ROGER BAILEY, Founder of Architecture at the University of Utah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

02Walk.Tour.Guts

North Downtown Heritage Tour The early history of Salt Lake City is dominated by the story of its Mormon settlers. These settlers came to Utah as a centrally-organized group dedicated to establishing their vision of a perfect society—the Kingdom of God on earth. Accordingly, there was no distinction between religious and secular life in early Salt Lake City. Leaders of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints directed the community’s economic life, shaped its social life, and even molded its family life. The north end of Salt Lake City’s downtown is a good place to view buildings and sites that reflect the city’s early Mormon heritage. Church leaders, cultural institutions, business enter- prises, and church offices tended to cluster near Temple Square, the geographic heart of the Mormon utopia. Within 20 years of Salt Lake City’s founding, the commu- nity began to diversify. The completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 made it much easier for immigrants from around the world to reach Utah. Not all the people who settled in Salt Lake City fit the Mormon vision of members of a perfect society. Nor did these new immigrants always share the Mormon community’s goals. This tour also highlights some of the buildings and sites that represent Salt Lake City’s growth and diversification after its settlement period. Your walk through north downtown’s history will take about one hour. The tour ends on Main Street just one half block south of the starting point at the Joseph Smith Memorial Building. -

Juanita Brooks Lecture Series

The DSU Library Presents the 37th annual JUANITA BROOKS LECTURE SERIES Presented by: Dr. Martha Bradley-Evans Constructing Zion: Faith, Grit and the Realm of Possibilities THE JUANITA BROOKS LECTURE SERIES PRESENTS THE 37TH ANNUAL LECTURE APRIL 1, 2020 DIXIE STATE UNIVERSITY Constructing Zion: Faith, Grit, and the Realm of Possibilities By: Dr. Martha Bradley-Evans Copyright 2020, Dixie State University St. George, Utah 84770. All rights reserved 2 3 Juanita Brooks Juanita Brooks was a professor at [then] Dixie College for many years and became a well-known author. She is recognized, by scholarly consensus, to be one of Utah’s and Mormondom’s most eminent historians. Her total honesty, unwavering courage, and perceptive interpretation of fact set more stringent standards of scholarship for her fellow historians to emulate. Dr. Obert C. and Grace Tanner had been lifelong friends of Mrs. Brooks and it was their wish to perpetuate her work through this lecture series. Dixie State University and the Brooks family express their thanks to the Tanner family. 5 the Honorary AIA Award from AIA Utah. In 2014 the Outstanding Achievement Award from the YWCA and was made a fellow of the Utah State Historical Society. She is the past vice chair of the Utah State Board of History, a former chair of the Utah Heritage Foundation. Dr. Bradley’s numerous publications include: Kidnapped from that Land: The Government Raids on the Short Creek Polygamists; The Four Zinas: Mothers and Daughters on the Frontier; Pedastals and Podiums: Utah Women, Religious Authority and Equal Rights; Glorious in Persecution: Joseph Smith, American Prophet, 1839- 1844; Plural Wife: The Autobiography of Mabel Finlayson Allred, and Glorious in Persecution: Joseph Smith, American Prophet 1839-44 among others. -

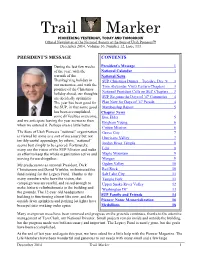

Trail Marker

Trail Marker PIONEERING YESTERDAY, TODAY AND TOMORROW Official Newsletter of the National Society of the Sons of Utah Pioneers™ December 2014, Volume 10, Number 12, Issue 113 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE CONTENTS During the last few weeks President’s Message 1 of the year, with the National Calendar 3 warmth of the National News Thanksgiving holiday in SUP Christmas Dinner – Tuesday, Dec. 9 3 our memories, and with the Tom Alexander Visits Eastern Chapters 3 promise of the Christmas National President Calls on SLC Chapters … 3 holiday ahead, our thoughts are decidedly optimistic. SUP Re-joins the Days of ’47 Committee 4 The year has been good for Plan Now for Days of ’47 Parade 4 the SUP, in that some good Membership Report 5 has been accomplished, Chapter News some difficulties overcome, Box Elder 5 and we anticipate leaving the year no worse than Brigham Young 6 when we entered it. Perhaps even a little better. Cotton Mission 6 The Sons of Utah Pioneers “national” organization Grove City 7 is viewed by some as a sort of necessary but not Hurricane Valley 7 terribly useful appendage; by others, “national” Jordan River Temple 8 seems best simply to be ignored. Fortunately, many see the vision of the SUP Mission and make Lehi 8 an effort to keep the whole organization active and Maple Mountain 9 moving forward together. Morgan 9 My predecessors as national President, Dick Ogden Valley 10 Christiansen and David Wirthlin, orchestrated the Red Rock 10 fund-raising for the Legacy Fund. Thanks to the Salt Lake City 11 many members who have the vision, that Temple Fork 11 campaign was successful, and raised enough to Upper Snake River Valley 12 make historic refurbishments to the building and Washington DC 13 the grounds. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005

Journal of Mormon History Volume 31 Issue 3 Article 1 2005 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (2005) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 31 : Iss. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol31/iss3/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005 Table of Contents CONTENTS ARTICLES • --The Case for Sidney Rigdon as Author of the Lectures on Faith Noel B. Reynolds, 1 • --Reconstructing the Y-Chromosome of Joseph Smith: Genealogical Applications Ugo A. Perego, Natalie M. Myres, and Scott R. Woodward, 42 • --Lucy's Image: A Recently Discovered Photograph of Lucy Mack Smith Ronald E. Romig and Lachlan Mackay, 61 • --Eyes on "the Whole European World": Mormon Observers of the 1848 Revolutions Craig Livingston, 78 • --Missouri's Failed Compromise: The Creation of Caldwell County for the Mormons Stephen C. LeSueur, 113 • --Artois Hamilton: A Good Man in Carthage? Susan Easton Black, 145 • --One Masterpiece, Four Masters: Reconsidering the Authorship of the Salt Lake Tabernacle Nathan D. Grow, 170 • --The Salt Lake Tabernacle in the Nineteenth Century: A Glimpse of Early Mormonism Ronald W. Walker, 198 • --Kerstina Nilsdotter: A Story of the Swedish Saints Leslie Albrecht Huber, 241 REVIEWS --John Sillito, ed., History's Apprentice: The Diaries of B. -

7/Ft/Tfw X Signatuyfe/Of the Keeper Date J

NFS Form 10-900a OMB No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES CONTINUATION SHEET Section ___ Page __ SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 03000631 Date Listed: 7/11/2003 Sugar House LDS Ward Building Salt Lake UT Property Name County State Sugar House Business District MRA Multiple Name This property is determined eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding the National Park Service certification included in the nomination documentation^, ^ j f 'JJ 7/ft/tfW X Signatuyfe/of the Keeper Date_ J_ _. 'of*^ .C Action» Amended Items in Nomination: Significance: Religion is deleted as an area of significance. [A religious property cannot be eligible under the area of significance Religion simply because it was the place of religious services for a community or the oldest structure used by a religious group in a local area. Such properties would need to document significance in association with a specific event in the history of religion or a theme having secular scholarly recognition.] These revisions were confirmed with the UT SHPO office. DISTRIBUTION: National Register property file Nominating Authority (without nomination attachment) NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service n National Register of Historic Places MAY282003 Registration Form iNAT. REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and dist the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). -

One of the Great Strengths of the Church of Jesus Christ Of

A Firm Foundation David J. Whittaker 28 Mormon Administrative and Organizational History: A Source Essay ne of the great strengths of The Church of Jesus Christ of O Latter-day Saints is its institutional vitality. Expanding from six members in 1830 to fourteen million in 2010, its capacity to govern and manage an ever-enlarging membership with a bureaucracy flexible enough to provide for communication and growth but tight enough to ensure control and stability is an important but little-known story. The essential functions of the Church were doctrinally mandated from its earliest years, and the commands to keep records have assured that accounts of its activities have been maintained. Such historical records created the essential informational basis necessary to run the institu- tion. These records range from membership to financial to the institu- tional records of the various units of the Church, from the First Presi- dency to branches in the mission field. David J. Whittaker is the curator of Western and Mormon Manuscripts, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, and associate professor of history at Brigham Young University. A Firm Foundation The study of Latter-day Saint ecclesiology has been a challenge until recently. As yet, the best studies remain in scholarly monographs, often unknown or unavailable. It is the purpose of this essay to highlight this emerging literature by complementing the essays assembled in this volume. OUTLINE Historical Studies General Histories 1829–44 The Succession Crisis 1847–77 1878–1918 -

Hclassifi Cation Hlocation of Legal Description

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR SHEFT NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY » NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Brigham Young Academy AND/OR COMMON Brigham Young University Lower Campus LOCATION STREET&NUMBER Between 5th and 6th North Streets and Between University Avenue and 1st East _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT PrOVO, __ VICINITY OF 1 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Utah 1560 Utah 049 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE 2>DISTRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) -^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED -^COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH K.WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED XYES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: (OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Academy Square Associates STREET & NUMBER 1409 Lant-mer Square CITY. TOWN STATE Denver, __ VICINITY OF Colorado HLOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Ufah Counfy Records Office STREET & NUMBER Center and Universfty Streets CITY. TOWN STATE Provo Utah REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Utah Historic Sites Survey DATE 975 —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Utah State Historical Society CITY, TOWN STATE Salt Lake City Utah DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^.ORIGINAL SITE -^GOOD _RUINS J^ALTERED MOVED DATF —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE 1. The Brigham Young University lower Campus occupies the block between 500 and 600 North facing University Avenue. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form

FHR-8-300 (11-78) United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Utah State Fair Grounds and/or common 2. Location street & number Tenth and Ngaffefa Temple Streets not for publication 09 city, town Salt Lake City vicinity of congressional district 035 state Utah code 049 county code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district X public X occupied X agriculture museum X building(s) private unoccupied X commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process ^ yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Utah State Building Board street & number Room 116 State Capitol Building city, town Salt Lake City vicinity of state Utah courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Salt Lake City and County Building street & number 400 South State city, town Salt Lake City state Utah 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Utah Historic Sites Survey has this property been determined elegible? __ yes no date Summer 1980 federal ^ state county local depository for survey records Utah State Historical Society Utah city, town Salt Lake state 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered X original site ^ good ruins x altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Utah State Fairgounds is a seventy acre area on Salt Lake City's westside that has been the site of the annual Utah State Fair since 1902. -

History of the Construction of the Salt Lake Temple

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1961 History of the Construction of the Salt Lake Temple Wallace Alan Raynor Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Raynor, Wallace Alan, "History of the Construction of the Salt Lake Temple" (1961). Theses and Dissertations. 5061. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/5061 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. J c2ca HISTORYHISTORY OF THE constructionCONSTRUCTlonION OF THE SALT LAKE cuauTEGUTEMPLE A thesis presented to the department of history brigham young university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree master of science by wallace alan raynor august 1961 PREFACXA the constrwconstructiontioneionelon of theth salt lake templetempie10 ifis an in extricabiaricableridable alaraantalaraaeismaantancenc of utah and honaonhondon history finfyrFIRfromcas th taraanttaoaantwimmim naiukimat of ifits captionininceptionincaptioneftimeptim in 1847 until ifits cavlationcooplationcoopcomplation fortyfortyixsixdix caarayearsyaara latarlaterlatez ifits dloveadlovedevalopoantM acoiacolncoincoincidcoincidesidcid elelyeloflyclelyciely with thezheuhe politi- cal mdand ecieelconoadcconoadoim -

The Youngs at West Point

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2002 The Youngs at West Point J. Michael Hunter Brigham Young University - Provo, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the History of Christianity Commons, Military History Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Hunter, J. Michael, "The Youngs at West Point" (2002). Faculty Publications. 1408. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/1408 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Published by the Sons of Ut11h Pioneers PUBLISHER Pm/RkAtmls FEATURES ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER John w. AMmtm 2 Two SIDES OF BRIGHAM YOUNG PRESIDENT·ELECT /..-is Pk/i.ttU by Marilynne Todd Linford EDITOR Ir 6 A H ERITAGE OF ART MAGAZINI DISIGNIR Mahonri Mackintosh Young S....La/gml by Brandi Rainey EDITORIAL STAFF JemtifarAdmtu 16 SUSA YOUNG G ATES T hirteenth Apostle EDITORIAL by Janet Peterson ADVISORY 80ARD Dr. F. C/uula C-. Clutirmdn 22 ZINA YOUNG CARD Dr./. Elliol Ctlmnon A Sister and Friend to All Dr. R,,,,_,J E. &df.1-o Riduwd S. Frt171 by Janet Peterso WEBSITE DESIGN 'Patrida &:lttmlbl NATIONAL HIADQUARTIRS JJlll Eat 2920 SoutA s.11 ~'City, Uflllt &1109 (801) 484-4441 E-milil: ~,,.,,,, -~ PUBLISHED QUARTERLY Salt Lake City, Utah ~ 112.00 per,,-. Forrerints-1 ~ ~. f'l-amllld the SUP. MISSION STATEMENT Tiu Nlllional Society ofSons of UIM Pionem llontm etlrly """ ffKll'iml-tlay pioneers, w ,_,,""" olJer; for their faHh ;,, God. -

Reclamation and Collaboration in Joseph Smith’S Theology Making

ARTICLES “THE PERFECT UNION OF MAN AND WOMAN”: RECLAMATION AND COLLABORATION IN JOSEPH SMITH’S THEOLOGY MAKING Fiona Givens Any church that is more than a generation old is going to suffer the same challenges that confronted early Christianity: how to preach and teach its gospel to myriad peoples, nationalities, ethnic groups, and societies, without accumulating the cultural trappings of its initial geographical locus. As Joseph Milner has pointed out, the rescue of the “precious ore” of the original theological deposit is made particularly onerous, threatened as it is by rapidly growing mounds of accumulating cultural and “ecclesiastical rubbish.”1 This includes social accretions, shifting sen- sibilities and priorities, and the inevitable hand of human intermediaries. For Joseph Smith, Jr., the task of restoration was the reclamation of the kerygma of Christ’s original Gospel, but not just a return to the early Christian kerygma. Rather, he was attempting to restore the Ur- Evangelium itself—the gospel preached to and by the couple, Adam and Eve (Moses 6:9). In the present paper, I wish to recapitulate a common thread in Joseph’s early vision, one that may already be too 1. Joseph Milner, The History of the Church of Christ, vol. 2 (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1812), v.; Joseph Milner, The History of the Church of Christ, vol. 3 (Boston: Farrand, Mallory, and Co., 1809), 221. 1 2 Dialogue, Spring 2016 obscure and in need of excavation and celebration. Central to Joseph’s creative energies was a profound commitment to an ideal of cosmic as well as human collaboration. -

Inside the Salt Lake Temple: Gisbert Bossard's 1911 Photographs

ARTICLES AND ESSAYS Inside the Salt Lake Temple: Gisbert Bossard's 1911 Photographs Kent Walgren THE BANNER HEADLINE ON SUNDAY'S 17 September 1911 edition of the Salt Lake Tribune greeted morning readers: "Gilbert [sic] L. Bossard, Convert, is Named as One Who Photographed Interior of Salt Lake Temple. Re- venge Is Sought by Him after Trouble with the Church; Has Left the City." The sensational article began: No local news story published in recent years has caused so much com- ment as the exclusive story in yesterday's Tribune regarding the taking of photographic views in the Salt Lake Mormon temple by secret methods. ... The most important development of the day was the identification, through efforts of a Tribune representative, of the man who took the views. This man is Gilbert L. Bossard, a German convert to Mormonism, who fell out with the church authorities and secretly took the pictures in a spirit of revenge.1 For faithful Mormons, the thought that someone had violated the sacred confines of the eighteen-year-old Salt Lake temple, which he desecrated by photographing, was "considered as impossible as profaning the sa- cred Kaaba at Mecca."2 1. Unless otherwise stated, the sources for all quoted material are news stories in either the Salt Lake Tribune, 16-21 Sept. 1911, or in the Deseret Evening News, 16 Sept. 1911. Other ma- jor sources include James E. Talmage's personal journal, Talmage Papers, Archives and Manuscripts, Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah (hereafter Talmage Journal); materials in Scott Kenney Papers, Ms.