1 HARTFORD CIRCUS FIRE Samuel Strader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Man Who Walks on Air Last Year He Became the First Person in History to Walk a Tightrope Directly Over Niagara Falls

Nik Wallenda—Scion of the Wallenda Dynasty of Daredevils The Man Who Walks On Air Last year he became the first person in history to walk a tightrope directly over Niagara Falls. A few weeks ago he became the first man to grace a highwire above the dizzying drop of the Grand Canyon. Now he is planning to walk from the Empire State Building to the Chrysler Building, covering nine city blocks high above the busy streets of Manhattan. Nik Wallenda has made himself famous as funambulist par excellence with his tightrope walks over the most frightening spots around the world. He knows that some of his predecessors were killed in the attempt, yet he is convinced that he is destined to die a natural death. - Aviva Sternfeld 30 | ZMAN • September 2013 ZMAN • Elul 5773 | 31 aredevils may be motivated by fame courage” in the early 1920s, Karl Wallenda or money. Some are drawn to the quickly applied for the job. Dthrill of taking on a dangerous chal- The job involved performing together lenge. Nik Wallenda argues that he belongs with another stuntman named Louis to none of those categories. He dislikes the Weitzman. As Weitzman’s assistant, he term “daredevil” altogether. Wallenda points was to follow Weitzman on a tightrope and out that he invests tremendous effort before do a handstand on Weitzman’s hands in Karl Wallenda, patriarch of the Flying Wallendas, at work above London. each performance to ensure that he is not the middle of the tightrope. Working with risking his life. He trains continuously and Weitzman, Karl Wallenda perfected the art tests all of his equipment faithfully. -

Radio City Christmas Spectacular

Broadway Buzz- Radio City Christmas Spectacular It’s Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas THE RADIO CITY CHRISTMAS Talking with the SPECTACULAR returns to Rockettes PlayhouseSquare for the most -Read More- wonderful time of the year. This beloved holiday extravaganza will kick up its heels December 4-28, 2008 as part of the KeyBank Broadway Series. Costumes by Starring the world famous Radio City Numbers Rockettes, dancing teddy bears, -Read More- wooden soldiers, live camels, a living nativity, and Santa Claus, it is no wonder that Time Magazine says the show “lifts the spirit” and the Boston Herald declares it “a rare Enrich Your gem!” Experience -Read More- Photo: The Rockettes - MSG Entertainment Read More.... http://www.playhousesquare.org/bbuzz/radiocity/ (1 of 2) [1/9/2009 2:25:50 PM] Broadway Buzz- Radio City Christmas Spectacular Which upcoming Buzz Extra is a publication of the Arts KeyBank Broadway Education Department at PlayhouseSquare Series show are you most Vice President of Theatricals: looking forward to seeing? Gina Vernaci Radio City Christmas Director of Arts Education: Spectacular Colleen Porter Spring Awakening Director of Ticket Sales & Marketing: Mary Poppins Autumn Kiser Editors: Linda Jackson, Cindi Szymanski Writer: Watch a Video Robin Pease Official Website Photos: Download Radio City's New Christmas Favorites MSG Entertainment and Janet Macoska CD Download and read the printable version of the Buzz (535Kb in Home PDF format) here. It's Beginning to Look A Lot Like Christmas Legally Blonde Talking with the Rockettes A Chorus Line Costumes by the Numbers Origins of the Rockettes We welcome your feedback and suggestions for the Buzz Extra. -

A Vipul M Desai's Presentaion

WALK ACROSS NIAGRA – નાયગ્રાની પેલે પાર દોરડાપર A VIPUL M DESAI’S PRESENTAION FOR MORE CLICK FOLLOWING LINK http://suratiundhiyu.wordpress.com/ [email protected] નાયગ્રા ધોધ પર દોરડા પર ચાલીને જનાર પ્રથમ માણસ – નીક વોલẂડા Feat: Nik Wallenda walks across the Niagara Falls in an attempt to be the first man ever to complete the walk નાયગ્રા ધોધના ઝંઝાવતી તોફાનમાં ઘણા લોકોએ 犾ન ગમુ ા훍યા તયાં વોલẂડા અડગ ઉભાછે Danger: Mr Wallenda was finely poised above the surging waterfall which has taken many casualties in the past Relief: The daredevil punched the air when he made it to the other side after 25 minutes Epic: Mr Wallenda described the view over the Falls, which he is the only person ever to have seen, as 'breathtaking' Torrents: The skilled tightrope walker never broke his concentration, even when surrounded by the rush of thousands of gallons of water Spray: The water coming off the Falls was just one of several weather phenomena which Mr Wallenda had to contend with નાયગ્રાના ધોધના પ્રચંડ ધોધ સામે વોલẂડા ખબુ જ નાના દેખાય છે Scale: From afar, the walker is barely visible against the background of the mighty Niagara Falls Breathtaking: The spectacle enjoyed by Mr Wallenda during his unique experience is unlike that granted to anyone else Setting out: Mr Wallenda pictured just a couple of minutes after starting his walk, when he was still walking downhill into the 'valley' of the rope Afterwards, he said he accomplished the feat through 'a lot of praying, that's for sure. -

WHY PAY but Only a Trickle of Results Were in Were Overwhelmingly Rejecting the Was Rejected by the Union Bargaining Balloting

PAGE TEN-A - MANCHESTER EVENING HERALD, Mancfaerier, Conn.. Thuri.. March 23. \ m Family keeps working OUtuariM M ideast (Continned from Page One) The weather Mrs. Laurel K. Nelson Kazimierz Kielian Two hundred and fifty Swedish of Clear and cold^ tonight with lows in ^ ELLINGTON — Kazimierz ficers were assigned the the 20s. Fair and cool Saturday with Mn. Laurel Kemmerer Nelson, 79, highs in the 40s. National weather after Wallenda’s death of 333 Bidwell St. died IlMsday at a Kielian, W, formerly of Abbot Road, northeastern sector in the area of the map on page 6B. Mancbeater convalescent home. died Wednesday at a Vernon area Christian town of Marjayoun, while Manchester—A City of Village Charm Phone 647-9946 Mrs. Nelson was bom in Hartford convalescent lume. 200 Iranians were scfaedoled to patrol TWENTY PACES SAN JUAN, Puerto Rico (UPl) - balancing bar until his skull hit the Circus only hours after watching her and bad lived in Elmwood for more Mr. Kielian was bora Feb. 7,1891, the central sector. i TWO SECTIONS MANCHESTER. CONN., FRIDAY. MARCH 24, 1978 - VOL. XCVII. No, 147 for home delivery After so years of death-defying acts back of a parked taxi. grandfather die. than 40 years before coming to in Poland and bad lived in Ellington The U.N. troops will be stationed I I'RICE: TWENTY CKN'TS on the tightrope, 73-year-oId Karl He was dead on arrival at nearby In Concord, Calif., Steve Wallenda, Manchester two years ago. St« was a for more than 50 years. He bad betwen the Istmli lines and the A Wallenda is dead. -

The Balancing Act Is Dedicated to Three Cousins: BJ Scarfone, Lynne Manilla, and Sandi Manilla, of Blessed Memory, for Helping Us Keep Our Balance!

The Balancing Act is dedicated to three cousins: BJ Scarfone, Lynne Manilla, and Sandi Manilla, of blessed memory, for helping us keep our balance! Welcome! Circus is about humans overcoming challenges. Our entire world is challenged right now. As a nonprofit social circus school, we feel like we are walking a tightrope. Under normal circumstances, we know how to walk a tightrope, however the length keeps getting extended. When you are learning to walk a tightrope, if you start to lose your balance, you don’t stay in one place and fight to get it back. The best thing to do to regain your balance is to take your next step forward. One of our students, Will Hickey, said, “It’s important to look for balance. It doesn’t necessarily seek you out if you don’t look for it.” From their living rooms, bedrooms, backyards, and local parks, Circus Harmony students and alumni have created new acts and tell the stories of how they are keeping their balance in this unbalanced time. Will observed, “This show feels like it’s taking our separated lives and individual experiences and attaching them. There’s a reason people make quilts and not just regular blankets.” Come wrap yourself in this show, like the circus itself, the show is daring and funny, exciting and entertaining, heart-stopping and heart-warming. I think you will be inspired by these young people’s strength, grace, and resilience. Jessica Hentoff Pre-Show A view into how some of Circus Harmony’s alumni, students, parents and coaches are keeping their balance. -

To Download The

Your Community Voice for 50 Years RecorPONTE VEDRA der INSIDER’STournament Guide RORY LOOKING STILL BACK 20 years ago, REIGNS Tiger Woods made McIlroy remains defending champ after 2020 cancellation an astonishing putt on the No. 17 en route to the title, and other major milestones A NEW HOME PGA TOUR opens state-of-the-art global headquarters Pristine Waterfront Immaculately maintained home located on a cul de sac Atlantic Beach Retreat Ideally located in Atlantic Beach, this 3-story town- on the largest lake in Marsh Landing features a spacious floor plan, first floor home is only two blocks away fom the ocean as well as the Beaches Town master, and expansive 180-degree water views showcased throughout. Center. Enjoy the home’s rooftop deck or the easily maintained backyard 4 bedrooms, 4.5 baths oasis complete with a 6-ft. privacy fence, covered patio, and relaxing hot tub. 3 bedrooms, 2F/2H baths $810,000 “Model” Home in Alta Lakes Lightly lived-in and beautifully maintained, Oceanfront Beach Escape Located between The Lodge and the Cabana this house looks & feels like a model home with tall ceilings, a neutral Beach Club, this second-story condo gives elevated views of the beach while palette, and an open floor plan ideal for everyday life. Featuring water maintaining the unit’s privacy and security. Includes a large covered balcony to woods views along with smart home features & premium upgrades. and ground floor storage.3 bedrooms, 3 bathrooms $1,585,000 3 bedrooms, 2 baths $290,000 Sophisticated Coastal Luxury A masterpiece of design and craftsmanship, Pristine Craftsmanship on Ponte Vedra Blvd. -

The Legacy of John Ringling and the American Circus

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston Graduate Masters Theses Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses 5-2020 Beyond the Big Top: The Legacy of John Ringling and the American Circus Casey L. Nemec Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umb.edu/masters_theses Part of the United States History Commons BEYOND THE BIG TOP: THE LEGACY OF JOHN RINGLING AND THE AMERICAN CIRCUS A Thesis Presented By CASEY L. NEMEC Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2020 History Program © 2020 by Casey L. Nemec All rights reserved BEYOND THE BIG TOP: THE LEGACY OF JOHN RINGLING AND THE AMERICAN CIRCUS A Thesis Presented By CASEY L. NEMEC Approved as to style and content by: Vincent J. Cannato, Associate Professor Chairperson of Committee Timothy Hacsi, Associate Professor Member Roberta Wollons, Professor Member Elizabeth McCahill, Program Director History Program Timothy Hacsi, Chair History Department ABSTRACT BEYOND THE BIG TOP: THE LEGACY OF JOHN RINGLING AND THE AMERICAN CIRCUS MAY 2020 Casey L. Nemec, B.A., Florida Gulf Coast University M.A., University of Massachusetts Boston Directed by Professor Vincent J. Cannato Beyond the Big Top: The Legacy of John Ringling and the American Circus is a focused interpretation of the impact of the American circus post-Civil War through present day, most particularly that of circus impresario, corporate magnate, and philanthropist John Ringling, in what was once a quiet Florida fishing village named Sarasota. It is my observation that John Ringling, through moving the winter quarters of the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey to Sarasota, investing in a sizable amount of real estate, and spearheading a campaign to bring a world-class art museum and school to the area, played a key role in shaping Florida tourism, diversity, expanding cultural awareness, and boosting the local economy. -

Bibliography (PDF)

Ally and Jordi’s Adventures Through Florida Source Bibliography Intro Page Our State “Florida Facts.” Florida Department of State, http://dos.myflorida.com/florida-facts/. Mifflin, H. (2005). Social Studies Florida (Student Edition 4th Grade). Boston. Gannon, Michael. Florida: a Short History. University Press of Florida, 2003. Nature “Florida Quick Facts.” State of Florida.com, www.stateofflorida.com/facts.aspx. Industry “Facts About Florida Oranges & Citrus.” Visit Florida, www.visitflorida.com/en-us/eat- drink/facts-about-florida-citrus-oranges.html. History Viva Florida! 500 Years of La Florida, flawildflowers.org/vivaflorida.php. St. Augustine Intro/ Pedro Menendez Francis, J. Michael, and Glenn Hastings. St. Augustine America's First City: a Story of Unbroken History & Enduring Spirit. EÌ Ditions Du Signe, 2015. Gannon, M. (2012). The New History of Florida. University Press of Florida, 2012. Florida Heritage Trail: Spanish Fort Mose Francis, J. Michael, and Glenn Hastings. St. Augustine America's First City: a Story of Unbroken History & Enduring Spirit. EÌ Ditions Du Signe, 2015. Gannon, M. (2012). The New History of Florida Florida Spanish Colonial Heritage Trail = Herencia Colonial Espanola De Florida. Visit Florida, 2009. “Fort Mose.” Visit St. Augustine, https://www.visitstaugustine.com/thing-to-do/fort- mose. “Fort Mose---American Latino Heritage: A Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/american_latino_heritage/fort_mose.html. Castillo de San Marcos Francis, J. Michael, and Glenn Hastings. St. Augustine America's First City: a Story of Unbroken History & Enduring Spirit. EÌ•Ditions Du Signe, 2015. Gannon, M. -

The Rebbe Nachman of Braslav Is Famous for Saying: 'The Whole World

YK Sermon 5773 Shir Shalom Final AMLK 1 The Rebbe Nachman of Braslav is famous for saying: ‘The whole world is a narrow bridge, the key is not to be afraid” KOL HA’OLAM KULO GESHER TZAR ME’OD, VE’HA’IKAR LO LEFACHED CLAL I have often wondered what this famous Chasidic master, the grandson of the Ba’al Shem Tov, understood about bridges. What bridge did he have in mind when he spoke about a “Gesher Tzar Meod”? And how can we possibly cross over that bridge without being afraid? As to the bridge, perhaps, it was the bridge over the Southern Buh or Buzhok, rivers that intersected by his birthtown of Medzhybizh (MEDEZIBIZ). Or, perhaps, it was the floating bridge of Kiev. Originally built with wooden planks resting over boats lined from one shore to the other. It was both narrow and treacherous to the many soldiers and wayfarers who had been crossing it for six hundred years before Reb Nachman was even born. Or, further still, maybe he was inspired by a picture of the famed Carrick-a- Rede rope bridge of Northern Ireland. Swaying between the crevice of two cliffs, this bridge is still in use today. But in Nachman’s time, there were no guardrails protecting travelers from the jagged rocks below. But, perhaps, he was imagining an even narrower bridge – one so thin and fragile you could grasp it in one hand. And, one that a family just up the road from the Famous Rebbe in the Austro Hungarian Empire would use as part of their newly formed circus act. -

Lake Wales, Fl Beyond Belief Warner University Board of Trustees

THE Spring 2017 Royal THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF WARNER UNIVERSITY LAKE WALES, FL BEYOND BELIEF WARNER UNIVERSITY BOARD OF TRUSTEES REV. ROBERT QUAM Chairman Lake Wales, FL WARNER UNIVERSITY REV. ROBERT BECKLER 13895 Highway 27 Wichita, KS Lake Wales FL, 33859 REV. JAMES BROWN Decatur, GA 863-638-1426 MR. DEAN BURNETTI www.warner.edu Lakeland, FL MR. JAMES CLAUSSEN Lakeland, FL MR. MICHAEL DARBY Beckley, WV REV. JOSEPH DEHART Lake Placid, FL MR. JOHN DURHAM Editors: Corpus Christi, TX Monique Frandji SENATOR DENISE GRIMSLEY Leigh Ann Wynn Sebring, FL Kareen Pickett MR. WALLACE KETRON Kingsport, TN Photos/ Images: MR. STEVE MAXWELL Kayla Selander Frostproof, FL Emilio Giler REV. JONATHAN MCDIVITT Monique Frandji Morganton, NC Mike Potthast MRS. LAURA MOTIS Babson Park, FL Cover Photo by CAPTAIN ROBERT OAKMAN Kayla Selander Lake Wales, FL REV. MARK SHANER Layout Design: Anderson, IN Eric Kidd REV. ANTHONY WEIGER Birmingham, AL MR. JERRY WEIMER Lake Wales, FL MR. DAVID WELSHEIMER Anderson, IN JUDGE ROBERT WILLIAMS Lake Wales, FL Stay on my wheel… One of my passions outside of my time serving at Warner is riding my bike. I have been privileged to race and train with many high-end cyclists who compete around the world. Drafting is a key skill to learn when you are “on the wheel” of a teammate. Drafting saves about 30% of your energy. Think about it, working together makes you more productive and you can last longer in an endurance event. It’s been one year since the board selected us to serve as the third president of Warner University. -

Local Foods Good Choice for Growers, Consumers

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to OOPINIONPINION assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances. Thursday, March 22, 2012 | Publisher: Taylor Wood Hayes | President: Chuck Henderson | Editor: Eli Pace | Opinion Editor: Jennifer P. Brown COLUMNIST n Local foods An invitation good choice for murder? am glad to hear the Justice Department is looking into the killing of Trayvon IMartin. After all, if they can investi- for growers, gate the killing of innocent civilians in Afghanistan, they can do it in Florida. By now, you’ve probably heard about the 17-year-old’s death and its outrageously suspicious circumstances. It’s a story with consumers tragically familiar scenes, especially to those of us who have raised young black males: A young white man follows a “sus- Maybe in an ideal world where good picious-looking” black teenager, confronts nutrition and healthy activity are in- him, and kills him in “self-defense.” grained in our daily routines, many of What adds an extra edge and national us would grow a vegetable garden in the relevance to this tragic episode is the backyard or in a shared neighborhood Florida law under which the shooter plot each year. The green onions, lettuce claims self-defense. The “Stand Your and potatoes would have been planted Ground” law, promoted by the National earlier this month. These would be fol- Rifle Association and signed by then-Gov. -

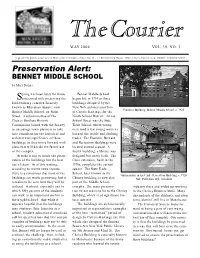

May 2004 Vol

The Courier MAY 2004 VOL. 39, NO. 3 A quarterly publication of the Manchester Historical Society, Inc. / 106 Hartford Road / Manchester, Connecticut 06040 / (860) 647-9983 Preservation Alert: BENNET MIDDLE SCHOOL by Mary Dunne pring has been busy for those Bennet Middle School Sconcerned with preserving the began life in 1914 as three four-building complex formerly buildings designed by the known as Education Square, now New York architectural firm Franklin Building, Bennet Middle School, c. 1925 Bennet Middle School, on Main of Carrere Hastings, for the Street. A subcommittee of the Ninth School District. Across Cheney Brothers Historic School Street was the State Commission joined with the Society Trade School, where young to encourage town planners to take men (and a few young women) into consideration the historical and learned the textile and drafting architectural significance of these trades. The Franklin, Barnard, buildings, as they move forward with and Recreation Buildings were plans that will decide the future use located around a quad. A of the complex. fourth building, a library, was At stake is not so much the preser- designed but never built. The vation of the buildings but the best Cone extension, built in the use of them. As of this writing, 1970s, completes the current according to recent news reports, square. The State Trade there is a consensus that most of the School, later known as the Gymnasium in East Side Recreation Building, c. 1920 buildings are worth preserving, but it Cheney building, is now also Note Palladian-style windows remains to be seen how they will be part of the Middle School utilized.