Canberra 11 Canberra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Canberra Tour

2012 Canberra Tour 149 students are going on camp. The Teachers attending the Camp are: Jamie Peters, Melissa Bull, Natasha Richardson, Simon Radford, Melissa Brown, Crissy Samaras, Sarah Nobbs and Felicity Minton. Vicki Symons and Malinda Vaughn(Fri) will be at school to run the „At School Program‟. Off to Canberra –Get to school on time The departure date for the camp is Monday 30th of April (Week 3 of Term 2). Students are expected to be at school no later than 7:15am as the bus is leaving at 7.30. Make sure you get signed off when you arrive –there will be signs for you to know where you have to line up. If your child has any medication they must be at school between 7:00-7:15am to hand in their medication to Sarah Nobbs in the Gym foyer. We catch the bus back to school on Friday 4th May returning at approximately 5:30pm. WHY GO TO CANBERRA ? It is part of the school‟s camp policy, that this Educational Tour of Canberra is ran every second year to empower our students to become better citizens with valuable knowledge in Civics and Citizenship, Australian History and the Australian Government. What happens during the day on Camp? Each day the students will be touring the sights of Canberra. The tour destinations shown later in this presentation will be conducted by professional guides. The tours are aimed at the interest of grade 5/6 students and are interactive where appropriate. Some of the Evening Activities may include: – A Movie night – A Night Tour – Mount Ainslie – Common Room Free Activities – A Disco/Quiet games - A Trivia Night Day 1 Itinerary Monday, 30th April 2012 7.00am - Coaches arrive at Williamstown North Primary School to load luggage. -

NATIONAL TRUST of AUSTRALIA Heritage in Trust (ACT) March 2019 ISSN 2206-4958

NATIONAL TRUST OF AUSTRALIA Heritage in Trust (ACT) March ISSN 2206-4958 2019 North-western corner of School House, showing old fireplace and part of original building that Ainslie and his men would have lived in until the rest of the hut was completed The early history of St John’s School House Contents There is some controversy about the age and the use of The early history of St John’s School House by St John’s School House. Robert Campbell p1-3 What really happened when James Ainslie came to the ACT Trust News p3-5 Limestone Plains in 1824? Where did he and his What’s next - coming up p5-6 shepherds live? Little is known about shepherds, their Heritage Festival p6-7 sheep and the huts they lived in on the Limestone Heritage Diary p8-9 Plains, in those early days. Where did Ainslie and his Tours and events – what’s been happening p9-12 shepherds live if not in the hut which later became the Heritage Symposium p12-13 School House? C S Daley Desk and Chair p13-14 The Duntroon House area would have been unsuitable Heritage Happenings p14 because it was too far from the sheep-grazing area. Letters p15-16 On the other hand, the hut was built in an area of 4,000 Donation Form p16 acres carrying 3,000 to 4,000 sheep with six or seven shepherds. Heritage in Trust www.nationaltrust.org.au Page 1 Heritage In Trust March 2019 Unfortunately, Campbell documents that could provide view of the church burial ground immediately evidence are gone. -

The Secret Life of Elsie Curtin

Curtin University The secret life of Elsie Curtin Public Lecture presented by JCPML Visiting Scholar Associate Professor Bobbie Oliver on 17 October 2012. Vice Chancellor, distinguished guests, members of the Curtin family, colleagues, friends. It is a great honour to give the John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library’s lecture as their 2012 Visiting Scholar. I thank Lesley Wallace, Deanne Barrett and all the staff of the John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library, firstly for their invitation to me last year to be the 2012 Visiting Scholar, and for their willing and courteous assistance throughout this year as I researched Elsie Curtin’s life. You will soon be able to see the full results on the web site. I dedicate this lecture to the late Professor Tom Stannage, a fine historian, who sadly and most unexpectedly passed away on 4 October. Many of you knew Tom as Executive Dean of Humanities from 1999 to 2005, but some years prior to that, he was my colleague, mentor, friend and Ph.D. supervisor in the History Department at UWA. Working with Tom inspired an enthusiasm for Australian history that I had not previously known, and through him, I discovered John Curtin – and then Elsie Curtin, whose story is the subject of my lecture today. Elsie Needham was born at Ballarat, Victoria, on 4 October 1890 – the third child of Abraham Needham, a sign writer and painter, and his wife, Annie. She had two older brothers, William and Leslie. From 1898 until 1908, Elsie lived with her family in Cape Town, South Africa, where her father had established the signwriting firm of Needham and Bennett. -

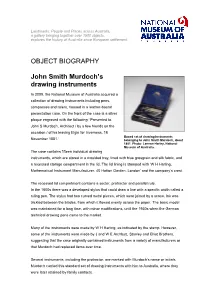

OBJECT BIOGRAPHY John Smith Murdoch's Drawing Instruments

Landmarks: People and Places across Australia, a gallery bringing together over 1500 objects, explores the history of Australia since European settlement. OBJECT BIOGRAPHY John Smith Murdoch’s drawing instruments In 2009, the National Museum of Australia acquired a collection of drawing instruments including pens, compasses and rulers, housed in a leather-bound presentation case. On the front of the case is a silver plaque engraved with the following: ‘Presented to John S Murdoch, Architect / by a few friends on the occasion / of his leaving Elgin for Inverness. 18 Boxed set of drawing instruments November 1881.’ belonging to John Smith Murdoch, about 1881. Photo: Lannon Harley, National Museum of Australia. The case contains fifteen individual drawing instruments, which are stored in a moulded tray, lined with blue grosgrain and silk fabric, and a recessed storage compartment in the lid. The lid lining is stamped with ‘W H Harling, Mathematical Instrument Manufacturer, 40 Hatton Garden, London’ and the company’s crest. The recessed lid compartment contains a sector, protractor and parallel rule. In the 1600s there was a developed stylus that could draw a line with a specific width called a ruling pen. The stylus had two curved metal pieces, which were joined by a screw. Ink was trickled between the blades, from which it flowed evenly across the paper. The basic model was maintained for a long time, with minor modifications, until the 1930s when the German technical drawing pens came to the market. Many of the instruments were made by W H Harling, as indicated by the stamp. However, some of the instruments were made by J and W E Archbutt, Stanley and Elliot Brothers, suggesting that the case originally contained instruments from a variety of manufacturers or that Murdoch had replaced items over time. -

Luxury Lodges of Australia Brochure

A COLLECTION OF INDEPENDENT LUXURY LODGES AND CAMPS OFFERING UNFORGETTABLE EXPERIENCES IN AUSTRALIA’S MOST INSPIRING AND EXTRAORDINARY LOCATIONS luxurylodgesofaustralia.com.au LuxuryLodgesOfAustralia luxurylodgesofaustralia luxelodgesofoz luxelodgesofoz #luxurylodgesofaustralia 2 Darwin ✈ 19 8 4 6 8 10 15 ARKABA BAMURRU PLAINS5 Kununurra ✈ CAPELLA LODGE 10 CAPE LODGE Ikara-Flinders Ranges, South Australia Top End, Northern Territory Lord Howe Island, New South Wales ✈ CairnsMargaret River, Western Australia Broome ✈ 12 NORTHERN ✈ Hamilton Island TERRITORY 14 Exmouth ✈ 12 14 ✈ Alice Springs 16 QUEENSLAND 18 EL QUESTRO HOMESTEAD EMIRATES ✈ONE&ONLY Ayers Rock (Ulu ru) 9 LAKE HOUSE LIZARD ISLAND The Kimberley, Western Australia WESTERNWOLGAN VALLEY Daylesford, Victoria Great Barrier Reef, Queensland Luxury Lodges of Australia AUSTRALIABlue Mountains, New South Wales 17 A collection of independent luxury lodges and camps offering Brisbane ✈ unforgettable experiences in Australia’s most inspiring and SOUTH extraordinary locations. AUSTRALIA Australia’s luxury lodge destinations are exclusive by virtue of their 1 Perth ✈ 3 access to unique locations, people and experiences, and the small NEW SOUTH 20 22 24 26 number of guests they accommodate at any one time. Australia’s sun, WALES 6 11 Lord Howe Island ✈ LONGITUDE 131°4 MT MULLIGAN LODGE PRETTY BEACH HOUSE QUALIA sand, diverse landscapes and wide open spaces are luxuries of an 18 ✈ Ayers Rock (Uluru), Northern Territory Northern Outback, Queensland Sydney Surrounds, New South Wales GreatSydney -

TFE Hotels and Velocity Frequent Flyer – Terms & Conditions Brands

TFE Hotels and Velocity Frequent Flyer – Terms & Conditions A By Adina in Australia Adina Apartment Hotels in Australia and New Zealand Adina Serviced Apartments in Australia and New Zealand Rendezvous Hotels in Australia and New Zealand Brands involved Travelodge Hotels in Australia and New Zealand Vibe Hotels in Australia Hotel Kurrajong Canberra Hotel Britomart Auckland The Calile Hotel Brisbane The Savoy Hotel on Little Collins Melbourne Quincy Hotel Melbourne 2 – Travelodge Hotels Points earned per $ spent (by 3 – A by Adina, Adina, Vibe, Rendezvous, Hotel Kurrajong Canberra, brand) Hotel Britomart Auckland, The Calile Hotel Brisbane, The Savoy Hotel on Little Collins Melbourne, Quincy Hotel Melbourne Accommodation rate only Applicable spend areas • Points can be earned for a maximum of 7 nights only • Guest is not allowed to make consecutive bookings and check in and check out to get points • Points cannot be split between two or more members occupying Maximum Stay the room • Points will only be issued to the person whose name is on the invoice for the hotel stay • Points are not awarded to No Shows • Maximum of 3 rooms paid per member card for any common stay period Rate thresholds apply at each hotel, please check with the hotel . Standard is anything below 50% of rack rate. The upon booking following rate types are also excluded: • Package Stays • Free Hotel Stays • Industry Rate discounts • Group or Conference rates • Award certificates or discount certificates • Wholesaler and Inbound rates • Tour Series rates Excluded rate -

Prime Minister's Lodge

Register of Significant Twentieth Century Architecture RSTCA No: R006 Name of Place: The Lodge Other/Former Names: Address/Location: Adelaide Avenue and National Circuit DEAKIN 2600 Block 1 Section 3 of Deakin Listing Status: Registered Other Heritage Listings: RNE Date of Listing: 1984 Level of Significance: National Citation Revision No: Category: Residential Citation Revision Date: Style: Inter-War Georgian Revival Date of Design: 1926 Designer: Oakley & Parkes Construction Period: 1926-27 Client/Owner/Lessee: C of A Date of Additions: 1952-78 Builder: James G Taylor Statement of Significance The Lodge is important as the only purpose built official residence constructed for the Prime Minister or Governor-General and otherwise one of only four of their official residences in Australia. It is of historical significance as the official residence of almost all Prime Ministers since its completion in 1927. The Lodge is also associated with the development of Canberra as the national capital, especially the phase which saw the relocation of Parliament to the new city. The Lodge provides a suite of reception rooms in a building and setting of appropriately refined and dignified design, which demonstrates the principal characteristics of an official residence suitable for the incumbent of that office. The building is a fine example of the Inter-War Georgian Revival style of architecture, with features specific to that style, such as symmetrical prismatic massing and refined Georgian detailing. It is also significant for its associations with the architects Oakley and Parkes, who played a key role in the design of Canberra's permanent housing in its initial phase. -

A National Cultural Pride

+#DELVEINTO AUSTRALIA A NATIONAL CULTURAL PRIDE Canberra proved to 20 buyers that they are ready for interstate and international business events. WORDS: EL KWANG PHOTOGRAPHY: CHUA YI KIAT National Convention Centre Park Hyatt Canberra The Canberra Convention Bureau LUNCHEONS THAT TOLD A (CCB) and participating members were STORY ready to showcase all things fabulous It was a clever way to immerse guests in the capital of Australia to some 20 into a destination by having Historian buyers and Biz Events Asia with the David Headon share the rich history of destination’s Top Secret FAM tour in Canberra at the welcome luncheon in early March 2017. the rose courtyard of the Park Hyatt Canberra. The storytelling made an According to the CCB, Top Secret is a impact as the buyers were paying key initiative that has a strong track attention to the value of history and record of bringing in tens of millions national cultural institutions Canberra of dollars in meeting and convention offers throughout the trip. business for the city with over AUD88 million in economic contribution to The National Convention Centre in date. Michael Matthews, CEO of CCB Canberra truly wowed the buyers with said: “Top Secret showcases Canberra’s an unforgettable experience. The team energetic and creative business events set up the entire exhibition hall with community that stands ready to deliver exhibition booths so buyers can see the world-class business events. Decision possibilities of the revenue generating makers see firsthand just how great exhibition as part of the conferences. their business event in Canberra From there, the buyers were led into will be.” the Royal Theatre where Stephen Wood, General Manager of the Centre, Here are some of the key highlights kicked off an impressive long table from the three-day experience selected gastronomy experience on the stage. -

So You Want to Be Prime Minister? It Doesn’T Matter If You’Re Rich Or Poor, a Snappy Dresser Or a Messy Eater

Walker Books Classroom Ideas Our Stories: *Notes may be downloaded and printed for regular classroom use only. So You Want To Be Ph +61 2 9517 9577 Walker Books Australia Fax +61 2 9517 9997 Prime Minister? Locked Bag 22 Author: Nicolas Brasch Newtown, N.S.W., 2042 Illustrator: David Rowe ISBN: 9781922179258 These notes were created by Steve Spargo. ARRP: $18.95 For enquiries please contact: [email protected] NZRRP: $21.99 September 2013 Notes © 2013 Walker Books Australia Pty. Ltd. All Rights Reserved Outline: So you want to be prime minister? It doesn’t matter if you’re rich or poor, a snappy dresser or a messy eater. Australia’s prime ministers have had very different backgrounds – Paul Keating managed a rock band and Chris Watson swept up horse manure. You have a better than average chance if your first name is John and you were born in Victoria. Read this handbook of helpful hints and you could be the next prime minister. Author/Illustrator Information: Nicolas Brasch is the author of more than 350 books for children and young adults. His books have been sold in every major English-speaking market including Australia, USA, UK, Canada, South Africa, Zimbabwe and New Zealand, as well as several non-English speaking markets including South Korea, Germany and Turkey. David Rowe is an award-winning political cartoonist. How to use these notes: This story works on many levels. The suggested activities are therefore for a wide age and ability range. Please select accordingly. These notes Key Learning Example of: Themes/ National Curriculum Focus:* are for: Areas: • Non-fiction Ideas: English content descriptions: • Primary • English • Australian English History Year 6 *Key content years 5 & 6 • History Year 5 Year 6 Year 5 ACHHS104 descriptions have history ACELA1504 ACELA1518 ACHHS098 ACHHK116 been identified ACELA1797 ACELA1524 ACHHS100 ACHHS117 from the Australian • Ages 10+ • Australian National Curriculum. -

Walk to the Animals

THE WEEKEND AUSTRALIAN, FEBRUARY 11-12, 2012 www.theaustralian.com.au TRAVEL & INDULGENCE 3 { DESTINATION AUSTRALIA } Masterpieces and makeovers Walk to the animals in the national capital with a plump mattress topper, A heritage hotel in downtown Canberra duvet and crisp linen providing is having its own grand renaissance an ideal haven after a soothing soak in the newly installed tub. Elementsofthehotel’sjazzage SHARON FOWLER history can be found at intervals around the property. The small drive from the NGA, is still wood-panelled reception lounge Olims, the name it has carried evokes a glimpse of days gone by STATE since 1989. Yet that is just one of with high-backed armchairs, OF PLAY the hotel’s many guises. It first high brick fireplace and a glass opened in 1927 as the Ainslie, its divider panel featuring an construction coinciding with the etched lyrebird, the hotel’s completion of Parliament House. original symbol. I AM standing before a Madonna Walter Burley Griffin, Can- The upstairs corridors are and Child canvas, its paint deftly berra’s designer, and his wife, whitewashed, light and airy, with applied more than half a millen- Marion Mahony Griffin, were framed photographs illustrating nium ago by Venetian artist just two of the hotel’s esteemed the property’s history. Wood- Carlo Crivelli. Mary is draped in original guests. It was also known framed panelled windows in scarlet and an intricately pat- for many years as Spendloves many guestrooms overlook the terned gold mantle as she cradles Hotel (after the then owners) and central paved courtyard edged baby Jesus. -

Conference, Meetings & Events

Conference, Meetings & Events Kit 2 | Hotel Kurrajong Canberra Welcome Hotel Kurrajong Canberra combines contemporary style and luxury with Art Deco elegance. It is the ideal location for your next meeting, conference or event. Built in 1926, it offers a one-of-a-kind experience with warm hospitality and a taste of the Capital’s early history. The pavilion-style buildings with pretty terrace gardens comprise 147 rooms and include four executive suites, four balcony rooms and eight terrace rooms. With five unique meeting spaces, as well as an exclusive private dining room, Hotel Kurrajong Canberra can cater for a small board meeting of eight through to cocktail parties of up to 200 guests. Chifley’s Bar & Grill is named after the 16th Prime Minister of Australia, Ben Chifley, who loved dining here and frequently enjoyed a tipple in the bar. We pay homage to the region’s wineries and boutique food producers with a seasonal, modern menu. A wide range of local and international wines, cocktails, craft beers and ciders are available for your drinking pleasure. We pride ourselves on our professional and personalised service. Let our event specialists create an event or occasion to remember. Welcome to Hotel Kurrajong Canberra, Where the Capital Lives Hotel Kurrajong Canberra | 3 4 | Hotel Kurrajong Canberra The Location Hotel Kurrajong Canberra is conveniently located within a short distance of both the parliamentary precinct and central business district, making access easy for everyone. Events with Benefits Book your next event with TFE Hotels and enjoy a host of reward options for both the company and for the booker. -

Lloa Brochure Trade.Pdf

The new era of Australian experiential luxury… There’s nothing like In recent years, the Australian travel landscape has changed. We have seen Australia for its sheer the emergence and consolidation of a new breed of exceptional luxury lodges, diversity of natural camps and experiences. These independent properties have luxury experiences... joined forces to showcase diverse and In recent years, Australia has seen the development of a new breed authentically Australian experiences and of exceptional luxury properties and experiences, changing the unique style of sophisticated, carefree, Australian travel landscape significantly. barefoot luxury. In 2010 the best of these properties joined forces and formed Luxury Lodges of Australia, to showcase Australia’s unique style of sophisticated, carefree, barefoot luxury. Who are they? The common theme defining the lodges is the authentic sense Page of place and the unique experience each lodge offers guests – experiences that really connect their guests to the region in which A COLLECTION OF INDEPENDENT LUXURY LODGES AND CAMPS 2 Arkaba they are located. OFFERING UNFORGETTABLE EXPERIENCES IN AUSTRALIA’S 3 Bamurru Plains All offer the key luxury standards expected by upscale travellers – MOST INSPIRING AND EXTRAORDINARY LOCATIONS 4 Capella Lodge outstanding food and wine, high levels of personal service, extremely high quality amenities – but each lodge interprets those standards in 5 Cape Lodge their own style, and appropriate to their region. 6 Crystalbrook Lodge It is not about how similar