Disability in Comics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Charismatic Leadership and Cultural Legacy of Stan Lee

REINVENTING THE AMERICAN SUPERHERO: THE CHARISMATIC LEADERSHIP AND CULTURAL LEGACY OF STAN LEE Hazel Homer-Wambeam Junior Individual Documentary Process Paper: 499 Words !1 “A different house of worship A different color skin A piece of land that’s coveted And the drums of war begin.” -Stan Lee, 1970 THESIS As the comic book industry was collapsing during the 1950s and 60s, Stan Lee utilized his charismatic leadership style to reinvent and revive the superhero phenomenon. By leading the industry into the “Marvel Age,” Lee has left a multilayered legacy. Examples of this include raising awareness of social issues, shaping contemporary pop-culture, teaching literacy, giving people hope and self-confidence in the face of adversity, and leaving behind a multibillion dollar industry that employs thousands of people. TOPIC I was inspired to learn about Stan Lee after watching my first Marvel movie last spring. I was never interested in superheroes before this project, but now I have become an expert on the history of Marvel and have a new found love for the genre. Stan Lee’s entire personal collection is archived at the University of Wyoming American Heritage Center in my hometown. It contains 196 boxes of interviews, correspondence, original manuscripts, photos and comics from the 1920s to today. This was an amazing opportunity to obtain primary resources. !2 RESEARCH My most important primary resource was the phone interview I conducted with Stan Lee himself, now 92 years old. It was a rare opportunity that few people have had, and quite an honor! I use clips of Lee’s answers in my documentary. -

Orientalism Within the Creation and Presentation of Doctor Strange

Sino-US English Teaching, May 2021, Vol. 18, No. 5, 131-135 doi:10.17265/1539-8072/2021.05.007 D DAVID PUBLISHING Orientalism Within the Creation and Presentation of Doctor Strange XU Hai-hua University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, Shanghai, China Doctor Strange has become a representation of superheroes with magic in the world of Marvel. Considering his identity as Sorcerer Supreme, there is a crucial connection between the Orient and his magic. The paper will discuss the detailed symbols of Orientalism in the process of creation and presentation of Doctor Strange respectively to figure out the change of Orientalism with the times within the texts of Doctor Strange and its existence today. Keywords: Orientalism, Doctor Strange, magic in the world of Marvel Introduction Ever since his debut in 1963, Doctor Strange has become a representation of superheroes with magic in the world of Marvel. Noticeably, a number of eastern elements have never ceased to appear in the Doctor Strange series throughout the times. Several characters are from the east, and the mysterious Asian land is also the birthplace of Doctor Strange’s magic power. Considering his identity as Sorcerer Supreme, the first and strongest sorcerer in Marvel, there must be a crucial connection between the Orient and his magic, both in the entire Marvel world, and in traditional western culture. Eastern elements under the account of westerners can be well interpreted with reference to the general concept of Orientalism. Thus, this paper aims to discuss the way the idea of Orientalism evolves with the times that is showcased within the texts of Doctor Strange. -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

Doctor Strange Comics As Post-Fantasy

Evolving a Genre: Doctor Strange Comics as Post-Fantasy Jessie L. Rogers Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Karen Swenson, Chair Nancy A. Metz Katrina M. Powell April 15, 2019 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Fantasy, Comics Studies, Postmodernism, Post-Fantasy Copyright 2019, Jessie L. Rogers Evolving a Genre: Doctor Strange Comics as Post-Fantasy Jessie L. Rogers (ABSTRACT) This thesis demonstrates that Doctor Strange comics incorporate established tropes of the fantastic canon while also incorporating postmodern techniques that modernize the genre. Strange’s debut series, Strange Tales, begins this development of stylistic changes, but it still relies heavily on standard uses of the fantastic. The 2015 series, Doctor Strange, builds on the evolution of the fantastic apparent in its predecessor while evidencing an even stronger presence of the postmodern. Such use of postmodern strategies disrupts the suspension of disbelief on which popular fantasy often relies. To show this disruption and its effects, this thesis examines Strange Tales and Doctor Strange (2015) as they relate to the fantastic cornerstones of Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings and Rowling’s Harry Potter series. It begins by defining the genre of fantasy and the tenets of postmodernism, then it combines these definitions to explain the new genre of postmodern fantasy, or post-fantasy, which Doctor Strange comics develop. To show how these comics evolve the fantasy genre through applications of postmodernism, this thesis examines their use of otherworldliness and supernaturalism, as well as their characterization and narrative strategies, examining how these facets subvert our expectations of fantasy texts. -

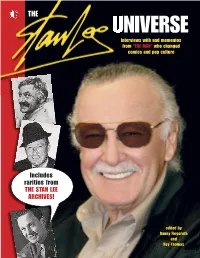

Includes Rarities from the STAN LEE ARCHIVES!

THE UNIVERSE Interviews with and mementos from “THE MAN” who changed comics and pop culture Includes rarities from THE STAN LEE ARCHIVES! edited by Danny Fingeroth and Roy Thomas CONTENTS About the material that makes up THE STAN LEE UNIVERSE Some of this book’s contents originally appeared in TwoMorrows’ Write Now! #18 and Alter Ego #74, as well as various other sources. This material has been redesigned and much of it is accompanied by different illustrations than when it first appeared. Some material is from Roy Thomas’s personal archives. Some was created especially for this book. Approximately one-third of the material in the SLU was found by Danny Fingeroth in June 2010 at the Stan Lee Collection (aka “ The Stan Lee Archives ”) of the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, and is material that has rarely, if ever, been seen by the general public. The transcriptions—done especially for this book—of audiotapes of 1960s radio programs featuring Stan with other notable personalities, should be of special interest to fans and scholars alike. INTRODUCTION A COMEBACK FOR COMIC BOOKS by Danny Fingeroth and Roy Thomas, editors ..................................5 1966 MidWest Magazine article by Roger Ebert ............71 CUB SCOUTS STRIP RATES EAGLE AWARD LEGEND MEETS LEGEND 1957 interview with Stan Lee and Joe Maneely, Stan interviewed in 1969 by Jud Hurd of from Editor & Publisher magazine, by James L. Collings ................7 Cartoonist PROfiles magazine ............................................................77 -

Sacks Checchetto Mossa

8 MARVEL.COM $3.99 ADVISORY PARENTAL 0 0 8 1 1 US MOSSA CHECCHETTO SACKS 7 5 9 6 0 6 0 8 8 3 6 2 FORTY-FIVE YEARS AGO, THE WORLD’S SUPER VILLAINS ORGANIZED UNDER THE RED SKULL AND COLLECTIVELY WIPED OUT NEARLY ALL OF THE SUPER HEROES. FEW SURVIVED THE CARNAGE THAT FATEFUL DAY, AND NONE OF THEM UNSCATHED. THE UNITED STATES WAS DIVIDED UP INTO TERRITORIES CONTROLLED BY THE VILLAINS, AND THE GOOD PEOPLE SURVIVE IN THESE WASTELANDS AS BEST THEY CAN. AMONG THEM LIVES A FORMER HERO WHO’S GIVEN UP ON THAT WAY OF LIFE. HE IS CLINT BARTON, BUT SOME KNOW HIM AS… AN EYE FOR AN EYE PART 8 SLINGS AND ARROWS CLINT BARTON IS GOING BLIND. HE WANTS TO SEE THROUGH ONE FINAL MISSION—EXACTING REVENGE ON HIS FORMER THUNDERBOLTS COLLEAGUES THAT HELPED BRING ABOUT THE DEATHS OF THE AVENGERS—BEFORE HE LOSES HIS SIGHT FOR GOOD. HE’S TAKEN OUT ATLAS AND THE BEETLE, AND AFTER SUFFERING AN INJURY, TURNED TO FORMER CO-HAWKEYE KATE BISHOP TO HELP HIM COMPLETE HIS QUEST. AFTER REGALING HER WITH THE GORY DETAILS OF THE MASSACRE, SHE RELUCTANTLY AGREED TO HELP HER FORMER MENTOR. MEANWHILE, THE MARSHAL BULLSEYE CLOSES IN HAWKEYE, DESPERATE TO FACE A LIVING SUPER HERO ONE MORE TIME… WRITER... ETHAN SACKS ARTIST... MARCO CHECCHETTO COLORIST... ANDRES MOSSA LETTERER... VC’s JOE CARAMAGNA COVER ARTIST... MARCO CHECCHETTO LOGO DESIGN... ADAM DEL RE GRAPHIC DESIGN... ANTHONY GAMBINO EDITOR... MARK BASSO EDITOR IN CHIEF... C.B. CEBULSKI CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER... JOE QUESADA PRESIDENT.. -

Hawkeye, Volume 1 by Matt Fraction (Writer) , David Aja (Artist)

Read and Download Ebook Hawkeye, Volume 1... Hawkeye, Volume 1 Matt Fraction (Writer) , David Aja (Artist) , Javier Pulido (Artist) , Francesco Francavilla (Artist) , Steve Lieber (Artist) , Jesse Hamm (Artist) , Annie Wu (Artist) , Alan Davis (Penciler) , more… Mark Farmer (Inker) , Matt Hollingsworth (Colourist) , Paul Mounts (Colourist) , Chris Eliopoulos (Letterer) , Cory Petit (Letterer) …less PDF File: Hawkeye, Volume 1... 1 Read and Download Ebook Hawkeye, Volume 1... Hawkeye, Volume 1 Matt Fraction (Writer) , David Aja (Artist) , Javier Pulido (Artist) , Francesco Francavilla (Artist) , Steve Lieber (Artist) , Jesse Hamm (Artist) , Annie Wu (Artist) , Alan Davis (Penciler) , more… Mark Farmer (Inker) , Matt Hollingsworth (Colourist) , Paul Mounts (Colourist) , Chris Eliopoulos (Letterer) , Cory Petit (Letterer) …less Hawkeye, Volume 1 Matt Fraction (Writer) , David Aja (Artist) , Javier Pulido (Artist) , Francesco Francavilla (Artist) , Steve Lieber (Artist) , Jesse Hamm (Artist) , Annie Wu (Artist) , Alan Davis (Penciler) , more… Mark Farmer (Inker) , Matt Hollingsworth (Colourist) , Paul Mounts (Colourist) , Chris Eliopoulos (Letterer) , Cory Petit (Letterer) …less Clint Barton, Hawkeye: Archer. Avenger. Terrible at relationships. Kate Bishop, Hawkeye: Adventurer. Young Avenger. Great at parties. Matt Fraction, David Aja and an incredible roster of artistic talent hit the bull's eye with your new favorite book, pitting Hawkguy and Katie-Kate - not to mention the crime-solving Pizza Dog - against all the mob bosses, superstorms -

|||GET||| Little Hits Little Hits (Marvel Now) 1St Edition

LITTLE HITS LITTLE HITS (MARVEL NOW) 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Matt Fraction | 9780785165637 | | | | | Little Hits by Matt Fraction (2013, Trade Paperback) Published by George G. Upon receiving it I was very happy to see that it was beyond my expectations. Believe the hype. Los Angeles Times. Doctor Spectrum Defenders of Dynatron City They were all pretty fun and hilarious, but nothing exactly to gush about. Doctor Doom and the Masters of Evil Foxing to endpapers. Death of the Inhumans Marvel. The Clint and Grills thread was touching and Kate's side of things painted New Jersey in a favorable light for once. Bullet Review: This was just so much fun and so clever. I've decided that I wanted this hardcover for my library but I did not hesitate in getting this trade paperback just so I could read issue It's told thru a lot of iconography and blurred dialogue. Thanos I've read the first volume couple of days ago, and while it was very entertaining with a distinctly different way of presenting Now THIS is why writer Matt Fraction is a genius, and this series is one of the most critically acclaimed Marvel comics in the last years! As the name of this collection says, it is a trade of one-offs and short arcs. Alassaid : an agent of the Communist interThe squadred is now slated to apartment by putting itching lead in the Big Ten Closing Thoughts: Another futzing volume down already? Even if you read it before, bro. Defenders Marvel. It's a fun story, slightly let down by the artwork. -

MEET the MIGHTY AVENGERS! 6 Get the Inside Story on Earth’S Mightiest Heroes! 4

MEET THE MIGHTY AVENGERS! 6 Get the inside story on Earth’s Mightiest Heroes! 4 1 Black Widow™ - Natasha Romanoff lives up to her moniker, the Black Widow, as an international spy for S.H.I.E.L.D. Clever and resourceful, Romanoff doesn’t have super powers, but she can talk or kick her way out of any tricky situation. 2 Captain America™ - An ordinary man who wanted to fight for his country, Steve Rogers was transformed by a special serum into the ultimate soldier, Captain America. With super strength and agility, along with the mind of a great strategist and leader, Captain 1 3 America is the unifying force behind the Avengers team. 3 Hawkeye™ - Clint Barton, the ace archer also known as Hawkeye, never misses his mark. he now works as a spy for S.H.I.E.L.D., when he’s not saving the world with the Avengers, of course. 4 Iron Man™ - Tony Stark is wise-cracking billionaire and the brains behind the powerful Stark Industries. Stark invented the Iron Man suit, which allows him to fly, fire weapons, and protect and help people all around the world. 5 The Hulk™ - Bruce Banner was a brilliant scientist studying Gamma radiation when an accident caused him to develop the super strong and super green alter ego, the Hulk. When transformed, the Hulk may be hard to control but he’s nearly 5 invincible, making him an essential part of the Avengers team. 6 Thor™ - Prince of the otherworldly realm of Asgard, Thor has extraordinary powers of strength and the ability to summon lightning with his hammer, Mjolnir. -

Hulk Smash! September, 2020, Vol

Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture Hulk Smash! September, 2020, Vol. 20 (Issue 1): pp. 28 - 42 Clevenger and Acquaviva Copyright © 2020 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture All rights reserved. ISSN: 1070-8286 Hulk Smash! Violence in The Incredible Hulk Comics Shelly Clevenger Sam Houston State University & Brittany L. Acquaviva Sam Houston State University 28 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture Hulk Smash! September, 2020, Vol. 20 (Issue 1): pp. 28 - 42 Clevenger and Acquaviva Abstract “Hulk smash!” is one of the most iconic phrases uttered in the pages of comic books. The Incredible Hulk is one of comics’ most violent characters as the Hulk smashes first and asks questions later. The popularity of the comic book genre has exploded within past decades and the interest in comics has increased. But exactly how violent is The Incredible Hulk and what does that mean for readers? This research examines the occurrence of violence in the Incredible Hulk comics through a thematic content analysis of 248 issues. Specifically, such themes as violence against men and women, unpunished violence, formal punishments of violence, interventions to stop violence and the justification provided for violence were assessed. The goal of the research was to determine the amount and level of violence within the comic and in what context it occurred. Results indicate that there is a large amount of violence occurring within the pages of the Incredible Hulk, but that this violence is often justified and committed by the Hulk to protect himself and others. A discussion is provided regarding the potential impact this may have on a reader and their view of violence, crime and justice. -

The Incredible Hulk

The Incredible Hulk Monster, Man, Hero Dana McKnight Texas Christian University hen Marvel Comics introduced The Incredible Hulk in 1962, the following question was displayed prominently within a bold yellow question mark on W the front page: “Is he man or monster or…is he both?”1 Today, it seems easy to dismiss questions about the Incredible Hulk being a monster by merit of the popular Marvel Universe films, which brought the Incredible Hulk to a wide audience. I suspect that most Americans recognize the Incredible Hulk as a member of the Avengers: a hero, not a monster. However, when the Incredible Hulk first made his debut, Stan Lee expected his readers to wonder whether or not the Hulk would be a villain or a hero.2 Drawing from the first six issues of The Incredible Hulk I will discuss how the Incredible Hulk is simultaneously a hero and a monster, both an allegory of the military might of the United States in the atomic age and of the tenuous relationship between security and safety manifest in the uncontrolled destructive power of nuclear weapons. I will close with a glimpse into the contemporary post-9/11 Hulk. Man or Monster? First, it is cogent to get back to the “man or monster” question posed by Stan Lee in the very first issue of The Incredible Hulk, because the Hulk was both a man, Bruce Banner, and a monster, the Hulk. The “man-or-monster” question is not new and was 1 Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, “The Coming of the Hulk,” The Incredible Hulk, no. -

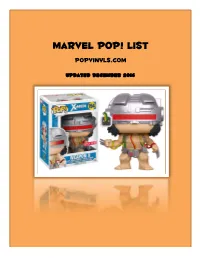

Marvel Pop! List Popvinyls.Com

Marvel Pop! List PopVinyls.com Updated December 2016 01 Thor 23 IM3 Iron Man 02 Loki 24 IM3 War Machine 03 Spider-man 25 IM3 Iron Patriot 03 B&W Spider-man (Fugitive) 25 Metallic IM3 Iron Patriot (HT) 03 Metallic Spider-man (SDCC ’11) 26 IM3 Deep Space Suit 03 Red/Black Spider-man (HT) 27 Phoenix (ECCC 13) 04 Iron Man 28 Logan 04 Blue Stealth Iron Man (R.I.CC 14) 29 Unmasked Deadpool (PX) 05 Wolverine 29 Unmasked XForce Deadpool (PX) 05 B&W Wolverine (Fugitive) 30 White Phoenix (Conquest Comics) 05 Classic Brown Wolverine (Zapp) 30 GITD White Phoenix (Conquest Comics) 05 XForce Wolverine (HT) 31 Red Hulk 06 Captain America 31 Metallic Red Hulk (SDCC 13) 06 B&W Captain America (Gemini) 32 Tony Stark (SDCC 13) 06 Metallic Captain America (SDCC ’11) 33 James Rhodes (SDCC 13) 06 Unmasked Captain America (Comikaze) 34 Peter Parker (Comikaze) 06 Metallic Unmasked Capt. America (PC) 35 Dark World Thor 07 Red Skull 35 B&W Dark World Thor (Gemini) 08 The Hulk 36 Dark World Loki 09 The Thing (Blue Eyes) 36 B&W Dark World Loki (Fugitive) 09 The Thing (Black Eyes) 36 Helmeted Loki 09 B&W Thing (Gemini) 36 B&W Helmeted Loki (HT) 09 Metallic The Thing (SDCC 11) 36 Frost Giant Loki (Fugitive/SDCC 14) 10 Captain America <Avengers> 36 GITD Frost Giant Loki (FT/SDCC 14) 11 Iron Man <Avengers> 37 Dark Elf 12 Thor <Avengers> 38 Helmeted Thor (HT) 13 The Hulk <Avengers> 39 Compound Hulk (Toy Anxiety) 14 Nick Fury <Avengers> 39 Metallic Compound Hulk (Toy Anxiety) 15 Amazing Spider-man 40 Unmasked Wolverine (Toytasktik) 15 GITD Spider-man (Gemini) 40 GITD Unmasked Wolverine (Toytastik) 15 GITD Spider-man (Japan Exc) 41 CA2 Captain America 15 Metallic Spider-man (SDCC 12) 41 CA2 B&W Captain America (BN) 16 Gold Helmet Loki (SDCC 12) 41 CA2 GITD Captain America (HT) 17 Dr.