Repository . Ust . Hk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pro-Poor Policy Processes and Institutions: a Political Economic Discussion

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION AND GLOBALIZATION: ENHANCING PUBLIC-PRIVATE COLLABORATION IN PUBLIC SERVICE DELIVERY New Delhi, India 7 October 2003 In cooperation with the Eastern Regional Organization for Public Administration United Nations Division for Public Administration and Development Management Department of Economic and Social Affairs Public Administration and Globalization: Enhancing Public-Private Collaboration in Public Service Delivery New Delhi, India 7 October 2003 In cooperation with the Eastern Regional Organization for Public Administration United Nations New York The opinions expressed herein are the responsibilities of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations nor the Eastern Regional Organization for Public Administration All rights reserved. Table of Contents Foreword Pro-Poor Policy Processes and Institutions: A Political Economic Discussion . 1 M. ADIL KHAN The Dilemma of Governance in Latin America . 16 JOSE GPE. VARGAS HERNANDEZ Institutional Mechanisms for Monitoring International Commitments to Social Development: The Philippine Experience . 26 MA. CONCEPCION P. ALFILER Globalization and Social Development: Capacity Building for Public-Private Collaboration for Public Service Delivery . 55 AMARA PONGSAPICH Trade Liberalization and the Poor: A Framework for Poverty Reduction Policies with Special Reference to Some Asian Countries including India . 76 SOMESH K. MATHUR Government and Basic Sector Engagement in Poverty Alleviation: Highlights of a Survey . 118 VICTORIA A. BAUTISTA Private Sector Participation in Education Services . 132 MALATHI SOMAIAH Enhancing Public-Private Sector Collaboration in Public Service Delivery: The Malaysian Perspective . 142 VASANTHA DAISY RUTH CHARLES Public-Private Collaboration in Public Service Delivery: Hong Kong’s Experience . 149 JERMAIN T.M. LAM Gender Policies and Responses Towards Greater Women Empowerment in the Philippines . -

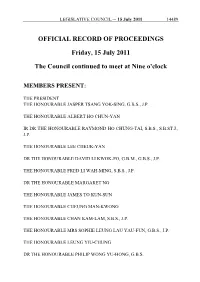

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Friday, 15 July

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 15 July 2011 14489 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Friday, 15 July 2011 The Council continued to meet at Nine o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. 14490 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 15 July 2011 THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, M.H. -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)220/11-12 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB2/PL/SE Panel on Security Minutes of meeting held on Tuesday, 12 April 2011, at 4:30 pm in Conference Room A of the Legislative Council Building Members : Hon James TO Kun-sun (Chairman) present Hon LAU Kong-wah, JP (Deputy Chairman) Hon Albert HO Chun-yan Dr Hon Margaret NG Dr Hon Philip WONG Yu-hong, GBS Hon WONG Yung-kan, SBS, JP Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon Abraham SHEK Lai-him, SBS, JP Hon Audrey EU Yuet-mee, SC, JP Hon Andrew LEUNG Kwan-yuen, GBS, JP Hon CHIM Pui-chung Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan Dr Hon LAM Tai-fai, BBS, JP Hon WONG Kwok-kin, BBS Dr Hon PAN Pey-chyou Hon Paul TSE Wai-chun Hon LEUNG Kwok-hung Hon WONG Yuk-man Members : Hon CHEUNG Man-kwong absent Hon Timothy FOK Tsun-ting, GBS, JP Hon CHAN Hak-kan Hon IP Kwok-him, GBS, JP - 2 - Public Officers : Item IV attending The Administration Mr LAI Tung-kwok, SBS, IDSM, JP Under Secretary for Security Mr CHOW Wing-hang Principal Assistant Secretary for Security Mr LEUNG Kwok-hung Assistant Director (Enforcement and Torture Claim Assessment) Immigration Department Item V The Administration Mr LAI Tung-kwok, SBS, IDSM, JP Under Secretary for Security Mrs Millie NG Principal Assistant Secretary for Security Mr YU Mun-sang Chief Superintendent Crime Wing Headquarters Hong Kong Police Force Mr TANG Ping-keung Senior Superintendent Crime Wing Headquarters Hong Kong Police Force Attendance : Item IV by invitation Duty Lawyer Service Ms Grace WONG Hong Kong Bar Association Mr Kumar RAMANATHAN, SC Mr P Y LO - 3 - The Law Society of Hong Kong Mr Lester HUANG Chairman Mr Mark DALY Society for Community Organization Ms Annie LIN Community Organizer Mr Richard TSOI Community Organizer Clerk in : Mr Raymond LAM attendance Chief Council Secretary (2) 1 Staff in : Ms Connie FUNG attendance Senior Assistant Legal Adviser 1 Mr Ian CHOW Senior Council Secretary (2) 1 Miss Lulu YEUNG Clerical Assistant (2) 1 Action I. -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration) Administration) Panel on Constitutional Affairs

立法會 Legislative Council Ref : CB2/PL/CA LC Paper No. CB(2)1659/13-14 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Administration) Panel on Constitutional Affairs Minutes of special meeting held on Saturday, 18 January 2014, at 9:00 am in Conference Room 1 of the Legislative Council Complex Members : Hon TAM Yiu-chung, GBS, JP (Chairman) present Hon Paul TSE Wai-chun, JP (Deputy Chairman) Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon Jeffrey LAM Kin-fung, GBS, JP Hon Starry LEE Wai-king, JP Hon CHAN Kin-por, BBS, JP Dr Hon Priscilla LEUNG Mei-fun, SBS, JP Hon WONG Kwok-kin, BBS Hon IP Kwok-him, GBS, JP Hon Alan LEONG Kah-kit, SC Hon WONG Yuk-man Hon Michael TIEN Puk-sun, BBS, JP Hon James TIEN Pei-chun, GBS, JP Hon NG Leung-sing, SBS, JP Hon Steven HO Chun-yin Hon YIU Si-wing Hon MA Fung-kwok, SBS, JP Hon Charles Peter MOK Hon CHAN Chi-chuen Dr Hon Kenneth CHAN Ka-lok Hon CHAN Yuen-han, SBS, JP Hon Dennis KWOK Hon Christopher CHEUNG Wah-fung, JP Hon SIN Chung-kai, SBS, JP Dr Hon Helena WONG Pik-wan Hon IP Kin-yuen Dr Hon CHIANG Lai-wan, JP Hon CHUNG Kwok-pan Hon Tony TSE Wai-chuen - 2 - Members : Hon Albert HO Chun-yan absent Hon LEE Cheuk-yan Dr Hon LAU Wong-fat, GBM, GBS, JP Hon Frederick FUNG Kin-kee, SBS, JP Hon WONG Ting-kwong, SBS, JP Hon Ronny TONG Ka-wah, SC Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan Dr Hon LAM Tai-fai, SBS, JP Hon Mrs Regina IP LAU Suk-yee, GBS, JP Hon LEUNG Kwok-hung Hon Gary FAN Kwok-wai Hon Alice MAK Mei-kuen, JP Hon Martin LIAO Cheung-kong, JP Public Officers : Sessions One to Three attending Mr LAU Kong-wah Under Secretary for Constitutional -

To Read the Full Briefing

HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION IN HONG KONG: HONG KONG WATCH BRIEFING ON EVENTS: MAY 2021 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This briefing describes developments in Hong Kong in the last month focusing on the rapid deterioration of human rights in the city following the introduction of the National Security Law in July. POLITICAL PRISONERS: ARRESTS, CHARGES, & TRIALS • Throughout May 2021, Beijing has continued its crackdown on the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong, with: o the jailing of ten prominent pro-democracy leaders for participating in a peaceful assembly, o the sentencing of Joshua Wong and three pro-democracy activists for their participation in last year’s June 4 vigil, o the banning of this year’s annual June 4 vigil, o the arrest of six protestors for marking the June 4 vigil, the arrest and charging of two pro-democracy activists for ‘sedition’, o the denial of bail to the former pro-democracy lawmaker Claudia Mo on the grounds of correspondence with foreign journalists, o and the decision to move the national security trial of the 47 pro-democracy activists to the High Court to allow the prosecutors to pursue the harshest sentence possible - life in prison. MOVES TO CONTINUE THE CRACKDOWN ON BASIC RIGHTS • In the last month, the Hong Kong Government and Beijing have moved to continue their crackdown on basic rights, with: o the Hong Kong Police freezing the assets of Jimmy Lai amounting to HK$500m, o the Hong Kong’s High Court ruling that rights-based constitutional challenges cannot be applied to the National Security Law, o the Hong Kong Police Commissioner warning that “publishing fake news” could breach the National Security Law, o Beijing expanding its presence in Hong Kong with new departments for national security and propaganda, o and the Hong Kong Government introducing a new regulation forcing Hong Kongers to register their identity when buying pre-paid mobile phone sim cards. -

VI. Developments in Hong Kong and Macau

VI. Developments in Hong Kong and Macau Findings • During the Commission’s reporting year, a number of deeply troubling developments in Hong Kong undermined the ‘‘one country, two systems’’ governance framework, which led the U.S. Secretary of State to find that Hong Kong has not main- tained a high degree of autonomy for the first time since the handover in July 1997. • On June 30, 2020, the National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC) passed the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Safeguarding National Security in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (National Security Law), by- passing Hong Kong’s Legislative Council. To the extent that this law criminalizes secession, subversion, terrorist activities, and collusion with foreign states, this piece of legislation vio- lates Hong Kong’s Basic Law, which specifies that Hong Kong shall pass laws concerning national security. Additionally, the National Security Law raises human rights and rule of law concerns because it violates principles such as the presumption of innocence and because it contains vaguely defined criminal offenses that can be used to unduly restrict fundamental free- doms. • The Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (PRC Liaison Office) declared in April 2020 that neither it nor the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office, both being State Council agencies, were subject to Article 22 of the Basic Law—a provision designed to protect Hong Kong’s high degree of autonomy. The Hong Kong government had long interpreted the provision to cover the PRC Liaison Office, but it reversed itself overnight in an ap- parent attempt to conform its position to that of the central government. -

Grenville Cross Says All of Those Who Were Complicit in RTHK Continues Protest-Related Crimes Must Expect to Face Consequences

| Monday, March 22, 2021 8 CHINA DAILY | HONG KONG EDITION Tuesday, June 1, 2021 | 9 COMMENTHK Strong punishments are a Ho Lok-sang The author is a senior research fellow at the Pan Sutong Shanghai-Hong fi tting coda to lawless era Kong Economic Policy Research Institute, Lingnan University. Grenville Cross says all of those who were complicit in RTHK continues protest-related crimes must expect to face consequences n May 28, 10 well-known “Beijing” played a part in the prosecution, to serve SAR’s defendants, who had ear- this shows his capacity for self-delusion and lier pleaded guilty to orga- misleading others is boundless. Under the nizing an unauthorized Basic Law, the Department of Justice controls criminal prosecutions “free from any interfer- public interest assembly on Oct 1, 2019, received their just deserts, ence” (Art.63), and, given that this was an and were sentenced to Grenville Cross open-and-shut case, its prosecutors would terms of imprisonment which ranged from 14 The author is a senior counsel, law profes- have had no di culty in concluding that ast week I read an interesting article by Professor Joseph sor and criminal justice analyst, and was to 18 months (DCCC 534/2020). Two of them, prosecutions were appropriate. The sentence Man Chan, professor emeritus of journalism and communi- O previously the director of public prosecu- for organizing an unauthorized assembly however, Richard Tsoi Yiu-cheong and Sin tions of the Hong Kong SAR. cation at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. His article, Chung-kai, had their sentences suspended, was, moreover, never “a fi xed-penalty fi ne”, published in Ming Pao, was headlined “RTHK turning into because of mitigating factors, including their and the courts have always enjoyed a wide La mouthpiece goes against the public interest”. -

Human Rights Defenders in Hong Kong Face New Charges for Tiananmen Vigil

10 August 2020 Statement: Human rights defenders in Hong Kong face new charges for Tiananmen vigil On 6 August 2020, the Hong Kong police brought new charges against 24 pro-democracy activists1 and human rights defenders for organising or participating in an annual vigil on 4 June 2020 to commemorate the 1989 massacre in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. On 3 and 4 June 1989, Chinese troops opened fire on p eaceful protesters who had assembled in great numbers in the capital to call for political and economic reforms, killing hundreds and possibly thousands. After 31 years, no one has been held accountable for these killings despite repeated demands from families and civil society. Front Line Defenders considers all those who peacefully advocate for truth, accountability, and reparations for the massacre, including through commemorative acts, to be human rights defenders. Among the 24 activists facing new charges, 11 are affiliated with the pro-democracy advocacy group Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements in China, which has been organising the vigil since 1990. The other 13 activists include civil society group leaders, current and former Legislative Council or District Council members, and student and youth activists. Of the 24 human rights defenders, 13 were already charged in June for “inciting others to participate in unauthorised assemblies” in relation to the Tiananmen vigil. On 6 August, all 24 were charged with “knowingly participating in an unauthorised assembly”, while one also faces an additional new charge of “holding an unauthorised assembly”. Six of the 24 defenders were also among the 15 pro-democracy activists and human rights defenders charged in April 2020 with “organising and participating in unlawful assemblies” for protests that took place in August and October 2019. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2011 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate Mar 15 2010 19:28 Oct 07, 2011 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\AR11FIN.TXT DEIDRE 2011 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate Mar 15 2010 19:28 Oct 07, 2011 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 U:\DOCS\AR11FIN.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2011 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 68–442 PDF WASHINGTON : 2011 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 19:28 Oct 07, 2011 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\AR11FIN.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey, SHERROD BROWN, Ohio, Cochairman Chairman MAX BAUCUS, Montana CARL LEVIN, Michigan DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon SUSAN COLLINS, Maine JAMES RISCH, Idaho EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS SETH D. HARRIS, Department of Labor MARIA OTERO, Department of State FRANCISCO J. SA´ NCHEZ, Department of Commerce KURT M. -

HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY HONG KONG 15 Activists Appear in Court for Roles in Illegal Assemblies

4 | Tuesday, May 19, 2020 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY HONG KONG 15 activists appear in court for roles in illegal assemblies By CHEN ZIMO in Hong Kong ed on Feb 28 for violating Hong [email protected] Kong’s Public Order Ordinance by participating in an unauthorized A group of 15 opposition fi gures, assembly between Wan Chai and including media tycoon Jimmy Lai Central on Aug 31. The case was Chee-ying, appeared in court on fi rst brought to court on May 5. Monday for their roles in violent Lai and other 14 activists were protests in Hong Kong last year. also arrested on April 18 on suspi- They faced charges of inciting, cion of organizing and participat- organizing, and participating in ing in subsequent unlawful assem- multiple unauthorized assemblies blies on Aug 18, Sept 30, Oct 1, Oct from August to October. 19, and Oct 20. The events were Lai, 72, founder of Hong Kong- grouped into three cases and fi rst based newspaper Apple Daily, heard in court on Monday. was charged with five counts of Principal Magistrate at the West three unauthorized assemblies. Kowloon Magistrates’ Courts Peter He was suspected of organizing Law Tak-chuen adjourned all the and participating in unauthorized cases until June 15. The defen- assemblies on Aug 18 and Oct 1, dants were granted cash bail of and joining another unauthorized HK$1,000 ($129). assembly on Aug 31. Lai was also charged with one Lawmakers cast their votes at the legislative council chamber on Monday to elect the chairperson of the LegCo’s House Committee after Each of the o enses, once con- count of “criminal intimidation” seven months of failing to do so due to the opposition camp’s delaying tactics. -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration) Ref : CB1/PL/EDEV/1

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(1)47/14-15 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB1/PL/EDEV/1 Panel on Economic Development Minutes of special meeting held on Monday, 12 May 2014, at 10:45 am in Conference Room 3 of the Legislative Council Complex Members present : Hon James TIEN Pei-chun, GBS, JP (Chairman) Hon Jeffrey LAM Kin-fung, GBS, JP (Deputy Chairman) Hon CHAN Kam-lam, SBS, JP Hon Andrew LEUNG Kwan-yuen, GBS, JP Hon WONG Ting-kwong, SBS, JP Hon Ronny TONG Ka-wah, SC Dr Hon LAM Tai-fai, SBS, JP Dr Hon LEUNG Ka-lau Hon Paul TSE Wai-chun, JP Hon Albert CHAN Wai-yip Hon Steven HO Chun-yin Hon Frankie YICK Chi-ming Hon YIU Si-wing Hon Charles Peter MOK Hon CHAN Han-pan Hon Kenneth LEUNG Hon Dennis KWOK Hon Christopher CHEUNG Wah-fung, JP Dr Hon Fernando CHEUNG Chiu-hung Hon SIN Chung-kai, SBS, JP Dr Hon Elizabeth QUAT, JP Hon TANG Ka-piu Hon CHUNG Kwok-pan Members attending : Hon WU Chi-wai, MH Dr Hon Kenneth CHAN Ka-lok Ir Dr Hon LO Wai-kwok, BBS, MH, JP Hon Tony TSE Wai-chuen - 2 - Public officers : Agenda Item I attending Mr WONG Kam-sing, JP Secretary for the Environment Ms Christine LOH Kung-wai, JP Under Secretary for the Environment Mr Vincent LIU Ming-kwong, JP Deputy Secretary for the Environment Mr Donald NG Man-kit Principal Assistant Secretary for the Environment (Electricity Reviews) Ms Vyora YAU Siu-man Principal Assistant Secretary for the Environment (Financial Monitoring) Attendance by : Agenda Item I invitation The Association of Hong Kong Professionals Ir Dr CHAN Fuk-cheung Vice Chairman -

The Protestant Missionaries As Bible Translators

THE PROTESTANT MISSIONARIES AS BIBLE TRANSLATORS: MISSION AND RIVALRY IN CHINA, 1807-1839 by Clement Tsz Ming Tong A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Religious Studies) UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) July 2016 © Clement Tsz Ming Tong, 2016 ABSTRACT The first generation of Protestant missionaries sent to the China mission, such as Robert Morrison and William Milne, were mostly translators, committing most of their time and energy to language studies, Scripture translation, writing grammar books and compiling dictionaries, as well as printing and distributing bibles and other Christian materials. With little instruction, limited resources, and formidable tasks ahead, these individuals worked under very challenging and at times dangerous conditions, always seeking financial support and recognition from their societies, their denominations and other patrons. These missionaries were much more than literary and linguistic academics – they operated as facilitators of the whole translational process, from research to distribution; they were mission agents in China, representing the interests and visions of their societies and patrons back home. Using rare Chinese Bible manuscripts, including one that has never been examined before, plus a large number of personal correspondence, journals and committee reports, this study seeks to understand the first generation of Protestant missionaries in their own mission settings, to examine the social fabrics within which they operated as “translators”, and to determine what factors and priorities dictated their translation decisions and mission strategies. Although Morrison is often credited with being the first translator of the New Testament into Chinese, the truth of the matter is far more complex.