Next System Media: an Urgent Necessity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

They Hate US for Our War Crimes: an Argument for US Ratification of the Rome Statute in Light of the Post-Human Rights

UIC Law Review Volume 52 Issue 4 Article 4 2019 They Hate U.S. for Our War Crimes: An Argument for U.S. Ratification of the Rome Statute in Light of the ost-HumanP Rights Era, 53 UIC J. MARSHALL. L. REV. 1011 (2019) Michael Drake Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, International Humanitarian Law Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Michael Drake, They Hate U.S. for Our War Crimes: An Argument for U.S. Ratification of the Rome Statute in Light of the Post-Human Rights Era, 53 UIC J. MARSHALL. L. REV. 1011 (2019) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol52/iss4/4 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THEY HATE U.S. FOR OUR WAR CRIMES: AN ARGUMENT FOR U.S. RATIFICATION OF THE ROME STATUTE IN LIGHT OF THE POST-HUMAN RIGHTS ERA MICHAEL DRAKE* I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................... 1012 II. BACKGROUND ............................................................ 1014 A. Continental Disparities ......................................... 1014 1. The International Process in Africa ............... 1014 2. The National Process in the United States of America ............................................................ 1016 B. The Rome Statute, the ICC, and the United States ................................................................................. 1020 1. An International Court to Hold National Leaders Accountable ...................................................... 1020 2. The Aims and Objectives of the Rome Statute .......................................................................... 1021 3. African Bias and U.S. -

THE GLOBALGIRL MEDIA OVERVIEW “This Is Our World, and My Voice”

THE GLOBALGIRL MEDIA OVERVIEW “This is Our World, and My Voice” www.globalgirlmedia.org 1. MISSION STATEMENT GlobalGirl Media (GGM) develops the voice and media literacy of teenage girls and young women in under-served communities by teaching them to create and share digital journalism designed to ignite community activism and social change. Through mentoring, training and access to a worldwide network of online distribution partners, GlobalGirl Media harnesses the power of new digital media to empower young women to bring their often-overlooked perspectives onto the global media stage. GlobalGirl Media’s model is unique in that it pairs GlobalGirl news bureaus in U.S. cities with bureaus in international cities, creating a peer-to-peer global online network of girls. As of June 2012, GlobalGirl Media has implemented initiatives in seven cities in South Africa, Morocco and the United States, training more than 120 girls and young women, who have produced 125 video features using traditional camera and sound; 85 mobile journalism pieces on I-pod touch devices; and 180 blog reports that were distributed through trans-media platforms, predominantly online, but also including print, broadcast TV and cable, cell phones, radio and social media. 2. OUR MODEL GlobalGirl Media partners with local non-profit and educational organizations to provide a rigorous, four-week program of education and training in new digital media and citizen journalism to groups of 15 to 20 girls, ages 16-21, who are selected in partnership with local NGOs and/or educational institutions. Instructed by seasoned media professionals, the girls first learn the fundamentals of journalism: identifying and telling a story; journalism ethics, using a camera, sound and technical equipment; digital/mobile story-telling; and social media as a tool for development. -

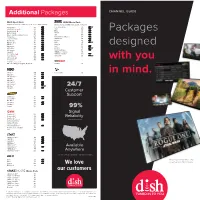

Packages Designed with You in Mind

Additional PackagesWe loveWe our love customers our customersCHANNEL GUIDE Multi-Sport Pack ™ DISH Movie Pack Requires subscription to America’s Top 120 Plus or higher24/7 package. 15 movie24/7 channels and 1000s99% of titles available On Demand.99% beIN SPORTS SAP 392 Crime & Investigation 249 beIN SPORTS en Español 873 CustomerEPIXCustomer 1 Signal380 Signal Big Ten Network 405 EPIX 2 381 * * Packages Big Ten Network 410 SupportEPIX SupportHits Reliability382Reliability Bases Loaded/Buzzer Beater/Goal Line 403We love FXMour customers384 FOX Sports 2 149 Hallmark Movies & Mysteries 187 1 HDNet Movies *Based on nationwide130 study of signal reception by DISH customersAvailable Longhorn Network 407 *Based on nationwide study of signal reception by DISH customersAvailable MLB Network 152 IndiePlex 378 MLB Strike Zone 153 MGM 385 Anywhere NBA TV SAP 156 MoviePlex 377 Anywhere NFL Network 154 PixL SAP 388 designed NFL RedZone 24/7155 99%RetroPlex 379 NHL Network 157 Sony Movie Channel 386 Outside TV Customer390 SignalSTARZ Encore Suspense 344 STARZ Kids & Family SAP 356 Pac-12 Network 406 * Pac-12 Network 409 Universal HD 247 SEC Network Support404 Reliability SEC Network SAP 408 with you 1 Only HD for live events. *Based on nationwide study of signal reception by DISH customersAvailable Plus over 25 Regional Sports Networks TheBlaze Anywhere212 HBO (E) SAP 300 Fox Soccer Plus 391 HBO2 (E) SAP 301 in mind. HBO Signature SAP 302 HBO (W) SAP 303 HBO2 (W) SAP 304 HBO Family SAP 305 HBO Comedy SAP 307 HBO Zone SAP 308 24/7 24/7 HBO Latino 309 -

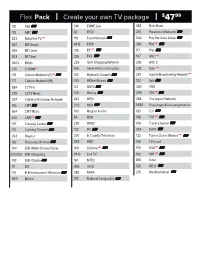

Flex Pack Create Your Own TV Package

Flex Pack C reate your own TV package $4799 118 A&E 134 EVINE Live 368 Nick Music 131 AMC 82 FETV 241 Paramount Network 823 BabyFirst TV SAP 110 Food Network 500 Pay-Per-View Guide 362 BET Gospel 9415 FSTV 388 PixL SAP 365 BET Jams 136 FX SAP 117 Pop 363 BET Soul 125 FXX 137 QVC SAP 9403 BYUtv 229 Gem Shopping Network 255 QVC 2 210 C-SPAN SAP 165 Great American Country 225 Sale SAP 176 Cartoon Network (E) SAP 185 Hallmark Channel 257 SonLife Broadcasting Network SAP 177 Cartoon Network (W) 130 HDNet Movies 122 Syfy 884 CCTV-E 112 HGTV 260 TBN 279 CCTV News 120 History 209 TBS SAP 267 Christian Television Network 843 HITN 268 The Impact Network 166 CMT 202 HLN 9393 Three Angels Broadcasting Network 364 CMT Music 103 Hopper Insider 183 TLC 200 CNN SAP 84 HSN 138 TNT SAP 107 Comedy Central 226 HSN2 196 Travel Channel 113 Cooking Channel 133 IFC 242 truTV 263 Daystar 230 In Country Television 132 Turner Classic Movies SAP 182 Discovery Channel 259 INSP 106 TV Land 100 DISH Multi-Channel View 108 Lifetime SAP 105 USA SAP 123/220/221 DISH Shopping 9410 Link TV 162 VH1 SAP 102 DISH Studio 161 MTV2 846 V-me 111 DIY 366 mtvU 128 WE tv 114 E! Entertainment Television 286 NASA 215 WeatherNation 9411 Enlace 197 National Geographic + 50 Starter Then add the Channel Packs you want like Locals, News, and Outdoor Channels Local Channels* $12/mo. Heartland Pack $6/mo. -

Alp Rate Card

DISH Network for Business, Hospitality and Multi-family Housing Page 1 of 1 Core Packages Max View News and Finance Entertainment Kids and Education DishLATINO Business Viewing DishLATINO Hospitality Viewing Local Broadcast Networks MAX VIEW (PUBLIC/PRIVATE) Monthly Price: $41.99 All Channels Family Education/Learning Religious Lifestyle Entertainment Movies Music Shopping News/Informational Sports Public Interest • ABC FAMILY • AMC • ANGEL ONE • ANIMAL PLANET • ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT • Alma Vision Hispanic Network • BBC AMERICA • BEAUTY & FASHION CHANNEL • BIOGRAPHY • BLACK ENTERTAINMENT TELEVISION • BLOOMBERG TELEVISION • BOOMERANG • BRAVO • BYUTV • C-SPAN • C-SPAN2 • CABLE NEWS NETWORK • CARTOON NETWORK • CCTV-9 • CCTV-E&F • CLASSIC ARTS SHOWCASE • CNBC • CNBC WORLD • COLLEGE SPORTS TELEVISION • COLOURS TV • COMEDY CENTRAL • COUNTRY MUSIC TELEVISION • COURT TV • DAYSTAR • DISCOVERY CHANNEL, THE • DISCOVERY HEALTH • DISCOVERY HOME • DISCOVERY KIDS • DISCOVERY TIMES CHANNEL • DO IT YOURSELF • DOCUMENTARY CHANNEL • E! ENTERTAINMENT TELEVISION • ETERNAL WORD TELEVISION NETWORK • Educator TV • FEC/PAEC • FINE LIVING • FOOD NETWORK • FOX NEWS CHANNEL • FREE SPEECH TV • FUSE • FX • G4 • GALAVISION • GAME SHOW NETWORK • GOOD SAMARITAN NETWORK • GREAT AMERICAN COUNTRY • HEADLINE NEWS NETWORK • HISTORY CHANNEL INTERNATIONAL • HISTORY CHANNEL, THE • HITN • HOME & GARDEN TELEVISION • HORSERACING TV • HSN • Health & Human Services Television • INDEPENDENT FILM CHANNEL • ION • KBS WORLD • LEARNING CHANNEL, THE • LIFETIME • LINK TV • MILITARY CHANNEL -

List of Directv Channels (United States)

List of DirecTV channels (United States) Below is a numerical representation of the current DirecTV national channel lineup in the United States. Some channels have both east and west feeds, airing the same programming with a three-hour delay on the latter feed, creating a backup for those who missed their shows. The three-hour delay also represents the time zone difference between Eastern (UTC -5/-4) and Pacific (UTC -8/-7). All channels are the East Coast feed if not specified. High definition Most high-definition (HDTV) and foreign-language channels may require a certain satellite dish or set-top box. Additionally, the same channel number is listed for both the standard-definition (SD) channel and the high-definition (HD) channel, such as 202 for both CNN and CNN HD. DirecTV HD receivers can tune to each channel separately. This is required since programming may be different on the SD and HD versions of the channels; while at times the programming may be simulcast with the same programming on both SD and HD channels. Part time regional sports networks and out of market sports packages will be listed as ###-1. Older MPEG-2 HD receivers will no longer receive the HD programming. Special channels In addition to the channels listed below, DirecTV occasionally uses temporary channels for various purposes, such as emergency updates (e.g. Hurricane Gustav and Hurricane Ike information in September 2008, and Hurricane Irene in August 2011), and news of legislation that could affect subscribers. The News Mix channels (102 and 352) have special versions during special events such as the 2008 United States Presidential Election night coverage and during the Inauguration of Barack Obama. -

Pacifica Radio Syndicated Program Directory

PACIFICA RADIO SYNDICATED PROGRAM DIRECTORY The following programs are distributed through the Pacifica network. Some are produced by Pacifica stations or the network itself; others are independent productions that use Pacifica distribution channels. To suggest additions or changes to this guide for future editions, write to Pacifica Network Affiliates Coordinator Ursula Ruedenberg, [email protected]. WEEKLY PROGRAMS (30-60 min) Alternative Radio New Dimensions Are We Alone? Off The Hook Behind the News Poetswest Between the Lines Sea Change Radio Bookwaves Sierra Club Radio Brain Labor Report Sojourner Truth Radio Building Bridges Song of the Soul Century of Lies Spirit in Action Corporate Watchdog Radio Spoiler Alert Radio Counterspin Sprouts Cultural Baggage Taking Aim Earthbeat Talk Nation Radio Electromatic Radio The 300-350 Show (Climate Radio) Encounters The Global Report Exploration This Way Out Flashpoints (Best of) Time of Useful Consciousness From the Vault Uprising GRIT Radio Urban Herbalist Indigenous Politics We News Law and Disorder What's At Stake Madness Radio WINGS Making Contact Writer's Voice Midweek Politics Yin Radio MyNDTALK Your Own Health And Fitness DAILY PROGRAMS (30-60 min) Against the Grain (3 days/week) Free Speech Radio News Brain Labor Report Hard Knock Radio Democracy Now! Informativo Pacifica Flashpoints MODULES WEEKLY PROGRAM MODULES (<10 min) Black Agenda Report Peak Oil Check-In Media Minutes Weekly Radio Spin DAILY PROGRAM MODULES (<10 min) 4:20 Drug War News Workers Independent News Jim Hightower’s Commentaries AGAINST THE GRAIN Program logo courtesy of KPFA C.S. Soong PROGRAM DESCRIPTION Against the Grain features intelligent, in-depth interviews with progressive and radical scholars and activists. -

Julian E. Zelizer

Julian E. Zelizer Julian E. Zelizer Department of History and Woodrow Wilson School Princeton University 136 Dickinson Hall Princeton, NJ 08544-1174 Phone: 609-258-8846 Cell Phone: 609-751-4147 Department FAX: 609-258-5326 Faculty Appointments Professor of History and Public Affairs, Princeton University, 2007-Present. Faculty Associate, Center for the Study for the Study of Democratic Politics, 2007-Present. Professor of History, Boston University, 2004-2007. Faculty Associate, Center for American Political Studies, Harvard University, 2004-2007. Associate Professor, Department of Public Administration and Policy, State University of New York at Albany, 2002-2004. Joint appointment with the Department of Political Science. Affiliated Faculty, Center of Policy Research, State University of New York at Albany, 2002- 2004. Associate Professor, Department of History, State University of New York at Albany, 1999- 2002. Joint Appointment with Department of Public Administration and Policy, 1999-2002. Assistant Professor, Department of History, State University of New York at Albany, 1996- 1999. Education Ph.D., Department of History, The Johns Hopkins University, 1996. M.A., with four Distinctions, Department of History, The Johns Hopkins University, 1993. B.A., Summa Cum Laude with Highest Honors in History, Brandeis University, 1991. Editorial Positions Co-Editor, Politics and Society in Twentieth Century America book series, Princeton University Press, 2002-Present. Editorial Board, The Journal of Policy History, 2002-Present. Books Jimmy Carter (New York: Times Books, Forthcoming, Fall 2010). 2 Conservatives in Power: The Reagan Years, 1981-1989 (Boston: Bedford, Forthcoming, Fall 2010). Arsenal of Democracy: The Politics of National Security--From World War II to the War on Terrorism (New York: Basic Books, 2010). -

Stream Live TV

CHANNELS AVAILABLE TO YOU CHANNELS AVAILABLE TO YOU THROUGH STREAMING TV. THROUGH STREAMING TV. CBS WDBJ Food Network CBS WDBJ Food Network MYN WZBJ TV Land MYN WZBJ TV Land RU Information Syfy Channel RU Information Syfy Channel NBC WSLS BBC America NBC WSLS BBC America PBS WBRA Paramount Network PBS WBRA Paramount Network PBS World / Encore BET PBS World / Encore BET FOX WFXR A&E FOX WFXR A&E CW WWCW FX CW WWCW FX ABC WSET FXX ABC WSET FXX ION Television USA Network ION Television USA Network HLN Motor Trend HLN Motor Trend CNN Weather Channel CNN Weather Channel CNBC Travel Channel CNBC Travel Channel MSNBC TLC MSNBC TLC Bloomberg Television History Channel Bloomberg Television History Channel Fox News Channel National Geographic Fox News Channel National Geographic Fox Business Network Discovery Channel Fox Business Network Discovery Channel CSPAN Freeform CSPAN Freeform Free Speech TV Hallmark Channel Free Speech TV Hallmark Channel Link TV POP TV Link TV POP TV AXS AMC AXS AMC FM ReelzChannel FM ReelzChannel CMT IFC CMT IFC Fuse Pursuit Fuse Pursuit VH1 Tru TV VH1 Tru TV MTV TBS MTV TBS MTV Live TNT MTV Live TNT MTV2 Golf Channel MTV2 Golf Channel Disney Channel NHL Network Disney Channel NHL Network Disney XD NBA TV Disney XD NBA TV Nickelodeon MLB Network Nickelodeon MLB Network TeenNick NFL Network TeenNick NFL Network Cartoon Fox Sports 1 Cartoon Fox Sports 1 E! Entertainment NBC Sports Network E! Entertainment NBC Sports Network Comedy Central ESPN Comedy Central ESPN Animal Planet ESPN2 Animal Planet ESPN2 Lifetime ESPNews Lifetime ESPNews OWN ESPNU OWN ESPNU Bravo CheddarU Bravo CheddarU HGTV HGTV . -

In the Battle for Reality (PDF)

Showcasing and analyzing media for social justice, democracy and civil society In the Battle for Reality: Social Documentaries in the U.S. by Pat Aufderheide Center for Social Media School of Communication American University December 2003 www.centerforsocialmedia.org Substantially funded by the Ford Foundation, with additional help from the Phoebe Haas Charitable Trust, Report available at: American University, and Grantmakers www.centerforsocialmedia.org/battle/index.htm in Film and Electronic Media. 1 Acknowledgments The conclusions in this report depend on expertise I have Events: garnered as a cultural journalist, film critic, curator and International Association for Media and academic. During my sabbatical year 2002–2003, I was able to Communication Research, Barcelona, conduct an extensive literature review, to supervise a scan of July 18–23, 2002 graduate curricula in film production programs, and to conduct Toronto International Film Festival, three focus groups on the subject of curriculum for social September 7–13, 2002 documentary. I was also able to participate in events (see sidebar) and to meet with a wide array of people who enriched Pull Focus: Pushing Forward, The National this study. Alliance for Media Arts and Culture conference, Seattle, October 2–6, 2002 I further benefited from collegial exchange with the ad-hoc Intellectual Property and Cultural Production, network of scholars who also received Ford grants in the same sponsored by the Program on Intellectual time period, and from interviews with many people at -

What Is Democracy Now! 010510

Democracy Now!, is an international, independent, daily news hour, hosted by award-winning journalists Amy Goodman and Juan Gonzalez. By featuring a rich diversity of voices often ignored by the corporate media, Democracy Now! presents in-depth information, historical perspectives, and substantive public debate on the most pressing issues of the day. What began in 1996 as a daily election program on a dozen community radio stations has rapidly grown into the largest public media collaboration in North America. Democracy Now! is broadcast in English and in Spanish on more than 800 radio and television stations across the country. The program airs on Pacifica, NPR stations, low power FM, College and Community Radio stations as well as Public Access TV and PBS stations, and on both TV satellite networks -- DISH Network channel 9415 Free Speech TV, 9410 Link TV, and on Direct TV channel 375. The program -- in audio, video and transcript form -- is also available in its entirety on the internet. Time Magazine named Democracy Now! its “Pick of the Podcasts,” along with NBC’s Meet the Press. Democracy Now! continues to attract public awareness and professional recognition for its work. As a growing number of authors introduce their books on the program, Crain’s cited Democracy Now! for propelling political books onto bestseller lists. In the past year, Democracy Now! was featured in O Magazine, Le Monde diplomatique, The Washington Post, and The International Herald Tribune. Democracy Now! accepts no advertising income, corporate underwriting, or government funding. The program has grown, and maintained its editorial independence through the generous support of its dedicated audience and committed donors. -

DIRECTV CHANNEL LINEUP ALPHABETICAL Available Channels on Your DIRECTV System

DIRECTV CHANNEL LINEUP ALPHABETICAL Available channels on your DIRECTV system. NETWORK CHANNEL PACKAGE NETWORK CHANNEL PACKAGE NETWORK CHANNEL PACKAGE NETWORK CHANNEL PACKAGE 3net ..................... 3D 107 llll HITN* TV ...................... 449 llll WE: Women’s Entertainment ....... 260 llll FS Southwest ............. h 676 A&E ..................... h 265 llll Home & Garden Television .... h 229 llll WGN America .............. h 307 llll FS West .................. h 692 ABC Family ................ h 311 llll Home Shopping Network ......... 240 llll Word, The ..................... 373 llll MSG, Madison Square Garden . h 634 Al Jazeera America .............. 358 llll Hope Channel, The* ............. 368 llll World Harvest Television .......... 367 llll Madison Square Garden Plus .. h 635 AMC ..................... h 254 llll HUB .......................... 294 llll MASN, Mid-Atlantic Sports .... h 640 American Heroes Channel ......... 287 llll Independent Film Channel .... h 564 llll premium services Animal Planet .............. h 282 llll Inspiration Network ............. 364 llll New England Sports Network .. h 628 AUDIENCE Network ......... h 239 llll Investigation Discovery ....... h 285 llll CINEMAX Outdoor Channel ................ 606 AXSTV HD .............. h 340 u llll ION TV East ................ h 305 llll MAX Latino ................ h 523 u ll Prime Ticket ................ h 693 BBC America ............... h 264 llll ION TV West ................... 306 llll 5StarMAX East ............. h 520 u ll ROOT SPORTS Northwest ....