Master's Thesis a Romance for the Ages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Gender Resistance in Romantic Friendships Between

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects 2012 Deviant Desires: Gender Resistance in Romantic Friendships Between Women during the Late- Eighteenth and Early-Nineteenth Centuries in Britain Sophie Jade Slater Minnesota State University - Mankato Follow this and additional works at: http://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds Part of the Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Slater, Sophie Jade, "Deviant Desires: Gender Resistance in Romantic Friendships Between Women during the Late-Eighteenth and Early-Nineteenth Centuries in Britain" (2012). Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects. Paper 129. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Slater i Deviant Desires: Gender Resistance in Romantic Friendships Between Women during the Late- Eighteenth and Early-Nineteenth Centuries in Britain By Sophie Slater A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Gender and Women’s Studies Minnesota State University, Mankato Mankato, Minnesota May 2012 Slater ii April 3, 2012 This thesis paper has been examined and approved. Examining Committee: Dr. Maria Bevacqua, Chairperson Dr. Christopher Corley Dr. Melissa Purdue Slater iii Abstract Romantic friendships between women in the late-eighteenth and early- nineteenth centuries were common in British society. -

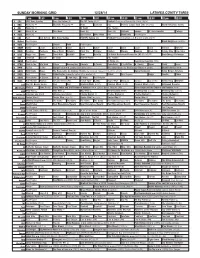

Sunday Morning Grid 12/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Chargers at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News 1st Look Paid Premier League Goal Zone (N) (TVG) World/Adventure Sports 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Outback Explore St. Jude Hospital College 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Philadelphia Eagles at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Black Knight ›› (2001) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Play. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Happy Feet ››› (2006) Elijah Wood. -

Postfeminism and Urban Space Oddities in Broad City." Space Oddities: Difference and Identity in the American City

Lahm, Sarah. "'Yas Queen': Postfeminism and Urban Space Oddities in Broad City." Space Oddities: Difference and Identity in the American City. Ed. Stefan L. Brandt and Michael Fuchs. Vienna: LIT Verlag, 2018. 161-177. ISBN 978-3-643-50797-6 (pb). "VAS QUEEN": POSTFEMINISM AND URBAN SPACE ODDITIES IN BROAD CITY SARAH LAHM Broad City's (Comedy Central, since 2014) season one episode "Working Girls" opens with one of the show's most iconic scenes: In the show's typical fashion, the main characters' daily routines are displayed in a split screen, as the scene underline the differ ences between the characters of Abbi and Ilana and the differ ent ways in which they interact with their urban environment. Abbi first bonds with an older man on the subway because they are reading the same book. However, when he tries to make ad vances, she rejects them and gets flipped off. In clear contrast to Abbi's experience during her commute to work, Ilana intrudes on someone else's personal space, as she has fallen asleep on the subway and is leaning (and drooling) on a woman sitting next to her (who does not seem to care). Later in the day, Abbi ends up giving her lunch to a homeless person who sits down next to her on a park bench, thus fitting into her role as the less assertive, more passive of the two main characters. Meanwhile, Ilana does not have lunch at all, but chooses to continue sleeping in the of ficebathroom, in which she smoked a joint earlier in the day. -

What Will It Take to Save Comedy Central?

What Will it Take to Save Comedy Central? 08.16.2016 Comedy Central's cancellation of The Nightly Show is the latest in a series of signals that all is not well at the network that was once the home of the country's sharpest political satire and news commentary. On Monday, Comedy Central announced that it was cancelling the show, which took Stephen Colbert's Colbert Report time slot in February 2015 when Colbert moved over to CBS' The Late Show. The move was not surprising considering the ratings: The Nightly Show is averaging a barely-there 0.2 among its key demographic of adults 18-49. RELATED: Comedy Central Cancels 'The Nightly Show' But The Nightly Show's failure to catch on is not the only problem at Comedy Central. Consider its late-night partner, The Daily Show, long the network's marquee program with host Jon Stewart. Stewart left the show just over a year ago and was replaced with South African comic Trevor Noah, who was hand-picked by Stewart. But despite Comedy Central's best efforts to reassure the media and audiences that Noah would eventually catch on, so far he hasn't. In May, The Wrap reported that The Daily Show had lost 38% of Stewart's audience among millennials aged 18-34 and 35% in households. And that comes at a time when the country is in the middle of a presidential election that lends itself extremely well to satire. It's also proven to be a mistake to let so much of its talent walk out the door, with Stephen Colbert going to CBS, John Oliver to HBO and Samantha Bee to TBS, taking much of Comedy Central's brand equity with them. -

Uma Tradução Comentada De "The Other Boat" Florianópolis – 20

Garibaldi Dantas de Oliveira O Outro E. M. Forster: uma tradução comentada de "The other boat" Florianópolis – 2015 Garibaldi Dantas de Oliveira O Outro E. M. Forster: uma tradução comentada de "The other boat" Tese submetida ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Estudos da Tradução da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina para a obtenção do título de Doutor em Estudos da Tradução. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Walter Carlos Costa Florianópolis – 2015 Ficha de identificação da obra elaborada pelo autor, através do Programa de Geração Automática da Biblioteca Universitária da UFSC OLIVEIRA, Garibaldi Dantas de. O Outro E. M. Forster: uma tradução comentada de "The other boat" [tese] / Garibaldi Dantas de Oliveira; orientador, Walter Carlos Costa - Florianópolis, SC, 2015. 153.p Tese (doutorado) - Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Centro de Comunicação e Expressão. Programa de Pós- Graduação em Estudos da Tradução – PGET – Doutorado Interinstitucional em Estudos da Tradução – DINTER UFSC/UFPB/UFCG. Inclui referências I Costa, Walter Carlos. II. Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Estudos da Tradução. III. Título. Garibaldi Dantas de Oliveira O Outro E. M. Forster: uma tradução comentada de "The other boat" Tese para obtenção do título de Doutor em Estudos da Tradução Florianópolis _________________________________ Prof.ª Dr.ª Andréia Guerini Coordenadora do Curso de Pós-Graduação em Estudos daTradução (UFSC) Banca Examinadora ___________________________________________ Prof. Dr.Walter Carlos Costa Orientador (UFSC) -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Predicting Compensation and Reciprocity of Bids for Sexual And/ Or Romantic Escalation in Cross-Sex Friendships

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2009 Predicting Compensation And Reciprocity Of Bids For Sexual And/ or Romantic Escalation In Cross-sex Friendships Valerie Akbulut University of Central Florida Part of the Communication Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Akbulut, Valerie, "Predicting Compensation And Reciprocity Of Bids For Sexual And/or Romantic Escalation In Cross-sex Friendships" (2009). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 4159. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/4159 PREDICTING COMPENSATION AND RECIPROCITY OF BIDS FOR SEXUAL AND/OR ROMANTIC ESCALATION IN CROSS-SEX FRIENDSHIPS by VALERIE KAY AKBULUT B.S. Butler University, 2005 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Nicholson School of Communication in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2009 ©2009 Valerie K. Akbulut ii ABSTRACT With more opportunities available to men and women to interact, both professionally and personally (i.e., the workplace, educational setting, community), friendships with members of the opposite sex are becoming more common. Increasingly, researchers have noted that one facet that makes cross-sex friendships unique compared to other types of relationships (i.e. romantic love, same-sex friendships, familial relationships), is that there is the possibility and opportunity for a romantic or sexual relationship to manifest. -

A Qualitative Study of the Role of Friendship in Late Adolescent and Young Adult Heterosexual Romantic Relationships

A Qualitative Study of the Role of Friendship in Late Adolescent and Young Adult Heterosexual Romantic Relationships Billy Kidd Walden University, Minneapolis, Mn Magy Martin Walden University, Minneapolis, Mn Don Martina Youngstown State University, Youngstown, Ohio Abstract Friendship is considered one of the pillars of satisfying, long-term, romantic relationships and marriage. The purpose of this qualitative study was to examine the role of friendship in heterosexual romantic relationships. Eight single participants, ages 18 to 29, were selected from two West Coast metropolitan areas in the United States to explore whether or not friendship facilitates future long term relationships. Participants reported that friendship helped establish economic independence, adult identity and improved communication skills. Participants also reported that the development and stability of long term relationships was tenuous and temporal in their lives. Late adolescents and young adults in our study believed that their selection of partners was very different than their parents and that the success of their long term relationships was enhanced by a strong friendship with their partner. Keywords: friendship; adolescence; romantic relationships Certain psychosocial factors have been found to document that adult romantic affiliations are defined differently by the younger generation. There has been a sizable shift in sociocultural forces such as technological innovations, a globalized job market, constant mobility, shifting gender roles as well as the deinstitutionalization of marriage that influence late adolescent and young urban adult romantic relationships (Arnett, 2004, Coontz, 2006; Le Bourdais & Lapierre-Adamcyk, 2004). This process creates uncertainty in close relationships so that the traditional timelines and milestones for romantic relationships are seen as outdated (Collins & van Dulmen, 2006; Reitzle, 2007). -

Revlon Renews Spokesperson Contract for Academy Award Winning Actress Halle Berry; Global Beauty Leader Continues to Work with Hollywood's Most Recognizable Faces

Revlon Renews Spokesperson Contract for Academy Award Winning Actress Halle Berry; Global Beauty Leader Continues To Work With Hollywood's Most Recognizable Faces November 7, 2003 NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Nov. 7, 2003--One of the first cosmetics companies to feature a "spokesperson" in their advertising, Revlon, Inc. (NYSE: REV) today announced that it has renewed the contract for Academy Award(TM) winning actress Halle Berry(TM) to serve as a Company spokesperson. Berry recently completed a new advertising campaign for the Revlon Summer 2004 Color Collection. "Halle demonstrates our passion for beauty and plays a valuable role in reinforcing and building the Revlon brand image," said Stephanie Klein Peponis, Executive Vice President, Chief Marketing Officer, Revlon. "We are delighted that Halle will continue to be an important part of the Revlon brand." Revlon Team of Spokespeople Halle Berry is part of an accomplished group of confident, sexy, and multi-talented women who currently represent Revlon including two-time Academy Award(TM)-nominee Julianne Moore, Jaime King, Karen Duffy, and Eva Mendes. Both Berry and Moore recently shot print and television campaigns in New York for Revlon. About Revlon Revlon is a worldwide cosmetics, skin care, fragrance, and personal care products company. The Company's vision is to become the world's most dynamic leader in global beauty and skin care. Websites featuring current product and promotional information, as well as corporate investor relations information, can be reached at www.revlon.com, www.almay.com and www.revloninc.com. The Company's brands, which are sold worldwide, include Revlon(R), Almay(R), Ultima II(R), Charlie(R), Flex(R), and Mitchum(R). -

Fall Course Listing Here

FALL QUARTER 2021 COURSE OFFERINGS September 20–December 12 1 Visit the UCLA Extension’s UCLA Extension Course Delivery Website Options For additional course and certificate information, visit m Online uclaextension.edu. Course content is delivered through an online learning platform where you can engage with your instructor and classmates. There are no C Search required live meetings, but assignments are due regularly. Use the entire course number, title, Reg#, or keyword from the course listing to search for individual courses. Refer to the next column for g Hybrid Course a sample course number (A) and Reg# (D). Certificates and Courses are taught online and feature a blend of regularly scheduled Specializations can also be searched by title or keyword. class meetings held in real-time via Zoom and additional course con- tent that can be accessed any time through an online learning C Browse platform. Choose “Courses” from the main menu to browse all offerings. A Remote Instruction C View Schedule & Location Courses are taught online in real-time with regularly scheduled class From your selected course page, click “View Course Options” to see meetings held via Zoom. Course materials can be accessed any time offered sections and date, time, and location information. Click “See through an online learning platform. Details” for additional information about the course offering. Note: For additional information visit When Online, Remote Instruction, and/or Hybrid sections are available, uclaextension.edu/student-resources. click the individual tabs for the schedule and instructor information. v Classroom C Enroll Online Courses are taught in-person with regularly scheduled class meetings. -

Leading Female Characters: Breaking Gender Roles Through Broad City and Veep Abstract I. Introduction

82 — Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications, Vol. 11, No. 1 • Spring 2020 Leading Female Characters: Breaking Gender Roles Through Broad City and Veep Christina Mastrocola Cinema and Television Arts Elon University Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements in an undergraduate senior capstone course in communications Abstract Historically, television has been dominated by male leads, but feminism and the challenges faced by working women are becoming more prominent in recent programming.This study analyzed two comedy television shows with female lead characters, Broad City and Veep, to examine if their main characters break traditional gender roles. In addition, this research studied if Broad City portrayed more feminist values than Veep, using feminist theory, which examines obvious and subtle gender inequalities. Three episodes from each show were chosen, selected by a ranking website. The coder analyzed three subcategories: behavior, interpersonal relationships, and occupation. This study concluded that both Broad City and Veep depicted strong female lead characters who broke gender roles continuously through their behavior, relationships, and occupation. Broad City depicted more feminist values through their main characters’ friendship, empowerment of female sexuality, as well as their beliefs against traditional gender roles. This conclusion sheds light on the fact that women in television, especially female lead characters, do not have to be portrayed in a traditionally feminine way. I. Introduction Society has placed gender roles upon men and women, expecting everyone to conform. These roles derive from “traditional societal roles and power inequalities between men and women” (Prentice & Carranza, 2002, p.1). These stereotypes are often learned through observation, including portrayals in television, film, and other forms of media.