The Leicestershire Historian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lutterworth Settlement Profile Introduction

Lutterworth Settlement Profile Introduction General Location: Lutterworth is located just of Junction 20 of the M1 in the south west of Harborough District, 7 miles north of Rugby and 15 miles south of Leicester City Centre. The motorway forms the eastern boundary of the settlement, although the parish extends beyond. Much of the southern parish boundary follows the River Swift which skims the southern edge of the town. The south western boundary follows the line of the A5. Whilst Magna Park Distribution Centre is partially within the parish, the majority lies in neighbouring Bitteswell with Bittesby parish. The Lutterworth southern bypass links Magna Park directly to the M1, effectively forming the southern limit of the town. Lutterworth is one of two market towns in the District, the other being Market Harborough some 12 miles to the east. Due to its position in between Rugby and Leicester, Lutterworth was important in the days of coaches and horses and the survival of a number of coaching inns that bear witness to this. The town also contains some historic half-timbered buildings, some of which date back to the 16th century. The town expanded rapidly with the introduction of the railway in 1899. Lutterworth station on the Great Central Railway closed along with the railway in 1969. Some of the dismantled railway line still survives between the town and the M1. Lutterworth is identified as a Key Centre in the Core Strategy, along with Broughton Astley. As a Key Centre its role is to provide additional housing, employment, retail, leisure and community facilities to serve its own community and those in its catchment area, in a manner which seeks to create a more attractive environment for businesses and visitors to the town centre. -

Gilmorton Settlement Profile Introduction

Gilmorton Settlement Profile Introduction General Location: Gilmorton village lies 3 miles north-east of Lutterworth. Leicester is 10 miles north, whilst Market Harborough is 15 miles to the east of the parish. Gilmorton is bordered by Ashby Magna and Peatling Parva to the north, Kimcote and Walton to the east, Misterton with Walcote to the south, with Lutterworth, Bitteswell and Ashby Parva to the west The north-east of the parish is occupied by Bruntingthorpe airfield, a now defunct RAF base that is home to an Aircraft museum and is now used for both aviation and non-aviation purposes. The village is broadly linear in form, running for over 1km north-south along Main Street. It is situated in a gently undulating landscape and is of Saxon origin. The parish lies on a watershed with streams rising to the north flowing into the North Sea via the Humber whilst those to the south flow in southwards to the Bristol Channel. Gilmorton always has been, and to some extent still is an agricultural village, but the relative decline of this industry has led to the area increasingly becoming a commuter village. The village has seen a long, steady decline in its public transport provision over the years, leaving only a twice-daily taxi-bus service to Lutterworth in the present day. A similar decline has occurred with the provision of shops/services in the village, but fortunately for many residents Gilmorton has managed to retain its village store, heralded as one of the best in Leicestershire. The village is identified as a Selected Rural Village in the Core Strategy for the District and as such, is outlined as a settlement that would potentially benefit from the support of limited development such as rural housing. -

Proposed Mineral Allocation Site on Land Off Pincet Lane, North Kilworth, Leicestershire

Landscape and Visual Appraisal for: Proposed Mineral Allocation Site on Land off Pincet Lane, North Kilworth, Leicestershire Report Reference: CE - NK-0945-RP01a- FINAL 26 August 2015 Produced by Crestwood Environmental Ltd. Crestwood Report Reference: CE - NK-0945-RP01a- FINAL: Issued Version Date Written / Updated by: Checked & Authorised by: Status Produced Katherine Webster Karl Jones Draft v1 17-08-15 (Landscape Architect) (Director) Katherine Webster Karl Jones Final 18-08-15 (Landscape Architect) (Director) Katherine Webster Karl Jones Final Rev A 26-08-15 (Landscape Architect) (Director) This report has been prepared in good faith, with all reasonable skill, care and diligence, based on information provided or known available at the time of its preparation and within the scope of work agreement with the client. We disclaim any responsibility to the client and others in respect of any matters outside the scope of the above. The report is provided for the sole use of the named client and is confidential to them and their professional advisors. No responsibility is accepted to others. Crestwood Environmental Ltd. Units 1 and 2 Nightingale Place Pendeford Business Park Wolverhampton West Midlands WV9 5HF Tel: 01902 824 037 Email: [email protected] Web: www.crestwoodenvironmental.co.uk Landscape and Visual Appraisal Proposed Quarry at Pincet Lane, North Kilworth CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 2 1.1 SITE -

Listado De Internados En Inglaterra

INGLATERRA COLEGIOS INTERNADOS PRECIOS POR TERM (4 MESES) MÁS DE 350 COLEGIOS Tarifas oficiales de los colegios internados añadiendo servicio de tutela en Inglaterra registrado en AEGIS a partir de £550 por term cumpliendo así con la legislación inglesa actual y con el estricto código de buenas prácticas de estudiantes internacionales Precio 1 Term Ranking Precio 1 Term Ranking Abbey DLD College London £8,350 * Boundary Oak School £7,090 * Abbots Bromley School £9,435 290 Bournemouth Collegiate £9,100 382 Abbotsholme School £10,395 * Box Hill School £10,800 414 Abingdon School £12,875 50 Bradfield College £11,760 194 Ackworth School £8,335 395 Brandeston Hall £7,154 * ACS Cobham £12,840 * Bredon School £9,630 * Adcote School £9,032 356 Brentwood School £11,378 195 Aldenham School £10,482 * Brighton College £13,350 6 Aldro School £7,695 * Bromsgrove School £11,285 121 Alexanders College £9,250 0 Brooke House College £9,900 * Ampleforth College £11,130 240 Bruton School for Girls £9,695 305 Ardingly College £10,710 145 Bryanston School £11,882 283 Ashbourne College £8,250 0 Burgess Hill School for Girls £10,150 112 Ashford School £11,250 254 Canford School £11,171 101 Ashville College £9,250 355 Casterton Sedbergh Prep £7,483 * Badminton School £11,750 71 Caterham School £10,954 65 Barnard Castle School £8,885 376 Catteral Hall £7,400 * Barnardiston Hall Prep £6,525 * Cheltenham College £11,865 185 Battle Abbey School £9,987 348 Chigwell School £9,310 91 Bede's £11,087 296 Christ College Brecon £8,994 250 Bede's Prep School £8,035 * Christ's -

Breakdown of COVID-19 Cases in Leicestershire

Weekly COVID-19 Surveillance Report in Leicestershire Cumulative data from 01/03/2020 - 05/05/2021 This report summarises the information from the surveillance system which is used to monitor the cases of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Leicestershire. The report is based on daily data up to 5th May 2021. The maps presented in the report examine counts and rates of COVID-19 at Middle Super Output Area. Middle Layer Super Output Areas (MSOAs) are a census based geography used in the reporting of small area statistics in England and Wales. The minimum population is 5,000 and the average is 7,200. Disclosure control rules have been applied to all figures not currently in the public domain. Counts between 1 to 5 have been suppressed at MSOA level. An additional dashboard examining weekly counts of COVID-19 cases by Middle Super Output Area in Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland can be accessed via the following link: https://public.tableau.com/profile/r.i.team.leicestershire.county.council#!/vizhome/COVID-19PHEWeeklyCases/WeeklyCOVID- 19byMSOA Data has been sourced from Public Health England. The report has been complied by Strategic Business Intelligence in Leicestershire County Council. Weekly COVID-19 Surveillance Report in Leicestershire Cumulative data from 01/03/2020 - 05/05/2021 Breakdown of testing by Pillars of the UK Government’s COVID-19 testing programme: Pillar 1 + 2 Pillar 1 Pillar 2 combined data from both Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 data from swab testing in PHE labs and NHS data from swab testing for the wider -

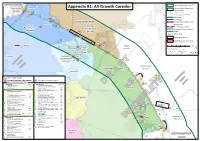

Appendix B1: A5 Growth Corridor

5km Distance buffer from A5 STAFFORDSHIREA 1 5 1 Polesworth Tamworth Appendix B1: A5 Growth Corridor Areas of Recent Major Road Improvements: Borough 2 A A5 / A444 / A47 - MIRA 4 2 47 A B M1 / M6 / A14 - Catthorpe Interchange (to be completed Autumn 2016) 69 3 4 M 5 4 4 4,5 A Motorways Trunk Roads 3 7 8 ! 42 Current Railway Stations and M LEICESTERSHIRE Atherstone Earl Shilton Railway Lines North 6 7 Hinckley 69 ! Warwickshire 6 A5 M Future Railway Stations and Bosworth HS2 Route (Phases 1 and 2) Borough A47 Borough Canals 21 25 Urban Areas A M 1 County Boundaries 8 A 22 Hinckley 11 District/Borough Boundaries 25 (Coloured administrative areas show "LEP City Deal" areas.) 13,14,15,16 23 10 9 A47 0 1 2 3 4 5 1:55,000 9 24 (When printed at 10 12 Blaby A1 paper size.) SOLIHULL 11 Kilometres Nuneaton District This map is for illustrative purposes only. ´ 12 © Crown Copyright and database right 2015. Ordnance Survey 100019520. 4 Produced by the WCC Corporate 4 4 GIS Team, A 13 69 25 June, 2015. M 15 14 Coleshill Nuneaton 16 and Bedworth A 1 17 5 M Borough Harborough WARWICKSHIRE District Bedworth 26 M6 28 D Current Employment Sites 29 D Future Employment Sites / Major Expansion 8 Future Major Housing Developments Lutterworth Red text signifies those sites without full planning permission 9 6 M Future Employment Staffordshire: Figures: Warwickshire: Housing Units: 27 Tamworth Borough: = Development Site North Warwickshire Borough: Rugby A45 * in Warwickshire 1 Relay Park - 1 Land on South Side of Grendon Road 143 2 Centurion Park 421 * 2 Orchard, Dordon 360 Borough 3 Dairy House Farm, Spon Lane 85 Warwickshire: 4 Land at Old Holly Lane including Durno's 620 A 4 North Warwickshire Borough: Nurseries 4 3 Kingsbury Link - 5 Rowland Way 88 4 4 Hall End Farm 750 6 Britannia Works, Coleshill Road 54 5 Birch Coppice (Phases 1-3) (inc. -

94: Leicestershire Vales Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 94: Leicestershire Vales Area profile: Supporting documents www.naturalengland.org.uk 1 National Character 94: Leicestershire Vales Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment White Paper1, Biodiversity 20202 and the European Landscape Convention3, we are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas (NCAs). These are areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision-making framework for the natural environment. NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform their decision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The information they contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a landscape scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage broader partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will also help to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental Opportunity (SEOs) are suggested, which draw on this integrated information. The SEOs offer guidance on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. 1 The Natural Choice: Securing the Value of Nature, Defra NCA profiles are working documents which draw on current evidence and (2011; URL: www.official-documents.gov.uk/document/cm80/8082/8082.pdf) 2 knowledge. -

Potential Sites to Deliver Housing Allocations for Selected Options

The assessment of potential sites to deliver the housing allocations for the Selected Options Potential sites to deliver housing allocations for selected options . The assessment of potential sites to deliver the housing allocations for the Selected Options Page 3 Potential sites to deliver housing allocations for selected options . The assessment of potential sites to deliver the housing allocations for the Selected Options Page 4 Table of Contents 1 Introduction...................................................................................................................... 1 2 Assumptions .................................................................................................................... 2 3 Site Selection Process..................................................................................................... 3 4 Option 2 - Core Strategy.................................................................................................. 6 5 Option 4 - SDA at Scraptoft North ................................................................................. 16 6 Option 5 - SDA at Kibworth............................................................................................ 25 7 Option 6 - SDA at Lutterworth........................................................................................ 34 8 Conclusions................................................................................................................... 42 9 Appendix 1 Housing requirements by Settlement for the Selected Options................. -

Leire | Lutterworth | Leicestershire | LE17 5HL the MOP TOPS

The Mop Tops The Green | 8 Leire Road | Leire | Lutterworth | Leicestershire | LE17 5HL THE MOP TOPS Situated on a quite no-through road in the delightful and sought after village of Leire is The Mop Tops, a large and beautifully presented family home that was built in 2000. Accommodation Summary Ground Floor Steps lead up to the double front doors which open into the reception hall, with a rear glazed elevation enjoying views over the expansive lawn gardens; a grand staircase rises to a spacious gallery landing. Concertina timber doors open into the bespoke kitchen breakfast room hand-made by Brookman of Sheffield, with an excellent range of units, stainless still sink, fitted dish-washer, butler’s sink, Aga 6/4 into inglenook, granite/ oak work surfaces, fitted unit housing American style fridge/freezer; an arch leads into a cosy sitting room with French doors to terrace. Off the kitchen is a useful walk-in pantry. The dining room has a stone floor and French doors to the terrace and a useful store room. From the dining room double doors lead into the drawing room, which is a fabulous space with arched windows and French doors to terrace and steps up to a mezzanine which would be ideal as a library, the inglenook fireplace has a log burner and bressumer beam. The utility room is fitted with floor/wall units, work surface, spaces for washing machine/tumble drier, butler’s sink. Off the utility is a cloaks room and a separate cloakroom. There is also a further cloakroom and a study to the ground floor. -

GILMORTON NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN: 2018-2031 Gilmorton Neighbourhood Plan: Submission

F GILMORTON NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN: 2018-2031 Gilmorton Neighbourhood Plan: Submission Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 Neighbourhood Plans ...................................................................................................................... 1 The Gilmorton Neighbourhood Plan Area ........................................................................................ 1 What has been done so far ............................................................................................................... 2 What happens next? ........................................................................................................................ 4 Sustainable Development ................................................................................................................ 4 Key Issues ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Vision ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Implementation ............................................................................................................................... 6 2. Rural Character ............................................................................................................................ 7 Countryside ..................................................................................................................................... -

Speaker Information 2019 WLSA Global Educators Conference

Speaker information 2019 WLSA Global Educators Conference Page | 1 Gail BERSON Title: Director of College Counseling Institution: Lycée Français de New York Biography: Gail Berson is the Director of College Counseling at the Lycée Français de New York. She has more than 40 years of experience in college admission, student financial services, and counseling. A magna cum laude graduate of Bowdoin College, she earned her master’s degree at Emerson College. She served as Vice President for Enrollment/Dean of Admissions. n and Financial Aid at Mount Holyoke and Wheaton Colleges, as Director of Admission at Mills College (CA), interim college counselor at Rocky Hill School (RI), and has consulted broadly at a variety of colleges and independent schools. Ms. Berson, who has been a frequent speaker on college admission, is a former trustee of the College Board and currently volunteers for the World Leading Schools Theresa BLAKE Association (WLSA) where she presented sessions at their summer programs in Shanghai, China and on Jeju Island and in Seoul, Korea. She also served as a past president of the Bowdoin Alumni Council and in leadership roles for her class reunions. During vacations, she enjoys spending time with family and friends at her home on Nantucket. Title: Director of Social and Emotional Learning Institution: Appleby College Biography: Theresa Blake, M.Ed. CAPP, is the Director of Positive Education at Appleby College and is responsible for increasing faculty capacity to foster student wellbeing through theory and practice of Positive Education. Throughout her very successful teaching career, she has taught Mathematics, Sciences and French as a Second Language, and has served in multiple leadership capacities including Department Head of Languages, Director of Senior School and Director of Social and Emotional Learning (SEL). -

UK IB School Ranking (By Cohort Size)

UK IB School Ranking (by Cohort Size) Avg. Name Day/Board Boy/Girl Day £ Board £ Cohort Points Sevenoaks School Both Co-ed 24,516 37,404 205 39.6 United World College of the Atlantic Both Co-ed 168 35 St Clare's - Oxford Both Co-ed 17,967 37,052 115 35.9 King Edward's School (Boys) - Birmingham Day Boys 12,375 111 39.2 ACS Cobham International School Both Co-ed 25,680 44,360 97 29.9 Wellington College - Berkshire Both Co-ed 27,120 37,110 91 38.9 King's College - Wimbledon Day Co-ed 20,400 72 41.5 Oakham School - Rutland Both Co-ed 19,350 31,575 60 37.2 Haileybury - Hertford Both Co-ed 23,802 31,674 58 37.4 Southbank Intl School - Westminster Annexe Day Co-ed 27,660 55 35 St Leonards School - Fife Both Co-ed 13,137 32,040 54 34 King Edward's Witley Both Co-ed 19,950 29,595 51 33.4 TASIS - The American School in England Both Co-ed 22,510 39,500 50 33.9 King William's College - Castletown Both Co-ed 21,036 30,435 49 32.2 Ardingly College - Haywards Heath Both Co-ed 23,160 32,130 47 39 Marymount International School Both Girls 22,035 37,360 44 36.3 Christ's Hospital - Horsham Both Co-ed 20,490 31,500 39 36.6 ACS Hillingdon International School Day Co-ed 23,110 39 31.9 ACS Egham International School Day Co-ed 24,020 38 35.5 Felsted School - Essex Both Co-ed 22,125 32,985 37 33.9 Cheltenham Ladies' College Both Girls 26,220 38,670 36 40 Scarborough College - N.