Trans- Appalachia a History Written for the Academy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

900 History, Geography, and Auxiliary Disciplines

900 900 History, geography, and auxiliary disciplines Class here social situations and conditions; general political history; military, diplomatic, political, economic, social, welfare aspects of specific wars Class interdisciplinary works on ancient world, on specific continents, countries, localities in 930–990. Class history and geographic treatment of a specific subject with the subject, plus notation 09 from Table 1, e.g., history and geographic treatment of natural sciences 509, of economic situations and conditions 330.9, of purely political situations and conditions 320.9, history of military science 355.009 See also 303.49 for future history (projected events other than travel) See Manual at 900 SUMMARY 900.1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901–909 Standard subdivisions of history, collected accounts of events, world history 910 Geography and travel 920 Biography, genealogy, insignia 930 History of ancient world to ca. 499 940 History of Europe 950 History of Asia 960 History of Africa 970 History of North America 980 History of South America 990 History of Australasia, Pacific Ocean islands, Atlantic Ocean islands, Arctic islands, Antarctica, extraterrestrial worlds .1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901 Philosophy and theory of history 902 Miscellany of history .2 Illustrations, models, miniatures Do not use for maps, plans, diagrams; class in 911 903 Dictionaries, encyclopedias, concordances of history 901 904 Dewey Decimal Classification 904 904 Collected accounts of events Including events of natural origin; events induced by human activity Class here adventure Class collections limited to a specific period, collections limited to a specific area or region but not limited by continent, country, locality in 909; class travel in 910; class collections limited to a specific continent, country, locality in 930–990. -

PEAES Guide: the Historical Society of Pennsylvania

PEAES Guide: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania http://www.librarycompany.org/Economics/PEAESguide/hsp.htm Keyword Search Entire Guide View Resources by Institution Search Guide Institutions Surveyed - Select One The Historical Society of Pennsylvania 1300 Locust Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 215-732-6200 http://www.hsp.org Overview: The entries in this survey highlight some of the most important collections, as well as some of the smaller gems, that researchers will find valuable in their work on the early American economy. Together, they are a representative sampling of the range of manuscript collections at HSP, but scholars are urged to pursue fruitful lines of inquiry to locate and use the scores of additional materials in each area that is surveyed here. There are numerous helpful unprinted guides at HSP that index or describe large collections. Some of these are listed below, especially when they point in numerous directions for research. In addition, the HSP has a printed Guide to the Manuscript Collections of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP: Philadelphia, 1991), which includes an index of proper names; it is not especially helpful for searching specific topics, item names, of subject areas. In addition, entries in the Guide are frequently too brief to explain the richness of many collections. Finally, although the on-line guide to the manuscript collections is generally a reproduction of the Guide, it is at present being updated, corrected, and expanded. This survey does not contain a separate section on land acquisition, surveying, usage, conveyance, or disputes, but there is much information about these subjects in the individual collections reviewed below. -

In Search of the Indiana Lenape

IN SEARCH OF THE INDIANA LENAPE: A PREDICTIVE SUMMARY OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT OF THE LENAPE LIVING ALONG THE WHITE RIVER IN INDIANA FROM 1790 - 1821 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY JESSICA L. YANN DR. RONALD HICKS, CHAIR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2009 Table of Contents Figures and Tables ........................................................................................................................ iii Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 Research Goals ............................................................................................................................ 1 Background .................................................................................................................................. 2 Chapter 2: Theory and Methods ................................................................................................. 6 Explaining Contact and Its Material Remains ............................................................................. 6 Predicting the Intensity of Change and its Effects on Identity................................................... 14 Change and the Lenape .............................................................................................................. 16 Methods .................................................................................................................................... -

The Journal of Mississippi History

The Journal of Mississippi History Volume LXXIX Fall/Winter 2017 No. 3 and No. 4 CONTENTS Death on a Summer Night: Faulkner at Byhalia 101 By Jack D. Elliott, Jr. and Sidney W. Bondurant The University of Mississippi, the Board of Trustees, Students, 137 and Slavery: 1848–1860 By Elias J. Baker William Leon Higgs: Mississippi Radical 163 By Charles Dollar 2017 Mississippi Historical Society Award Winners 189 Program of the 2017 Mississippi Historical Society 193 Annual Meeting By Brother Rogers Minutes of the 2017 Mississippi Historical Society 197 Business Meeting By Elbert R. Hilliard COVER IMAGE —William Faulkner on horseback. Courtesy of the Ed Meek digital photograph collection, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi. UNIV. OF MISS., THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES, STUDENTS, AND SLAVERY 137 The University of Mississippi, the Board of Trustees, Students, and Slavery: 1848-1860 by Elias J. Baker The ongoing public and scholarly discussions about many Americans’ widespread ambivalence toward the nation’s relationship to slavery and persistent racial discrimination have connected pundits and observers from an array of fields and institutions. As the authors of Brown University’s report on slavery and justice suggest, however, there is an increasing recognition that universities and colleges must provide the leadership for efforts to increase understanding of the connections between state institutions of higher learning and slavery.1 To participate in this vital process the University of Mississippi needs a foundation of research about the school’s own participation in slavery and racial injustice. The visible legacies of the school’s Confederate past are plenty, including monuments, statues, building names, and even a cemetery. -

Appalachia, Democracy, and Cultural Equity by Dudley Cocke

This article was originally published in 1993 in the book, "Voices from the Battlefront: Achieving Cultural Equity," edited by Marta Moreno Vega and Cheryll Y. Green; a Caribbean Cultural Center Book; Africa World Press, Inc. The article is based on presentations given by Dudley Cocke in 1989, 1990, and 1991 at a series of Cultural Diversity Based on Cultural Grounding conferences and follow-up meetings. Appalachia, Democracy, and Cultural Equity by Dudley Cocke A joke from the Depression goes: Two Black men are standing in a government breadline; one turns to the other, “How you making it?” The other looks up the line, “White folks still in the lead.” Although central Appalachia’s population is 98 percent white, the region joins the South Bronx, Bedford-Stuyvesant, and the Mississippi Delta at the bottom of the barrel in United States per capita income and college-educated adults. Two out of five students who make it to high school drop out before graduating, which is the worst dropout rate in the nation. Forty-two percent of the region’s adults are functionally illiterate. In eastern Kentucky’s Letcher County, half the children are classified as economically deprived, and almost a third of the area’s households exist on less than $10,000 a year. What’s the story here? Why are these white people doing so poorly? Part of the answer lies in the beginnings of the nation. 1 In the ascendancy of antidemocratic ideas such as those expressed by Alexander Hamilton and the Federalists were buried some of the seeds of Appalachia’s poverty. -

The 1758 Forbes Campaign and Its Influence on the Politics of the Province Of

The 1758 Forbes Campaign and its Influence on the Politics of the Province of Pennsylvania Troy Youhas Independence National Historical Park Intern January-May 2007 Submitted to: James W. Mueller, Ph.D. Chief Historian Independence National Historical Park 143 S. 3rd. Street Philadelphia, PA 19106 Although it often gets overlooked, the French and Indian War, or the War for Empire as it is now becoming known, was a very important turning point in United States History. While it was only a small part of a much larger scale war between Great Britain and France, it would bring about many changes on the North American continent. The immediate results of the war included the British acquisition of Canada and an almost immediate end to French presence in the North American colonies. The war also had the long term effects of establishing British dominance in the colonies and planting the seeds for the American Revolution. In the grand scheme of the war, the state of Pennsylvania would prove to be immensely important. While the war was being intensely debated among the assemblymen in the State House in Philadelphia, many important military events were taking place across the state. Not only did the French and Indian War establish places like Fort Duquesne and Fort Necessity as key historical sites, but it also involved some notable men in Pennsylvania and American history, such as Edward Braddock, James Abercrombie, and a then little known 21 year old Colonel by the name of George Washington. The major turning point of the war, and American history for that matter, was led by a Scottish-born General by the name of John Forbes, whose expedition across the state in 1758 forced the French to retreat from Fort Duquesne, a feat unsuccessfully attempted by Braddock three years earlier, and ultimately set the British on a course towards victory. -

Report Ofthe Council

Report ofthe Council October 21, ip8y AN ANNUAL MEETING marks the end ofan old year and the be- ginning of a new one. In that respect, this one is no different from the previous 174 during which you, our faithful members (or your predecessors), have suffered through narrations about the amazing successes, the fantastically exciting acquisitions, and the continu- ing upward ascent of our great and ever more elderly society. But this year has been a remarkable one for the American Antiquarian Society in terms of change, achievement, and, now, celebration. In this country, there are not very many secular institutions more ancient than ours, certainly not cultural ones—perhaps sixty col- leges, a handful of subscription libraries, a few learned societies. For 175 years we, and our friends of learning, have built and strengthened a great research library and its staff; have presented our collections to scholars and students of American history and life through service and publications; and now, at the beginning of our 176th year, are looking forward to new challenges to enable the Society to become even more useful as an agency of learning and to the understanding of our national life. Dealing with change takes first place in daily routine and there have been many important ones during the past twelve months, more so than in recent memory. Among the membership we lost a longtime friend and colleague, John Cushing. John served as librarian of the Massachusetts Historical Society since 1961 and during this past quarter century had been our constant col- laborator in worthwhile bibliographical and historical enterprises. -

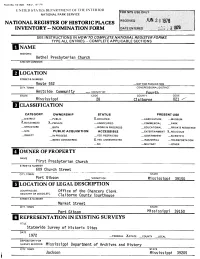

National Register of Historic Places Inventory « Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9 '77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY « NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS | NAME HISTORIC Bethel Presbyterian Church AND/OR COMMON LOCATION .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Wests ide Community __.VICINITY OF Fourth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Mississippi 28 Clai borne 021 ^*" BfCLA SSIFI C ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) X_PR| VATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT X-RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X_YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME First Presbyterian Church STREET & NUMBER 609 Church Street CITY, TOWN STATE Port Gibson VICINITY OF Mississippi 39150 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. Office of the Chancery Clerk REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. C1a1borne STREET & NUMBER Market Street CITY. TOWN STATE Port Gibson Mississippi 39150 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Statewide Survey of Historic Sites DATE 1972 —FEDERAL XSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Mississippi Department of Archives and History CITY. TOWN STATE Jackson Mississippi 39205 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE —RUINS X_ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Bethel Presbyterian Church, facing southwest on a grassy knoll on the east side of Route 552 north of Alcorn and approximately three miles from the Mississippi River shore, is representative of the classical symmetry and gravity expressed in the Greek Revival style. -

Indian Education for All Connecting Cultures & Classrooms K-12 Curriculum Guide (Language Arts, Science, Social Studies)

Indian Education for All Connecting Cultures & Classrooms K-12 Curriculum Guide (Language Arts, Science, Social Studies) Montana Office of Public Instruction Linda McCulloch, Superintendent In-state toll free 1-888-231-9393 www.opi.mt.gov/IndianEd Connecting Cultures and Classrooms INDIAN EDUCATION FOR ALL K-12 Curriculum Guide Language Arts, Science, Social Studies Developed by Sandra J. Fox, Ed. D. National Indian School Board Association Polson, Montana and OPI Spring 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................................... i Guidelines for Integrating American Indian Content ................. ii Using This Curriculum Guide ....................................................... 1 Section I Language Arts ...................................................................... 3 Language Arts Resources/Activities K-4 ............................ 8 Language Arts Resources/Activities 5-8 ............................. 16 Language Arts Resources/Activities 9-12 ........................... 20 Section II Science .................................................................................... 28 Science Resources/Activities K-4 ......................................... 36 Science Resources/Activities 5-8 .......................................... 42 Science Resources/Activities 9-12 ........................................ 50 Section III Social Studies ......................................................................... 58 Social Studies Resources/Activities K-4 ............................. -

ADVENTURES in the BIBLE BELT (The Charleston Gazette

ADVENTURES IN THE BIBLE BELT (The Charleston Gazette - 12/7/93) (reprinted in Fascinating West Virginia) By James A. Haught For many years, I was the Gazette's religion reporter and, believe me, I met some amazing denizens of Appalachia's Bible Belt. Does anyone remember Clarence "Tiz" Jones, the evangelist-burglar? Jones had been a West Virginia champion amateur boxer in his youth, but succumbed to booze and evil companions, and spent a hitch in state prison. Then he was converted and became a popular Nazarene revivalist. He roved the state, drawing big crowds, with many coming forward to be saved. But police noticed a pattern: In towns where Jones preached, burglaries happened. Eventually, officers charged him with a break-in. This caused a backlash among churches. Followers said Satan and his agents were framing the preacher. The Rev. John Hancock, a former Daily Mail reporter turned Nazarene pastor, led a "Justice for Tiz Jones" committee. Protest marches were held. Then Jones was nabbed red-handed in another burglary, and his guilt was clear. He went back to prison. Another spectacular West Virginia minister was "Dr." Paul Collett, a faith- healer who claimed he could resurrect the dead - if they hadn't been embalmed. Collett set up a big tent in Charleston and drew multitudes, including many in wheelchairs and on crutches. The healer said he had revived a corpse during a previous stop at Kenova. He urged believers to bring him bodies of loved ones, before embalming. Collett moved his show into the old Ferguson Theater and broadcast over Charleston radio stations. -

Daniel P. Barr Source: the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography , Jan., 2007, Vol

Victory at Kittanning? Reevaluating the Impact of Armstrong's Raid on the Seven Years' War in Pennsylvania Author(s): Daniel P. Barr Source: The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography , Jan., 2007, Vol. 131, No. 1 (Jan., 2007), pp. 5-32 Published by: University of Pennsylvania Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20093915 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20093915?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms University of Pennsylvania Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography This content downloaded from 64.9.56.53 on Sat, 19 Dec 2020 18:51:04 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms THE Pennsylvania OF HISTORYMagazine AND BIOGRAPHY Victory at Kittanning? Reevaluating the Impact of Armstrongs Raid on the Seven Years' War in Pennsylvania ON SEPTEMBER 8, 1756, Lieutenant Colonel John Armstrong led 307 men from the Second Battalion of the Pennsylvania Regiment in a daring raid against Kittanning, an important Delaware Indian village situated along the Allegheny River approximately forty miles upriver from the forks of the Ohio. -

River Raisin National Battlefield Park Lesson Plan Template

River Raisin National Battlefield Park 3rd to 5th Grade Lesson Plans Unit Title: “It’s Not My Fault”: Engaging Point of View and Historical Perspective through Social Media – The War of 1812 Battles of the River Raisin Overview: This collection of four lessons engage students in learning about the War of 1812. Students will use point of view and historical perspective to make connections to American history and geography in the Old Northwest Territory. Students will learn about the War of 1812 and study personal stories of the Battles of the River Raisin. Students will read and analyze informational texts and explore maps as they organize information. A culminating project will include students making a fake social networking page where personalities from the Battles will interact with one another as the students apply their learning in fun and engaging ways. Topic or Era: War of 1812 and Battles of River Raisin, United States History Standard Era 3, 1754-1820 Curriculum Fit: Social Studies and English Language Arts Grade Level: 3rd to 5th Grade (can be used for lower graded gifted and talented students) Time Required: Four to Eight Class Periods (3 to 6 hours) Lessons: 1. “It’s Not My Fault”: Point of View and Historical Perspective 2. “It’s Not My Fault”: Battle Perspectives 3. “It’s Not My Fault”: Character Analysis and Jigsaw 4. “It’s Not My Fault”: Historical Conversations Using Social Media Lesson One “It’s Not My Fault!”: Point of View and Historical Perspective Overview: This lesson provides students with background information on point of view and perspective.