Exmouth and Torquay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Devon , but There Is a General Idea That It May Be Said to Be Within a Line from Teignmouth to Modbury, Spreading Inward in an Irregular Sort of Way

SO UT H D EVO N PAI NTED BY E H ANNAF O RD C . D ESC R IBED BY C H AS R R WE M . I . O , J . WI TH 2 4 F U LL- PAG E I LLU STRATI O NS I N C O LO U R L O N D O N ADAM AND CH ARLES BLACK 1 907 C ONTENTS I NTRO DU C TO RY TO R"UAY AND TO R B AY DARTMO U T H TEIGNMO U 'I‘ H N EWTO N A B B O T ToTNEs K INGSB RI D GE I ND E" LIST O F ILLU STRATIONS 1 S . Fore treet, Totnes F ACING 2 C . A Devonshire ottage 3 . Torquay 4 B abbacombe . , Torquay An i 5 . st s Cove , Torquay 6 C C . ompton astle 7 . Paignton 8 . Brixham Butterwalk 9 . The , Dartmouth 1 ’ 0. C Bayard s ove , Dartmouth 1 1 S . Fosse treet, Dartmouth 1 2 . Dittisham , on the Dart 1 3 . rt Kingswear, Da mouth 1 4 Shaldon , Teign mouth from 1 5 . Teignmouth and The Ness 1 6 . Dawlish 1 St ’ 7 . Leonard s Tower, Newton Abbot LI ST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Bradley Woods, Newton Abbot Berry Pomeroy Castle Salcombe Kingsbridge Salcombe Castle S Bolt Head, alcombe Brent S O U T H D E V O N INTRODU C TORY PER HAPS there is no rigorously defined region in cluded under the title of South Devon , but there is a general idea that it may be said to be within a line from Teignmouth to Modbury, spreading inward in an irregular sort of way . -

Teignmouth Economic and Data Profile Indices of Deprivation

Teignmouth economic and data profile Included in this profile are recently published datasets, where these are provided for Teignmouth, or for Teignbridge where this is relevant and recent. Additional data may be available from [email protected] upon request to support business cases, where the objective of the case, or bid and bid selection criteria are provided. Indices of deprivation These are reviewed once every four years. Data is provided at the Lower Level Super Output Area (LSOA) which are neighbourhoods of around 1,500-2,000 people. There are 32,844 LSOAs in England and each one is ranked against each other to provide a relative overall position nationally for each neighbourhood. A score of 100% is the least deprived in England and a score of 0% is the most deprived. The index is provided as an overall composite measure of deprivation but is made up of a number of sub-domains, for example income, which are also published alongside the overall index. Often if bidding for national funding pots where deprivation is a factor considered as part of the scoring criteria, the criteria will ask whether the proposed project is in an LSOA that is in the worst 10%/20%/25% in England. Sometimes it can also be helpful even if the project is not within a most deprived LSOA, but is within a mile, or so of them and serves people who live within the most deprived areas to articulate this in the bid. Separately the income and skills domains from the indices of deprivation showing better performing areas can be useful as a proxy of high, or improving levels of income, or skills to articulate to businesses wishing to invest in Teignmouth of the potential market or workforce available. -

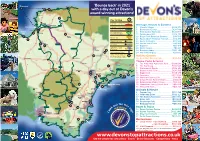

View Our Brochure

Lundy Island i Lynmouth Be inspired for a fabulous 5 SWCP Lynton 5 6 A39 A399 Combe Martin A39 day out at Devon’s award Lee i Ilfracombe Mortehoe winning attractions Woolacombe A3123 A361 7 A39 Croyde Key to Map Saunton Braunton A399 Major roads - A classification A361 Heritage, Houses & Gardens SWCP i Barnstaple Tarka Trail 1 Clovelly Village ....................................EX39 5TA River Taw Estuary SWCP Major roads - B classification Instow 3 Dartington Crystal ............................EX38 7AN A361 Long Distance Footpath Westward Ho 5 A39 11 Killerton House ......................................EX5 3LE Hartland Areas of Outstanding 14 Seaton Jurassic ................................ EX12 2WD SWCP Point 4 i Bideford 8 2 MOORS WAY Natural Beauty (AONB) Clovelly 17 Bicton Park Botanical Gardens .........EX9 7BG Hartland 1 i South Molton National Parks 21 Royal Albert Memorial Museum ....... EX4 3LS A377 A39 2 22 Exeter Cathedral ...................... ............EX1 1HS Villages / small towns Mortehoe 23 Castle Drogo ..........................................EX6 6PB A388 3 i Great Torrington Tarka rail link Area centres Braunton 26 Bygones ................................................. TQ1 4PR Larger towns, showing 28 Kents Cavern ..........................................TQ1 2JF 2 MOORS WAY approximate extent of Tarka Trail Barnstaple 33 Buckfast Abbey ...................................TQ11 0EE A386 A3124 built up area. i Tiverton Tourist Information Centres i 35 Morwellham Quay ...............................PL19 8JL A388 A377 10 A303 Tourist Attraction (colour shows Activity Centres 9 Cullompton type of attraction. See Key to 0 A3072 Devon’s Top Attractions above). 34 River Dart Country Park ..................TQ13 7NP Morchard Bishop i A373 Holsworthy Hatherleigh A30 A3072 Theme Parks & Farms A3072 A377 A396 2 The Milky Way Adventure Park ....*EX39 5RY A3072 i Crediton A386 A388 11 i A35 Axminster 4 The Big Sheep ................................... -

Evaluation of the Use of Working with Others - Building Trust

Evaluation of the use of Working with Others - Building Trust For the Shaldon Flood Risk Project Ed Straw and Lindsey Colbourne March 2009 Lindsey Colbourne Associates Index Index ............................................................................................ 2 1 This report, the brief and approach .......................................... 5 1.1 Introduction to this report ........................................................................... 5 1.2 The approach............................................................................................. 6 2 Executive summary .................................................................. 8 2.1 The highest engagement benefit: cost ratio is not achieved by deciding whether to engage or not, but by making the right decision about how much to engage. ........ 8 2.2 Critical to a high engagement benefit: cost ratio is doing engagement well, and doing it efficiently. ........................................................................................... 10 2.3 What next? The pilot work at Shaldon raises a strategic set of issues to be resolved: ........................................................................................................ 10 3 Using the BTwC approach in Shaldon – what was done, what happened 11 3.1 Origins .................................................................................................... 11 3.2 What was done, and how the BTwC approach differed from „business as usual‟ 13 3.2.1 Timing and extent of BTwC activities ................................................... -

Soils of North Wyke and Rowden

THE SOILS OF NORTH WYKE AND ROWDEN By T.R.Harrod and D.V.Hogan (2008) Revised edition of original report by T.R. Harrod, Soil Survey of England and Wales (1981) CONTENTS Preface 1. Introduction 1.1 Situation, relief and drainage 1.2 Geology 1.3 Climate 1.3.1 Rainfall 1.3.2 Temperature 1.3.3 Sunshine 2. The Soils 2.1 Methods of survey and classification 2.2 Denbigh map unit 2.3 Halstow map unit 2.4 Hallsworth map unit 2.5 Teign map unit 2.6 Blithe map unit 2.7 Fladbury map unit 2.8 Water retention characteristics 3. Soils and land use 3.1 Soil suitability for grassland 3.2 Soil suitability for slurry acceptance 3.3 Ease of cultivation 3.4 Soil suitability for direct drilling 3.5 Soils and land drainage 4. Soil capacities and limitations 4.1 Explanation 4.2 Hydrology of Soil Types (HOST) 4.3 Ground movement potential 4.4 Flood vulnerability 4.5 Risk of corrosion to ferrous iron 4.6 Pesticide leaching risk 4.7 Pesticide runoff risk 4.8 Hydrogeological rock type 4.9 Groundwater Protection Policy (GWPP) leaching 5 National context of soils occurring at North Wyke and Rowden 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Halstow association (421b) 5.3 Crediton association (541e) 5.4 Denbigh 1 association (541j) 5.5 Alun association (561c) 5.6 Hallsworth 1 association (712d) 5.7 Fladbury 1 association (8.13b) Figures 1 Mean annual rainfall (mm) at North Wyke (2001-2007) 2 Mean annual temperatures (0C) at North Wyke (2001-2007) 3 Mean monthly hours of bright sunshine at North Wyke (2001-2007) 4 Soil map of North Wyke and Rowden 5a Water retention characteristics of the -

Devon Redlands Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 148: Devon Redlands Area profile: Supporting documents www.naturalengland.org.uk 1 National Character 148: Devon Redlands Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment White Paper1, Biodiversity 20202 and the European Landscape Convention3, we are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas (NCAs). These are areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision-making framework for the natural environment. NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform theirdecision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The informationthey contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a landscape scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage broader partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will also help to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental Opportunity (SEOs) are suggested, which draw on this integrated information. The SEOs offer guidance on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. 1 The Natural Choice: Securing the Value of Nature, Defra NCA profiles are working documents which draw on current evidence and (2011; URL: www.official-documents.gov.uk/document/cm80/8082/8082.pdf) 2 knowledge. -

Local Resident Submissions to the Devon County Council Electoral Review

Local resident submissions to the Devon County Council electoral review This PDF document contains submissions from local residents M-Z Some versions of Adobe allow the viewer to move quickly between bookmarks. Local Boundary Commission for England Consultation Portal Page 1 of 1 Devon County Personal Details: Name: Patricia Wendy Machin E-mail: Postcode: Organisation Name: Bishopsteignton Residents Association Comment text: I have been a resident of Bishopsteignton for 17'years and am a member of the local residents association. I feel very strongly that it would not be in the best interests of this village to exclude it from the area of Teignmouth, as this is where most people go for shopping and services. The boundary of the A 380 and the extensive building there recently makes it difficult to get into Kingsteignton, whereas Teignmouth adjoins our village and is very accessible. The boundary between the two is not well marked and we identify with and share facilities and activities very much with Teignmouth and Shaldon. Our recent village festival was well attended by Teignmouth Residents and many people here are involved in organisations there, especially sailing and rowing, local churches and choirs, political groups and the arts. We feel very much a coastal area and our identity is here. We have a very active and strong local identity which includes Teignmouth and is highly valued by the people who live and visit here. Please do not change that, for the sake of political expediency. If democracy and local participation in the governance of this area means anything, I hope and trust that you will listen and take account of the views of the residents of Bishopsteignton. -

1911-Census-Transcription

Comp Yrs Age next Marriage of Address Name Relationship Gender b'day State Marr Children Occupation Born Nationality Still Alive Alive Dead Wear Farm Stooke Charles Head Male 43 Married Farmer Teignmouth British Wear Farm Stooke Laura Frances Wife Female 38 Married 13 3 3 0 Birmingham Wear Farm Stooke Frances Mary Daughter Female 12 Single Bishopsteignton Wear Farm Stooke Edward Arthur Son Male 10 Single Bishopsteignton Wear Farm Stooke Winifred Daughter Female 8 Single Bishopsteignton Wear Farm Hannaford Winifred Governess Female 19 Single Governess Rattery General Wear Farm Emmett Maud Servant Female 21 Single domestic Kingsteignton Ware Cottage Shapter William Head Male 50 Married Farm - Shepherd Kenn Ware Cottage Shapter Bessie Wife Female 48 Married 26 3 3 0 Liverton Ware Cottage Shapter William John Son Male 23 Single Farm - Carter Paignton Railway - Ware Cottage Shapter John Henry Son Male 21 Single Labourer Paignton Ware Cottage Shapter Beatrice Maud Daughter Female 18 Single Highweek Gunn Cottages Walling William Henry Head Male 39 Married Farm - Labourer Hennock Gunn Cottages Walling Ada Wife Female 34 Married 8 4 4 0 Broadhempston Gunn Cottages Walling Ida Daughter Female 7 Single School Newton Abbot Gunn Cottages Walling George Son Male 5 Single School Newton Abbot Gunn Cottages Walling Morrison Son Male 3 Single Bishopsteignton Gunn Cottages Walling Eliza Daughter Female 1 Single Bishopsteignton Mason - Gunn Cottages Walling John Boarder Male 39 Single Labourer Bovey Tracey Gunn Cottages Bowden William Head Male 43 Married -

South Devon and Dorset Coastal Aaadvisoryadvisory Group (SDADCAG)

South Devon and Dorset Coastal AAAdvisoryAdvisory Group (SDADCAG) Shoreline Management Plan Review (SMP2) Durlston Head to Rame Head Shoreline Management Plan (Final) June 2011 Durlston Head to Rame Head SMP2 Shoreline Management Plan Page deliberately left blank for doubledouble----sidedsided printing Durlston Head to Rame Head SMP2 Shoreline Management Plan Contents Amendment Record This report has been issued and amended as follows: Issue Revision Description Date Approved by 1 0 Draft – for Public Consultation 14/04/2009 HJ 2 0 Draft – working version for CSG 11/12/2009 JR 3 0 Draft Final – re-issued to NQRG 17/08/2010 JR 4 0 Final 06/01/2011 JR Halcrow Group Limited Ash House, Falcon Road, Sowton, Exeter, Devon EX2 7LB Tel +44 (0)1392 444252 Fax +44 (0)1392 444301 www.halcrow.com Halcrow Group Limited has prepared this report in accordance with the instructions of their client, South Devon and Dorset Coastal Advisory Group, for their sole and specific use. Any other persons who use any information contained herein do so at their own risk. © Halcrow Group Limited 2011 Durlston Head to Rame Head SMP2 Shoreline Management Plan Page deliberately left blank for doubledouble----sidedsided printing Durlston Head to Rame Head SMP2 Shoreline Management Plan Table of CCContentsContents 111 INTRODUCTIONINTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ............................................................................................... -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for South and East Devon Habitat Regulations Executive Committee, 14/07/2020 14:00

Public Document Pack East Devon District Council Blackdown House Border Road Heathpark Industrial Estate Honiton EX14 1EJ DX 48808 HONITON Tel: 01404 515616 Agenda for South and East Devon Habitat Regulationswww.eastdevon.gov.uk Executive Committee Tuesday, 14th July, 2020, 2.00 pm Members of South and East Devon Habitat Regulations Executive Committee Councillors R Sutton, M Wrigley, and D Ledger Venue: On line via the Zoom App. All Councillors and registered speakers will have been sent an appointment with the meeting link. Contact: Chris Lane 01395 517544; email [email protected] (or group number 01395 517546) 6 July 2020 1 Public speaking Information on public speaking is available online. 2 Minutes of the previous meeting (Pages 3 - 6) 3 Apologies 4 Declarations of interest Guidance is available online to Councillors and co-opted members on making declarations of interest 5 Matters of urgency Information on matters of urgency is available online 6 Confidential/exempt items page 1 To agree any items to be dealt with after the public (including the Press) have been excluded. There are no items which officers recommend should be dealt with in this way. 7 2019-20 Annual Business Plan (Pages 7 - 47) 8 Financial Report July 2020 (Pages 48 - 57) 9 Risk Register Report 2020 (Pages 58 - 71) 10 2020-21 Annual Business Plan (Pages 72 - 95) 11 Dawlish SANGS Refreshments (Pages 96 - 101) Under the Openness of Local Government Bodies Regulations 2014, any members of the public are now allowed to take photographs, film and audio record the proceedings and report on all public meetings (including on social media). -

View Our Location

Lundy Island i Lynmouth ‘Bounce back’ in 2021 6 SWCP Lynton 6 7 A39 A399 Combe Martin A39 with a day out at Devon’s Lee i Ilfracombe Mortehoe award winning attractions! Woolacombe A3123 A361 8 A39 Croyde Key to Map Saunton Braunton A399 Major roads - A classification A361 SWCP i Barnstaple Tarka Trail Heritage, Houses & Gardens River Taw Estuary SWCP Major roads - B classification Instow 1 Clovelly Village ....................................EX39 5TA A361 Long Distance Footpath Westward Ho 6 A39 3 Dartington Crystal ..............................EX38 7AN Hartland Areas of Outstanding 4 RHS Garden Rosemoor ...................... EX38 8PH SWCP Point 5 i Bideford 9 2 MOORS WAY Natural Beauty (AONB) Clovelly 12 Coldharbour Mill ................................... EX15 3EE Hartland 1 i South 18 Bicton Park Botanical Gardens ...........EX9 7BG Molton National Parks A377 A39 2 22 Royal Albert Memorial Museum .........EX4 3RX Villages / small towns Mortehoe 23 Exeter Cathedral ...................... ..............EX1 1HS A388 3 i Great 24 Powderham Castle ..................................EX6 8JQ Torrington Tarka rail link Area centres Braunton 4 27 Bygones ................................................... TQ1 4PR Larger towns, showing 2 MOORS WAY approximate extent of Barnstaple 29 Kents Cavern ............................................TQ1 2JF Tarka Trail built up area. A386 A3124 i Tiverton 12 34 Buckfast Abbey ....................................TQ11 0EE Tourist Information Centres i A388 A377 11 A303 36 Morwellham Quay ................................. PL19 8JL Tourist Attraction (colour shows 10 Cullompton type of attraction. See Key to 0 A3072 Devon’s Top Attractions above). Activity Centres i Holsworthy Morchard Bishop Hatherleigh 35 River Dart Country Park ....................TQ13 7NP A373 A3072 A30 A3072 A377 Theme Parks & Farms A396 A3072 i Crediton A386 2 The Milky Way Adventure Park ......*EX39 5RY A388 i Honiton A35 Axminster 13 5 The Big Sheep ..................................... -

Start Point See the Website For: Attractions - Events - Online Discounts - Competitions - News

Lundy Island i Lynmouth Be inspired for a fabulous SWCP Lynton 5 A39 A399 Combe Martin A39 day out at Devon’s award Lee i Ilfracombe Mortehoe winning attractions Woolacombe A3123 A361 6 A39 Croyde Key to Map Saunton Braunton A399 Major roads - A classification A361 SWCP Heritage, Houses & Gardens i Barnstaple Tarka Trail River Taw Estuary SWCP Major roads - B classification Instow 1. Clovelly Village ................................... EX39 5TA A361 Long Distance Footpath Westward Ho A39 4. Dartington Crystal ............................ EX38 7AN Hartland Areas of Outstanding SWCP Point 3 i Bideford 9. Killerton House ...................................... EX5 3LE 7 2 MOORS WAY Natural Beauty (AONB) Clovelly Hartland 10. Coldharbour Mill & Country Park ....EX15 3EE 1 i South Molton National Parks A377 16. Bicton Park Botanical Gardens .........EX9 7BG A39 2 Villages / small towns Mortehoe 21. Exeter Cathedral ...................... ............EX1 1HS A388 4 i Great 23. Castle Drogo.......................................... EX6 6PB Torrington Tarka rail link Area centres Braunton 26. Bygones ..................................................TQ1 4PR Larger towns, showing 2 MOORS WAY approximate extent of Barnstaple 28. Kents Cavern ...........................................TQ1 2JF Tarka Trail built up area. A386 A3124 10 i Tiverton 31. Morwellham Quay ................................PL19 8JL Tourist Information Centres i A388 A377 11 A303 35. Buckfast Abbey .................................. TQ11 0EE Tourist Attraction (colour shows 8 Cullompton type of attraction. See Key to 0 A3072 Devon’s Top Attractions above). Activity Centres Morchard Bishop i A373 Holsworthy Hatherleigh A30 33. River Dart Adventures ..................... TQ13 7NP A3072 A3072 A377 A396 A3072 i Crediton A386 Theme Parks & Farms A388 9 Axminster 12 i Honiton A35 2. The Milky Way Adventure Park .... *EX39 5RY Tarka Trail i A375 Okehampton Exeter 3.