Clinical Concepts on Thyroid Emergencies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thyroid Hormone Misuse and Abuse

Endocrine (2019) 66:79–86 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-019-02045-1 REVIEW Thyroid hormone misuse and abuse Victor J. Bernet 1,2 Received: 11 June 2019 / Accepted: 2 August 2019 © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Thyroid hormone (TH) plays an essential role in human physiology and maintenance of appropriate levels is important for good health. Unfortunately, there are instances in which TH is misused or abused. Such misuse may be intentional such as when individuals take thyroid hormone for unapproved indications like stimulation of weight loss or improved energy. There are instances where healthcare providers prescribe thyroid hormone for controversial or out of date uses and sometimes in supraphysiologic doses. Othertimes, unintentional exposure may occur through supplements or food that unknowingly contain TH. No matter the reason, exposure to exogenous forms of TH places the public at risk for potential adverse side effects. Keywords Thyrotoxicosis ● Thyroid hormone abuse ● Thyroid hormone misuse ● Factitious thyrotoxicosis ● Supplements ● 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: Analogs Overdose Thyroid hormone misuse and abuse secondary to exogenous TH ingestion that may be unin- tentional or purposeful such as in some cases of Munch- Almost any substance that impacts body physiology and ausen syndrome. Instances of TH misuse can be associated function is at risk for misuse or frank abuse, usually in the with the development of significant side effects. There are misgiven belief that the particular agent whether it be a other instances of chronic, low-grade over treatment with herb, supplement, medication, or hormone has healing TH, which occur for various misreasoning such as weight properties beyond that of which it actually possesses. -

Thyroid Disease Update

10/11/2017 Thyroid Disease Update • Donald Eagerton M.D. Disclosures I have served as a clinical investigator and/or speakers bureau member for the following: Abbott, Astra Zenica, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and Sanofi Aventis Thyroid Disease Update • Hypothyroidism • Hyperthyroidism • Thyroid Nodules • Thyroid Cancer 1 10/11/2017 2 10/11/2017 Case 1 • 50 year old white female is seen for follow up. Notices cold intolerance, dry skin, and some fatigue. Cholesterol is higher than prior visits. • Family history; Mother had history of hypothyroidism. Sister has hypothyroidism. • TSH = 14 (0.30- 3.3) Free T4 = 1.0 (0.95- 1.45) • Weight 70 kg Case 1 • Next step should be • A. Check Free T3 • B. Check AntiMicrosomal Antibodies • C. Start Levothyroxine 112 mcg daily • D. Start Armour Thyroid 30 mg q day • E. Check Thyroid Ultrasound Case 1 Next step should be • A. Check Free T3 • B. Check AntiMicrosomal Antibodies • C. Start Levothyroxine 112 mcg daily • D. Start Armour Thyroid 30 mg q day • E. Check Thyroid Ultrasound 3 10/11/2017 Hypothyroidism • Incidence 0.1- 2.0 % of the population • Subclinical hypothyroidism in 4-10% of the adult population • 5-8 times higher in women An FT4 test can confirm hypothyroidism 13 • In the presence of high TSH and FT4 levels in relation to the thyroid function TSH, low FT4 (free thyroxine) usually signalsTSH primary hypothyroidism12 Overt Mild Mild Overt Euthyroidism FT4 Hypothyroidism Thyrotoxicosis* Thyrotoxicosis vs. hyperthyroidism¹ While these terms are often used interchangeably, thyrotoxicosis (toxic thyroid), describes presence of too much thyroid hormone, whether caused by thyroid overproduction (hyperthyroidism); by leakage of thyroid hormone into the bloodstream (thyroiditis); or by taking too much thyroid hormone medication. -

A Case of Thyrotoxic Paralysis Caused by Consumption of Iodocaseine

Journal of Health and Social Sciences 2019; 4,2:277-282 CASE REPORT IN EMERGENCY MEDICINE A case of thyrotoxic paralysis caused by consumption of iodocaseine Antonio Villa1, Gabriella Nucera2 Affiliations: 1 M.D., Department of Emergency, ASST Monza, PO Desio, Monza, Italy 2 M.D., Department of Emergency Medicine, ASST Fatebenefratelli-Sacco, PO Fatebenefratelli, Milano, Italy Corresponding author: Dr Antonio Villa, ASST Monza, PO Desio. Via Fiuggi, 56 20159 Milan, Italy. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Acute hypokalaemic paralysis is a rare but treatable cause of acute limb weakness. Thyrotoxic paralysis is an uncommon, potentially life-threatening endocrine emergency and it is a rare complication of hyperthyroidism. The most common causes of hyperthyroidism include Graves’ disease, multinodular goiters or solitary thyroid nodule, and iodine-induced thyrotoxicosis ( Jod-Basedow syndrome). Thyreotoxicosis factitia, which is caused by the excessive ingestion of exogenous thyroid hormone or iodine derivatives administration, has been rarely reported as a cause of thyrotoxic paralysis. We describe the case of a young Caucasian male with flaccid paralysis of all four limbs and severe hypokalaemia after inappropriate iodine derivatives (iodocasein) intake to show, in conclusion, how critical care physicians need to be aware of this rare but curable condition. KEY WORDS: Iodocaseine; hypokalaemia; thyrotoxic paralysis. 277 Journal of Health and Social Sciences 2019; 4,2:277-282 Riassunto La paralisi acuta ipokaliemica è una causa rara ma curabile di astenia acuta. La paralisi tireotossica è un'e- mergenza endocrina non comune e potenzialmente pericolosa per la vita ed è una rara complicanza dell'i- pertiroidismo. L'ipertiroidismo è causato prevalentemente dalla malattia di Graves, da gozzi singoli o multi- nodulari, e dalla malattia indotta da iodio ( Jod-Basedow). -

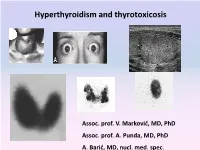

Hyperthyroidism and Thyrotoxicosis

Hyperthyroidism and thyrotoxicosis Assoc. prof. V. Marković, MD, PhD Assoc. prof. A. Punda, MD, PhD A. Barić, MD, nucl. med. spec. Hyperthyroidism- Thyrotoxicosis Hyperthyroidism- elevated serum levels of thyroid hormones caused by overproduction of thyroid hormones Thyrotoxicosis: elevated serum level of thyroid hormones/ excessive amount of circulating thyroid hormone Hyperthyreoidism includes thyreotoxycosis but Thyrotoxicosis is not exclusively caused by hyperthyroidism Classification of thyrotoxicosis Hyperthyroidism Thyrotoxicosis without hyperthyroidism Mb Basedow-Graves Thyrotoxicosis factitia Multinodular toxic goiter Subacute thyroiditis (painfull) Toxic adenoma Subacute thyroiditis (painless) Elevated TSH levels Ectopic thyroid tissue Trophoblastic tumors Iod-Basedow Diffuse toxic goiter (Mb Basedow, Graves) Diffuse toxic goiter Mb. Graves-Basedow Epidemiology and etiology Diffuse toxic goiter (Mb. Graves- Basedow) is an autoimune, multysistemic dissease, wich includes the thyoid gland, infiltrative ophthalmopathy, dermopathy and acropathy. World wide prevalence is about 0,4-2% in women, 0,1% in men, includes 60-90% of hyperthyroidism cases*. It is complex disease with predominant genetic component.& Sex hormones, stress. Disease is caused by TSH receptor stimulating antibodies/ TSH stimulating antibodies (TSAb), in 80-100% patients. *Taunbridge WMG, Vanderpump MPJ. Population screening for autoimmune thyroid disease. Endocriol Metab Clin North Am. 2000;29:239-253. &Brix TH, Kyvik KO, Christensen K, et al. Evdence for a major -

Thyroid Vascularity and Blood Flow

European Journal of Endocrinology (1999) 140 452–456 ISSN 0804-4643 Thyroid vascularity and blood flow are not dependent on serum thyroid hormone levels: studies in vivo by color flow doppler sonography Fausto Bogazzi, Luigi Bartalena, Sandra Brogioni, Alessandro Burelli, Luca Manetti, Maria Laura Tanda, Maurizio Gasperi and Enio Martino Dipartimento di Endocrinologia e Metabolismo, Ortopedia e Traumatologia, Medicina del Lavoro, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy (Correspondence should be addressed to E Martino, Dipartimento di Endocrinologia e Metabolismo, Ortopedia e Traumatologia, Medicina del Lavoro, Universita` di Pisa, Ospedale di Cisanello, Via Paradisa, 2, 56122 Pisa, Italy) Abstract Objective: Thyroid blood flow is greatly enhanced in untreated Graves’ disease, but it is not known whether it is due to thyroid hormone excess or to thyroid hyperstimulation by TSH-receptor antibody. To address this issue in vivo patients with different thyroid disorders were submitted to color flow doppler sonography (CFDS). Subjects and methods: We investigated 24 normal subjects, and 78 patients with untreated hyperthy- roidism (49 with Graves’ hyperthyroidism, 24 with toxic adenoma, and 5 patients with TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma (TSHoma)), 19 patients with thyrotoxicosis (7 with thyrotoxicosis factitia, and 12 with subacute thyroiditis), 37 euthyroid patients with goitrous Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, and 21 untreated hypothyroid patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Results: Normal subjects had CFDS pattern 0 (absent or minimal intraparenchimal spots) and mean intraparenchimal peak systolic velocity (PSV) of 4.8 6 1.2 cm/s. Patients with spontaneous hyperthy- roidism due to Graves’ disease, TSHoma, and toxic adenoma had significantly increased PSV (P < 0.0001, P = 0.0004, P < 0.0001 respectively vs controls) and CFDS pattern. -

Hypothyroidism: Mimicker of Common Complaints Matthew C

Emerg Med Clin N Am 23 (2005) 649–667 Hypothyroidism: Mimicker of Common Complaints Matthew C. Tews, DOa, Sid M. Shah, MD, FACEPb,*, Ved V. Gossain, MD, FACP, FACEPc aCollege of Osteopathic Medicine, Emergency Medicine Residency Program, Michigan State University–Lansing, P.O. Box 30480, Lansing, MI 48909, USA bMichigan State University, Attending Physician Emergency Medicine, Ingham Regional Medical, Center 401 W. Greenlawn Avenue, Lansing, MI 48910, USA cDivision of Endocrinology, Department of Medicine, Michigan State University, Lansing, MI 48909, USA Patients with hypothyroidism may present with vague symptoms such as fatigue, arthralgias, myalgias, muscle cramps, headaches, and ‘‘not feeling well.’’ These are also among the more common complaints encountered by the emergency physicians. The disease spectrum of hypothyroidism ranges from an asymptomatic, subclinical condition to the rare, life-threatening myxedema coma, and thus can be a challenging diagnosis to make. A progressive and chronic disease, hypothyroidism results from diminished thyroid hormone production. It slows metabolic functions in every organ system in the body. Commonly, clinical presentation of hypothyroidism can be confused with effects of aging in the elderly, musculoskeletal or a psychiatric illness such as depression in the younger patients. Spontaneously occurring hypothyroidism is relatively common, with prevalence between 1% to 2%, and is 10 times more common in women than in men [1]. The probability of developing spontaneous hypothyroidism increases with age, with women having a mean age at diagnosis of around 60 years [2]. A recent survey showed that 9.5% out of nearly 26,000 visitors to a statewide health fair in Colorado had elevated circulating thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) levels, indicating underlying hypothyroidism [3]. -

Endocrine Emergencies

Endocrine Emergencies • Neuroendocrine response to Critical illness • Thyroid storm/Myxedema Coma • Adrenal Crisis/Sepsis • Hyper/Hypocalcemia • Hypoglycemia • Hyper and Hyponatremia • Pheochromocytoma crises CASE 76 year old man presents with urosepsis and is Admitted to MICU. He has chronic renal insufficiency. During his hospital course, he is intubated and treated With dopamine. Thyroid studies are performed for Inability to wean from ventilator. What labs do you want? Assessment of Thyroid Function • Hormone Levels: Total T4, Total T3 • Binding proteins: TBG, (T3*) Resin uptake • Free Hormone Levels: TSH, F T4, F T3, Free Thyroid Index, F T4 by Eq Dialysis • Radioactive Iodine uptake (RAIU); primarily for DDx of hyperthyroidism • Thyroid antibodies; TPO, Anti-Thyroglobulin, Thyroid stimulating immunoglobulins, Th receptor antibodies Labs: T4 2.4 ug/dl (5-12) T3U 40% (25-35) FTI 1.0 (1.2-4.2) FT4 0.6 (0.8-1.8) TSH 0.2 uU/ml (.4-5.0) Non-thyroidal illness • Hypothesis: NTI vs 2° Hypothyroidism –RT3 ↑ in NTI and ↓ in Hypothyroidism • Hypothesis: NTI vs Hyperthyroidism – TT3 ↓ in NTI and in ↑ Hyperthyroidism • 75 year old woman with history of hypothyroidism is found unresponsive in her home during a cold spell in houston. No heat in the home. • Exam: T° 95, BP 100/60, P 50, RR 8 • Periorbital edema, neck scar, no rub or gallop, distant heart sounds, crackles at bases, peripheral edema • ECG: Decreased voltage, runs of Torsade de pointes • Labs? Imaging? • CXR: cardiomegaly • Glucose 50 • Na+ 120, K+ 4, Cl 80, HCO3¯ 30 • BUN 30 Creat 1.4 • ABG: pH 7.25, PCO2 75, PO2 80 • CK 600 • Thyroid studies pending • Management: Manifestations of Myxedema Coma • Precipitated by infection, iatrogenic (surgery, sedation, diuretics) • Low thyroid studies • Hypothermia • Altered mental status • Hyponatremia • ↑pCO2 • ↑CK • ↑Catecholamines with ↑vascular resistance • Cardiac: low voltage, Pericardial effusion, impaired relaxation with ↓C.O. -

Thyrotoxic Crisis

THYROTOXIC CRISIS INTRODUCTION (KATRINA KNAPP, D.O., 4/2016) Thyrotoxicosis is the clinical manifestation of hyperthyroidism. Thyrotoxic crisis, otherwise known as thyroid storm, is a life threatening condition that involves multi-organ system dysfunction including severe cardiovascular, thermoregulatory, gastrointestinal, and neurobehavioral symptoms. It is seen in less than 1% of adults with hyperthyroidism and is rarer in children. It has a high mortality rate (10-30%) if not recognized early and treated aggressively. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY Thyroid hormones are produced in the thyroid gland under the influence of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH). Thyroid releasing hormone (TRH) from the hypothalamus stimulates TSH release from the pituitary. In order to maintain thyroid hormone levels in normal range, circulating levels of thyroid hormones exert feedback inhibition on the hypothalamus and pituitary axis (HPA). There are 2 active thyroid hormones: triiodothyronine (T3) and L-thyroxine (T4). T4 is exclusively made in the thyroid gland. T3 is also made in the thyroid but 80% is made in the peripheral tissues by de-iodination of T4. Iodine is essential for thyroid hormone synthesis. T4 is more abundant than T3 and a greater proportion is protein bound (e.g. TBG, thyroid binding globulin). Only 0.03% of T4 is unbound. It is the unbound (“free”) hormones that are active. A greater proportion of T3 is the free form, and has a greater affinity (10 fold) for tissue thyroid hormone receptors than T4. T4 can also be metabolized to reverse T3 which is completely inactive. Most of the biologic activity of thyroid hormones is due to T3, but it is less reliably identified which is why we typically measure free T4. -

Recurrent Concurrent Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Thyroid Storm

Open Access Case Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.14273 Recurrent Concurrent Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Thyroid Storm David F. Crudo 1 , Elizabeth T. Walsh 1 , Janel D. Hunter 1 1. Pediatric Endocrinology, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, USA Corresponding author: David F. Crudo, [email protected] Abstract Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and thyroid storm are serious complications of underlying disease states. Either condition can induce the other, and the co-occurrence of these conditions is uncommon. We present the case of an adolescent patient with type 1 diabetes and autoimmune hypothyroidism who developed recurrent concurrent DKA and thyroid storm twice in an eight-month period. The simultaneous development of DKA and thyroid storm is uncommon with only 28 cases previously reported. Co- presentation of these two life-threatening conditions occurs in people with either preexisting diabetes, thyroid disease, or both. The purported pathophysiology of how DKA and thyroid storm affect the other is discussed. Categories: Endocrinology/Diabetes/Metabolism Keywords: diabetic ketoacidosis, thyroid storm, thyrotoxicosis, autoimmune thyroid disease Introduction Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a serious life-threatening complication of diabetes mellitus in which severe insulin deficiency leads to hyperglycemia, metabolic acidosis, dehydration, and electrolyte imbalances. The initial onset of diabetes, omissions in insulin therapy, and infections are common triggering factors [1]. Thyroid storm is an acute complication of hyperthyroidism typically precipitated by uncontrolled hyperthyroidism, discontinuation of antithyroid drugs, surgery, infection, trauma, or metabolic derangements [2]. DKA can be induced by thyroid storm and vice versa [3]. Although the co-occurrence of these entities is uncommon, each is potentially life-threatening without prompt recognition and appropriate therapy. -

Endocrine Module (PYPP 5260), Thyroid Section, Spring 2002

Endocrine Module (PYPP 5260), Thyroid Section, Spring 2002 THYROID HORMONE TUTORIAL: THYROID PATHOLOGY Jack DeRuiter I. INTRODUCTION Thyroid disorder is a general term representing several different diseases involving thyroid hormones and the thyroid gland. Thyroid disorders are commonly separated into two major categories, hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, depending on whether serum thyroid hormone levels (T4 and T3) are increased or decreased, respectively. Thyroid disease generally may be sub-classified based on etiologic factors, physiologic abnormalities, etc., as described in each section below. More than 13 million Americans are affected by thyroid disease, and more than half of these remain undiagnosed. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) has initiated a campaign to increase public awareness of thyroid disorders and educate Americans about key periods, from birth to advanced age, when people are at increased risk for developing a thyroid disorder (see below). The diagnosis of thyroid disease can be particularly challenging. Patients often present with vague, general clinical manifestations; in particular, the elderly may not associate the signs and symptoms with a disease process and thus may not bring them to the attention of their primary care provider. The prevalence and incidence of thyroid disorders is influenced primarily by sex and age. Thyroid disorders are more common in women than men, and in older adults compared with younger age groups. The prevalence of unsuspected overt hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism are both estimated to be 0.6% or less in women, based on several epidemiologic studies. Age is also a factor; for overt hyperthyroidism, the prevalence rate is 1.4% for women aged 60 or older and 0.45% for women aged 40 to 60. -

Thyroid Emergencies

REVIEW ARTICLE Thyroid emergencies Dorina Ylli1, Joanna Klubo ‑Gwiezdzinska2, Leonard Wartofsky3,4 1 Endocrinology Division, University of Medicine, Tirana, Albania 2 National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, United States 3 Endocrinology Division, Department of Medicine, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington DC, United States 4 MedStar Health Research Institute, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington DC, United states KEY WORDS ABSTRACT coma, critical care, Myxedema coma and thyroid storm are among the most common endocrine emergencies presenting to hypothermia, general hospitals. Myxedema coma represents the most extreme, life ‑threatening expression of severe hypothyroidism, hypothyroidism, with patients showing deteriorating mental status, hypothermia, and multiple organ thyrotoxicosis system abnormalities. It typically appears in patients with preexisting hypothyroidism via a common pathway of respiratory decompensation with carbon dioxide narcosis leading to coma. Without early and appropriate therapy, the outcome is often fatal. The diagnosis is based on history and physical find‑ ings at presentation and not on any objective thyroid laboratory test. Clinically based scoring systems have been proposed to aid in the diagnosis. While it is a relatively rare syndrome, the typical patient is an elderly woman (thyroid hypofunction being much more common in women) who may or may not have a history of previously diagnosed or treated thyroid dysfunction. Thyrotoxic storm or thyroid crisis is also a rare condition, established on the basis of a clinical diagnosis. The diagnosis is based on the pres‑ ence of severe hyperthyroidism accompanied by elements of systemic decompensation. Considering that mortality is high without aggressive treatment, therapy must be initiated as early as possible in a critical care setting. -

Thyroid Emergencies

The Art and Science of Infusion Nursing Angela M. Leung , MD, MSc Thyroid Emergencies cal manifestations, diagnostic methods, and treatments of ABSTRACT hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism, both in the Myxedema coma and thyroid storm are thyroid nonacute and life-threatening forms of these diseases. emergencies associated with increased mortality. Prompt recognition of these states—which repre- sent the severe, life-threatening conditions of THYROID HORMONE PRODUCTION AND METABOLISM extremely reduced or elevated circulating thyroid hormone concentrations, respectively—is neces- sary to initiate treatment. Management of myxe- The normal physiology of the hypothalamic-pituitary- dema coma and thyroid storm requires both med- thyroid axis involves the production of T4 and T3 by the thyroid gland, a process that is regulated by thyroid- ical and supportive therapies and should be treated stimulating hormone (TSH) secreted by the pituitary, in an intensive care unit setting. which is, in turn, regulated by thyrotropin-releasing hor- Key words: hypothyroidism , hyperthyroidism , mone (TRH) secreted by the hypothalamus. Both serum ICU , myxedema coma , thyroid emergencies , T4 and T3 concentrations act as negative feedback regu- thyroid storm lators of TSH and TRH secretion, but can be altered by environmental conditions—including food availability he thyroid is a 15- to 20-gram gland located and temperature—and disease states, such as infection. 1 in the anterior neck. It is responsible for the Thyroid hormone synthesis is achieved first through production of the thyroid hormones T4 (thy- active transport of circulating iodide, which is taken in roxine) and T3 (triiodothyronine). Various from the diet, by the sodium/iodide symporter located at factors can affect thyroid hormone synthesis, the basolateral membrane of the thyroid follicular cell.