The Popularity of Jazz–An Unpopular Problem: the Significance of ’Swing When You’Re Winning’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Im Auftrag: Medienagentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 01805 - 060347 90476 [email protected]

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 01805 - 060347 90476 [email protected] FRANK SINATRAS ZEITLOSE MUSIK WIRD WELTWEIT MIT DER KOMPLETTEN KARRIERE UMFASSENDEN JAHRHUNDERTCOLLECTION ‘ULTIMATE SINATRA’ GEFEIERT ‘Ultimate Sinatra’ erscheint als CD, Download, 2LP & limited 4CD/Digital Deluxe Editions und vereint zum ersten Mal die wichtigsten Aufnahmen aus seiner Zeit bei Columbia, Capitol und Reprise! “Ich liebe es, Musik zu machen. Es gibt kaum etwas, womit ich meine Zeit lieber verbringen würde.” – Frank Sinatra Dieses Jahr, am 12. Dezember, wäre Frank Sinatra 100 Jahre alt geworden. Anlässlich dieses Jubiläums hat Capitol/Universal Music eine neue, die komplette Karriere des legendären Entertainers umspannende Collection seiner zeitlosen Musik zusammengestellt. Ultimate Sinatra ist als 25 Track- CD, 26 Track-Download, 24 Track-180g Vinyl Doppel-LP und als limitierte 101 Track Deluxe 4CD- und Download-Version erhältlich und vereint erstmals die wichtigsten Columbia-, Capitol- und Reprise- Aufnahmen in einem Paket. Alle Formate enthalten bisher unveröffentlichte Aufnahmen von Sinatra und die 4CD-Deluxe, bzw. 2LP-Vinyl Versionen enthalten zusätzlich Download-Codes für weitere Bonustracks. Frank Sinatra ist die Stimme des 20. Jahrhunderts und seine Studiokarriere dauerte unglaubliche sechs Jahrzehnte: 1939 sang er seinen ersten Song ein und seine letzten Aufnahmen machte er im Jahr 1993 für sein weltweit gefeiertes, mehrfach mit Platin ausgezeichnetes Album Duets and Duets II. Alle Versionen von Ultimate Sinatra beginnen mit “All Or Nothing At All”, aufgenommen mit Harry James and his Orchestra am 31. August 1939 bei Sinatras erster Studiosession. Es war die erste von fast 100 Bigband-Aufnahmen mit den Harry James und Tommy Dorsey Orchestern. -

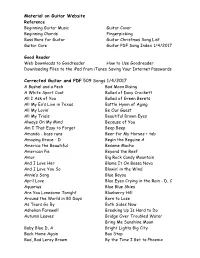

1Guitar PDF Songs Index

Material on Guitar Website Reference Beginning Guitar Music Guitar Cover Beginning Chords Fingerpicking Bass Runs for Guitar Guitar Christmas Song List Guitar Care Guitar PDF Song Index 1/4/2017 Good Reader Web Downloads to Goodreader How to Use Goodreader Downloading Files to the iPad from iTunes Saving Your Internet Passwords Corrected Guitar and PDF 509 Songs 1/4/2017 A Bushel and a Peck Bad Moon Rising A White Sport Coat Ballad of Davy Crockett All I Ask of You Ballad of Green Berets All My Ex’s Live in Texas Battle Hymn of Aging All My Lovin’ Be Our Guest All My Trials Beautiful Brown Eyes Always On My Mind Because of You Am I That Easy to Forget Beep Beep Amanda - bass runs Beer for My Horses + tab Amazing Grace - D Begin the Beguine A America the Beautiful Besame Mucho American Pie Beyond the Reef Amor Big Rock Candy Mountain And I Love Her Blame It On Bossa Nova And I Love You So Blowin’ in the Wind Annie’s Song Blue Bayou April Love Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain - D, C Aquarius Blue Blue Skies Are You Lonesome Tonight Blueberry Hill Around the World in 80 Days Born to Lose As Tears Go By Both Sides Now Ashokan Farewell Breaking Up Is Hard to Do Autumn Leaves Bridge Over Troubled Water Bring Me Sunshine Moon Baby Blue D, A Bright Lights Big City Back Home Again Bus Stop Bad, Bad Leroy Brown By the Time I Get to Phoenix Bye Bye Love Dream A Little Dream of Me Edelweiss Cab Driver Eight Days A Week Can’t Help Falling El Condor Pasa + tab Can’t Smile Without You Elvira D, C, A Careless Love Enjoy Yourself Charade Eres Tu Chinese Happy -

Damian O'neill

Damian O’Neill FREELANCE Editor : avid : fcp www.damianoneill.com [email protected] 15 years Granada TV (10 years as Senior Editor) 13 years freelance Recent work includes: Oman National Day 2010 Avantgarde Nobel Peace Prize Concert 2010, 09,08,07,06,05,04,03 Dinamo Story – NRK V Festival 2010, 09,08,07,06,05 Blink TV – C4 Celtic Thunder Christmas Celtic Thunder– PBS Arthur’s Day Concert 2009 Done n Dusted – ITV 10 Years of Westlife – Live at Croke Park Stadium Scarlet - Sony BMG Celtic Man in Celtic Thunder Celtic Man - PBS David Broza – Live at Massada WTTW - PBS Toto – Falling in Between Live Eagle Rock Lionel Richie – Live in Paris Scarlet-PBS Loreena McKennitt, Nights From The Alhambra Scarlet - PBS Destiny’s Child Live in Atlanta Scarlet - Sony BMG Christina Aguilera – Stripped in London Scarlet – WB Network R.E.M. The Perfect Square Scarlet – Warner Tina Turner-One Last Time Serpent Films - CBS Will Young Live in London Scarlet - Sony BMG Westlife Live In Stockholm-The Turnaround Tour Scarlet - BMG We Are The Future Concert 2004 MTV Italy Urban Music Festival 2004 Done n Dusted – C4 Sunday Night Classics MME - ZDF Blue Guilty Live From Wembley Scarlet - Virgin The Dome (16 x 3 hr concerts) MME – RTL Pepsi Silver Clef Concert Sanctuary Will Young Live 19 TV One Big Sunday BBC South Africa Freedom Concert Straight TV – C4 Simply Red Live in London Big Eye TV - Warner Crowded House – Farewell to the World MTV 1 This is JLS ITV An Audience with Michael Bublé ITV BBC Junior & Senior Choirs of the Year 2011, 10 BBC Songs of Praise -

Pioneers of the Concept Album

Fancy Meeting You Here: Pioneers of the Concept Album Todd Decker Abstract: The introduction of the long-playing record in 1948 was the most aesthetically signi½cant tech- nological change in the century of the recorded music disc. The new format challenged record producers and recording artists of the 1950s to group sets of songs into marketable wholes and led to a ½rst generation of concept albums that predate more celebrated examples by rock bands from the 1960s. Two strategies used to unify concept albums in the 1950s stand out. The ½rst brought together performers unlikely to col- laborate in the world of live music making. The second strategy featured well-known singers in song- writer- or performer-centered albums of songs from the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s recorded in contemporary musical styles. Recording artists discussed include Fred Astaire, Ella Fitzgerald, and Rosemary Clooney, among others. After setting the speed dial to 33 1/3, many Amer- icans christened their multiple-speed phonographs with the original cast album of Rodgers and Hammer - stein’s South Paci½c (1949) in the new long-playing record (lp) format. The South Paci½c cast album begins in dramatic fashion with the jagged leaps of the show tune “Bali Hai” arranged for the show’s large pit orchestra: suitable fanfare for the revolu- tion in popular music that followed the wide public adoption of the lp. Reportedly selling more than one million copies, the South Paci½c lp helped launch Columbia Records’ innovative new recorded music format, which, along with its longer playing TODD DECKER is an Associate time, also delivered better sound quality than the Professor of Musicology at Wash- 78s that had been the industry standard for the pre- ington University in St. -

CURRICULEM VITAE JARROD ROBERTS - Lighting Cameraman

[email protected] www.hillyerroberts.com tel +44 7816 847 487 Based: Manchester CURRICULEM VITAE JARROD ROBERTS - Lighting Cameraman With over 16 years experience as a professional lighting cameraman, I have worked in the UK, and worldwide on a diverse range of programmes - from documentaries, current affairs, entertainment, news and sport. I have worked for all the major UK broadcasters and have extensive hands on knowledge of all current broadcast formats and production techniques. Work Hillyer Roberts & Associates Ltd 2002 - Present Lighting Cameraman/ Founder Director Work portfolio BBC1 ITV includes: “Forgotten Heroes” Panorama “ “Do the Funniest things” Series “When Satan Came to Town” documentary “Tonight” “Countryfile” “Stars in Their Eyes” “Songs of Praise” “Celebrities Under Pressure” “The One Show” “Coronation Street Secrets” “Blackpool Medics” “My Favourite Hymns” “North West Tonight” Title sequences “ITV News” “The Money Programme” “Real Crime” “Watchdog” “Coronation Street” Break Bumpers “Sunday Life” “Breakfast” Channel 4 “Real Story” various “Food- What’s in your Basket” “Stealing Shakespeare” “Dispatches” “Location, Location, Location” BBC2 “How to Look Good Naked” “Generation Jihad” documentary “Goks Fashion Fix” “The Hairy Bakers” “Sex Education Show” “The Daily Politics” “Great British Menu” Ttle sequences Corporate 4:4:2 BBC3 Table Twelve media “Bingers” documentary Webs Edge “Destination Midnight” Title sequences HBL Media “Tiny Teens” First Angel Films “Anti Social Network” Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra -

Irish Pop Music in a Global Context by Oliver Patrick Cunningham

Irish Pop Music in a Global Context By Oliver Patrick Cunningham Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Regulations for the Attainment of the Degree of Masters of Arts in Sociology. National University of Ireland, Maynooth, Co. Kildare. Department of Sociology. July, 2000. Head of Department: Professor Liam Ryan. Research Supervisor: Dr. Colin Coulter. Acknowledgements There are gHite a number of people / wish to thank for helping me to complete this thesis. First and most important of all my family for their love and support notJust in my academic endeavors but also in all my different efforts so far, Thanks for your fate! Second / wish to thank all my friends both at home and in college in Maynooth for listening to me for the last ten months as I put this work together also for the great help and advice they gave to me during this period. Thanks for listeningl Third I wish to thank the staff in the Department of Sociology Nidi Maynooth, especially Dr, Colin Coulter my thesis supervisor for all their help and encouragement during the last year. Thanks for the knowledge/ Fourth / wish to thank the M A sociology class of 1999-2000 for being such a great class to learn, work and be friends with. Thanks for a great year! Fifth but most certainly not last / want to thank one friend who unfortunately was with us at the beginning of this thesis and gave me great encouragement to pursue it but could not stay to see the end result, This work is dedicated to your eternal memory Aoife. -

My Way: a Musical Tribute to Frank Sinatra Has Audiences, Artists Singing “The Best Is Yet to Come”

Sinatra Tribute Lights Up The Phoenix Theatre Company’s Outdoor Stage My Way: A Musical Tribute to Frank Sinatra has audiences, artists singing “The Best Is Yet To Come” (PHOENIX – March 18, 2021) The Phoenix Theatre Company concludes its series of socially- distanced outdoor shows with a swoon-worthy tribute to musical great Frank Sinatra. My Way: A Musical Tribute to Frank Sinatra features the story and music of the first great popstar. The high-energy production runs at The Phoenix Theatre Company’s socially-distanced outdoor venue April 14 through May 23. My Way: A Musical Tribute to Frank Sinatra is a walk down memory lane through the music of one of the greatest artists of all time. The production is set in a mid-century cabaret-style bar with an ensemble of four performers singing and dancing their way through vignettes of Sinatra’s life story. The Phoenix Theatre Company’s production includes modern touches in the costuming, an LED screen which serves as a backdrop and the high quality lighting and sound design audiences expect from The Phoenix Theatre Company. “Frank Sinatra was one of those rare performers who left audiences electrified,” says D. Scott Withers, director of My Way at The Phoenix Theatre Company. “His songs are timeless, tender and tough all at the same time. He drew people in with his approach to the lyrics and after the song ended, he left the air charged. He had a voltage.” The show includes Sinatra favorites and hidden gems performed by a three-piece orchestra and local Phoenix artists familiar to The Phoenix Theatre Company stage. -

Sinatra & Basie & Amos & Andy

e-misférica 5.2: Race and its Others (December 2008) www.hemisferica.org “You Make Me Feel So Young”: Sinatra & Basie & Amos & Andy by Eric Lott | University of Virginia In 1965, Frank Sinatra turned 50. In a Las Vegas engagement early the next year at the Sands Hotel, he made much of this fact, turning the entire performance—captured in the classic recording Sinatra at the Sands (1966)—into a meditation on aging, artistry, and maturity, punctuated by such key songs as “You Make Me Feel So Young,” “The September of My Years,” and “It Was a Very Good Year” (Sinatra 1966). Not only have few commentators noticed this, they also haven’t noticed that Sinatra’s way of negotiating the reality of age depended on a series of masks—blackface mostly, but also street Italianness and other guises. Though the Count Basie band backed him on these dates, Sinatra deployed Amos ‘n’ Andy shtick (lots of it) to vivify his persona; mocking Sammy Davis Jr. even as he adopted the speech patterns and vocal mannerisms of blacking up, he maneuvered around the threat of decrepitude and remasculinized himself in recognizably Rat-Pack ways. Sinatra’s Italian accents depended on an imagined blackness both mocked and ghosted in the exemplary performances of Sinatra at the Sands. Sinatra sings superbly all across the record, rooting his performance in an aura of affection and intimacy from his very first words (“How did all these people get in my room?”). “Good evening, ladies and gentlemen, welcome to Jilly’s West,” he says, playing with a persona (habitué of the famous 52nd Street New York bar Jilly’s Saloon) that by 1965 had nearly run its course. -

Title Artist Key Capo 20 C 500 Miles Proclaimers E a Groovy Kind Of

Title Artist Key Capo 20 C 500 Miles Proclaimers E A Groovy Kind Of Love Phil Collins C A House Is Not A Home Burt Bacharach Cm A night like this C Aber bitte mit Sahne Udo Jürgens F Abracadabra Steve Miller Am Achy Breaky Heart A Against All Odds Phil Collins Db Agua De Beber Dm Ai se eu te pego (Nossa Nossa) Michel Teló B Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers Am Aint nobody Em All about that bass Meghan Trainor A all blues Miles Davis C All summer long Kid Rock G All that she wants st: Ace Of Base C#m All The Things You Are Bbm Amazing Grace Misc. Traditional C Angels Robbie Williams E Another One Bites The Dust Queen F#m At Last F Atemlos B Auf Uns D Autumn Leaves Nat King Cole Gm Baby I love you Artist Name C Back To Black Amy Winehouse Dm Bad Moon Rising Creedence Clearwater Revival G Baker Street Gerry Rafferty Ab Bamboleo Gipsy Kings F#m Beautiful Christina Aguilera Eb Believe F# Bergwerk D Besame Mucho Joao Gilberto Am Best (the) F Billy Jean Michael Jackson F#m Birds And The Bees Misc. Unsigned Bands D Black Horse And Cherry Tree Kt Tunstall Em Black magic woman Santana Dm Blue Bossa} Cm Blue Moon Elvis Presley Cb Bobby Brown Frank Zappa C Book of love Artist Name A Brazil G Bubbly A Bye Bye Blackbird Db Calm after the storm Artist Name Ab Can't Help Falling In Love Elvis Presley D Can't wait until tonight_Max C Mutzke Candle In The Wind Elton John E Cocaine E Copacabana Barry Manilow Bbm Corazon espinado Bm Corcovado C Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Bm Country Roads 2 John Denver D Crazy Little Thing Called Love Queen D Daddy Cool Boney -

A Note on the Music: May Be Helpful to Play Said Frank Sinatra Songs While Reading / Indicates an Interruption

A note on the music: May be helpful to play said Frank Sinatra songs while reading / indicates an interruption Characters: EZRA – 17. JEANNE– 21. MURPHY – 35. Setting: Pharmacy storefront. Upstage door to a mall. [Over the mall speakers play a series of Frank Sinatra songs quietly overhead. “It was a very good year” It repeats with or without lyrics until next specified change. All is calm. Bright lights. Regular business. Explosion. Panic. Running. Gun shots. Shelves pushed over. Ransacking. Small fires ignite. All lights out but one LED bulb. EZRA hobbles in, holding his bloodied leg. Kicking things with it. Painful. Looking for something, he looks at the aisle signs. Sees what he needs. He digs. Reveals a bottle of hand sanitizer. Loud sounds from outside and footsteps. Bulky men run by. EZRA is still. He looks back at the aisle signs. Sees what he needs. He digs. Reveals a sewing kit. He sits and props himself against one of the few standing shelves, rips the packaging for the sewing needles, opens the sanitizer, proceeds to tend to his wound.] EZRA: Yesterday began in a hue of grey, as all grey days do. Bits of rain and snow, but mostly just grey. Went about the daily routine. I got up. Ate my Chocolate Special K. Had coffee. Spat it out cuz I hate everything about coffee. I am trying to build up my tolerance. Brushed. Said bye to the dog. Went to school. Normal day. Slept in Ms. Grover’s. Flirted in Madame Rubin’s. Paid attention in Mr. Jatrun’s, cuz I actually learn things there. -

Sandbox MUSIC MARKETING for the DIGITAL ERA Issue 98 | 4Th December 2013

Sandbox MUSIC MARKETING FOR THE DIGITAL ERA Issue 98 | 4th December 2013 Nordic lights: digital marketing in the streaming age INSIDE… Campaign Focus Sweden and Norway are bucking PAGE 5 : the trend by dramatically Interactive video special >> growing their recorded music Campaigns incomes and by doing so PAGE 6 : through streaming. In countries The latest projects from the where downloading is now a digital marketing arena >> digital niche, this has enormous implications for how music Tools will be marketed. It is no longer PAGE 7: about focusing eff orts for a few RebelMouse >> weeks either side of a release but Behind the Campaign rather playing the long game and PAGES 8 - 10: seeing promotion as something Primal Scream >> that must remain constant rather Charts than lurch in peaks and troughs. The Nordics are showing not just PAGE 11: where digital marketing has had Digital charts >> to change but also why other countries need to be paying very close attention. Issue 98 | 4th December 2013 | Page 2 continued… In 2013, alongside ABBA, black metal and OK; they still get gold- and platinum-certiied CEO of Sweden’s X5 Music latpack furniture, Sweden is now also singles and albums based on streaming Group, explains. “The known internationally for music streaming. revenues [adjusted].” marketing is substantially It’s not just that Spotify is headquartered di erent as you get paid in Stockholm; streaming has also famously Streaming is changing entirely the when people listen, not when turned around the fortunes of the Swedish marketing narrative they buy. You get as much recorded music industry. -

Noël En Musique

Noël en musique Silent night [Sonore musical] / partie vocale Mahalia Jackson ; ens. instr.. - : Delta music, 1990. - 47:26 : ADD. PCDM4 : 1.2 Centre(s) d'intérêt : Gospel, Negro-spiritual (musique) 1.2 JAC Noël (musique) Gospel Christmas with Mahalia Jackson EAN 4006408153009 Christmas [Sonore musical] / partie vocale Michael Bublé ; piano Alan Pasqua ; contrebasse Chuck Berghofer ; batterie Peter Erskine ; ens. instr.. - : Reprise Records, 2011. - 52:13. PCDM4 : 1.33 1.3 BUB 3 Centre(s) d'intérêt : Noël (musique) Chanteuse, chanteur jazz (musique) EAN 0093624953425 Holly and Ivy [Sonore musical] / partie vocale Natalie Cole ; piano Terry Trotter ; guitare basse Jim Hughart ; batterie Harold Jones ; guitare John Chiodini ; ... et al.. - : Elektra, 1994. - 46:58. PCDM4 : 1.33 1.3 COL 3 Centre(s) d'intérêt : Noël (musique) Chanteuse, chanteur jazz (musique) EAN 0075596170420 Christmas with the Puppini Sisters [Sonore musical] / ensemble vocal The Puppini Sisters ; ens. instr.. - : The Verve, 2010. - 34:28. PCDM4 : 1.39 Centre(s) d'intérêt : Noël (musique) 1.3 PUP 9 EAN 602527503943 1.4 BOY 31 Christmas interpretations [Sonore musical] / ensemble vocal Boyz II Men ; ens. instr.. - : Motown, 1993. - 41:06. PCDM4 : 1.431 Centre(s) d'intérêt : Noël (musique) R'n'B, New Jack (musique) EAN 073145302 The Spirit of Christmas [Sonore musical] / chant et claviers Ray Charles ; ens. instr. ; saxophone ténor Rudy Johnson ; trompette Freddie Hubbard ; guitare Jeff Pevar. - [S. L.] : Concord Music Group, 1985. - 47:30. PCDM4 : 1.413 1.4 CHA 13 Centre(s) d'intérêt : Noël (musique) EAN 0888072316713 All Star Christmas [Vidéos, films, diapositives] / partie vocale Mariah Carey ; Ensemble vocal et instrumental U2 ; partie vocale Elton John ; Ensemble vocal et instrumental Destiny's child ; partie vocale Christina Aguilera ; partie vocale Snoop Doggy Dogg ; Ensemble vocal et instrumental Wham ; partie vocale Gloria Estefan ; chant et guitare 2 A John "Cougar" Mellencamp.