After Watteau: Nicolas Lancret and the Creation of the Hunt Luncheon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shearer West Phd Thesis Vol 1

THE THEATRICAL PORTRAIT IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY LONDON (VOL. I) Shearer West A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St. Andrews 1986 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/2982 This item is protected by original copyright THE THEATRICAL PORTRAIT IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY LONDON Ph.D. Thesis St. Andrews University Shearer West VOLUME 1 TEXT In submitting this thesis to the University of St. Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the I work may be made and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker. ABSTRACT A theatrical portrait is an image of an actor or actors in character. This genre was widespread in eighteenth century London and was practised by a large number of painters and engravers of all levels of ability. The sources of the genre lay in a number of diverse styles of art, including the court portraits of Lely and Kneller and the fetes galantes of Watteau and Mercier. Three types of media for theatrical portraits were particularly prevalent in London, between ca745 and 1800 : painting, print and book illustration. -

Jeff King Recounts the Spread of Cycling’S Drug Culture from Europe to North America

THE JOURNAL Rider on the Storm Former pro cyclist Jeff King recounts the spread of cycling’s drug culture from Europe to North America. By Jeff King June 2013 All pihotos: Coutesy of Jeff Coutesy King All pihotos: Jeff King winning a pair of races in New York’s Central Park in 2006. The first thing I noticed in Belgium was the speed. We were racing at a pace at least five miles per hour faster than anything I had ever done in North America and not taking the usual rests that would allow me to survive three-hour races like this. I was getting my legs ripped off. 1 of 10 Copyright © 2013 CrossFit, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Subscription info at http://journal.crossfit.com CrossFit is a registered trademark ® of CrossFit, Inc. Feedback to [email protected] Visit CrossFit.com Rider ... (continued) I had arrived in Brussels the day before, fresh off a It was my first race and I was already thinking, “Man, these season of national-level professional races around the guys are fit.” U.S. The weekend before, I was still the team captain for the University of Colorado cycling team that won the collegiate national championships. I was named to the all-American team. I was in top form, winning races and confident I would win more, which is why I decided to In the late 1990s, there was a move to Belgium and compete as a professional cyclist. drug renaissance going on in The day before I arrived, I was on top of the world; the day European biking. -

HIP HOP & Philosophy

Devil and Philosophy 2nd pages_HIP HOP & philosophy 4/8/14 10:43 AM Page 195 21 Souls for Sale JEFF EWING F Y O Selling your soul to the Devil in exchaPnge for a longer life, wealth, beauty, power, or skill has long been a theme in Obooks, movies, and even music. Souls have Obeen sold for Rknowledge and pleasure (Faust), eternal youth (Dorian Gray), the ability to play the guitar (Tommy JohnCson in O Brother, Where Art P Thou?) or the harmonica (Willie “Blind Do g Fulton Smoke House” Brown in the 1986 Emovie, Crossroads), or for rock’n’roll itself (the way Black SCabbath did on thDeir 1975 greatest hits album, We Sold Our Soul for Rock’n’ERoll). The selling of aN soul as an object of exchange for nearly any- thing, as a sort of fictitious comTmodity with nearly universal exchange valuAe, makes it perChaps the most unique of all possi- ble commVodities (and as such, contracts for the sales of souls are the most unique of aEll possible contracts). One theorist in partiDcular, Karl MaRrx (1818–1883), elaborately analyzed con- tracts, exchange, and “the commodity” itself, along with all the hAidden implicatRions of commodities and the exchange process. Let’s see what Marx has to tell us about the “political economy” of the FaustOian bargain with the Devil, and try to uncover what it trulyC is to sell your soul. N Malice and Malleus Maleficarum UWhile the term devil is sometimes used to refer to minor, lesser demons, in Western religions the term refers to Satan, the fallen angel who led a rebellion against God and was banished from Heaven. -

Parcours Pédagogique Collège Le Cubisme

PARCOURS PÉDAGOGIQUE COLLÈGE 2018LE CUBISME, REPENSER LE MONDE LE CUBISME, REPENSER LE MONDE COLLÈGE Vous trouverez dans ce dossier une suggestion de parcours au sein de l’exposition « Cubisme, repenser le monde » adapté aux collégiens, en Un autre rapport au préparation ou à la suite d’une visite, ou encore pour une utilisation à distance. réel : Ce parcours est à adapter à vos élèves et ne présente pas une liste d’œuvres le traitement des exhaustive. volumes dans l’espace Ce dossier vous propose une partie documentaire présentant l’exposition, suivie d’une sélection d’œuvres associée à des questionnements et à des compléments d’informations. L’objectif est d’engager une réflexion et des échanges avec les élèves devant les œuvres, autour de l’axe suivant « Un autre rapport au réel : le traitement des volumes dans l’espace ». Ce parcours est enrichi de pistes pédadogiques, à exploiter en classe pour poursuivre votre visite. Enfin, les podcasts conçus pour cette exposition vous permettent de préparer et d’approfondir in situ ou en classe. Suivez la révolution cubiste de 1907 à 1917 en écoutant les chroniques et poèmes de Guillaume Apollinaire. Son engagement auprès des artistes cubistes n’a jamais faibli jusqu’à sa mort en 1918 et a nourri sa propre poésie. Podcasts disponibles sur l’application gratuite du Centre Pompidou. Pour la télécharger cliquez ici, ou flashez le QR code situé à gauche. 1. PRÉSENTATION DE L’EXPOSITION L’exposition offre un panorama du cubisme à Paris, sa ville de naissance, entre 1907 et 1917. Au commencement deux jeunes artistes, Georges Braque et Pablo Picasso, nourris d’influences diverses – Gauguin, Cézanne, les arts primitifs… –, font table rase des canons de la représentation traditionnelle. -

Programmation De France Médias Monde Format

Mardi 14 mars 2017 RFI ET FRANCE 24 MOBILISEES A L’OCCASION DE LA JOURNEE DE LA LANGUE FRANCAISE DANS LES MEDIAS Lundi 20 mars 2017 Le 20 mars, RFI et France 24 s’associent à la troisième édition de la « Journée de la langue française dans les médias », initiée par le CSA, dans le cadre de la « Semaine de la langue française et de la Francophonie ». A cette occasion, RFI délocalise son antenne à l’Académie française et propose une programmation spéciale avec notamment l’annonce dans l’émission « La danse des mots » des résultats de son jeu « Speakons français » qui invitait, cette année, les auditeurs et internautes à trouver des équivalents français à des anglicismes courants utilisés dans le monde du sport. France 24 consacre reportages et entretiens à l’enjeu de la qualité de la langue française employée dans les médias qui, plus qu’un simple outil de communication, est une manière de comprendre le monde en le nommant. Les rédactions en langues étrangères de RFI sont également mobilisées, notamment à travers leurs émissions bilingues, qui invitent les auditeurs à se familiariser à la langue française. Celles-ci viennent appuyer le travail du service RFI Langue française, qui à travers le site RFI SAVOIRS met à disposition du grand public et des professionnels de l’éducation des ressources et outils pour apprendre le français et comprendre le monde en français. Enfin, France 24 diffusera, du 20 au 26 mars, les spots de sensibilisation « Dites-le en français » , réalisés par les équipes de France Médias Monde avec France Télévisions et TV5MONDE. -

The Italian Comedians Probably 1720 Oil on Canvas Overall: 63.8 × 76.2 Cm (25 1/8 × 30 In.) Framed: 94.62 × 107 × 13.65 Cm (37 1/4 × 42 1/8 × 5 3/8 In.) Samuel H

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS French Paintings of the Fifteenth through Eighteenth Centuries Antoine Watteau French, 1684 - 1721 The Italian Comedians probably 1720 oil on canvas overall: 63.8 × 76.2 cm (25 1/8 × 30 in.) framed: 94.62 × 107 × 13.65 cm (37 1/4 × 42 1/8 × 5 3/8 in.) Samuel H. Kress Collection 1946.7.9 ENTRY Numerous paintings with figures in theatrical costume attest to Jean Antoine Watteau’s interest in the theater. In The Italian Comedians, however—as in others of his works in this genre—the identity of some of the characters remains uncertain or equivocal because he sometimes reused the same model for different figures and modified standard costumes according to his whim. Pierre Rosenberg has drawn attention to the announcement in the Mercure de France of the 1733 print after The Italian Comedians [fig. 1] by Bernard Baron (1696–1762): “These are almost all portraits of men skilled in their art, whom Watteau painted in the different clothing of the actors of the Italian Theatre.” [1] It would seem, then, that the painting does not record an actual performance; and we lack evidence as to who these individuals might actually be. It was Baron’s print (included in the Recueil Jullienne, the compendium of prints after Watteau’s work) that gave The Italian Comedians its title. The scene appears to represent a curtain call of the Comédie Italienne, the French version of the commedia dell’arte, which presented stock characters in predictably humorous plots. A red curtain has been drawn aside from a stage where fifteen figures stand together. -

André Derain Stoppenbach & Delestre

ANDR É DERAIN ANDRÉ DERAIN STOPPENBACH & DELESTRE 17 Ryder Street St James’s London SW1Y 6PY www.artfrancais.com t. 020 7930 9304 email. [email protected] ANDRÉ DERAIN 1880 – 1954 FROM FAUVISM TO CLASSICISM January 24 – February 21, 2020 WHEN THE FAUVES... SOME MEMORIES BY ANDRÉ DERAIN At the end of July 1895, carrying a drawing prize and the first prize for natural science, I left Chaptal College with no regrets, leaving behind the reputation of a bad student, lazy and disorderly. Having been a brilliant pupil of the Fathers of the Holy Cross, I had never got used to lay education. The teachers, the caretakers, the students all left me with memories which remained more bitter than the worst moments of my military service. The son of Villiers de l’Isle-Adam was in my class. His mother, a very modest and retiring lady in black, waited for him at the end of the day. I had another friend in that sinister place, Linaret. We were the favourites of M. Milhaud, the drawing master, who considered each of us as good as the other. We used to mark our classmates’s drawings and stayed behind a few minutes in the drawing class to put away the casts and the easels. This brought us together in a stronger friendship than students normally enjoy at that sort of school. I left Chaptal and went into an establishment which, by hasty and rarely effective methods, prepared students for the great technical colleges. It was an odd class there, a lot of colonials and architects. -

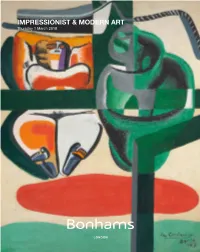

Impressionist & Modern

Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I 10 October 2019 Lot 8 Lot 2 Lot 26 (detail) Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I Thursday 10 October 2019, 5pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION IMPORTANT INFORMATION 101 New Bond Street London OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION The United States Government London W1S 1SR India Phillips PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO has banned the import of ivory bonhams.com Global Head of Department REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE into the USA. Lots containing +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF ivory are indicated by the VIEWING [email protected] ANY LOT. INTENDING BIDDERS symbol Ф printed beside the Friday 4 October 10am – 5pm MUST SATISFY THEMSELVES AS lot number in this catalogue. Saturday 5 October 11am - 4pm Hannah Foster TO THE CONDITION OF ANY LOT Sunday 6 October 11am - 4pm Head of Department AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 14 PRESS ENQUIRIES Monday 7 October 10am - 5pm +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 OF THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS [email protected] Tuesday 8 October 10am - 5pm [email protected] CONTAINED AT THE END OF THIS Wednesday 9 October 10am - 5pm CATALOGUE. CUSTOMER SERVICES Thursday 10 October 10am - 3pm Ruth Woodbridge Monday to Friday Specialist As a courtesy to intending bidders, 8.30am to 6pm SALE NUMBER +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 Bonhams will provide a written +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 25445 [email protected] Indication of the physical condition of +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 Fax lots in this sale if a request is received CATALOGUE Julia Ryff up to 24 hours before the auction Please see back of catalogue £22.00 Specialist starts. -

18Th Century. France and Venice

18th century. France and Venice Antoine Watteau (1684 – 1721) was a French painter whose brief career spurred the revival of interest in colour and movement, as seen in the tradition of Correggio and Rubens. He revitalised the waning Baroque style, shifting it to the less severe, more naturalistic, less formally classical, Rococo. Watteau is credited with inventing the genre of fêtes galantes, scenes of bucolic and idyllic charm, suffused with a theatrical air. Some of his best known subjects were drawn from the world of Italian comedy and ballet. The Love Song c1717 The Embarcation for Cythera 1717 The Embarkation for Cythera portrays a "fête galante"; an amorous celebration or party enjoyed by the aristocracy of France during the Régence after the death of Louis XIV, which is generally seen as a period of dissipation and pleasure, and peace, after the sombre last years of the previous reign. The work celebrates love, with many cupids flying around the couples and pushing them closer together, as well as the statue of Venus.There are three pairs of lovers in the foreground. While the couple on the right by the statue are still engaged in their passionate tryst, another couple rises to follow a third pair down the hill, although the woman of the third pair glances back fondly at the goddess’s sacred grove. At the foot of the hill, several more happy couples are preparing to board the golden boat at the left. With its light and wispy brushstrokes, the hazy landscape in the background does not give any clues about the season, or whether it is dawn or dusk. -

Impressionist & Modern

IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 at 5pm New Bond Street, London VIEWING ENQUIRIES Brussels Rome Thursday 22 February, 9am to 5pm London Christine de Schaetzen Emma Dalla Libera Friday 23 February, 9am to 5pm India Phillips +32 2736 5076 +39 06 485 900 Saturday 24 February, 11am to 4pm Head of Department [email protected] [email protected] Sunday 25 February, 11am to 4pm +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 Monday 26 February, 9am to 5pm [email protected] Cologne Tokyo Tuesday 27 February, 9am to 3pm Katharina Schmid Ryo Wakabayashi Wednesday 28 February 9am to 5pm Hannah Foster +49 221 2779 9650 +81 3 5532 8636 Thursday 1 March, 9am to 2pm Department Director [email protected] [email protected] +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 SALE NUMBER [email protected] Geneva Zurich 24743 Victoria Rey-de-Rudder Andrea Bodmer Ruth Woodbridge +41 22 300 3160 +41 (0) 44 281 95 35 CATALOGUE Specialist [email protected] [email protected] £22.00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 [email protected] Livie Gallone Moeller PHYSICAL CONDITION OF LOTS ILLUSTRATIONS +41 22 300 3160 IN THIS AUCTION Front cover: Lot 16 Aimée Honig [email protected] Inside front covers: Lots 20, Junior Cataloguer PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO 21, 15, 70, 68, 9 +44 (0) 20 7468 8276 Hong Kong REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE Back cover: Lot 33 [email protected] Dorothy Lin TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF +1 323 436 5430 ANY LOT. -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

1 BIBLIOGRAPHIE EXHAUSTIVE ET CHRONOLOGIQUE Stéphane

1 BIBLIOGRAPHIE EXHAUSTIVE ET CHRONOLOGIQUE Stéphane CASTELLUCCIO Chargé de recherche au CNRS, HDR Centre André Chastel UMR 8150 OUVRAGES 1. Le Château de Marly pendant le règne de Louis XVI, Prix Cailleux 1990, Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, collection scientifique Notes et documents des musées de France n° 29, 1996, 271 pages. 2. Le Style Louis XIII, Paris, Les Editions de l’Amateur, 2002, 142 pages. 3. Les Collections royales d’objets d’art de François Ier à la Révolution, préface d’Antoine Schnapper, professeur émérite à l’université de Paris IV-La Sorbonne, Paris, Les Editions de l’Amateur, 2002, 271 pages. Ouvrage récompensé par le Grand Prix de l’Académie de Versailles, Société des sciences morales, des lettres et des arts d’Ile de France en octobre 2003. 4. Les Carrousels en France du XVIe au XVIIIe siècle, Paris, L’Insulaire-Les Editions de l’Amateur, 2002, 172 pages. 5. Le Garde-Meuble de la Couronne et ses intendants, du XVIe au XVIIIe siècle, Paris, Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques, 2004, 333 pages. Epuisé. Réédité en 2007. 6. Les Fastes de la Galerie des Glaces. Recueil d’articles du Mercure galant. (1681-1773), présentation et annotations, Paris, Payot & Rivages, 2007. 7. Les Meubles de pierres dures de Louis XIV et l’atelier des Gobelins, Dijon, Editions Faton, 2007, 145 pages. 8. Le Goût pour les porcelaines de Chine et du Japon à Paris aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, Saint-Rémy-en- l’Eau, Editions Monelle Hayot, 2013, 224 pages. Publication en anglais en association avec le J.