Chapter 1. the Context of Polish Immigration and Integration in Iceland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Norðurland Vestra

NORÐURLAND VESTRA Stöðugreining 2019 20.03.2020 Ritstjórn: Laufey Kristín Skúladóttir. Aðrir höfundar efnis: Sigurður Árnason, Jóhannes Finnur Halldórsson, Einar Örn Hreinsson, Anna Lea Gestsdóttir, Guðmundur Guðmundsson, Sigríður Þorgrímsdóttir, Anna Lilja Pétursdóttir og Snorri Björn Sigurðsson. ISBN: 978-9935-9503-5-2 2 Norðurland vestra 5.4 Opinber störf .......................................................................................... 28 Stöðugreining 2019 6. Önnur þjónusta ............................................................................................ 31 6.1 Verslun .................................................................................................. 31 6.2 Ýmis þjónusta ........................................................................................ 31 Efnisyfirlit Inngangur .......................................................................................................... 6 6.3 Ferðaþjónusta ....................................................................................... 32 1. Norðurland vestra, staðhættir og sérkenni ................................................... 7 7. Landbúnaður ............................................................................................... 35 1.1 Um svæðið .............................................................................................. 7 7.1 Kjötframleiðsla ....................................................................................... 35 1.2 Íbúaþéttleiki ............................................................................................ -

UNWTO/DG GROW Workshop Measuring the Economic Impact Of

UNWTO/DG GROW Workshop Measuring the economic impact of tourism in Europe: the Tourism Satellite Account (TSA) Breydel building – Brey Auditorium Avenue d'Auderghem 45, B-1040 Brussels, Belgium 29-30 November 2017 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Title First name Last name Institution Position Country EU 28 + COSME COUNTRIES State Tourism Committee of the First Vice Chairman of the State Tourism Mr Mekhak Apresyan Armenia Republic of Armenia Committee of the Republic of Armenia Trade Representative of the RA to the Mr Varos Simonyan Trade Representative of the RA to the EU Armenia EU Head of balance of payments and Ms Kristine Poghosyan National Statistical Service of RA Armenia foreign trade statistics division Mr Gagik Aghajanyan Central Bank of the Republic of Armenia Head of Statistics Department Armenia Mr Holger Sicking Austrian National Tourist Office Head of Market Research Austria Federal Ministry of Science, Research Ms Angelika Liedler Head of International Tourism Affairs Austria and Economy Department of Tourism, Ministry of Consultant of Planning and Organization Ms Liya Stoma Sports and Tourism of the Republic of Belarus of Tourism Activities Division Belarus Ms Irina Chigireva National Statistical Committee Head of Service and Domestic Trade Belarus Attachée - Observatoire du Tourisme Ms COSSE Véronique Commissariat général au Tourisme Belgium wallon Mr François VERDIN Commissariat général au Tourisme Veille touristique et études de marché Belgium 1 Title First name Last name Institution Position Country Agency for statistics of Bosnia -

ICELAND Europe | Reykjavik, Akureyri, Húsavík, Lake Mývatn

ICELAND Europe | Reykjavik, Akureyri, Húsavík, Lake Mývatn Iceland EUROPE | Reykjavik, Akureyri, Húsavík, Lake Mývatn Season: 2021 Standard 8 DAYS 17 MEALS 28 SITES Revel in the unparalleled natural beauty of Iceland as you explore its dramatic landscapes that feature majestic waterfalls, lunar-like valleys, mountainous glaciers and stunning volcanoes. You’ll also savor culinary flavors and take part in the local traditions of this vibrant Nordic island. And be sure to keep an eye out for Yule Lads! ICELAND Europe | Reykjavik, Akureyri, Húsavík, Lake Mývatn Trip Overview 8 DAYS / 7 NIGHTS ACCOMMODATIONS 4 LOCATIONS Icelandair Hotel Reykjavik Reykjavik, Akureyri, Húsavík, Marina Lake Mývatn Icelandair Hotel Akureyri AGES FLIGHT INFORMATION 17 MEALS Minimum Age: 8 Arrive: Keflavík International 7 Breakfasts, 5 Lunches, 5 Suggested Age: 10+ Airport (KEF) Dinners Adult Exclusive: 18+ Return: Keflavík International Airport (KEF) ICELAND Europe | Reykjavik, Akureyri, Húsavík, Lake Mývatn DAY 1 REYKJAVIK Activities Highlights: Dinner Included Arrive in Reykjavik, Blue Lagoon Icelandair Hotel Reykjavik Marina Arrive in Reykjavik Velkomið (welcome) to Iceland! Fly into Keflavík International Airport (KEF), where you will be greeted by your driver who will take you to the Icelandair Hotel Reykjavik Marina. Check-In at Icelandair Hotel Reykjavik Marina As your Adventure Guides prepare for your 3:00 PM check-in, enjoy exploring this lively hotel with a whimsical feel. Notice the traditional Icelandic designs that references the island’s maritime culture – which is evident by its waterfront location. The hotel is walking distance from the quaint shops, restaurants, galleries and entertainment in the old harbor area. Welcome Reception at the Hotel Meet your fellow Adventurers and Adventure Guides before setting off for a relaxing visit to Blue Lagoon. -

Og Félagsvísindasvið Háskólinn Á Akureyri 2020

Policing Rural and Remote Areas of Iceland: Challenges and Realities of Working Outside of the Urban Centres Birta Dögg Svansdóttir Michelsen Félagsvísindadeild Hug- og félagsvísindasvið Háskólinn á Akureyri 2020 < Policing Rural and Remote Areas of Iceland: Challenges and Realities of Working Outside of the Urban Centres Birta Dögg Svansdóttir Michelsen 12 eininga lokaverkefni sem er hluti af Bachelor of Arts-prófi í lögreglu- og löggæslufræði Leiðbeinandi Andrew Paul Hill Félagsvísindadeild Hug- og félagsvísindasvið Háskólinn á Akureyri Akureyri, Maí 2020 Titill: Policing Rural and Remote Areas of Iceland Stuttur titill: Challenges and Realities of Working Outside of the Urban Centres 12 eininga lokaverkefni sem er hluti af Bachelor of Arts-prófi í lögreglu- og löggæslufræði Höfundarréttur © 2020 Birta Dögg Svansdóttir Michelsen Öll réttindi áskilin Félagsvísindadeild Hug- og félagsvísindasvið Háskólinn á Akureyri Sólborg, Norðurslóð 2 600 Akureyri Sími: 460 8000 Skráningarupplýsingar: Birta Dögg Svansdóttir Michelsen, 2020, BA-verkefni, félagsvísindadeild, hug- og félagsvísindasvið, Háskólinn á Akureyri, 39 bls. Abstract With very few exceptions, factual and fictionalized the portrayals of the police and law enforcement are almost always situated in urban settings. Only ‘real’ police work occurs in the cities while policing in rural and remote areas is often depicted as less critical, or in some cases non-existent. In a similar fashion, much of the current academic literature has focused on police work in urban environments. It is only in the past five years that the academic focus has turned its attention to the experiences of police officers who live and work in rural and remote areas. To date, no such studies have yet examined the work of police officers in rural and remote areas of Iceland. -

Celebrating the Establishment, Development and Evolution of Statistical Offices Worldwide: a Tribute to John Koren

Statistical Journal of the IAOS 33 (2017) 337–372 337 DOI 10.3233/SJI-161028 IOS Press Celebrating the establishment, development and evolution of statistical offices worldwide: A tribute to John Koren Catherine Michalopouloua,∗ and Angelos Mimisb aDepartment of Social Policy, Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, Athens, Greece bDepartment of Economic and Regional Development, Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, Athens, Greece Abstract. This paper describes the establishment, development and evolution of national statistical offices worldwide. It is written to commemorate John Koren and other writers who more than a century ago published national statistical histories. We distinguish four broad periods: the establishment of the first statistical offices (1800–1914); the development after World War I and including World War II (1918–1944); the development after World War II including the extraordinary work of the United Nations Statistical Commission (1945–1974); and, finally, the development since 1975. Also, we report on what has been called a “dark side of numbers”, i.e. “how data and data systems have been used to assist in planning and carrying out a wide range of serious human rights abuses throughout the world”. Keywords: National Statistical Offices, United Nations Statistical Commission, United Nations Statistics Division, organizational structure, human rights 1. Introduction limitations to this power. The limitations in question are not constitutional ones, but constraints that now Westergaard [57] labeled the period from 1830 to seemed to exist independently of any formal arrange- 1849 as the “era of enthusiasm” in statistics to indi- ments of government.... The ‘era of enthusiasm’ in cate the increasing scale of their collection. -

Discover Iceland Cruise August 23-30, 2022

DISCOVER ICELAND CRUISE AUGUST 23-30, 2022 DISCOVER ICELAND CRUISE AUGUST 23-30, 2022 on board Windstar’s Star Pride REYKJAVIC | SURTSEY ISLAND | HEIMAEY ISLAND | SEYDISFJORDUR | AKUREYRI | ISAFJORDUR | GRUNDARFJORDUR Isla Espiritu Santo DISCOVER ICELAND CRUISE AUGUST 23-30, 2022 Dramatic scenery and curious communities coalesce on this week-long circumnavigation of Iceland. Explore a country few people will ever visit, and go far beyond the tourist hotspots to remote fjords, raging waterfalls, hot springs and small fishing villages. Get to know the independent and creative Icelanders, and watch whales, Atlantic Puns, Arctic Terns and other seabirds play o shore. Join us on a Vacation Stretcher and witness the beauty of Gullfoss, Golden Waterfalls, step into a glacier or walk on the continental divide when visiting Thingvellir National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, or pay a visit to the famed natural spa ‘Blue Lagoon’ for a soak in the volcanic, mineral-rich heated waters. This is yachting at its most inventive. DISCOVER ICELAND CRUISE AUGUST 23-30, 2022 YOUR ITINERARY Tuesday, August 23, 2022 Reykjavik, Iceland Wednesday, August 24, 2022 Scenic Cruise Surtsey Island / Heimaey Island Thursday, August 25, 2022 Seydisfjordur Friday, August 26, 2022 Seydisfjordur Saturday, August 27, 2022 Akureyri Sunday, August 28, 2022 Isafjordur Monday, August 29, 2022 Grundarfjordur Tuesday, August 30, 2022 Reykjavik, Iceland DISCOVER ICELAND CRUISE AUGUST 23-30, 2022 INCLUDED • Accommodations for 8 days/7 nights on the recently refurbished, elegant -

Annex 3: Sources, Methods and Technical Notes

Annex 3 EAG 2007 Education at a Glance OECD Indicators 2007 Annex 3: Sources 1 Annex 3 EAG 2007 SOURCES IN UOE DATA COLLECTION 2006 UNESCO/OECD/EUROSTAT (UOE) data collection on education statistics. National sources are: Australia: - Department of Education, Science and Training, Higher Education Group, Canberra; - Australian Bureau of Statistics (data on Finance; data on class size from a survey on Public and Private institutions from all states and territories). Austria: - Statistics Austria, Vienna; - Federal Ministry for Education, Science and Culture, Vienna (data on Graduates); (As from 03/2007: Federal Ministry for Education, the Arts and Culture; Federal Ministry for Science and Research) - The Austrian Federal Economic Chamber, Vienna (data on Graduates). Belgium: - Flemish Community: Flemish Ministry of Education and Training, Brussels; - French Community: Ministry of the French Community, Education, Research and Training Department, Brussels; - German-speaking Community: Ministry of the German-speaking Community, Eupen. Brazil: - Ministry of Education (MEC) - Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) Canada: - Statistics Canada, Ottawa. Chile: - Ministry of Education, Santiago. Czech Republic: - Institute for Information on Education, Prague; - Czech Statistical Office Denmark: - Ministry of Education, Budget Division, Copenhagen; - Statistics Denmark, Copenhagen. 2 Annex 3 EAG 2007 Estonia - Statistics office, Tallinn. Finland: - Statistics Finland, Helsinki; - National Board of Education, Helsinki (data on Finance). France: - Ministry of National Education, Higher Education and Research, Directorate of Evaluation and Planning, Paris. Germany: - Federal Statistical Office, Wiesbaden. Greece: - Ministry of National Education and Religious Affairs, Directorate of Investment Planning and Operational Research, Athens. Hungary: - Ministry of Education, Budapest; - Ministry of Finance, Budapest (data on Finance); Iceland: - Statistics Iceland, Reykjavik. -

ICT Statistics at the New Millennium – Developing Official Statistics – Measuring the Diffusion of ICT and Its Impacts

IAOS Satellite Meeting on Statistics for the Information Society August 30 and 31, 2001, Tokyo, Japan ICT Statistics at the New Millennium – Developing Official Statistics – Measuring the Diffusion of ICT and its Impacts JESKANEN-SUNDSTRÖM, Heli Statistics Finland, Finland 1. Introduction Over the past few years, compilers of statistics the world over have been forced to realise that the descriptive systems used in statistics are not keeping up with the pace of social and economic change. The internationalisation of economies, glo balisation, the rapid advance of the new technology, changes in production structures, business reorganisation and so forth all place increasing pressure on the national statistical systems. As the importance of the intangible economy grows, the foundation of the traditional compiling of statistics, based on readily identifiable and measurable parameters, is being eroded. The more complex economic phenomena and linkages become, the greater and more specific will be the needs of the users of statistics. The potential of statistical organisations to respond to these new challenges varies from one country to another. The countries with the most sophisticated statistical systems are currently making a concerted effort to find new statistical standards that would be more appropriate than those currently in use to describe the information society. At the same time, however, many countries are still struggling to establish statistics for the services sector or to develop labour force surveys. Section 2 gives a short and very rough overview of the ongoing work in the field of statistics relating to the development of information and communication technology (ICT) and its impacts on the economies and on the society as a whole. -

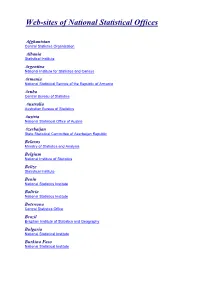

Web-Sites of National Statistical Offices

Web-sites of National Statistical Offices Afghanistan Central Statistics Organization Albania Statistical Institute Argentina National Institute for Statistics and Census Armenia National Statistical Service of the Republic of Armenia Aruba Central Bureau of Statistics Australia Australian Bureau of Statistics Austria National Statistical Office of Austria Azerbaijan State Statistical Committee of Azerbaijan Republic Belarus Ministry of Statistics and Analysis Belgium National Institute of Statistics Belize Statistical Institute Benin National Statistics Institute Bolivia National Statistics Institute Botswana Central Statistics Office Brazil Brazilian Institute of Statistics and Geography Bulgaria National Statistical Institute Burkina Faso National Statistical Institute Cambodia National Institute of Statistics Cameroon National Institute of Statistics Canada Statistics Canada Cape Verde National Statistical Office Central African Republic General Directorate of Statistics and Economic and Social Studies Chile National Statistical Institute of Chile China National Bureau of Statistics Colombia National Administrative Department for Statistics Cook Islands Statistics Office Costa Rica National Statistical Institute Côte d'Ivoire National Statistical Institute Croatia Croatian Bureau of Statistics Cuba National statistical institute Cyprus Statistical Service of Cyprus Czech Republic Czech Statistical Office Denmark Statistics Denmark Dominican Republic National Statistical Office Ecuador National Institute for Statistics and Census Egypt -

Quality Work Within Statistics

▲ EDITION 1999 Quality Work and Quality Assurance within Statistics EUROPEAN THEME 0 COMMISSION 0Miscellaneous 2 FOREWORD Statistics & quality go hand-in-hand Quality of statistics was the theme of the annual conference of presidents and directors-general of the national sta- tistical institutes (NSIs) of EU and EEA countries, organised in Stockholm on 28-29 May 1998 by Statistics Sweden in collaboration with Eurostat. Quality has always been one of the obvious requirements of statistics, although the notion of 'quality' has changed over the years. Nowadays a statistical 'product' has to exhibit reliability, relevance of concept, promptness, ease of access, clarity, comparability, consistency and exhaustiveness. While all these features form part of the whole prod- uct, individual users will attach more or less importance to each one. When statistics - gross domestic product or inflation, for example - have a financial impact, accuracy and comparability are vital. But if the same data are being used by someone interested in short-term trends, then the speed with which they are made available is the key feature. It is for users to decide. They are the people who determine quality criteria. Statisticians are no longer 'number freaks' in a world of their own, but have become managers of statistics, in constant touch with those who make decisions. Such a transformation is possible only if the whole production process is ready for change, because, as a rule, sci- entists such as statisticians tend not to pay much attention to the needs of people outside their own world. Scientists prefer to talk to other scientists. Now that the need for change is understood, how to bring it about? This question is being addressed by most of those in charge of national statistical institutes. -

Women and Men in Iceland 2018

Influence and Power Wages and Income Women as percentage of candidates and elected members in % parliamentary elections 1987–2017 % The unadjusted gender pay gap 2008–2016 Women and Men 60 25 in Iceland 2018 50 20 15 40 Population 10 30 Population by sex and age 1950 and 2017 Age 5 20 100 Women Men 90 0 2017: 167,316 2017: 171,033 10 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 80 Total Full-time 70 0 Note: (Men´s hourly earnings - women´s hourly earnings)/men´s hourly earnings. Overtime payments and overtime 1987 1991 1995 1999 2003 2007 2009 hours are included in the GPG. The gender pay gap indicator has been dened as unadjusted i.e. not adjusted 2013 2016 2017 60 according to individual characteristics that may explain part of the earnings like occupation, education, age, years 2017 Candidates Elected members with employer etc. 50 Women´s share of leadership in enterprises by size of Average income from work by region 2016 40 Million ISK 1950 % enterprise 2016 30 60 7 1950 20 50 6 10 40 5 0 4 30 3,000 2,000 1,000 0 1,000 2,000 3,000 3 6.4 20 5.9 2 4.8 Population 2016 10 4.0 1 0 Women Men 1– 49 50– 99 100– 249 250+ 0 Number of employees Women Men Women Men Mean population 166,288 169,152 Capital region Other regions Managers Chairpersons Board of directors 0–14 years, % 20 20 Note: Annual wages and other work related income of those who have some income from work. -

Direct Use of Geothermal Water for District Heating in Reykjavík And

Proceedings World Geothermal Congress 2010 Bali, Indonesia, 25-29 April 2010 Direct Use of Geothermal Water for District Heating in Reykjavík and Other Towns and Communities in SW-Iceland Einar Gunnlaugsson, Gretar Ívarsson Reykjavík Energy, Bæjarháls 1, 110 Reykjavík, Iceland [email protected] Keywords: Direct use, District heating, Reykjavík, Iceland 3. GEOTHERMAL WATER FOR HOUSE HEATING In the Icelandic sagas, which were written in the 12th – ABSTRACT 13th century A.D., bathing in hot springs is often The geothermal district heating utility in Reykjavík is the mentioned. Commonly bath was taken in brocks where hot world´s largest geothermal district heating service. It started water from often boiling springs would be mixed with cold on a small scale in 1930 and today it serves the capital of water. The famous saga writer Snorri Sturluson lived at Reykjavík and surrounding communities, about 58 % of the Reykholt in west Iceland in the 13th century. At that time total population of Iceland. All houses in this area are there was a bath at his farm but no information about its heated with geothermal water. Three low-temperature age, size or structure. There are also implications that fields, Laugarnes, Elliðaaár and Reykir/Reykjahlíð are used geothermal water or steam was directed to the house for for this purpose along with geothermal water from the high- heating (Sveinbjarnardóttir 2005). temperature field at Nesjavellir. Reykjavík Energy is also operating district heating utilities in 7 other towns outside In a cold country like Iceland, home heating needs are the capital area with total 15.000 thousand inhabitants and 7 greater than in most countries.