Michael Talbot a MÔMO IMPRINT and “The Key”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caught in a Web of Deception Have Experienced the Phenomenon First Hand

seem to reflect poorly on their attempts to legitimize UFOs the bastard science of Ufology. One would also need to include in this group, those serious investigators who Caught in a Web of Deception have experienced the phenomenon first hand. A group of men and women who would much rather have lived This paper was originally presented at the out their days without adding an mib encounter to their Gulf Breeze UFO Conference, catalogue of life–experiences. Gulf Breeze Florida, February 12, 1994 Many relegate the mib question to some dusty men- © R. W. Boeche, 1994 All Rights Reserved tal shelf where they like to hide all of the oddball data they would rather not have to deal with in developing Today I intend to address the phenomenon of UFOs gen- theories regarding the UFO phenomena. This is the erally, by addressing an often-ridiculed, little-explored, shelf where they think they can safely put all of the real- subset of the UFO phenomenon. This area, known as ly wacky stuff. the Men-in-Black1 or mib phenomenon contains some This “really wacky stuff” has changed over time. Once, of the strangest and most bizarre events in the annals such things as UFO landings and sightings of UFO occu- of UFO research. And before anyone asks, I don’t mean pants were ignored by the ‘serious’ investigators for years. the Will Smith, Tommy Lee Jones movies. And then there is the problem of the contactees3: those What are UFOs? Some 85–95% of sightings have mun- chosen few who — beginning in the late 1940’s — were dane explanations. -

Rock & Roll's War Against

Rock & Roll’s War Against God Copyright 2015 by David W. Cloud ISBN 978-1-58318-183-6 Tis book is published for free distribution in eBook format. It is available in PDF, Mobi (for Kindle, etc.) and ePub formats from the Way of Life web site. See the Free eBook tab at www.wayofife.org. We do not allow distribution of our free books from other web sites. Published by Way of Life Literature PO Box 610368, Port Huron, MI 48061 866-295-4143 (toll free) - [email protected] www.wayofife.org Canada: Bethel Baptist Church 4212 Campbell St. N., London Ont. N6P 1A6 519-652-2619 Printed in Canada by Bethel Baptist Print Ministry ii Table of Contents Introduction ...........................................................................1 What Christians Should Know about Rock Music ...........5 What Rock Did For Me ......................................................38 Te History of Rock Music ................................................49 How Rock & Roll Took over Western Society ...............123 1950s Rock .........................................................................140 1960s Rock: Continuing the Revolution ........................193 Te Character of Rock & Roll .........................................347 Te Rhythm of Rock Music .............................................381 Rock Musicians as Mediums ...........................................387 Rock Music and Voodoo ..................................................394 Rock Music and Insanity ..................................................407 Rock Music and Suicide ...................................................429 -

New Age Tower of Babel Copyright 2008 by David W

The New Age Tower of Babel Copyright 2008 by David W. Cloud ISBN 978-1-58318-111-9 Published by Way of Life Literature P.O. Box 610368, Port Huron, MI 48061 866-295-4143 (toll free) • [email protected] (e-mail) http://www.wayoflife.org (web site) Canada: Bethel Baptist Church, 4212 Campbell St. N., London, Ont. N6P 1A6 • 519-652-2619 (voice) • 519-652-0056 (fax) • [email protected] (e-mail) Printed in Canada by Bethel Baptist Print Ministry 2 CONTENTS I. The New Age’s Vain Dream ....................................................5 II. Oprah Winfrey: The New Age High Priestess ......................10 III. My Experience in the New Age ..........................................27 IV. The New Age and the Mystery of Iniquity ..........................32 V. What Is the New Age? ..........................................................36 VI. The Origin of the New Age .................................................47 VII. How the New Age Evolved over the Past 100 Years .........61 The Stage Was Set at the Turn of the 20th Century The Mind Science Cults ................................................62 Christian Science ...........................................................64 Unity School of Christianity .........................................69 Helena Blavatsky and Theosophy .................................72 Alice Bailey ...................................................................80 The New Thought Positive-Confession Movement ......85 Aldous Huxley ..............................................................91 Alan -

Psychic Experiences Explained

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol. 16PSYCHI No. 4 C EXPERIENCES EXPLAINED The Scientist's Skepticism The Paranormal's Popularity Self-Help Books/Ghost Lights Published by the Commute Investigation of Claims of the PParanormaa an l THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER (ISSN 0194-6730) is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, an international organization. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz. Consulting Editors Isaac Asimov, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, David F. Marks, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Contributing Editor Lys Ann Shore. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Assistant Business Manager Sandra Lesniak Chief Data Officer Richard Seymour. Computer Assistant Michael Cione. Production Paul E. Loynes. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian, Ranjit Sandhu. Staff Leland Harrington, Jonathan Jiras, Atfreda Pidgeon, Kathy Reeves, Elizabeth Begley (Albuquerque). Cartoonist Rob Pudim. The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo. Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock, psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Isaac Asimov, biochemist, author; Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky; Barry Beyerstein, biopsychologist, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, B.C., Canada; Irving Biederman, psychologist, University of Minnesota; Susan Blackmore, psychologist, Brain Perception Laboratory, University of Bristol, England; Henri Broch, physicist, University of Nice, France; Vern Bullough, Distinguished Professor, State University of New York; Mario Bunge, philosopher, McGill University; John R. -

A Futures Vision of Sacredness As the Formative Base of Democratic Governing: Source, Model and Transformation of Spirituality Into Government

A futures vision of sacredness as the formative base of democratic governing: source, model and transformation of spirituality into government. Candidate: Rosemary Jane Beaumont MA BSc Dip Ed This thesis is submitted for the Doctor of Philosophy degree as the total fulfilment of the requirements for that degree. School of Education University of Western Sydney June 2006 University of Western Sydney Candidate’s certificate I certify that this thesis entitled A futures vision of sacredness as the formative base of democratic governing: source, model and transformation of spirituality into government submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy is the result of my own research, except where otherwise acknowledged, and that this thesis in whole or part has not been submitted for an award including a higher degree to any other university or institution. Signed: Name: Rosemary Jane Beaumont Date: Acknowledgements In this journey of exploration I thank my family and friends who have given encouragement and sustaining faith in the value of this endeavour – in particular Di and Sol. My thanks go also to the generosity of the research participants. My supervisor, Susan Murphy, said at our first meeting that she would ‘hold the space’ for this project – and she has. I am grateful to the Faculty of Social Ecology, UWS, for its openness to many ways of knowing. My wish is that this research contributes to expanding the options and discussion space for evolving inherently inclusive and sustainable forms of democracy. Table of Contents Chapter one: -

Academy of Intuition Medicine® & Energy Medicine University

Academy of Intuition Medicine® & Energy Medicine University School Catalog Effective October 1, 2018 Mail: PO Box 1921 Mill Valley, California 94942 USA Campus: 2400 Bridgeway Suite 290, Sausalito, California 94965 www.IntuitionMedicine.org Academy of Intuition Medicine® & Energy Medicine University Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Purpose ......................................................................................................................................................... 6 People ........................................................................................................................................................... 6 Advisory Board .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Staff ........................................................................................................................................................... 7 Affiliations ..................................................................................................................................................... 8 Location and Facilities ................................................................................................................................... 9 Library .......................................................................................................................................................... -

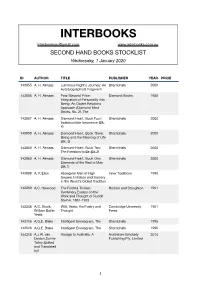

Second Hand Jan 2020

INTERBOOKS [email protected] www.interbooks.com.au SECOND HAND BOOKS STOCKLIST Wednesday, 1 January 2020 ID AUTHOR TITLE PUBLISHER YEAR PRICE 143055 A. H. Almaas Luminous Night's Journey: An Shambhala 2000 Autobiographical Fragment 143056 A. H. Almaas Pearl Beyond Price: Diamond Books 1988 Integration of Personality into Being: An Object Relations Approach (Diamond Mind Series, No. 2), The 143057 A. H. Almaas Diamond Heart, Book Four: Shambhala 2000 Indestructible Innocence (Bk. 4) 143058 A. H. Almaas Diamond Heart, Book Three: Shambhala 2000 Being and the Meaning of Life (Bk. 3) 143059 A. H. Almaas Diamond Heart, Book Two: Shambhala 2000 The Freedom to Be (Bk.2) 143060 A. H. Almaas Diamond Heart, Book One: Shambhala 2000 Elements of the Real in Man (Bk.1) 143088 A. P. Elkin Aboriginal Men of High Inner Traditions 1993 Degree: Initiation and Sorcery in the World's Oldest Tradition 143359 A.C. Harwood The Faithful Thinker: Hodder and Stoughton 1961 Centenary Essays on the Work and Thought of Rudolf Steiner, 1861-1925 143348 A.G. Stock, W.B. Yeats: His Poetry and Cambridge University 1961 William Butler Thought Press Yeats 143116 A.G.E. Blake Intelligent Enneagram, The Shambhala 1996 143516 A.G.E. Blake Intelligent Enneagram, The Shambhala 1996 144318 A.J.W. van Voyage to Australia, A Australian Scholarly 2014 Delden,Dorine Publishing Pty, Limited Tolley (Edited and Translated by) !1 ID AUTHOR TITLE PUBLISHER YEAR PRICE 144236 A.L. Where Is Bernardino? Two Rivers Press 1982 Staveley,Nonny Hogrogian 143361 A.L. Stavely Themes: I Two Rivers Press 143362 A.L. -

Your Past Lives

1 Your Past Lives A REINCARNATION HANDBOOK Michael Talbot Copyright © 1987 by Michael Talbot All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Published by Harmony Books, a division of Crown Publishers, Inc., 225 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003 and represented in Canada by the Canadian MANDA Group HARMONY and colophon are trademarks of Crown Publishers, Inc. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Talbot, Michael Your past lives. 1. Reincarnation. I. Title. BL515.T35 1987 133.9'01'3 87-8803 ISBN 0-517-56301-0 10 987654321 First Edition For Carol Dryer, to whom I owe more than words can express Table of Contents Acknowledgments ............................................................................................. i Preface ............................................................................................................. ii Introduction ..................................................................................................... 1 Part One: Exploring Alone 1. Preparing ............................................................................................... 13 2. The Resonance Method .......................................................................... 25 3. Dreaming Technique ............................................................................. -

Worldviews in Transition: a Study of the New Age Movement in South Africa

WORLDVIEWS IN TRANSITION: A STUDY OF THE NEW AGE MOVEMENT IN SOUTH AFRICA by HELENA CHRISTINA STEYN submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY in the subject RELIGIOUS STUDIES atthe UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER: PROF J S KRiiGER CO-PROMOTER: DR W J SCHURINK NOVEMBER 1992 This thesis is dedicated to my mother ~'·\RY I ·'::'.' . 1~83 ·07- J ~ 299 '930 968 STEY Xla~ I·\~~ees ! '.''2:~'~.~c= 1111111111111 01491843 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my profound appreciation to: Prof JS Kri.iger, my promoter and mentor, who has carefully guided my studies since my first introduction to Religious Studies thirteen years ago. It was he who inspired me to embark on this project and whose thoughtful, patient guidance and encour agement subsequently enabled me to persevere and bring this project to fruition. Dr W J Schurink, my co-promoter and a pioneer in the actualisation of the qualita tive research method in South Africa. He kept a watchful eye on the methodology of this project and astutely steered me through the many pitfalls inherent in a qualitative study. The Centre for Research Development (HSRC, South Africa) who sponsored the project and made available a significant grant. The opinions and conclusions in this study are, however, my own and cannot be attributed to the Centre. Monica Strassner, Saretha Botha and Cariena Zeelie, the subject reference librar ians who cheerfully and efficiently shouldered much of the responsibility for obtain ing the many books and articles that the study required. Yvonne Kemp, who skilfully edited the thesis, and Thea Eicker who assisted with the many intricacies that still elude me of working on a PC. -

Editorial Master List Alex Burns ([email protected]), 1999—2002

1 Disinformation® Editorial Master List Alex Burns ([email protected]), 1999—2002 Comment (21st November 2007) I first heard of the US-based subculture site Disinformation® when RU Sirius profiled Richard Metzger for a 1997 issue of Australia’s 21C Magazine. When 21C ceased publication in 1998 Metzger suggested I write for Disinfo. I became the site’s editor in November 1999 when Metzger began pre-production and shooting the Disinfo Nation television series for the United Kingdom’s Channel 4. “The Internet can be like a black hole,” he warned me in an email. For the next several years Disinfo ran a popular ‘webzine’ with dossier profiles of forbidden knowledge, current socio-political issues and subcultural icons. Publisher Gary Baddeley and I worked with a variety of writers including Sara Aronson, Nick Mamatas and Preston Peet. But by 2002 the dotcom bubble had burst, the pre-millennial tension had ebbed, the September 11 terrorist attacks had occurred, and I was fast approaching editorial burnout. Disinfo’s Russ Kick took over editing the site before establishing his influential Alternewswire and Memory Hole projects. When I returned to the editorial helm, we soon had a new site version and a “day’s best links” format. In 2007 we launched a user-driven version that enabled fresh fever from the skies. During the ‘classic’ era Disinformation attracted both praise and criticism—often from the same person. Our fans understood that Metzger and I both drew on diverse sources for Disinformation’s editorial philosophy such as Jello Biafra’s injunctive to “become the media”, Noam Chomsky and Edward S.