UK Simple Summary: Birds of a whole range of species are housed in zoological collections globally; they are some of the most frequently seen of species in animal populations kept under human care. Research output on birds can provide valuable information on how to advance husbandry and care for particular species, which may further feed into conservation planning. Linking birds housed in human care to those in the wild adds value to these zoo-housed populations; this paper provides areas of research that could be conducted to add value to these zoo-housed birds and suggests increasing the conservation focus and conservation relevance of birds housed by humans. Abstract: Birds are the most speciose of all taxonomic groups currently housed in zoos, but this species diversity is not always matched by their inclusion in research output in the peer-reviewed literature. This large and diverse captive population is an excellent tool for research investigation, the findings of which can be relevant to conservation and population sustainability aims. The One Plan Approach to conservation aims to foster tangible conservation relevance of ex situ populations to those animals living in situ. The use of birds in zoo aviculture as proxies for wild-dwelling Citation: Rose, P. -

Aviculture Assisting Conservation

Whooping Crane Crus americana, Aviculture Peregrine Falcon Falco peregrinus anatum, and the California Condor Assisting Conservation Cymnogyps californianus. by Joanne Abramson, A Recent Example ofAviculture Fort Bragg, California Assisting Conservation What is Aviculture? weight gains, feeding of young, wean An example of one such opportuni he term "aviculturist" has com ing age can all be collected in aviary ty for this author to assist in conserva monly been applied to people settings. Eventually D A, hormone tion research occurred in 1993. The T in the private sector. In actuali and aging studies may be carried out. author became aware of a radio trans ty, it applies to anyone that is raising Captive bird photography often reveals mitter that was to be used on Buffon's birds and would include zoological what a researcher suspected, but could Macaws (Ara ambigua) in the wild by bird curators as well as government not observe in the wild. researchers Robin Bjork and George bird breeding facility managers. This Each species' biology is extremely VN. Powell working for RARE Center article takes a brief look at how avicul complex. Success of future release for Tropical Conservation. Buffon's ture can fit into the conservation pic programs is dependent on many other Macaws are uncommon birds in cap ture. species (including man, the greatest tivity and in the wild which are, unfor predator of all) which interplay with tunately, frequently misidentified as Who are Aviculturists? the subject species. For many of the the more common Military Macaw Aviculturists are a diverse group of species in the greatest danger of (Ara militaris).