`The Unique Structure of the Present Great Andamanese: an Overview of the Grammar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grammatical Gender in Hindukush Languages

Grammatical gender in Hindukush languages An areal-typological study Julia Lautin Department of Linguistics Independent Project for the Degree of Bachelor 15 HEC General linguistics Bachelor's programme in Linguistics Spring term 2016 Supervisor: Henrik Liljegren Examinator: Bernhard Wälchli Expert reviewer: Emil Perder Project affiliation: “Language contact and relatedness in the Hindukush Region,” a research project supported by the Swedish Research Council (421-2014-631) Grammatical gender in Hindukush languages An areal-typological study Julia Lautin Abstract In the mountainous area of the Greater Hindukush in northern Pakistan, north-western Afghanistan and Kashmir, some fifty languages from six different genera are spoken. The languages are at the same time innovative and archaic, and are of great interest for areal-typological research. This study investigates grammatical gender in a 12-language sample in the area from an areal-typological perspective. The results show some intriguing features, including unexpected loss of gender, languages that have developed a gender system based on the semantic category of animacy, and languages where this animacy distinction is present parallel to the inherited gender system based on a masculine/feminine distinction found in many Indo-Aryan languages. Keywords Grammatical gender, areal-typology, Hindukush, animacy, nominal categories Grammatiskt genus i Hindukush-språk En areal-typologisk studie Julia Lautin Sammanfattning I den här studien undersöks grammatiskt genus i ett antal språk som talas i ett bergsområde beläget i norra Pakistan, nordvästra Afghanistan och Kashmir. I området, här kallat Greater Hindukush, talas omkring 50 olika språk från sex olika språkfamiljer. Det stora antalet språk tillsammans med den otillgängliga terrängen har gjort att språken är arkaiska i vissa hänseenden och innovativa i andra, vilket gör det till ett intressant område för arealtypologisk forskning. -

A Comparative Phonetic Study of the Circassian Languages Author(S

A comparative phonetic study of the Circassian languages Author(s): Ayla Applebaum and Matthew Gordon Proceedings of the 37th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society: Special Session on Languages of the Caucasus (2013), pp. 3-17 Editors: Chundra Cathcart, Shinae Kang, and Clare S. Sandy Please contact BLS regarding any further use of this work. BLS retains copyright for both print and screen forms of the publication. BLS may be contacted via http://linguistics.berkeley.edu/bls/. The Annual Proceedings of the Berkeley Linguistics Society is published online via eLanguage, the Linguistic Society of America's digital publishing platform. A Comparative Phonetic Study of the Circassian Languages1 AYLA APPLEBAUM and MATTHEW GORDON University of California, Santa Barbara Introduction This paper presents results of a phonetic study of Circassian languages. Three phonetic properties were targeted for investigation: voice-onset time for stop consonants, spectral properties of the coronal fricatives, and formant values for vowels. Circassian is a branch of the Northwest Caucasian language family, which also includes Abhaz-Abaza and Ubykh. Circassian is divided into two dialectal subgroups: West Circassian (commonly known as Adyghe), and East Circassian (also known as Kabardian). The West Circassian subgroup includes Temirgoy, Abzekh, Hatkoy, Shapsugh, and Bzhedugh. East Circassian comprises Kabardian and Besleney. The Circassian languages are indigenous to the area between the Caspian and Black Seas but, since the Russian invasion of the Caucasus region in the middle of the 19th century, the majority of Circassians now live in diaspora communities, most prevalently in Turkey but also in smaller outposts throughout the Middle East and the United States. -

THE INDO-EUROPEAN FAMILY — the LINGUISTIC EVIDENCE by Brian D

THE INDO-EUROPEAN FAMILY — THE LINGUISTIC EVIDENCE by Brian D. Joseph, The Ohio State University 0. Introduction A stunning result of linguistic research in the 19th century was the recognition that some languages show correspondences of form that cannot be due to chance convergences, to borrowing among the languages involved, or to universal characteristics of human language, and that such correspondences therefore can only be the result of the languages in question having sprung from a common source language in the past. Such languages are said to be “related” (more specifically, “genetically related”, though “genetic” here does not have any connection to the term referring to a biological genetic relationship) and to belong to a “language family”. It can therefore be convenient to model such linguistic genetic relationships via a “family tree”, showing the genealogy of the languages claimed to be related. For example, in the model below, all the languages B through I in the tree are related as members of the same family; if they were not related, they would not all descend from the same original language A. In such a schema, A is the “proto-language”, the starting point for the family, and B, C, and D are “offspring” (often referred to as “daughter languages”); B, C, and D are thus “siblings” (often referred to as “sister languages”), and each represents a separate “branch” of the family tree. B and C, in turn, are starting points for other offspring languages, E, F, and G, and H and I, respectively. Thus B stands in the same relationship to E, F, and G as A does to B, C, and D. -

The Dravidian Languages

THE DRAVIDIAN LANGUAGES BHADRIRAJU KRISHNAMURTI The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarc´on 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Bhadriraju Krishnamurti 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Times New Roman 9/13 pt System LATEX2ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0521 77111 0hardback CONTENTS List of illustrations page xi List of tables xii Preface xv Acknowledgements xviii Note on transliteration and symbols xx List of abbreviations xxiii 1 Introduction 1.1 The name Dravidian 1 1.2 Dravidians: prehistory and culture 2 1.3 The Dravidian languages as a family 16 1.4 Names of languages, geographical distribution and demographic details 19 1.5 Typological features of the Dravidian languages 27 1.6 Dravidian studies, past and present 30 1.7 Dravidian and Indo-Aryan 35 1.8 Affinity between Dravidian and languages outside India 43 2 Phonology: descriptive 2.1 Introduction 48 2.2 Vowels 49 2.3 Consonants 52 2.4 Suprasegmental features 58 2.5 Sandhi or morphophonemics 60 Appendix. Phonemic inventories of individual languages 61 3 The writing systems of the major literary languages 3.1 Origins 78 3.2 Telugu–Kannada. -

Turkic Languages 161

Turkic Languages 161 seriously endangered by the UNESCO red book on See also: Arabic; Armenian; Azerbaijanian; Caucasian endangered languages: Gagauz (Moldovan), Crim- Languages; Endangered Languages; Greek, Modern; ean Tatar, Noghay (Nogai), and West-Siberian Tatar Kurdish; Sign Language: Interpreting; Turkic Languages; . Caucasian: Laz (a few hundred thousand speakers), Turkish. Georgian (30 000 speakers), Abkhaz (10 000 speakers), Chechen-Ingush, Avar, Lak, Lezghian (it is unclear whether this is still spoken) Bibliography . Indo-European: Bulgarian, Domari, Albanian, French (a few thousand speakers each), Ossetian Andrews P A & Benninghaus R (1989). Ethnic groups in the Republic of Turkey. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert (a few hundred speakers), German (a few dozen Verlag. speakers), Polish (a few dozen speakers), Ukranian Aydın Z (2002). ‘Lozan Antlas¸masında azınlık statu¨ su¨; (it is unclear whether this is still spoken), and Farklı ko¨kenlilere tanınan haklar.’ In Kabog˘lu I˙ O¨ (ed.) these languages designated as seriously endangered Azınlık hakları (Minority rights). (Minority status in the by the UNESCO red book on endangered lan- Treaty of Lausanne; Rights granted to people of different guages: Romani (20 000–30 000 speakers) and Yid- origin). I˙stanbul: Publication of the Human Rights Com- dish (a few dozen speakers) mission of the I˙stanbul Bar. 209–217. Neo-Aramaic (Afroasiatic): Tu¯ ro¯ yo and Su¯ rit (a C¸ag˘aptay S (2002). ‘Otuzlarda Tu¨ rk milliyetc¸ilig˘inde ırk, dil few thousand speakers each) ve etnisite’ (Race, language and ethnicity in the Turkish . Languages spoken by recent immigrants, refugees, nationalism of the thirties). In Bora T (ed.) Milliyetc¸ilik ˙ ˙ and asylum seekers: Afroasiatic languages: (Nationalism). -

LING 185 the Syntax of Austronesian Languages Preliminary Syllabus

LING 185 The Syntax of Austronesian Languages Preliminary syllabus The goal of this class is to provide an introduction into comparative Austronesian syntax by discussing the most pertinent issues of Austronesian languages that have posed challenge to current syntactic theory and suggesting further readings and topics for discussion. The choice of the Austronesian language family as the focus of this class is not accidental. The Austronesian language family—roughly 1,200 genetically related languages dispersed over an area encompassing Madagascar, Taiwan, Southeast Asia, and islands of the Pacific—is often called the largest language family in the world. But it has been relatively little studied. Sophisticated research on the grammar of Austronesian languages did not really begin until the 1930’s and 1940’s (fueled, in part, by military interest in the Pacific region). Although there was a surge of interest in Austronesian in the 1970’s and—even more dramatically—in the 1990’s, the number of theoretical linguists working on these languages has remained small. Nonetheless, Austronesian languages have a significant contribution to make to linguistic theory, given the number of typologically unusual properties they exhibit (including the less common and poorly understood verb‐first word order, ergativity, and wh‐ agreement). If these languages were as well‐understood as, say, the Romance languages are today, syntactic theory could well be dramatically different. The following list illustrates just some of the intriguing features whose theoretical significance—already evident—will surely deepen when they are investigated from a comparative perspective: • Many Austronesian languages exhibit the uncommon word orders verb‐subject‐object (VSO) or verb‐object‐subject (VOS). -

Downloaded Dataset, and the Bi-Labelled Individual Completely Removed

An exploratory analysis of combined genome-wide SNP data from several recent studies Blaise Li Abstract The usefulness of a ‘total-evidence’ approach to human population genetics was assessed through a clustering analysis of combined genome-wide SNP datasets. The combination contained only 3146 SNPs. Detailed examination of the results nonetheless enables the extraction of relevant clues about the history of human populations, some pertaining to events as ancient as the first migration out of Africa. The results are mostly coherent with what is known from history, linguistics, and previous genetic analyses. These promising results suggest that cross-studies data confrontation have the potential to yield interesting new hypotheses about human population history. Key words: Data combination, Graphical representation, Human populations, Single nucleotide polymorphism 1. Introduction Let this introduction begin with a disclaimer: I am not a population geneti- cist, but a phylogeneticist who happens to be interested in human popula- tion history. The results presented here should not be considered as scientific claims about human population histories, but only as hypotheses that might deserve further investigation. arXiv:1101.5519v4 [q-bio.PE] 6 Dec 2012 In human population genetics, numerous papers have recently been pub- lished using genome-wide SNP (Single Nucleotide Polymorphism) data for populations of various places in the world. These papers often represent the data by means of PCA (Principal Component Analysis) plots or clustering bar plots. The details of such graphical representations suggest a variety of interesting hypotheses concerning the relationships between populations. However, it is frustrating to see the data scattered between different studies. -

In Search of Language Contact Between Jarawa and Aka-Bea: the Languages of South Andaman1

Acta Orientalia 2011: 72, 1–40. Copyright © 2011 Printed in India – all rights reserved ACTA ORIENTALIA ISSN 0001-6483 In search of language contact between Jarawa and Aka-Bea: The languages of South Andaman1 Anvita Abbi and Pramod Kumar Cairns Institute, Cairns, Australia & Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Abstract The paper brings forth a preliminary report on the comparative data available on the extinct language Aka-Bea (Man 1923) and the endangered language Jarawa spoken in the south and the central parts of the Andaman Islands. Speakers of Aka-Bea, a South Andaman language of the Great Andamanese family and the speakers of Jarawa, the language of a distinct language family (Abbi 2006, 2009, Blevins 2008) lived adjacent to each other, i.e. in the southern region of the Great Andaman Islands in the past. Both had been hunter-gatherers and never had any contact with each other (Portman 1899, 1990). The Jarawas have been known for living in isolation for thousands of years, coming in contact with the outside world only recently in 1998. It is, then surprising to discover traces of some language-contact in the past between the two communities. Not a large database, but a few examples of lexical similarities between Aka-Bea and Jarawa are 1 The initial version of this paper was presented in The First Conference on ASJP and Language Prehistory (ALP-I), on 18 September 2010, Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany. We thank Alexandra Aikhnevald for helpful comments on an earlier version of the paper. 2 Anvita Abbi & Pramod Kumar investigated here. -

Unconventional Linguistic Clues to the Negrito Past Robert Blust University of Hawai‘I, Honolulu, Hawai‘I, [email protected]

Human Biology Volume 85 Issue 1 Special Issue on Revisiting the "Negrito" Article 18 Hypothesis 2013 Terror from the Sky: Unconventional Linguistic Clues to the Negrito Past Robert Blust University of Hawai‘i, Honolulu, Hawai‘i, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol Part of the Anthropological Linguistics and Sociolinguistics Commons, and the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Blust, Robert (2013) "Terror from the Sky: Unconventional Linguistic Clues to the Negrito Past," Human Biology: Vol. 85: Iss. 1, Article 18. Available at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol/vol85/iss1/18 Terror from the Sky: Unconventional Linguistic Clues to the Negrito Past Abstract Within recorded history. most Southeast Asian peoples have been of "southern Mongoloid" physical type, whether they speak Austroasiatic, Tibeto-Burman, Austronesian, Tai-Kadai, or Hmong-Mien languages. However, population distributions suggest that this is a post-Pleistocene phenomenon and that for tens of millennia before the last glaciation ended Greater Mainland Southeast Asia, which included the currently insular world that rests on the Sunda Shelf, was peopled by short, dark-skinned, frizzy-haired foragers whose descendants in the Philippines came to be labeled by the sixteenth-century Spanish colonizers as "negritos," a term that has since been extended to similar groups throughout the region. There are three areas in which these populations survived into the present so as to become part of written history: the Philippines, the Malay Peninsula, and the Andaman Islands. All Philippine negritos speak Austronesian languages, and all Malayan negritos speak languages in the nuclear Mon-Khmer branch of Austroasiatic, but the linguistic situation in the Andamans is a world apart. -

Unique Origin of Andaman Islanders: Insight from Autosomal Loci

J Hum Genet (2006) 51:800–804 DOI 10.1007/s10038-006-0026-0 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Unique origin of Andaman Islanders: insight from autosomal loci K. Thangaraj Æ G. Chaubey Æ A. G. Reddy Æ V. K. Singh Æ L. Singh Received: 9 April 2006 / Accepted: 1 June 2006 / Published online: 19 August 2006 Ó The Japan Society of Human Genetics and Springer-Verlag 2006 Abstract Our mtDNA and Y chromosome studies Introduction lead to the conclusion that the Andamanese ‘‘Negrito’’ mtDNA lineages have survived in the Andaman Is- The ‘‘Negrito’’ populations found scattered in parts of lands in complete genetic isolation from other South southern India, the Andaman Islands, Malaysia and the and Southeast Asian populations since the initial set- Philippines are considered to be the relic of early tlement of the region by the out-of-Africa migration. In modern humans and hence assume considerable order to obtain a robust reconstruction of the evolu- anthropological and genetic importance. Their gene tionary history of the Andamanese, we carried out a pool is slowly disappearing either due to assimilation study on the three aboriginal populations, namely, the with adjoining populations, as in the case of the Se- Great Andamanese, Onge and Nicobarese, using mang of Malaysia and Aeta of the Philippines, or due autosomal microsatellite markers. The range of alleles to their population collapse, as is evident in the case of (7–31.2) observed in the studied population and het- the aboriginals of the Andaman Islands. The Andaman erozygosity values (0.392–0.857) indicate that the se- and Nicobar Islands are inhabited by six enigmatic lected STR markers are highly polymorphic in all the indigenous tribal populations, of which four have been three populations, and genetic variability within the characterized traditionally as ‘‘Negritos’’ (the Jarawa, populations is significantly high, with a mean gene Onge, Sentinelese and Great Andamanese) and two as diversity of 77%. -

The Jarawa of the Andamans

Te Jarawa of the Andamans Rhea John and Harsh Mander* India’s Andaman Islands are home to some of the some scholars describe appropriately as ‘adverse most ancient, and until recently the most isolated, inclusion’.1 Te experience of other Andaman tribes peoples in the world. Today barely a few hundred like the Great Andamanese and the Onge highlight of these peoples survive. Tis report is about one of poignantly and sombrely the many harmful these ancient communities of the Andaman Islands, consequences of such inclusion.2 Te continued the Jarawa, or as they describe themselves, the Ang. dogged resistance of the Sentinelese to any contact with outsiders makes them perhaps the most Until the 1970s, and even to a degree until the isolated people in the world. On the other hand, 1990s, the Jarawa people fercely and ofen violently the early adverse consequences of exposure of the defended their forest homelands, fghting of a Jarawa people to diseases and sexual exploitation diverse range of incursions and ofers of ‘friendly’ by outsiders, suggest that safeguarding many forms contact—by other tribes-people, colonial rulers, of ‘exclusion’ may paradoxically constitute the best convicts brought in from mainland India by the chance for the just and humane ‘inclusion’ of these colonisers, the Japanese occupiers, independent highly vulnerable communities. India’s administration, and mainland communities settled on the islands by the Indian government. Since However, the optimal balance between isolation the 1990s, two of the three main Ang communities and contact with the outside world of such have altered their relationship with the outsider of indigenous communities is something that no many hues, accepting their ‘friendship’ and all that government in the modern world has yet succeeded came with it, including health care support, clothes, in establishing. -

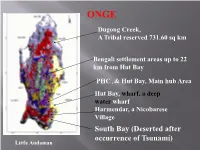

South Bay (Deserted After Occurrence of Tsunami)

ONGE Dugong Creek, A Tribal reserved 731.60 sq km Bengali settlement areas up to 22 km from Hut Bay PHC , & Hut Bay, Main hub Area Hut Bay, wharf, a deep water wharf Harmendar, a Nicobarese Village South Bay (Deserted after occurrence of Tsunami) Little Andaman Little Andaman (LA) Island once was exclusively the abode of the OG until early 1960s OG tribe, settled at Dugong Creek (DC) & South Bay, LA in 1978 Post-Tsunami situation relocated them a little away from DC The geographical isolation of Dugong and South Bay offers a secure resemblance of nomadic pursuits, and the tropical rain forest, ecology, creeks, rivulets, sea etc are conducive to sustain foraging activities throughout the year. Age-wise population Age Male Female Total Sex group) (in years) N % N % N % Ratio 0-10 25 53.19 22 46.81 47 100 880 11-20 11 57.89 08 42.11 19 100 727 21-30 07 53.85 06 46.15 13 100 857 31-40 03 30 07 70 10 100 2333 41-50 03 42.85 04 57.15 07 100 1333 51+ 04 36.36 07 63.64 11 100 1750 53 49.53 54 50.47 107 100 1019 *AAJVS *Till June 2012 Socio-Economic condition of the Onge As semi-nomad forager, hunting & fishing were their fortes, fond of dugong that they hunt on full moon night Being animists, belief on ancestral assistance in various foraging activities Observed adolescent ritual for a month long usually followed by smearing their bodies & hunting as well Body painting with red ochre & white clay common Dead is buried under the large bedstead in the hut, which is then deserted Monogamy stringently adhered to as marriage rules, re-marriage of widow or widower allowable Pre-tsunami situation, Dugong Creek Onge settlement deserted Post-tsunami situation, Dugong Creek Intrinsic designs, which are usually painted by womenfolk on their loving spouses & on themselves too.