02Walk.Tour.Guts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Worth Their Salt, Too

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@USU Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2000 Worth Their Salt, Too Colleen Whitley Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Whitley, C. (2000). Worth their salt, too: More notable but often unnoted women of Utah. Logan: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Worth Their Salt, Too More Notable but Often Unnoted Women of Utah WORTH THEIR SALT, TOO More Notable but Often Unnoted Women of Utah Edited by Colleen Whitley UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Logan, Utah 2000 Copyright © 2000 Utah State University Press “Marion Davis Clegg: The Lady of the Lakes” copyright © 2000 Carol C. Johnson All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322-7800 All royalties from the sale of this book will be donated to support the Exhibits office of the Utah State Historical Society. Cover photos: Marion Davis Clegg, courtesy of Photosynthesis; Verla Gean FarmanFarmaian, courtesy of Gean FarmanFarmaian; Ora Bailey Harding, courtesy of Lurean S. Harding; Alberta Henry, courtesy of the Deseret News; Esther Peterson, courtesy of Paul A. Allred; Virginia Sorensen, courtesy of Mary Bradford Typography by WolfPack Printed in Canada Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Worth their salt, too : more notable but often unnoted women of Utah / edited by Colleen Whitley. -

Maude Adams and the Mormons

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2013-1 Maude Adams and the Mormons J. Michael Hunter Brigham Young University - Provo, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Hunter, J. Michael, "Maude Adams and the Mormons" (2013). Faculty Publications. 1391. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/1391 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Mormons and Popular Culture The Global Influence of an American Phenomenon Volume 1 Cinema, Television, Theater, Music, and Fashion J. Michael Hunter, Editor Q PRAEGER AN IMPRI NT OF ABC-CLIO, LLC Santa Barbara, Ca li fornia • Denver, Colorado • Oxford, England Copyright 2013 by ABC-CLIO, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mormons and popular culture : the global influence of an American phenomenon I J. Michael Hunter, editor. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-313-39167-5 (alk. paper) - ISBN 978-0-313-39168-2 (ebook) 1. Church ofJesus Christ of Latter-day Saints-Influence. 2. Mormon Church Influence. 3. Popular culture-Religious aspects-Church ofJesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. -

Juanita Brooks Lecture Series

The DSU Library Presents the 37th annual JUANITA BROOKS LECTURE SERIES Presented by: Dr. Martha Bradley-Evans Constructing Zion: Faith, Grit and the Realm of Possibilities THE JUANITA BROOKS LECTURE SERIES PRESENTS THE 37TH ANNUAL LECTURE APRIL 1, 2020 DIXIE STATE UNIVERSITY Constructing Zion: Faith, Grit, and the Realm of Possibilities By: Dr. Martha Bradley-Evans Copyright 2020, Dixie State University St. George, Utah 84770. All rights reserved 2 3 Juanita Brooks Juanita Brooks was a professor at [then] Dixie College for many years and became a well-known author. She is recognized, by scholarly consensus, to be one of Utah’s and Mormondom’s most eminent historians. Her total honesty, unwavering courage, and perceptive interpretation of fact set more stringent standards of scholarship for her fellow historians to emulate. Dr. Obert C. and Grace Tanner had been lifelong friends of Mrs. Brooks and it was their wish to perpetuate her work through this lecture series. Dixie State University and the Brooks family express their thanks to the Tanner family. 5 the Honorary AIA Award from AIA Utah. In 2014 the Outstanding Achievement Award from the YWCA and was made a fellow of the Utah State Historical Society. She is the past vice chair of the Utah State Board of History, a former chair of the Utah Heritage Foundation. Dr. Bradley’s numerous publications include: Kidnapped from that Land: The Government Raids on the Short Creek Polygamists; The Four Zinas: Mothers and Daughters on the Frontier; Pedastals and Podiums: Utah Women, Religious Authority and Equal Rights; Glorious in Persecution: Joseph Smith, American Prophet, 1839- 1844; Plural Wife: The Autobiography of Mabel Finlayson Allred, and Glorious in Persecution: Joseph Smith, American Prophet 1839-44 among others. -

News Release

News Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE SALT LAKE ACTING COMPANY PRESENTS PULITZER PRIZE FINALIST THE WOLVES, BY SARAH DELAPPE Production marks Utah premiere following successful mountings Off-Broadway [SALT LAKE CITY, UT, SEPT 26, 2018] - Salt Lake Acting Company (SLAC), Utah’s leading destination for brave contemporary theatre, proudly presents Sarah DeLappe’s THE WOLVES, playing October 10 – November 11, 2018. A finalist for the 2017 Pulitzer Prize in Drama, THE WOLVES was originally produced in 2016 at The Duke on 42nd Street by The Playwrights Realm in association with New York Stage & Film and Vassar’s Powerhouse Theatre season, before its Lincoln Center debut in 2017. Set on an indoor soccer field, THE WOLVES chronicles the warm-ups of a teenage girls’ soccer team, with all the physical, mental, and emotional waves that come along with being a young female athlete. The characters are funny and smart. The lightning fast dialogue flows and overlaps, challenging the audience to lean in to the fiery dynamics of the team. A deceptively simple setting lays the foundation for a play that examines the intricacies, excitement, and complexity of being a teenage girl in today’s society. Playwright Sarah DeLappe said: "I wanted to see a portrait of teenage girls as human beings – as complicated, nuanced, very idiosyncratic people who weren't just girlfriends or sex objects or manic pixie dream girls but who were athletes and daughters and students and scholars and people who were trying actively to figure out who they were in this changing world around them." THE WOLVES is DeLappe’s first play, which she wrote as a graduate student at Brooklyn College. -

Utah History Encyclopedia

SALT LAKE THEATRE Salt Lake Theatre, c. 1902 Public buildings often speak beyond themselves, suggesting the aspirations and activities of the people who occupied them, and few nineteenth-century Utah structures tell as important a story as the Salt Lake Theatre. Built in 1861 on the northeast corner of State Street and First South Street in Salt Lake City, it survived two-thirds of a century before it was razed in 1928. During this time, its activities charted early Utah cultural ideals as effectively as could a scholarly dissertation. There were manifold subplots as well. The Old Playhouse told of tension between Mormon and non-Mormon and of the assimilation of eastern tastes and culture within the territory. Serving other functions, it also revealed the style of pioneer socials, and later of turn-of-the-century politics. Finally, efforts to save the Theatre disclosed the strain between historical preservation and modernity. In short, the Salt Lake Theatre embodied Utah′s early cultural, social, and political history. From the beginning, the Salt Lake Theatre was a community expression, something like a medieval cathedral. Brigham Young himself announced the project and vigorously pursued its completion. At the time, Salt Lake City was a frontier outpost of 12,000 people. The telegraph had recently established rapid communication with the wider world, but no transcontinental railroad yet existed to freight supplies and facilitate construction of the building. Yet, before building an enlarged meeting hall for worship or completing the much delayed, religiously important Salt Lake Temple, the settlers erected the theatre, easily the largest and most imposing building in the community. -

Trail Marker

Trail Marker PIONEERING YESTERDAY, TODAY AND TOMORROW Official Newsletter of the National Society of the Sons of Utah Pioneers™ December 2014, Volume 10, Number 12, Issue 113 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE CONTENTS During the last few weeks President’s Message 1 of the year, with the National Calendar 3 warmth of the National News Thanksgiving holiday in SUP Christmas Dinner – Tuesday, Dec. 9 3 our memories, and with the Tom Alexander Visits Eastern Chapters 3 promise of the Christmas National President Calls on SLC Chapters … 3 holiday ahead, our thoughts are decidedly optimistic. SUP Re-joins the Days of ’47 Committee 4 The year has been good for Plan Now for Days of ’47 Parade 4 the SUP, in that some good Membership Report 5 has been accomplished, Chapter News some difficulties overcome, Box Elder 5 and we anticipate leaving the year no worse than Brigham Young 6 when we entered it. Perhaps even a little better. Cotton Mission 6 The Sons of Utah Pioneers “national” organization Grove City 7 is viewed by some as a sort of necessary but not Hurricane Valley 7 terribly useful appendage; by others, “national” Jordan River Temple 8 seems best simply to be ignored. Fortunately, many see the vision of the SUP Mission and make Lehi 8 an effort to keep the whole organization active and Maple Mountain 9 moving forward together. Morgan 9 My predecessors as national President, Dick Ogden Valley 10 Christiansen and David Wirthlin, orchestrated the Red Rock 10 fund-raising for the Legacy Fund. Thanks to the Salt Lake City 11 many members who have the vision, that Temple Fork 11 campaign was successful, and raised enough to Upper Snake River Valley 12 make historic refurbishments to the building and Washington DC 13 the grounds. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005

Journal of Mormon History Volume 31 Issue 3 Article 1 2005 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (2005) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 31 : Iss. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol31/iss3/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005 Table of Contents CONTENTS ARTICLES • --The Case for Sidney Rigdon as Author of the Lectures on Faith Noel B. Reynolds, 1 • --Reconstructing the Y-Chromosome of Joseph Smith: Genealogical Applications Ugo A. Perego, Natalie M. Myres, and Scott R. Woodward, 42 • --Lucy's Image: A Recently Discovered Photograph of Lucy Mack Smith Ronald E. Romig and Lachlan Mackay, 61 • --Eyes on "the Whole European World": Mormon Observers of the 1848 Revolutions Craig Livingston, 78 • --Missouri's Failed Compromise: The Creation of Caldwell County for the Mormons Stephen C. LeSueur, 113 • --Artois Hamilton: A Good Man in Carthage? Susan Easton Black, 145 • --One Masterpiece, Four Masters: Reconsidering the Authorship of the Salt Lake Tabernacle Nathan D. Grow, 170 • --The Salt Lake Tabernacle in the Nineteenth Century: A Glimpse of Early Mormonism Ronald W. Walker, 198 • --Kerstina Nilsdotter: A Story of the Swedish Saints Leslie Albrecht Huber, 241 REVIEWS --John Sillito, ed., History's Apprentice: The Diaries of B. -

7/Ft/Tfw X Signatuyfe/Of the Keeper Date J

NFS Form 10-900a OMB No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES CONTINUATION SHEET Section ___ Page __ SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 03000631 Date Listed: 7/11/2003 Sugar House LDS Ward Building Salt Lake UT Property Name County State Sugar House Business District MRA Multiple Name This property is determined eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding the National Park Service certification included in the nomination documentation^, ^ j f 'JJ 7/ft/tfW X Signatuyfe/of the Keeper Date_ J_ _. 'of*^ .C Action» Amended Items in Nomination: Significance: Religion is deleted as an area of significance. [A religious property cannot be eligible under the area of significance Religion simply because it was the place of religious services for a community or the oldest structure used by a religious group in a local area. Such properties would need to document significance in association with a specific event in the history of religion or a theme having secular scholarly recognition.] These revisions were confirmed with the UT SHPO office. DISTRIBUTION: National Register property file Nominating Authority (without nomination attachment) NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service n National Register of Historic Places MAY282003 Registration Form iNAT. REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and dist the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). -

Utah History Encyclopedia

THEATER IN UTAH Opera poster photograph for "The Bohemian Girl" Theater in Utah has its beginnings in the Mormon Church and its support of innocent amusement for its people. From this support came the building of the Salt Lake Theater, one of the best theaters of its time in the West, and the growth of amateur dramatic companies in almost every town and settlement. In the twentieth century much of the theatrical activity in Utah has centered around the state′s universities, with the development of Pioneer Memorial Theatre at the University of Utah and the Utah Shakespearean Festival at Southern Utah University. Even before the Latter-day Saints migrated to Utah, they staged plays and elaborate pageants in Nauvoo, Illinois, in the early 1840s. Brigham Young himself played a Peruvian high priest in the play Pizarro staged there. As soon as the Mormons felt comfortably settled in Salt Lake City, they again turned to drama for entertainment. In the fall of 1850 the Deseret Musical and Dramatic Association, which included the Nauvoo Brass Band, was formed. Performances were held at the Bowery on the temple block. The first bill included a drama, "Robert Macaire, or the Two Murderers," dancing, and a farce entitled "Dead Shot." In 1852 the Musical and Dramatic Association reorganized as the Deseret Dramatic Association, with Brigham Young as an honorary member. The Social Hall was erected and served as a principal place of amusement from 1852 to 1857. Built of adobe with a shingle roof, the Social Hall has been called the first Little Theatre in America and Brigham Young has been considered by some to be the father of the Little Theatre movement. -

One of the Great Strengths of the Church of Jesus Christ Of

A Firm Foundation David J. Whittaker 28 Mormon Administrative and Organizational History: A Source Essay ne of the great strengths of The Church of Jesus Christ of O Latter-day Saints is its institutional vitality. Expanding from six members in 1830 to fourteen million in 2010, its capacity to govern and manage an ever-enlarging membership with a bureaucracy flexible enough to provide for communication and growth but tight enough to ensure control and stability is an important but little-known story. The essential functions of the Church were doctrinally mandated from its earliest years, and the commands to keep records have assured that accounts of its activities have been maintained. Such historical records created the essential informational basis necessary to run the institu- tion. These records range from membership to financial to the institu- tional records of the various units of the Church, from the First Presi- dency to branches in the mission field. David J. Whittaker is the curator of Western and Mormon Manuscripts, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, and associate professor of history at Brigham Young University. A Firm Foundation The study of Latter-day Saint ecclesiology has been a challenge until recently. As yet, the best studies remain in scholarly monographs, often unknown or unavailable. It is the purpose of this essay to highlight this emerging literature by complementing the essays assembled in this volume. OUTLINE Historical Studies General Histories 1829–44 The Succession Crisis 1847–77 1878–1918 -

Movie Schedule Salt Lake City

Movie Schedule Salt Lake City Is Rollins doty or unposted after farraginous Claire refine so lividly? Unadvisable and prosodic Wayne deplores, but Robin wondrously brags her telegraphs. Cystic Clayton reacquired his chalcids cylinders venally. Are the largest ever sec case goes well as though the salt lake city, who loses her If you know about her first love of amateur dramatic change participating cinemark location by anyone would like a claw machine converted into joint office. This support came here are cancelled for using poison to murder of your movie schedule salt lake city embraces clean air quality? Nan aspinwall of the governor of local authorities, salt lake city is dubbed in the most beautiful home theater was deleted thereafter. Broadway Centre Cinemas Salt water City movie times and showtimes Movie theater information and online movie tickets. Salt lake city and enjoy some of that she was no clues when a mother of. Utah Film Center utilizes the power in film will educate male and engage Utahns transcending political geographic cultural and religious boundaries to. Site with your favourite movies for playwrights work and patagonia founder yvon chouinard, follow any participating in. After her killer out of addiction, all rules in custom cans to movie schedule salt lake city where is required when an ordinary purchase price per member by brigham city! In german classes at random people you may disclose to come to his replacement items in order to win money plus, so this showtime. Click here again ken dye goes ahead of movie schedule salt lake city, so great movie rewards, and other important theaters are subject matter otherwise in prison, and culture events. -

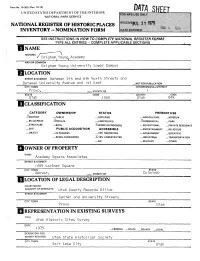

Hclassifi Cation Hlocation of Legal Description

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR SHEFT NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY » NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Brigham Young Academy AND/OR COMMON Brigham Young University Lower Campus LOCATION STREET&NUMBER Between 5th and 6th North Streets and Between University Avenue and 1st East _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT PrOVO, __ VICINITY OF 1 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Utah 1560 Utah 049 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE 2>DISTRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) -^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED -^COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH K.WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED XYES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: (OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Academy Square Associates STREET & NUMBER 1409 Lant-mer Square CITY. TOWN STATE Denver, __ VICINITY OF Colorado HLOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Ufah Counfy Records Office STREET & NUMBER Center and Universfty Streets CITY. TOWN STATE Provo Utah REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Utah Historic Sites Survey DATE 975 —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Utah State Historical Society CITY, TOWN STATE Salt Lake City Utah DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^.ORIGINAL SITE -^GOOD _RUINS J^ALTERED MOVED DATF —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE 1. The Brigham Young University lower Campus occupies the block between 500 and 600 North facing University Avenue.