Primary Pupillary Margin Cyst of the Iris Pigment Epithelium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Affections of Uvea Affections of Uvea

AFFECTIONS OF UVEA AFFECTIONS OF UVEA Anatomy and physiology: • Uvea is the vascular coat of the eye lying beneath the sclera. • It consists of the uvea and uveal tract. • It consists of 3 parts: Iris, the anterior portion; Ciliary body, the middle part; Choroid, the third and the posterior most part. • All the parts of uvea are intimately associated. Iris • It is spongy having the connective tissue stroma, muscular fibers and abundance of vessels and nerves. • It is lined anteriorly by endothelium and posteriorly by a pigmented epithelium. • Its color is because of amount of melanin pigment. Mostly it is brown or golden yellow. • Iris has two muscles; the sphincter which encircles the pupil and has parasympathetic innervation; the dilator which extends from near the sphincter and has sympathetic innervation. • Iris regulates the amount of light admitted to the interior through pupil. • The iris separates the anterior chamber from the posterior chamber of the eye. Ciliary Body: • It extends backward from the base of the iris to the anterior part of the choroid. • It has ciliary muscle and the ciliary processes (70 to 80 in number) which are covered by ciliary epithelium. Choroid: • It is located between the sclera and the retina. • It extends from the ciliaris retinae to the opening of the optic nerve. • It is composed mainly of blood vessels and the pigmented tissue., The pupil • It is circular and regular opening formed by the iris and is larger in dogs in comparison to man. • It contracts or dilates depending upon the light source, due the sphincter and dilator muscles of the iris, respectively. -

Posterior Uveal (Ciliary Body and Choroidal) Melanoma Leslie T

Posterior Uveal (Ciliary Body and Choroidal) Melanoma Leslie T. L. Pham, MD, Jordan M. Graff, MD, and H. Culver Boldt, MD July 27, 2010 Chief Complaint: 31-year-old man with "floaters and blurry vision" in the right eye (OD). History of Present Illness: In August 2007, a healthy 31-year-old truck driver from Nebraska started noticing floaters in his right eye. The floaters gradually worsened and clouded his central vision. His family doctor tried changing his blood pressure medications, but this did not help. He later saw an ophthalmologist in his home state who told him there was a "mass" in his right eye. He was referred to the University of Iowa Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences. Past Ocular History: The patient has had no prior eye surgery or trauma. Past Medical History: The patient reports prior excision of a benign skin nevus. He also has hypertension. Medications: Metoprolol and triamterene/hydrochlorothiazide Family History: The patient’s mother has a history of neurofibromatosis. His father had an enucleation for an "eye cancer" and subsequently died due to metastatic spread of the cancer. His grandmother had skin melanoma. Social History: The patient lives in Nebraska with his wife and child. He has never smoked and only drinks on "special occasions". Review of Systems: Negative, except as noted above. Ocular Examination: General: Well-developed, well-nourished Caucasian man in a pleasant mood Skin: Several scattered macules and papules on the trunk and all four extremities Distance visual acuity (without correction): o 20/60-2 OD o 20/20 OS Near acuity (without correction) o 20/30 OD o 20/20 OS Ocular motility: Full OU. -

Ophthalmic Pathology and Oncology A) Pathology

Ophthalmic pathology and oncology Objective Understanding the pathophysiology and oncology of the eye and in systemic diseases and their presentations. Differentiation of benign and malignant eye diseases, understanding the pathology and examination techniques with focus on the main risk factors of the disease. Recognising signs and symptoms of the disease with diagnostic tests at the slit lamp as well as functional and structural analysis. Management of presentation, including various therapeutic options (medical and surgical) and follow-up. Psychology and management of patients presenting with a potentially blinding and life-threatening disease. A) Pathology Anatomy and pathophysiology of: -Ocular anatomy and histology of the major structures of the eye and its adnexa: • Conjunctiva • Cornea • Sclera • Anterior chamber • Posterior chamber • Iris • Ciliary body • Lens • Vitreous • Retina and retinal pigment epithelium • Choroid • Optic nerve • Visual pathway • Eyelids • Extraocular muscles • Lacrimal system • Orbit Disease process • Congenital anomaly • Choristoma versus hamartoma Inflammation • Acute versus chronic • Focal versus diffuse • Granulomatus versus nongranulomatous Degeneration (includes dystrophy) Neoplasia • Benign versus malignant • Epithelial versus soft tissue versus haematopoietic -Basic pathophysiology of the common disease processes of the eye and its adnexa, and identify the major histologic findings: a. Degeneration (e.g., pterygium, keratoconus) b. Dystrophy (e.g., Fuchs’ dystrophy, TGFBI-associated dystrophies) c. Infection (e.g., fungal keratitis, bacterial endophthalmitis) d. Inflammation (e.g., chalazion, idiopathic orbital inflammation) e. Neoplasm and proliferation (e.g., basal and squamous cell carcinoma, uveal melanoma, retinoblastoma) - Pathophysiology and identify the major histologic findings of common diseases of the eye (e.g., keratitis, exfoliation syndrome, corneal and retinal dystrophies and degenerations, frequent neoplasms, oculoplastics, cornea, glaucoma, retina, ophthalmic oncology). -

Pigmented Iris Cyst in Vitreous Chamber Nimesh Patel,1 Rajeev Reddy Pappuru,1 Soumyava Basu,2 Mudit Tyagi1,2

BMJ Case Rep: first published as 10.1136/bcr-2020-239431 on 13 December 2020. Downloaded from Images in… Pigmented iris cyst in vitreous chamber Nimesh Patel,1 Rajeev Reddy Pappuru,1 Soumyava Basu,2 Mudit Tyagi1,2 1Smt Kanuri Santhamma Center DESCRIPTION Patient’s perspective for Vitreoretinal Diseases, LV A- 45- year old male patient, diagnosed elsewhere as Prasad Eye Institute, Hyderabad, retinal detachment, was seen in the retina services I had a black shadow moving in my eye, and Telangana, India of our institute. There was no history of prior 2Uveitis and Ocular Immunology after the surgery, my vision is more clear and the ocular trauma or surgery. His vision was 20/20 in Services, LV Prasad Eye Institute, shadow has gone. Hyderabad, India his right eye and 20/125 in the left eye. There were no signs of any ocular inflammation and the intra- Correspondence to ocular pressure was within normal limit. A retinal Dr Mudit Tyagi; evaluation revealed a free-floating pigmented Learning points drmudittyagi@ gmail. com cyst in vitreous cavity (figure 1,white arrow). A pars plana vitrectomy was done and the cyst was ► Congenital vitreous cysts may be remnants Accepted 22 October 2020 removed. The histopathology was suggestive of of the hyaloid vascular system such as iris pigment cells. The pigmented cells on the cyst Bergmeister’s papilla and Mittendorf’s dot wall are more likely to originate from the ciliary or may represent choristoma of the hyaloid pigment epithelium. The cysts initially are formed vascular system. on the ciliary body and then get dislodged into the ► Acquired cysts may be associated with vitreous, giving rise to the abrupt symptom of a trauma, uveitis, uveal colobomas and retinal diminution of vision. -

Iris Lymphocytic Lesion Mimicking Amelanotic Melanoma: a Clinico-Pathologic Case Report

Advances in Ophthalmology & Visual System Case Report Open Access Iris lymphocytic lesion mimicking amelanotic melanoma: a clinico-pathologic case report Abstract Volume 3 Issue 1 - 2015 Lymphoproliferative disorders of the iris are rare, they can be benign or malignant and Azza MY Maktabi,1 Mosa AlHarby,2 Hind only few cases have been reported in the literature. We have encountered a 70 year-old 3 male patient who developed an iris mass in his left eye over a period of 1 month. He Manaa Alkatan 1Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, King Khalid was referred to our tertiary eye care center with the provisional diagnosis of melanoma. Eye specialist Hospital, Saudi Arabia His clinical findings raised the suspicious of amelanotic melanoma because of the high 2Anterior Segment & Uveitis Divisions, King Khalid Eye specialist intraocular pressure in the involved eye, the noted vascularization of the mass, and the Hospital, Saudi Arabia anterior segment findings. The histopathological diagnosis of a T-cell rich lymphocytic 3Department of Ophthalmology, College of Medicine, King Saud lesion was not suspected. The clinicopathologic findings of this case are described with University, Saudi Arabia brief specific review of the literature on the topic of lymphomatous lesions of the iris. Correspondence: Hind Manaa Alkatan, Ophthalmology Keywords: amelanotic melanoma, clinicopathologic, ectropion uvea, neovascularization Department, College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, Tel +966 504492399, Fax +966112052740, Email Received: October 22, 2015 | Published: October 30, 2015 Abbreviations: KP’S, keratic precipitates; UBM, ultrasound infero-nasally, extending from 3 to 6 o’clock, involving the pupillary biomicroscopy; OCT, optical coherence tomography margin and causing ectropion uvea. -

Iris Cysts: Clinical Features, Imaging Findings, and Treatment Results

DOI: 10.4274/tjo.galenos.2019.20633 Turk J Ophthalmol 2020;50:31-36 Ori gi nal Ar tic le Iris Cysts: Clinical Features, Imaging Findings, and Treatment Results Helin Ceren Köse, Kaan Gündüz, Melek Banu Hoşal Ankara University Faculty of Medicine, Department of Ophthalmology, Ankara, Türkiye Abstract Objectives: To report the clinical and demographic characteristics, imaging findings, treatment results, and follow-up data of patients with iris cysts. Materials and Methods: The medical records of 37 patients with iris cysts were retrospectively analyzed. Ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM), swept-source optical coherence tomography (SS-OCT), and SS-OCT angiography (SS-OCTA) were performed to examine the iris cysts. Results: The mean age of the patients was 34.4 years, ranging from 5 to 85 years. Twenty-four patients (65%) were female and 13 (35%) were male. Mean follow-up period was 21.3 months, ranging from 4 months to 8 years. Thirty-five (94.5%) of the cysts were classified as primary and 2 (4.5%) were classified as secondary. Thirty-one (83.7%) of the primary cysts were pigment epithelial and 4 were stromal. Primary iris pigment epithelial (IPE) cysts were classified as peripheral in 26 patients (72.2%), midzonal in 4 (11.1%), and dislodged in 1 (2.7%). Stromal cysts were classified as acquired in 3 patients (8.1%) and congenital in 1 patient (2.7%). Secondary iris cysts were caused by perforating eye injury. UBM could visualize both the anterior and posterior surfaces of the cysts (26 patients). Anterior segment SS-OCT could visualize the anterior but not the posterior surface of the cysts (4 patients). -

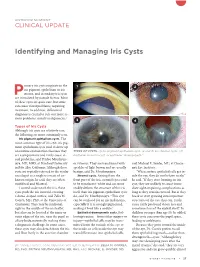

Identifying and Managing Iris Cysts

ANTERIOR SEGMENT CLINICAL UPDATE Identifying and Managing Iris Cysts rimary iris cysts originate in the 1 2 iris pigment epithelium or iris Pstroma, and secondary iris cysts are stimulated by outside factors. Most of these cysts are quite rare, but some can cause visual problems, requiring treatment. In addition, differential diagnosis is crucial to rule out more se rious problems, mainly malignancies.1 3 4 Types of Iris Cysts Although iris cysts are relatively rare, the following are more commonly seen. Iris pigment epithelium cysts. The most common type of iris cyst, iris pig ment epithelium cysts tend to show up on routine examinations because they TYPES OF CYSTS. (1) Iris pigment epithelium cyst. (2 and 3) Iris stromal cysts. (4) are asymptomatic and rarely cause vi Epithelial inclusion cyst, or epithelial “downgrowth.” sual problems, said Prithvi Mruthyun jaya, MD, MHS, at Stanford University or vitreous. They are translucent with said Michael E. Snyder, MD, at Cincin in Palo Alto, California. Although these speckles of light brown and are usually nati Eye Institute. cysts are typically referred to the ocular benign, said Dr. Mruthyunjaya. “When surface epithelial cells get in oncologist as a single iris mass of un Stromal cysts. Arising from the side the eye, they do not behave nicely,” known origin, he said, they are often front part of the iris, stromal cysts tend he said. “If they start forming an iris multifocal and bilateral. to be translucentwhite and can more cyst, they are unlikely to cause imme Located underneath the iris, these readily deform the struc ture of the iris diate sightimpairing complications as cysts push the iris forward, creating itself than iris pigment epithelium cysts long as they remain encased. -

Recurring Iris Pigment Epithelial Cyst Induced by Topical Prostaglandin

Correspondence: Dr Morini, Pediatric Ophthalmology Ser- Owing to planned cataract surgery of the right eye, bima- vice, Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù, Piazza S. Ono- toprost treatment was discontinued; periodic slitlamp ex- frio 4, 00165 Rome, Italy ([email protected]). aminations showed that the cyst gradually diminished and Financial Disclosure: None reported. finally disappeared within the following 6 weeks. Despite normal configuration of the anterior chamber and iris sur- 1. Gomes JA, Romano A, Santos MS, Dua HS. Amniotic membrane use in oph- thalmology. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2005;16(4):233-240. face, repeated ultrasound biomicroscopy revealed a small 2. Pires RT, Tseng SC, Prabhasawat P, et al. Amniotic membrane transplanta- cystic structure persisting close to the junction between the tion for symptomatic bullous keratopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117(10): 1291-1297. iris and ciliary body (Figure 2B). 3. Paridaens D, Beekhuis H, van Den Bosh W, Remeyer L, Melles G. Amniotic membrane transplantation in the management of conjunctival malignant mela- Comment. Both latanoprost and bimatoprost are topi- noma and primary acquired melanosis with atypia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001; 85(6):658-661. cally applied prostaglandin F2␣ analogues that lower in- 4. Goyal R, Jones SM, Espinosa M, Green V, Nischal KK. Amniotic membrane traocular pressure by improving uveoscleral outflow. In transplantation in children with symblepharon and massive pannus. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124(10):1435-1440. the reported case, the capability of latanoprost to induce 5. Lee SH, Tseng SC. Amniotic membrane transplantation for persistent epithe- iris cysts is confirmed by the recurrence of the cyst after lial defects with ulceration. -

Clinical Features of Iris Cysts in Long-Term Follow-Up

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Clinical Features of Iris Cysts in Long-Term Follow-Up Joanna Konopi ´nska*, Łukasz Lisowski, Zofia Mariak and Iwona Obuchowska Department of Ophthalmology, Medical University of Białystok, Jana Kili´nskiego1 STR, 15-089 Białystok, Poland; [email protected] (Ł.L.); [email protected] (Z.M.); [email protected] (I.O.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-8-5746-8372 or +48-6-0047-1666 Abstract: This study evaluated the characteristics and clinical course of patients with iris cysts in the long-term follow-up (24–48 months). We retrospectively analyzed the medical records of 39 patients with iris cysts (27 women and 12 men). Age, visual acuity, intraocular pressure (IOP), slit-lamp evaluation, and ultrasound biomicroscopy images were assessed. The mean age at diagnosis was 40.6 ± 17.48 years. Thirty (76.9%) cysts were peripheral, five (12.8%) were located at the pupillary margin, two (5.1%) were midzonal, and two (5.1%) were multichamber cysts extending from the periphery to the pupillary margin. A total of 23 (59%) cysts were in the lower temporal quadrant, 11 (28.2%) were in the lower nasal quadrant, and 5 (12.8%) were in the upper nasal quadrant. Cyst size was positively correlated with patient age (rs = 0.38, p = 0.003) and negatively correlated with visual acuity (rs = −0.42, p = 0.014). Cyst growth was not observed. The only complication was an increase in IOP in three (7.7%) patients with multiple cysts. The anatomical location of the cysts cannot differentiate them from solid tumors. -

Uveal Melanoma: S Kaliki and CL Shields REVIEW Relatively Rare but Deadly Cancer

Eye (2017) 31, 241–257 © 2017 Macmillan Publishers Limited, part of Springer Nature. All rights reserved 0950-222X/17 www.nature.com/eye 1 2 Uveal melanoma: S Kaliki and CL Shields REVIEW relatively rare but deadly cancer Abstract Although it is a relatively rare disease, primarily locations, including skin, mucous membrane foundintheCaucasianpopulation,uvealmela- (nasal mucosa, oropharyngeal, pulmonary, noma is the most common primary intraocular gastrointestinal, vaginal, anal/rectal, urinary tumor in adults with a mean age-adjusted tract), ocular region (uvea, conjunctiva, eyelid, incidence of 5.1 cases per million per year. orbit), and rarely from unknown primary sites.1 Tumors are located either in iris (4%), ciliary In a review of 84 836 cases from the National body (6%), or choroid (90%). The host suscept- Cancer Database, including cases diagnosed ibility factors for uveal melanoma include fair between 1985 and 1994, the percentages of skin, light eye color, inability to tan, ocular or melanomas arising from the skin, eye and oculodermal melanocytosis, cutaneous or iris or adnexa, mucosa, and unknown primaries were choroidal nevus, and BRCA1-associated protein 91%, 5%, 1%, and 2%, respectively.1 1 mutation. Currently, the most widely used first- Among ocular melanomas, 83% arise from line treatment options for this malignancy are uvea, 5% from conjunctiva, and 10% from other resection, radiation therapy, and enucleation. sites.1 The most common site for uveal There are two main types of radiation therapy: melanoma is the choroid. In a study of 8033 plaque brachytherapy (iodine-125, ruthenium- patients with uveal melanoma by Shields et al,2 106, or palladium-103, or cobalt-60) and telether- the tumor was located in the iris in 285 (4%), apy (proton beam, helium ion, or stereotactic ciliary body in 492 (6%), and choroid in 7256 radiosurgery using cyber knife, gamma knife, or (90%) cases. -

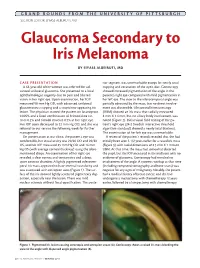

Glaucoma Secondary to Iris Melanoma

GRAND ROUNDS FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SECTION EDITOR: EIYASS ALBEIRUTI, MD Glaucoma Secondary to Iris Melanoma BY EIYASS ALBEIRUTI, MD CASE PRESENTATION rior segment was unremarkable except for nearly total A 63-year-old white woman was referred for ad- cupping and excavation of the optic disc. Gonioscopy vanced unilateral glaucoma. She presented to a local showed increased pigmentation of the angle in the ophthalmologist urgently due to pain and blurred patient’s right eye compared with mild pigmentation in vision in her right eye. Upon examination, her IOP her left eye. The view to the inferotemporal angle was measured 58 mm Hg OD, with advanced unilateral partially obscured by the mass, but no direct involve- glaucomatous cupping and a suspicious-appearing iris ment was discernible. Ultrasound biomicroscopy lesion. The physician started the patient on latanoprost (UBM) showed an iris mass that radially measured 0.005% and a fixed combination of brimonidine tar- 3 mm X 1.4 mm, but no ciliary body involvement was trate 0.2% and timolol maleate 0.5% in her right eye. noted (Figure 2). Initial visual field testing of the pa- Her IOP soon decreased to 22 mm Hg OD, and she was tient’s right eye (24-2 Swedish interactive threshold referred to our service the following week for further algorithm-standard) showed a nearly total blackout. management. The examination of her left eye was unremarkable. On presentation at our clinic, the patient’s eye was A review of the patient’s records revealed that she had comfortable, her visual acuity was 20/40 OD and 20/30 initially been seen 5 1/2 years earlier for a raised iris mass OS, and her IOP measured 25 mm Hg OD and 14 mm (Figure 3), with radial dimensions of 2.5 mm X 1 mm on Hg OS (with average corneal thickness) using the afore- UBM. -

Plateau Iris

26 Plateau Iris Yoshiaki Kiuchi, Hideki Mochizuki and Kiyoshi Kusanagi Hiroshima University Japan 1. Introduction Primary angle-closure glaucoma (PACG) is a common form of glaucoma in Asia (Foster & Johnson, 2001). It is associated with a high risk of visual loss (Congdon et al., 1992; Foster et al., 1996). PACG was estimated to blind 5 times more people than primary open-angle glaucoma (Quigley et al. 2001). The original concept of primary angle closure glaucoma was a pupil- block angle-closure mechanism occurring in predisposed eyes with shallow anterior chamber angles. Peripheral iridectomy prevents the progression of primary angle closure glaucoma (Lowe, 1964). However, many patients experienced recurrent angle-closure glaucoma attacks after iridectomy (Wand et al., 1977). The occurrence of narrow angle in eyes with relatively normal depth in the anterior chamber and a relatively flat iris plane had been noted as early as 1940 (Gradle & Sugar, 1940). Chandler presented the case of a patient with repeated intermittent angle-closure glaucoma attacks despite a patent iridectomy, who was successfully treated with pilocarpine (Wand et al., 1977). Those cases were considered to be different from ordinary cases of narrow angle glaucoma. They were particularly found Fig. 1. Plateau iris configuration. Ultrasound biomicroscopy image shows a flat iris plane ( ) accompanied by a narrow or closed anterior chamber angle. Plateau iris configuration is caused by anteriorly located ciliary processes ( ), which close the ciliary sulcus and provide support to the peripheral iris www.intechopen.com 524 Glaucoma - Basic and Clinical Concepts in younger patients in whom a peripheral iridectomy is often ineffective. These patients had a flat iris and a narrow angle secondary to an abrupt angulation at the root of the iris.