VOlume 20 • ISsue 8 • MAy 1, 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pro-Poor Policy Processes and Institutions: a Political Economic Discussion

PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION AND GLOBALIZATION: ENHANCING PUBLIC-PRIVATE COLLABORATION IN PUBLIC SERVICE DELIVERY New Delhi, India 7 October 2003 In cooperation with the Eastern Regional Organization for Public Administration United Nations Division for Public Administration and Development Management Department of Economic and Social Affairs Public Administration and Globalization: Enhancing Public-Private Collaboration in Public Service Delivery New Delhi, India 7 October 2003 In cooperation with the Eastern Regional Organization for Public Administration United Nations New York The opinions expressed herein are the responsibilities of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations nor the Eastern Regional Organization for Public Administration All rights reserved. Table of Contents Foreword Pro-Poor Policy Processes and Institutions: A Political Economic Discussion . 1 M. ADIL KHAN The Dilemma of Governance in Latin America . 16 JOSE GPE. VARGAS HERNANDEZ Institutional Mechanisms for Monitoring International Commitments to Social Development: The Philippine Experience . 26 MA. CONCEPCION P. ALFILER Globalization and Social Development: Capacity Building for Public-Private Collaboration for Public Service Delivery . 55 AMARA PONGSAPICH Trade Liberalization and the Poor: A Framework for Poverty Reduction Policies with Special Reference to Some Asian Countries including India . 76 SOMESH K. MATHUR Government and Basic Sector Engagement in Poverty Alleviation: Highlights of a Survey . 118 VICTORIA A. BAUTISTA Private Sector Participation in Education Services . 132 MALATHI SOMAIAH Enhancing Public-Private Sector Collaboration in Public Service Delivery: The Malaysian Perspective . 142 VASANTHA DAISY RUTH CHARLES Public-Private Collaboration in Public Service Delivery: Hong Kong’s Experience . 149 JERMAIN T.M. LAM Gender Policies and Responses Towards Greater Women Empowerment in the Philippines . -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

商標註冊限期屆滿trade Mark Registrations Expired

公報編號 Journal No.: 773 公布日期 Publication Date: 26-01-2018 分項名稱 Section Name: 商標註冊限期屆滿 Trade Mark Registrations Expired 香港特別行政區政府知識產權署商標註冊處 Trade Marks Registry, Intellectual Property Department The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region 商標註冊限期屆滿 下列商標註冊未有續期。 TRADE MARK REGISTRATIONS EXPIRED The following trade mark registrations have not been renewed. [111] [511] [180] [730] [740 / 750] 註冊編號 類別編號 註冊屆滿日期 擁有人姓名/名稱 擁有人的送達地址 Trade Mark Class No. Expiry Date Owner's Name Owner's Address for Service No. 19520471 33 21-01-2018 DIAGEO BRANDS B.V. ROUSE LEGAL 18/F., Golden Centre, 188 Des Voeux Road Central HONG KONG 19520531 5 21-01-2018 MERCK CONSUMER HASTINGS & CO. HEALTHCARE LIMITED 5th Floor, Gloucester Tower, The Landmark, 11 Pedder Street, Central, HONG KONG 19590628 25 21-01-2018 KINWAY GARMENTS KINWAY GARMENTS LIMITED LIMITED 19TH FLOOR, MONGKOK COMMERCIAL CENTRE, NO. 16 ARGYLE STREET, KOWLOON, HONG KONG. 19730735 25 19-01-2018 Jacques Vert Group MAYER BROWN JSM Limited 16TH-19TH FLOORS, PRINCE'S BUILDING, 10 CHATER ROAD, CENTRAL, HONG KONG. 19731456 5 22-01-2018 BOEHRINGER INGELHEIM DEACONS KG 5TH FLOOR, ALEXANDRA HOUSE, 18 CHATER ROAD, CENTRAL, HONG KONG 19750132 30 18-01-2018 BAKERY TRADEMARK Hung's Management Services Limited LIMITED Flat B, 2/F, Hop Hing Industrial Building, 704 Castle Peak Road, Hong Kong 19880306AA 7, 9, 11 23-01-2018 GOLDEN PROFIT LIMITED WENPING & CO. 17/F., TUNG WAI COMMERCIAL BLDG., 111 GLOUCESTER ROAD, HONG KONG. 1/26 公報編號 Journal No.: 773 公布日期 Publication Date: 26-01-2018 分項名稱 Section Name: 商標註冊限期屆滿 Trade Mark Registrations Expired 19880515 30 21-01-2018 Intercontinental Great WILKINSON & GRIST Brands LLC 6th Floor, Prince's Building, 10 Chater Road, Central HONG KONG 19880830 25 21-01-2018 KIAO KONG SHOES CO. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 2007 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 38–026 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER M. LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana TOM UDALL, New Mexico CARL LEVIN, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIM WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio CHRISTOPHER H. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual Report 2019

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2019 ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 18, 2019 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: https://www.cecc.gov VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:38 Nov 18, 2019 Jkt 036743 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 G:\ANNUAL REPORT\ANNUAL REPORT 2019\2019 AR GPO FILES\FRONTMATTER.TXT CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2019 ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 18, 2019 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: https://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 36–743 PDF WASHINGTON : 2019 VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:38 Nov 18, 2019 Jkt 036743 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 G:\ANNUAL REPORT\ANNUAL REPORT 2019\2019 AR GPO FILES\FRONTMATTER.TXT CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate JAMES P. MCGOVERN, Massachusetts, MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Co-chair Chair JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio TOM COTTON, Arkansas THOMAS SUOZZI, New York STEVE DAINES, Montana TOM MALINOWSKI, New Jersey TODD YOUNG, Indiana BEN MCADAMS, Utah DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California CHRISTOPHER SMITH, New Jersey JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon BRIAN MAST, Florida GARY PETERS, Michigan VICKY HARTZLER, Missouri ANGUS KING, Maine EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Department of State, To Be Appointed Department of Labor, To Be Appointed Department of Commerce, To Be Appointed At-Large, To Be Appointed At-Large, To Be Appointed JONATHAN STIVERS, Staff Director PETER MATTIS, Deputy Staff Director (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:38 Nov 18, 2019 Jkt 036743 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 G:\ANNUAL REPORT\ANNUAL REPORT 2019\2019 AR GPO FILES\FRONTMATTER.TXT C O N T E N T S Page I. -

Volume 20 • Issue 4 • February 28, 2020

VOLUME 20 • ISSUE 4 • FEBRUARY 28, 2020 IN THIS ISSUE: Beijing Purges Wuhan: The CCP Central Authorities Tighten Political Control Over Hubei Province By John Dotson……………………………………………………pp. 1-6 Beijing’s Appointment of Xia Baolong Signals a Harder Line on Hong Kong By Willy Lam………………………………………………………...pp. 7-11 Fair-Weather Friends: The Impact of the Coronavirus on the Strategic Partnership Between Russia and China By Johan van de Ven………………………………………………...pp. 12-16 The PRC’s Cautious Stance on the U.S. Indo-Pacific Strategy By Yamazaki Amane…………………………………………………pp. 17-22 China’s Declining Birthrate and Changes in CCP Population Policies By Linda Zhang…………………………………………………….…pp. 23-28 Beijing Purges Wuhan: The CCP Central Authorities Tighten Political Control Over Hubei Province John Dotson Introduction: The CCP Center Presses a Positive Narrative About Its Response to COVID-19 Following a slow reaction to the initial outbreak of the COVID-19 virus, since late January the zhongyang (中 央), or central authorities, of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) have conducted a concerted public relations effort to present themselves as actively engaged in directing efforts to combat the epidemic. This has included the creation of a new senior-level CCP “leading small group” focused on the epidemic (China Brief, February 5), and a messaging campaign to assert that CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping has been personally “commanding China’s fight” against the outbreak (Xinhua, February 2). Senior officials have also made a range 1 ChinaBrief • Volume 20 • Issue 4 • February 28, 2020 of recent public appearances intended to demonstrate zhongyang concern for, and control over, the campaign against the epidemic. -

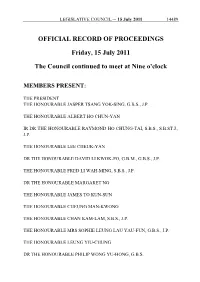

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Friday, 15 July

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 15 July 2011 14489 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Friday, 15 July 2011 The Council continued to meet at Nine o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. 14490 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 15 July 2011 THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, M.H. -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)220/11-12 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB2/PL/SE Panel on Security Minutes of meeting held on Tuesday, 12 April 2011, at 4:30 pm in Conference Room A of the Legislative Council Building Members : Hon James TO Kun-sun (Chairman) present Hon LAU Kong-wah, JP (Deputy Chairman) Hon Albert HO Chun-yan Dr Hon Margaret NG Dr Hon Philip WONG Yu-hong, GBS Hon WONG Yung-kan, SBS, JP Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon Abraham SHEK Lai-him, SBS, JP Hon Audrey EU Yuet-mee, SC, JP Hon Andrew LEUNG Kwan-yuen, GBS, JP Hon CHIM Pui-chung Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan Dr Hon LAM Tai-fai, BBS, JP Hon WONG Kwok-kin, BBS Dr Hon PAN Pey-chyou Hon Paul TSE Wai-chun Hon LEUNG Kwok-hung Hon WONG Yuk-man Members : Hon CHEUNG Man-kwong absent Hon Timothy FOK Tsun-ting, GBS, JP Hon CHAN Hak-kan Hon IP Kwok-him, GBS, JP - 2 - Public Officers : Item IV attending The Administration Mr LAI Tung-kwok, SBS, IDSM, JP Under Secretary for Security Mr CHOW Wing-hang Principal Assistant Secretary for Security Mr LEUNG Kwok-hung Assistant Director (Enforcement and Torture Claim Assessment) Immigration Department Item V The Administration Mr LAI Tung-kwok, SBS, IDSM, JP Under Secretary for Security Mrs Millie NG Principal Assistant Secretary for Security Mr YU Mun-sang Chief Superintendent Crime Wing Headquarters Hong Kong Police Force Mr TANG Ping-keung Senior Superintendent Crime Wing Headquarters Hong Kong Police Force Attendance : Item IV by invitation Duty Lawyer Service Ms Grace WONG Hong Kong Bar Association Mr Kumar RAMANATHAN, SC Mr P Y LO - 3 - The Law Society of Hong Kong Mr Lester HUANG Chairman Mr Mark DALY Society for Community Organization Ms Annie LIN Community Organizer Mr Richard TSOI Community Organizer Clerk in : Mr Raymond LAM attendance Chief Council Secretary (2) 1 Staff in : Ms Connie FUNG attendance Senior Assistant Legal Adviser 1 Mr Ian CHOW Senior Council Secretary (2) 1 Miss Lulu YEUNG Clerical Assistant (2) 1 Action I. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement May 2007 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC .......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 42 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 44 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 45 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 52 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 May 2007 The Main National Leadership of the PRC -

Insights Huining on the Liaison Office

The intriguing appointment of Luo Insights Huining on the Liaison Office In late December 2019, Luo Huining 骆惠宁 was set aside and taken down from his provincial position (Shanxi Party Secretary [2016-2019]) and instead sent, as several 65-year-old Cadres often do before their official retirement, to a commission led by the National People’s Congress (NPC). Luo, a provincial veteran (Anhui Standing Committee [1999-2003], Governor [2010-2013] and Party Secretary of Qinghai [2013-2016]), seemed then to follow in the footsteps of his Qinghai predecessor, Qiang Wei 强卫1. Replaced by Lou Yangsheng 楼阳生 – part of Xi’s Zhejiang “army”, Luo, despite being regarded as competent when it came to the anti-corruption campaign, has never shown any overt signs of siding with Xi. As such, the sudden removal of Wang Zhimin 王志民2 – now ex-director of the Hong Kong Liaison Office for the Central government, which, to be fair, was predictable3, became even more confusing when it became known that he would be replaced by Luo. Some are saying this “new” player could bring a breath of fresh air and bring new perspectives on the current state of affairs; some might see this move as either an ill-advised decision or the result of lengthy negotiations at the top – negotiations that might not have tilted in Xi’s favor. A fall from “grace” in the shadow of Zeng Qinghong Wang Zhimin’s removal, as previously stated, is almost a non-event, as Xi was (and still is) clearly dissatisfied with the way the Hong Kong - Macau affairs system 港澳系统 is dealing with the protests. -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration) Administration) Panel on Constitutional Affairs

立法會 Legislative Council Ref : CB2/PL/CA LC Paper No. CB(2)1659/13-14 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Administration) Panel on Constitutional Affairs Minutes of special meeting held on Saturday, 18 January 2014, at 9:00 am in Conference Room 1 of the Legislative Council Complex Members : Hon TAM Yiu-chung, GBS, JP (Chairman) present Hon Paul TSE Wai-chun, JP (Deputy Chairman) Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon Jeffrey LAM Kin-fung, GBS, JP Hon Starry LEE Wai-king, JP Hon CHAN Kin-por, BBS, JP Dr Hon Priscilla LEUNG Mei-fun, SBS, JP Hon WONG Kwok-kin, BBS Hon IP Kwok-him, GBS, JP Hon Alan LEONG Kah-kit, SC Hon WONG Yuk-man Hon Michael TIEN Puk-sun, BBS, JP Hon James TIEN Pei-chun, GBS, JP Hon NG Leung-sing, SBS, JP Hon Steven HO Chun-yin Hon YIU Si-wing Hon MA Fung-kwok, SBS, JP Hon Charles Peter MOK Hon CHAN Chi-chuen Dr Hon Kenneth CHAN Ka-lok Hon CHAN Yuen-han, SBS, JP Hon Dennis KWOK Hon Christopher CHEUNG Wah-fung, JP Hon SIN Chung-kai, SBS, JP Dr Hon Helena WONG Pik-wan Hon IP Kin-yuen Dr Hon CHIANG Lai-wan, JP Hon CHUNG Kwok-pan Hon Tony TSE Wai-chuen - 2 - Members : Hon Albert HO Chun-yan absent Hon LEE Cheuk-yan Dr Hon LAU Wong-fat, GBM, GBS, JP Hon Frederick FUNG Kin-kee, SBS, JP Hon WONG Ting-kwong, SBS, JP Hon Ronny TONG Ka-wah, SC Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan Dr Hon LAM Tai-fai, SBS, JP Hon Mrs Regina IP LAU Suk-yee, GBS, JP Hon LEUNG Kwok-hung Hon Gary FAN Kwok-wai Hon Alice MAK Mei-kuen, JP Hon Martin LIAO Cheung-kong, JP Public Officers : Sessions One to Three attending Mr LAU Kong-wah Under Secretary for Constitutional